A Life of Dialogue

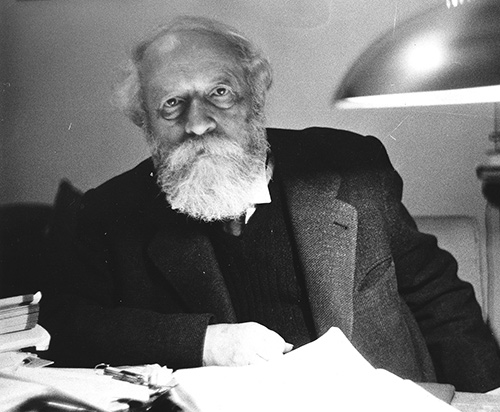

Gershom Schocken, the longtime editor of the Israeli daily Ha’aretz, once recalled taking a walk with the great Hebrew novelist Shmuel Yosef Agnon, during which they discussed the many controversies in Israel surrounding Martin Buber. “Agnon abruptly stopped, looked, and said: I would like to tell you something. There are people about whom you must decide whether you love or hate them. I decided to love Buber.”

Paul Mendes-Flohr’s new biography of Buber, the first to appear in English in more than 30 years, is not exactly an act of love, but it is the culmination of an ardent, lifelong preoccupation with the philosopher, extending from his 1972 doctoral dissertation to his current work as editor in chief of the 22-volume German edition of Buber’s collected works. Deftly setting Buber’s philosophical and theological writings within the context of both European and German Jewish intellectual and cultural life in the early 20th century, Mendes-Flohr’s book is an excellent general introduction to the life and thought of one of the 20th century’s most important thinkers. It also documents Buber’s concern with the spiritual and ethical character of the Zionist movement and, following its establishment, of the State of Israel. This led him to become, in Mendes-Flohr’s words, “a self-conscious outsider in the context of pre- and post-1948 Zionism.”

Born in Vienna in 1878, Buber suffered a terrible blow three years later when his mother left him and his father to elope with a Russian officer. She left without saying goodbye. Soon after, his father sent him to live with his own parents in Lemberg, in Galicia (modern-day Lviv, Ukraine). His grandfather Solomon Buber was a wealthy philanthropist and independent scholar of the “science of Judaism,” known for his scholarly editions of classic collections of midrash; his grandmother Adele was an autodidact who took charge of the young Buber’s education and instilled in him a love for languages. Buber became fluent in seven of them—including German, Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish, and English—and learned to read several more. He also received a traditional Jewish education, studying classical sources and rabbinic literature with his grandfather and great-uncle, a prominent Talmud scholar. What the young Buber didn’t receive was anything that could even begin to alleviate what he later described as the “infinite sense of deprivation and loss” with which his mother’s desertion had left him. Indeed, Mendes-Flohr, following Buber himself, attributes much of his lifelong effort to probe the depths of the interpersonal dimension of human life to his childhood experience of abandonment.

At age 14, Buber left his grandparents’ home and the largely traditional world in which he had been raised to live with his father, who had remarried. As an adolescent, Buber gravitated, like so many of his contemporaries, toward the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. In fact, Buber was so taken with Thus Spoke Zarathustra that he resolved to render it into Polish—abandoning the project only after learning that a prominent Polish poet had already started to translate it. Buber’s early writings are shot through with Nietzschean motifs and language, exalting “the will to power and the rebirth of the instinctual life,” in defiance of modern rationalism. Buber remained at heart, Mendes-Flohr writes, “an Apostle of Zarathustra,” even though he would distance himself from Nietzsche’s teachings later in life.

Buber went on to study philosophy, literature, and art history at the universities of Vienna, Leipzig, Zurich, and Berlin. His two most important teachers were Wilhelm Dilthey, best known for his distinction between the methods of the natural and human sciences as well as the two kinds of knowledge they produced, and Georg Simmel, one of the founders, together with Max Weber, of the new field of sociology. Like many other contemporary intellectuals, Buber became disenchanted with what he considered the hollow intellectualism of modern thought and sought redeeming value in mystical traditions. Liberated from the illusion of multiplicity and the constraints of time and space, Buber wrote, the mystic comes to experience “the unity of the self with the world.”

Buber had by this time shed any concern with Judaism and could be accurately described by one of his cousins as someone who demonstrated a “typical Jewish anti-Semitism.” What brought him back—not to his religion but to his people—was Zionism. In 1899, he founded a chapter of the Zionist Jewish Students Association in Leipzig. He was motivated not by political concerns but, following the cultural Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginsberg), by a commitment to Jewish spiritual and cultural rebirth. For Buber, Mendes-Flohr writes, “Zionism was, first and foremost, a spiritual fulcrum by which to overcome the personal—indeed, existential—condition of the modern Jew.”

Theodor Herzl, impressed by the 23-year-old Buber’s charisma and eloquence, appointed him in 1901 to serve as editor in chief of Die Welt, the official organ of the World Zionist Organization.But after only four months, Buber abruptly broke with Herzl and resigned from his editorship, apparently over tensions between what he considered the misguided political goals of the mainstream Zionist movement and the cultural Zionism of the “Democratic Faction,” to which he belonged.

Buber gradually withdrew from Zionist activity, ceasing to be involved in the movement altogether by 1905. Although he would remain committed to the cause of Jewish cultural and national renewal for the rest of his life, he would do so from the margins.

Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their liberal-Jewish inheritance with a vision of Judaism they could identify with. Adopting his teacher Georg Simmel’s dichotomy between “religion” and “religiosity,” he juxtaposed what he regarded as the sterile rationalism and rigid prescriptions of traditional Judaism (religion) with its primal spiritual forces (religiosity). As David Biale notes in his biography of Gershom Scholem, under Nietzsche’s influence Buber “emphasized the importance of myth over rationalism in Jewish history” and found Judaism’s creative impulses in “subterranean, even heretical movements.” Buber characterized Jewish history as a perpetual struggle between the conservative elements of “official Judaism” and the spiritual forces of “underground Judaism.”

Buber, who first encountered Hasidim in his youth in Galicia but hadn’t been attracted to their beliefs, now found in the mystical movement the greatest expression of Judaism’s creative spiritual energy. In opposition to rationalists like the historian Heinrich Graetz, who described Hasidism as “the wildest superstition,” Buber described it as a wellspring of spiritual dynamism and an ideal organic community. Buber’s turn to Hasidism, Mendes-Flohr notes, was also motivated “by a desire to counter the negative views of eastern European Jewry.” Buber’s writings on Hasidism, especially his early books—The Tales of Rabbi Nachman (1906) and The Legend of the Baal Shem (1908)—were celebrated widely by Jews and non-Jews alike. Even the prominent scholar of Jewish mysticism Gershom Scholem, who would later famously criticize Buber’s portrayals of Hasidism, acknowledged the profound significance of Buber’s early collections of Hasidic tales for his generation of German-speaking Jews.

In his important three addresses on Judaism delivered between 1909 and 1911 and published in 1916 to the Bar Kokhba Zionist circle in Prague, Buber called on young German Jews to make the renewal of the Jewish people their “personal task.” For the renewal of Judaism will only occur, Buber argued, “when Judaism’s spiritual process, which is a process of religious struggle and religious creativity, is restored to life, in word and deed, by a generation earnestly resolved to translate its ideas into reality.” In 1916, he founded the journal Der Jude (The Jew), which became during its existence one of the most influential intellectual forums for German Jewry, publishing Franz Kafka, Arnold Zweig, Walter Benjamin, and Eduard Bernstein, among others.

Like many intellectuals of his generation, Buber was briefly swept up in the patriotic war fervor that spread across Germany during the First World War. Despite his initial attempts together with a group of intellectuals from across Europe to prevent the imminent conflict in the summer of 1914, Buber celebrated the advent of war enthusiastically. Employing Ferdinand Tönnies’s famous distinction between Gesellschaft (society) and Gemeinschaft (community), he asserted that the experience of the war would bring about a new, more authentic Gemeinschaft. He imagined that young Jewish soldiers, as a result of their experiences in the trenches, would be more “seriously” and “responsibly” attached to their Jewishness than ever before. Amid the chaos and destruction of total war, Buber glimpsed an unmistakable revelation of something momentous: the rebirth of a new Jewry.

Gustav Landauer, Buber’s closest friend and an uncompromising opponent of the war, decried the “profound confusion and bewilderment” of Buber’s wartime politics. Denouncing what he labeled the Kriegsbuber (the war Buber), Landauer found it “utterly scandalous” that his friend could see in the war’s carnage and destruction the “spirit of genuine community.” Landauer found particularly abhorrent Buber’s claim that Jewish soldiers had enlisted en masse not out of a sense of compulsion but in order to fulfill some paramount, cosmic mission.

Landauer’s harsh rebuke provoked, according to Mendes-Flohr, “a radical transformation in Buber’s thinking.” Buber moved away from the mystical and heroic voluntarism of his youthful writings and toward the philosophy of dialogue for which he would earn great renown. In subsequent years, political and social issues, absent from his youthful writings, would become central to his thought.

In the years following World War I, Landauer’s unique brand of mystical and communitarian anarchism would serve as the foundation for Buber’s political thought, “especially regarding the salience of interpersonal relations in shaping spiritual and communal life.” Buber first outlined his political ideas in a speech in 1918 that he later dedicated to Landauer, who had been brutally beaten to death during the Bavarian Revolution in May 1919. Along with several prominent Protestant theologians, Buber played a central role in founding the religious-socialism movement. At the same time, he developed his own version of cultural and humanitarian nationalism, which was focused on guarding Zionism against the moral and spiritual degeneration of modern European nationalism. “I don’t know anything of a ‘Jewish state with cannons, flags, and military decorations,’” he wrote to Stefan Zweig.

Buber became a key figure in the Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus, a school of Jewish adult education founded by the young philosopher-educator Franz Rosenzweig in Frankfurt in 1920. It attracted many of the leading Jewish intellectuals of the time. The two philosophers were “drawn to one another by a compelling intellectual and spiritual affinity,” Mendes-Flohr writes. In 1922, Rosenzweig was diagnosed with ALS and was soon confined to a small attic apartment, where Buber would visit him regularly. Although by then Rosenzweig could only write with the help of his wife, Edith, and a specially constructed typewriter, in 1925, the two men began work on their monumental translation of the Hebrew Bible into German. Buber would continue the translation project alone following Rosenzweig’s death in 1929, completing it in 1961.

Buber’s 1923 classic Ich und Du (I and Thou) famously begins by declaring that “The world is twofold for man in accordance with his twofold attitude.” The book would earn him worldwide recognition. In it, he distinguished between two fundamental modes of relating to the world. There is the “I-It” mode by which one relates oneself to one’s surroundings—including other human beings—as objects of use or experience. By contrast, there is the “I-Thou” mode, in which “one does not experience, but meets, the Other” in an unmediated relation of true reciprocity and recognition. Following the publication of I and Thou, Mendes-Flohr writes, Buber devoted his life to elaborating the thesis that “true life is realized in the I-Thou encounter.”

We might say that Buber’s was a philosophy not of existence but of coexistence. Like no thinker before him, he highlighted the way that relationships and dialogical interactions between human beings not only give meaning and purpose to our lives—they are constitutive of life itself. Human beings, Buber taught, are shaped by and through their relationships with others, without whom their lives would be meaningless, empty affairs.

This philosophy of dialogue must also be viewed as an attempt to overcome the epistemological starting point of modern philosophy, which, ever since Descartes, had grounded reason in the reflexive, self-given certainty of the isolated thinking subject. Buber rejected the ideas that human beings were simply free-floating minds and that Cartesian doubt of everything but one’s own thinking was possible. The “life of dialogue,” he insisted, is a fundamental orientation toward the world as a place in which human beings are, at every moment, addressed—by others, by the world, by God, whom Buber called “The Eternal Thou”—and given the opportunity to respond out of the fullness of their beings. Buber’s major contribution to philosophy was to insist that the human social world of relationships was the primordial ground of philosophical inquiry.

The most important “Thou” of Buber’s life, both intellectually and personally, was for six decades Paula Winkler. She was a Bavarian Catholic by birth but was as religiously unaffiliated as Buber himself by the time they met in a seminar in German literature at the University of Zurich during the fall semester of 1899. She had a “bohemian, exotic flair” and had recently been “the only beautiful woman” (at least according to the philosopher Theodor Lessing) in a mystical colony in south Tyrol led by a Jewish-born Muslim sage named Omar al-Raschid Bey. They fell in love and had two children before they were married. Buber initially concealed all of this from his grandparents for, as Mendes-Flohr puts it, in an obvious understatement, “knowing that Martin had two children out of wedlock with a non-Jewish woman would surely have confirmed his grandparents’ fears that secular studies would lead him astray.” Only in 1907, after his grandfather had passed away, Paula had converted to Judaism, and the couple had gotten married, did Buber let his grandmother in on the secret. For the next 50 years, Martin and Paula shared not only a romantic bond but an intellectual partnership. An accomplished writer and author herself, Paula took an active role in her husband’s work. She was, Mendes-Flohr writes, “Buber’s most trusted critic and intellectual collaborator.”

Buber remained in Germany for as long as he could after Hitler’s rise to power, organizing “spiritual resistance” against the Nazis. He left Germany just in time, in 1938, moving to Jerusalem, where he would spend the rest of his life as a professor of social philosophy at the Hebrew University. Buber never managed to fully master spoken Hebrew, and his friends often joked that, as Mendes-Flohr writes, “his elementary Hebrew would allow his audience finally to understand what he had to say.”

Buber was an outsider in the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine. He staunchly opposed the Zionist movement’s pursuit of national and territorial sovereignty, fearing that it would inevitably lead to a violent conflict with Palestine’s Arab population. Even before he moved to Palestine, Buber had been active, together with other leadingJewish intellectuals associated with the Brit Shalom (covenant of peace), a movement to establish a binationalstate in Palestine for both Jews and Arabs. He continued to advocate for binationalism on both moral and political grounds even after the Holocaust. In November 1946, he defied the official Zionist leadership by appearing independently before the Anglo-American Inquiry Committee to present a program for a binational state. In his testimony before the committee, Buber declared that the Zionist project “must not be gained at the expense of another’s independence.”

Nevertheless, Buber’s political radicalism was tempered by the constraints of reality. “I have accepted as mine the State of Israel,” he declared after the state’s establishment in May 1948. “I have nothing in common with those Jews who imagine that they may contest the factual shape which Jewish independence has taken.” Instead, he insisted that henceforth the “command to serve the spirit is to be fulfilled by us in this state.” He took his cue from the prophets of Israel for whom, Buber wrote, “compromise with the status quo is inconceivable,” but who made no attempt to “escape from it into the realm of a contemplative life.” Even so, Buber was fully prepared to remain, as Mendes-Flohr puts it, “a self-conscious outsider” in the fledgling state. He continued to protest Israel’s policies toward Palestinian Arabs who lived within its borders and to voice his concerns for the ethical character of the country. His status as a dissenter reached its peak with his opposition to the trial and subsequent execution of Adolf Eichmann—a stance for which he was widely criticized. But at the age of 84, Mendes-Flohr writes, “Buber had long reconciled himself not to belong.” Nevertheless, when he died in 1965, thousands attended his funeral services at the Hebrew University. Among the mourners were not only Gershom Schocken and S. Y. Agnon but Israel’s prime minister, Levi Eshkol, who delivered one of the eulogies, and its president, Zalman Shazar, who was a pallbearer.

Suggested Reading

The Home Front

Eating very long breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with dozens of aging members of the Greatest Generation was the best part of Arkush's teaching experience.

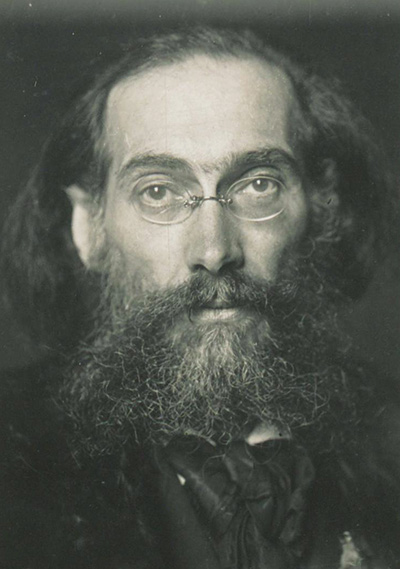

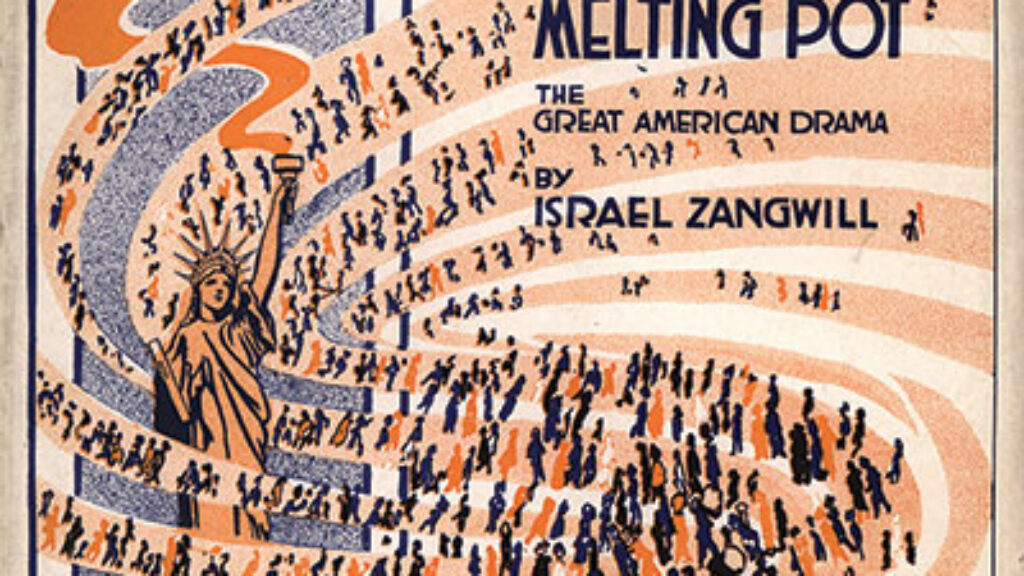

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

Black Money

Terrorism is not cheap. Find a way of taking terrorists’ money, the logic would seem to dictate, and you may have a way of shutting them down.

State or Substate?

“Nonstatist” Zionists, as the historian David Myers has dubbed them, have received a lot of attention in recent years. Dmitry Shumsky, a historian at the Hebrew University, is grateful for this scholarship but believes that it has not gone far enough.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In