Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

Rabbinic conspiracies, Leviathan-riding heroines, a top-secret Israel Defense Forces demon-hunting unit, ghosts and amnesiacs, a gay messiah—all these can be found in the half-dozen books short-listed for this year’s Geffen Prize for best Israeli fantasy or science fiction novel, awarded in late September by the Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy.

It wasn’t so long ago that one could justifiably lament that fantasy literature was a weak strain in Israel, science fiction only somewhat less marginal, and that Hebrew literary culture was generally suspicious of the fantastical and speculative. (Ironic, since Zionism’s founder, Theodor Herzl, spun quite a yarn in his utopian novel Altneuland.) As novelist Hagar Yanai put it in a 2002 essay in Ha’aretz:

Faeries do not dance underneath our swaying palm trees, there are no fire-breathing dragons in the cave of Machpelah, and Harry Potter doesn’t live in Kfar Saba. But why? Why couldn’t Harry Potter have been written in Israel? Why is local fantasy literature so weak, so that it almost seems that a book like that couldn’t be published in the state of the Jews?

Since Yanai wrote these words, there has been something of an efflorescence of fantasy literature in the Hebrew language, and she herself is responsible for no small part of it. Her 2006 and 2008 novels, Ha-livyatan mi-bavel (The Leviathan of Babylon) and Ha-mayim she-bein ha-olamot (The Water Between the Worlds), comprise the first two installments of a promised fantasy trilogy (the conclusion seems to have gotten stalled), the first such in Hebrew literature, involving a couple of Israeli teenagers who travel from Tel Aviv to a magical version of the Babylonian Empire. As I wrote in my 2010 essay “Why There Is No Jewish Narnia,” those novels are not my cup of tea, but they were part of what I referred to at that time as “a very short shelf” of Israeli fantasy literature.

That shelf is no longer so short. The Geffen Prize is itself a gauge of the recent growth of fantastical writing in Israel. The prize was first awarded in 1999, but only for science fiction and fantasy novels translated into Hebrew and for short stories. Four years later, a prize category was created for original book-length works by Israeli authors and was awarded in alternating years until 2007, when Yanai’s Ha-livyatan mi-bavel received the prize. Since then, the award for an original Hebrew book-length work has been given each year. (The genres of science fiction and fantasy are combined for purposes of the award, just as in the case of the better-known Hugo and Nebula awards.) The prizes are announced at ICon, an annual convention in Tel Aviv that draws around 3,000 afficionados of fantasy, science fiction, and role-playing games.

A look at the six novels nominated for this year’s Geffen shows the current ferment and possibilities in the new Israeli science fiction and fantasy. These books reflect international trends in fantastic literature, especially the collapse of clear distinctions between fantasy, science fiction, and other genres. (Gary K. Wolfe, in his superb collection of essays on fantastic literature in England and America, calls these “evaporating genres,” and shows how the instability of these genres was built into their peculiar historical and commercial origins.) While some of these novels adhere to genre conventions, most draw promiscuously and in highly self-aware fashion from fantasy, science fiction, horror, detective fiction, and other genres. They also reflect the influence of film as much as literature, whether high or low.

What is most striking in considering this year’s crop of finalists, however, is how concerned they are with Judaism. Two of them, Ofir Touché Gafla’s Eshtonot (The Book of Disorder) and Yali Sobol’s Etsba’ot shel pesantran (Piano Fingers), are in different ways redolent of the Israeli scene, whether the actual Israel or a dystopian, near-future Israel, but do not deal with Judaism per se. Yet the other four, including this year’s winner, all make aspects of Jewish belief central to their fantasies. These books both confirm and challenge my speculations from a few years ago, which gave rise to considerable discussion and debate, and in which I claimed that normative Jewish theology, in contrast to Christianity, was not well-suited for dramatization in fantasy literature, or at least not in classic high fantasy.

More importantly, these books show that this new wave of Israeli science fiction and fantasy not only reflects global currents and popular culture, but also grapples with issues of Jewish belief and identity that continue to trouble and inspire Israelis, both religious and secular. These may not be Israeli Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

The only writer among this year’s finalists currently accessible in English is the wonderfully named Ofir Touché Gafla, whose delicious first novel, The World of the End, won the Geffen Prize in 2005 and was published this summer in an excellent English translation. The World of the End tells the story of Ben and Marian Mendelssohn, a married couple who seem to have the perfect relationship until Marian dies in a Ferris wheel accident. Although Ben works as an “epilogist,” a ghostwriter who specializes in devising endings for books and screenplays, he finds himself unable to accept the ending of Marian’s life and so follows her into the afterlife. In the course of Ben’s journey—which could be described as Orpheus and Eurydice meets Alice in Wonderland, with Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and Etgar Keret’s “Kneller’s Happy Campers” thrown in—he befriends a private investigator, visits a store where one can obtain videos of every moment of one’s previous life, drops in on deceased Jewish relatives, and learns about the “charlatans” (temporary residents of the afterlife, who will wake from their various comas and near-death states) and the “aliases” (denizens of the afterlife who never lived in the first place). The world beyond is filled with surprises, casting light and shadows not only upon Ben’s quest to locate his dead wife but upon what he thought he knew about their prior life together.

The book is a meditation on the deeply human need for, and defiance of, endings. Gafla probes the agonizing necessity, in grief over a beloved’s death or in the wake of a failed romance, of moving beyond the experience of finality in order to see life as continuing. He also shows, by contrast, that in love the dangerous temptation is to imagine that one has reached an ending and can live happily ever after, ignoring the ways in which all such endings are in some manner illusory. Gafla tells his story ingeniously, with a touch and timing as surely executed in the novel’s many moments of dark humor as in its moments of poignant heartache. The plot is at times overly intricate and defiantly improbable, with one too many secondary stories grafted onto the main trunk, but most every page is a dizzying delight. The novel should find as devoted a readership in America as it has in Israel.

Gafla’s latest novel and Geffen award nominee, Eshtonot (The Book of Disorder), also shuttles back and forth between the world of the living and other, more ambiguous states of existence. Creepy and complex, it draws together a series of uncanny threads. A man wakes up by the side of a road. He can’t remember anything except for his name, and on the back of his head is a small protrusion that feels like a switch. Another man is a prisoner in a placid and pastoral landscape surrounded by a wall. He and his fellow inhabitants are all murderers. Every night in a Parisian café, the romantic overtures of a breathtakingly handsome man are rebuffed by a homely woman. A boy fills notebooks with obsessively detailed lists of tragedies and disasters. What unites these strands is the novel’s fascination with epistemology: how we know that we know something, especially how we know whether or not we are real. Touché Gafla teaches writing at the Sam Spiegel Film and Television School in Jerusalem, and the twists and turns of the book recall various movies from the last decade or so that play upon this kind of uncertainty—Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Inception, The Sixth Sense, etc. Eshtonot is populated by a host of people severed from their memories, or from their pasts, or from the external world. While not as powerful as Gafla’s first novel, Eshtonot explores this panorama of dissociation with often spine-tingling results.

In contrast to the metaphysical chills provided by Gafla, Yali Sobol deals with political fears. If Israel ever becomes a fascist police state, don’t say that Sobol didn’t warn you. His slim dystopian novel, Etsba’ot shel pesantran (Piano Fingers), is set a few years from now in an Israel that has, in the wake of an elliptically described next war, implemented martial law and a tightening stranglehold on freedom of speech and expression. Like many a political fable about the danger of acquiescence to a repressive regime, the main character is an artist—here a classical concert pianist—who prefers to remain apolitical in an environment that will not allow such moral cowardice. (Sobol’s own musical background is rock—he was the lead singer of the band Monica Sex, which some American readers may recall for its infectious theme song to the 1990s hit Israeli television show Florentin—and he is the son of the playwright Yehoshua Sobol.) Sobol’s fable is directed against the Israeli right: Those persecuted by the government thought police are leftist poets, post-Zionists, kibbutzniks, and the like. The novel will therefore not resonate much beyond Ha’aretz readers, but it is deftly written and a grim barometer of the anxieties of the Israeli left.

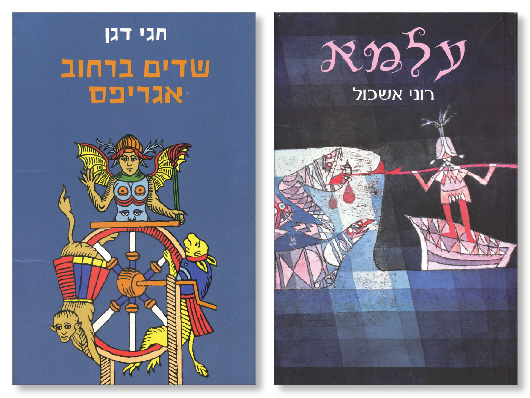

The winner of this year’s Geffen Prize is Hagai Dagan’s Shedim be-rachov Agripas (Demons in Agripas Street) about a group of paranormal investigators who work loosely with the IDF to manage unruly demons, sort of like an Israeli Ghostbusters or Men in Black. The protagonist is Shabi, a sex-obsessed slob of a Jerusalem cab driver who is made a member of the group after he evinces a mysterious talent for handling these supernatural beings. Shabi soon discovers that a cosmic crisis is at hand: a plot by a powerful group of evil angels to unleash permanently upon the universe the dark and violent side of God, what the kabbalists called Din (Judgment) as opposed to Chesed (Mercy). To triumph, these angels need to execute a group of imprisoned pagan deities, especially the Egyptian Isis and the Roman Fortuna, and so Shabi and his colleagues—a feminist academic, an ex-yeshiva student, a renegade physicist, and a Muslim Sudanese woman—find themselves in a race against time to save the goddesses and avert the end of days.

For his material, Dagan draws from his own 2003 Hebrew compendium of Jewish myths and countertraditions, Ha-mitologyah ha-yehudit (Jewish Mythology), and even quotes from it in Shedim be-rachov Agripas (Demons in Agripas Street), where it is presented, amusingly, as a passage from a demonic text known as “the Bible of Hell.” Dagan has given his readers an Israeli version of the kind of novel that, like Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, brings mere mortals in proximity to powerful ancient deities. Dagan likes playing these encounters for laughs, with an emphasis on slapstick and sex jokes.

Yet for all the humor that Dagan attempts to instill in the novel, there are very serious assertions, theological and political, being made. The battle between the evil angels and the pagan gods is just one of several ways Dagan, in this novel, attacks traditional Judaism. Judaism, the novel argues, banished the life-affirming feminine and natural dimensions found in paganism and so became sterile and oppressive. Rabbi Eliezer, the apparent loser of the famous talmudic “oven of Akhnai” story, in which he appeals successfully to God to support his interpretation of the law but is overruled by the other rabbis on a technicality, was in Dagan’s novel actually a valiant if unsuccessful hero trying to bring the Jewish and pagan deities together in a harmonious fusion. Eliezer wanted to unite the God of the Hebrews and the pagan goddesses in a sex-positive cult that would affirm femininity and the natural world rather than the stifling and patriarchal rigidity of Jewish law. One of his latter-day disciples expresses the need “to turn Judaism into something alive. Something connected to the world of those goddesses and gods who were here before God decided he wanted to rule alone.”

This is somewhat reminiscent of the Canaanite movement, a group of writers and artists who came onto the scene in the 1940s and argued that Israeli culture needed to shed its connections with Judaism and instead embrace a pre-biblical and pan-Middle Eastern culture of their imagination. Dagan’s closer ideological cousins, though, are the varieties of feminist spirituality that have, since the 1970s, attacked Judaism for supposedly inventing patriarchy and repressing the more feminine world of paganism—a view that often reprises Christianity’s early condemnation of Judaism as a dry and spirit-killing legalism, as well as its charge of deicide, in this case the elimination of goddesses rather than God.

Dagan’s religious critique is wedded to a palpable animus against ultra-Orthodox Jews and what many secular Israelis complain is the haredization of Jerusalem. The novel contains many venomous comments about haredi Jews (one of the characters asks semi-jokingly if they’re human), and, in case there were some ambiguity about Dagan’s feelings on the matter, he has the main evil angel disguise itself as an ultra-Orthodox rabbi who heads a yeshiva across the Green Line in the Arab neighborhood of Silwan. Moreover, while all the Orthodox Jews in the novel are sinister—or demons in disguise—all the Arab characters are kindly and well-intentioned despite their oppression by Orthodox Jews. The novel implies that if Judaism would open itself up to the pagan and feminine as Rabbi Eliezer had wanted it to do 2,000 years ago, there would be peace between Jews and Arabs today.

As if in response to comments I made in my Jewish Narnia essay about rabbinic Judaism’s deflation of the mythical element in Judaism, both Dagan’s Shedim ba-rachov Agripas and Roni Eshkol’s debut novel, Alma, feature warrior princesses riding on Leviathan, that primordial sea monster which God boasts of catching with a hook in the Book of Job, and which the rabbis of the Talmud claimed would provide a buffet dinner for the righteous in the world to come. While for Dagan this represents a hoped-for revenge of pagan, feminine myth against Judaism, Eshkol seeks a synthesis of Judaism and other thought systems, and her Leviathan is understood as part of a shattered unity that the characters in her quest fantasy seek to restore.

Alma is a young goatherd who lives in a squalid village in the land of Anlazya by the poisoned Northern Sea. When her curiosity leads her beyond the confines of her village, she encounters the Leviathan, whose frightening call wracks those who hear it with memories from their past. Alma discovers a map of the world on the skin shed from the Leviathan’s eye and uses it in a desperate war against a tyrant who has turned the southern hemisphere of the world into a hellish wasteland and now has designs on the north. Of the novels reviewed here, Alma is on the one hand the most bound up with the familiar conventions of fantasy literature. We have a young outsider who goes on a journey to save the world from a powerful evil and a mostly medieval technological level leavened by elements that seem magical.

On the other hand, Eshkol’s novel offers a unique and highly personal mythology, infused with Jewish elements both classical and modern. She gives her world a pungently ancient feel with Aramaic place names and Hebrew archaisms. The novel at times recalls Hasidic parables with their exiled kings and vanished princesses. There are festivals of remembrance that resemble the shofar service of the Jewish New Year. The Sauron of this world even bears the name of the devil in Jewish folklore, spelled backwards.

Modern Jewish experience is just as much an influence on the novel. The shattered south, with its tortured slave population and landscape of ash, filth, and skulls, is described in ways that go beyond Tolkien’s Mordor into the territory of Auschwitz. A Zionist sensibility animates the characters who rebel against the ancient dispersion of their tribe and seek to recover their homeland. “I cannot judge the decision of my forefathers” to go into exile, says one of the characters. “It was their choice and I respect it. But now the south is trampled while we enjoy the exile we took upon ourselves. As a son of the Wandering People I cannot return to the south,” he declares, “yet I can at least cease wandering.”

What most animates the novel is the theme of unity. The world of Alma is a sundered world, which the protagonists seek to reunite. Alma and her companions are deeply concerned with the nature of unity, of God (“the One”), and the question of how there can be evil and strife, or desire, or sexual duality in a creation that is supposed to be whole. These explorations are syncretic: partly Jewish and partly inspired by eastern sources (the main fount of wisdom in the novel is a being named Satoria—satori is a Zen term for enlightenment). Eshkol fails to create compellingly vivid correlations to these explorations in her characters and narrative action; one feels that Alma and her companions would be truer to their principles if they just sat on mountaintops and meditated instead of riding around doing things, and their quest feels accordingly arbitrary. Yet the broken world through which they move has genuine atmosphere.

In contrast to the fantastical realms of Alma, Ilan Sheinfeld’s Kesheha-meitim hazru (When the Dead Returned) is, for the most part, decidedly this-worldly. The first half of the novel is a sprawling family epic drawn from Sheinfeld’s own family history, and reminiscent of the novels of Isaac Bashevis and Israel Joshua Singer. It begins in the Bessarabian shtetl of Novoselic in the years leading up to the Holocaust and moves from Eastern Europe to the jungles of the Amazon as members of the family immigrate to South America. Apart from a few brief magical realist touches there is nothing supernatural in the book’s first half, although Sheinfeld’s realistic recounting of the family’s experience of the Holocaust—a universe of horror, a world of walking corpses—seems as much like science fiction or horror as any work of fantastical literature.

The theme of messianism is foreshadowed from the start. Early on, a mysterious stranger shows up in the village and gives one of the characters a Seder plate decorated with symbols of Shabbtai Zevi, while another character heads off to Palestine to purchase land in the Galilee near the reputed grave of Moses’ daughter, who figures prominently in Sabbatean myth. The family patriarch, a furrier named Shlomo Feldman, is infused with messianic yearning, though a bitter foe of the Sabbatean sympathizers he runs across.

The second half of the book focuses on Salomon Feldman, the grandson of Shlomo and the son of Michael, Shlomo’s son who is separated from the family early on when he is struck in the head and loses his memory, spending the war years in the home of a Christian farmer. After the war, Michael makes his way to South America and settles in Iquitos, a town in the Amazonian rainforest that is home to a large number of Jews who have intermarried for generations with the local Indian population. (This may also seem somewhat fantastical but is the typically improbable reality of Jewish history.) Michael marries an Indian woman who claims to be partly of Jewish descent and who dies after giving birth to Salomon. Salomon grows up, attends university in Lima, becomes a historian, and wrestles with his homosexuality. Through his searches for the key to his own identity he makes his way to Israel.

In the final third of Sheinfeld’s book, Salomon is revealed as the messiah, probably the first gay messiah in a novel since Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. When Salomon, as yet unaware of his redemptive powers, begins inadvertently to raise the dead, it is the occasion for macabre Jewish comedy, as the extended Feldman family descends upon the sleepy little town in Northern Israel in which Salomon resides. It turns out that having one’s deceased aunts, uncles, and cousins resurrected also means the resurrection of family feuds and pettiness.

As more and more dead Jews are brought to life, Sheinfeld spins out a clever and audacious social comedy dealing with the Zionist project itself: how the State of Israel has, metaphorically speaking, accomplished the messianic feat of bringing wildly different Jews and Judaisms back to life under one national roof and is dealing with the consequences. Can medieval and modern Judaisms coexist? Who gets to decide, “Who is a Jew?” Are the formerly dead eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return?

Ultimately, the novel is about Salomon’s attempt to reconcile his sexual identity as a gay man with his religious and national identity as a Jew. Unfortunately, this is also where the novel fails, as Salomon circles around and around the same struggles to come out of the closet, never finding a resolution, but never advancing the novel either. Losing control of the satirical elements, the novel turns shrill and repetitive. The rabbis from the ancient Sanhedrin return to life and organize mass killings of gays, there is civil war in Israel, and Salomon is cruising in Tel Aviv bars and complaining about his family. It could be argued that Sheinfeld’s novel does not really belong in the category of science fiction or fantasy. Not because there is little that is fantastical in the first two-thirds of the novel, and not because the supernatural elements in the novel are drawn directly from Jewish tradition (if given a gay, modern Israeli spin) and do not stand on their own imaginatively, but rather because the messianic fantasy here is mainly an allegory of the author’s own search for identity, a family record, and a personal confession, rather than the construction of a counterreality that carries its own aesthetic weight.

Finally, we come to Shimon Adaf’s Arim shel mata (De Urbibus Inferis). Poet, critic, editor, rock musician, novelist, Shimon Adaf has already gained considerable recognition for his brilliant writing, winning Israel’s prestigious Sapir Prize for his last novel and various prizes for his collections of poetry. His current novel is part detective novel, part science fiction, part Bildungsroman, part philosophical reflection on language, and certainly the most challenging and unsummarizable of the books here at hand.

The novel deals with the siblings Tiveria and Akko Asido, who, like the Sderot-born Adaf, are of Moroccan background, and who spend their childhood in the shadow of their father, a recluse who hides in a shack researching Jewish mysticism. Tiveria (she and her brother are named after the Israeli cities of Tiberias and Acre) eventually moves to Tel Aviv, studies classics, and becomes a poet, while Akko, a mathematical genius, heads to MIT and works on artificial intelligence. The third main character in the novel is the narrator, who encounters a mysterious symbol carved into the frame of a mirror in a Berlin club, which leads him to uncover a secret organization, hinted at in various rare editions of Jewish mystical texts. Like Dagan does in Shedim ba-rachov Agripas, Adaf also traces his underground organization to the esoteric teachings of a 2nd-century Jewish sage. In this case, it is Shimon ben Zoma, of whom the Talmud records that he went insane when he entered the divine garden which caused Rabbi Elisha ben Abuya to renounce Judaism and from which only Rabbi Akiva returned spiritually and physically unharmed.

Rich material—with arson and amnesia and angels, as well—yet this novel, while engrossing and beautifully written, isn’t driven by a plot in any conventional sense. The narrator’s investigations bring him into contact with the Asido siblings, but the characters remain mostly separate from one another, and the knowledge they acquire in the course of the novel does not ultimately change much in their lives. What unites and propels disparate strands of the novel is instead a concern with language itself. Adaf, through the different incarnations of language dealt with in the book—poetry, mathematics, scripture, computer code, gravestones, Moroccan dialect, tattoos, Christian iconography, instant messaging, music—gestures yearningly at the horizon of language, seeking, as does Jewish mysticism, to find words for what is beyond words. This might sound like a recipe for post-modern navel-gazing, but Adaf is so lyrically gifted and so humanly focused on the characters that the novel never threatens to become an academic exercise.

What for Adaf lies most achingly beyond his own ample poetic abilities is his bottomless grief over the death of his sister Aviva, which he has grappled with in earlier books. Arim shel mata is ultimately a work of mourning, in a sense akin to what Walter Benjamin, one of Adaf’s tutelary spirits, meant by the German term for tragedy, Trauerspiel. “I will not finish, I think, the work of mourning,” we read at the novel’s end. “But perhaps with the conclusion of this book I will be able to stop writing it.”

That Adaf has found science fiction and fantasy to be such responsive vehicles for his philosophical and personal searches (his previous novels are also major contributions to fantastical literature in Israel) is indication of the talent these genres are attracting in Israel and the attention Israeli contributions to these genres should and will merit, with the help of translators, in years to come.

Meanwhile, more and more classic and contemporary fantasy and science fiction is making its way into Hebrew. For instance, Adaf recently translated Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, an alternate history in which the Axis powers win the Second World War, while this year’s Geffen award for best translation of a work of fantasy went to Tzafrir Grossman’s Hebrew rendering of A Dance with Dragons, the fifth novel in George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones series.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Challah Moment

America is having a challah moment that coincides with two food movements in popular culture.

A Cipher and His Songs

Avraham Halfi faced outward, a gifted comic performer, and inward, a lyric poet of resonant privacy.

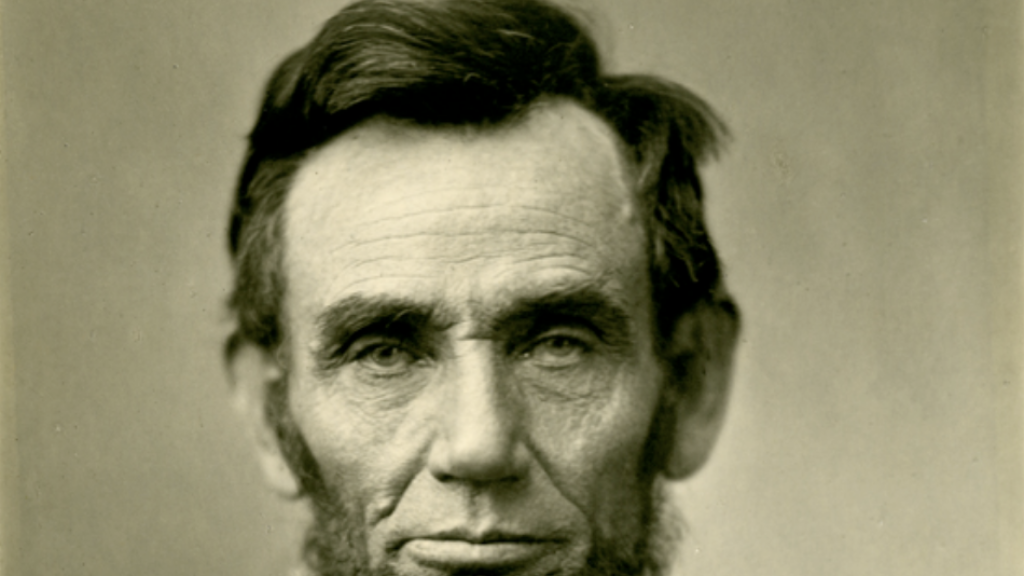

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

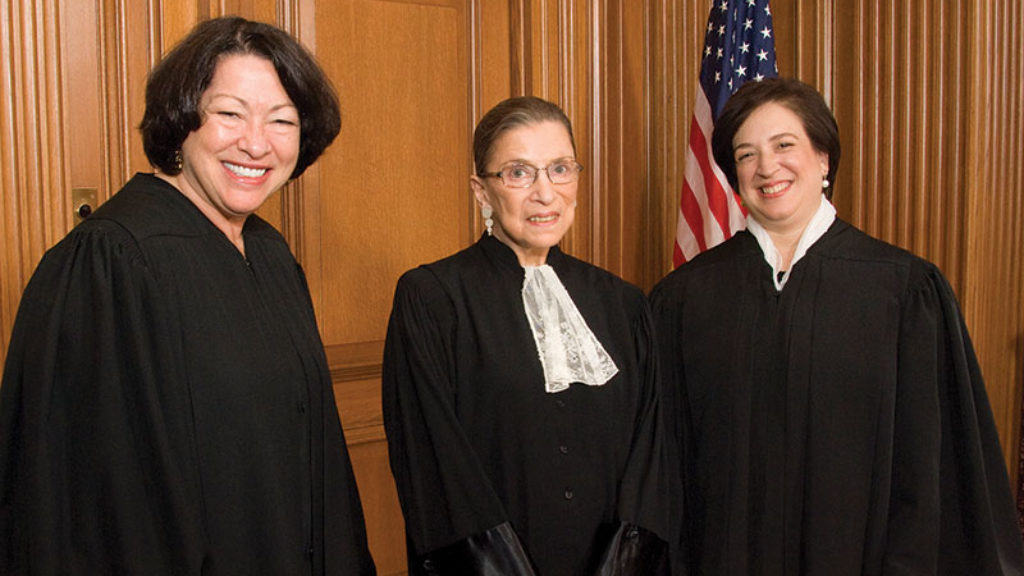

Great Jews in Robes

If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court.

bkissileff

Enjoyed this piece! For English readers, Shimon Adaf's novel Sunburnt Faces is now available in English translation.