Forget Remembering

Carrot or knife? Anti-Semite or Jewish grandmother? Graveyard or lovers’ lane? Rutu Modan’s new graphic novel, The Property, is a tale of seemingly irreconcilable oppositions. As in her first graphic novel, Exit Wounds, Modan’s theme is the uneasy coexistence of love and death.

At first, the story seems simple: A grandmother, Regina, and her adult granddaughter, Mica, travel from Israel to Poland to reclaim a family apartment. The book’s structure seems to echo this apparent simplicity, with each of the seven chapters covering one day of the trip. However, Regina’s motives in returning to Poland are far more complex than she has led Mica to believe.

One of the joys of this novel is the gradual and open-ended revelation of character. When we first meet Regina, she is insisting—to Mica’s embarrassment—that she be allowed to take a giant water bottle past a security checkpoint at the airport. She continues far beyond the point by which most people would have given up—insisting on questionable “rights” (to drink her water, to block the line), questioning airport regulations (“Were they handed down to Moses at Mount Sinai?”), offering the security guard a sip, and playing the trump card of guilt: “I’m an old woman! Do you want me to get dehydrated?”

“A piece of work,” I wrote in the margins, and a breakfast scene in the third chapter seems to validate that impression. Regina insists she was unable to sleep the night before, because Mica stayed out all night. “You were fast asleep when I came in . . . ” Mica points out, and Regina has a ready answer: “I hold everything in. From the outside you can’t tell how hard it is for me.”

Regina is probably exaggerating about the sleep. But, as one realizes over the course of the book, she is telling the truth about herself. She left Poland as a young woman in 1939, fleeing personal difficulties; her parents, sister, and brothers stayed. Regina “lost everything,” as Mica later realizes; and most of the time, she tries not to let these losses show.

More minor characters are equally nuanced. Avram, a cantor with designs on Regina’s property, spends much of the novel lurking and lying. Yet, as we discover, he has his reasons, which stem from love as well as greed. In one of the final scenes, in an attempt to convince Mica of his latest lie, he begins singing the Jewish funeral prayer for victims of the Holocaust. It is a sublime moment, his song swelling and filling the page. (The moment is soon interrupted by the appearance of an outraged Regina, who begins hitting him, and then by a bystander, who accuses Regina of anti-Semitism.)

This is not to say that, as we get to know the characters, we discover that they are all good at heart. Our sympathies wax and wane; our judgments waver. Towards the book’s end we see a sympathetic Polish character, who helped Regina’s family during the war, make an offhandedly anti-Semitic remark. Modan’s characters are as self-contradictory as real people.

The story is full of miscommunications, machinations, shifting allegiances, and dissonant truths. Characters want to control others’ perceptions, but don’t realize their own perceptions may be distorted. “You shouldn’t have let a stranger see me like this,” Regina tells Mica, after Mica’s new Polish boyfriend has nursed Regina through a difficult night; but is the man who fed her soup really a stranger?

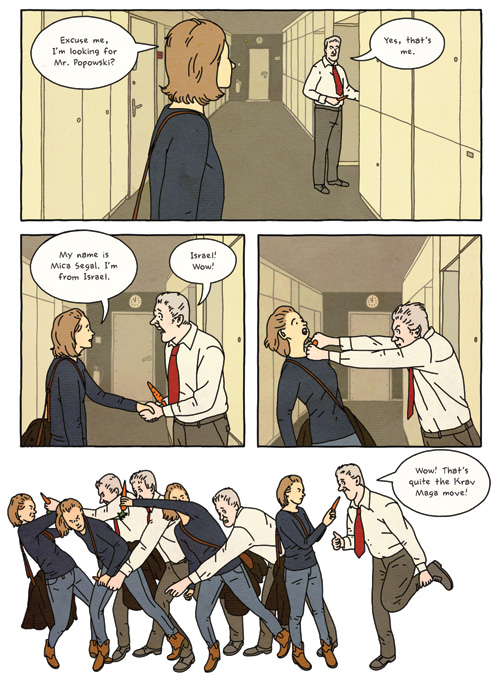

Illustrations depict emotions that go unnoticed and actions at odds with characters’ words. Regina, whaling away at Avram in the climactic scene, shouts pieties about mother-love. Sometimes, illustrations play with readers’ expectations, as in a silent fight sequence during which an accountant, having learned that Mica is Israeli, threatens her with a lunchtime carrot. “Martial arts are my life,” he explains afterward, grateful for the impromptu Krav Maga demonstration.

Modan makes full use of the graphic medium. Backgrounds appear and disappear, depending upon how much the characters are noticing. During a moment of deep recognition, the faces of two lovers fill their frames: All they see is one another. Sometimes, by simply following a minor character past the ending of a scene (a switch in perspectives that is much easier to accomplish here than in traditional novels), the novel shows the disparity between public words and private thoughts. Textual elements become part of the story: A speech bubble spills over with words as an overwhelmed Mica spills over with tears; comic-book exclamations (“SLAM,” “BANG BANG”) underline a scene’s emotional violence.

A graphic novel about the Holocaust almost inevitably invites comparisons to Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Maus II. The Maus books famously allegorize humans as animals; but, in all other ways, the images provide straightforward illustrations of a Holocaust testimonial. Image and text work together to convince readers of the truth of horrifying events, even as the substitution of animals for humans provides a slight distancing effect. In Modan’s novel, text and illustrations disagree almost as often as the characters.

Perhaps that is because the focus of The Property is not on the Holocaust, but on how, even after such knowledge, we live now. The novel depicts our modern, calloused world, in which a stranger on an airplane requests a seatmate’s dinner roll and Holocaust testimony in almost the same breath, in which a tour of concentration camps is a common rite of passage for Jewish teenagers, in which re-enactments of round-ups are a part of Warsaw street culture. Alongside all this busy remembrance, there is a strain of Jewish thought, memorably depicted in Philip Roth’s The Counterlife, that contrasts the “graveyards” of Europe with Israel’s “theater of Jewish life.” Gratitude for Israel and immersion in the Jewish present and future are meant to eclipse memories of the traumatic past: “FORGET REMEMBERING!” Characteristically, Roth portrayed the extreme version of this perspective via an attempted airplane hijacking by a New Jersey kid named Jimmy, who probably could have used a girlfriend.

In The Property, the character of Regina embodies the dueling impulses to remember and to forget. Some writing about post-war Israel described the conflicting perspectives of European refugees, who found it a matter of deepest urgency to remember the Shoah, and “sabras,” who believed themselves to be living in the bright Jewish future. One of this novel’s major themes is the inadequacy of such simple oppositions: Regina, who arrived just before the war began, is refugee and sabra both, and neither.

It is deeply discomfiting to live with that kind of ambivalence, and Regina has spent most of her life trying to bury the past. In the first chapter, she scornfully rejects the idea of a “roots journey”: “I couldn’t care less about Warsaw. It’s one big cemetery.” And yet, there she is, on a plane to Poland, talking with obvious pride (and some exaggeration) about her distinguished European ancestors. She tries to live according to rigid rules about whom to trust (not Poles), but finds trustworthy and deceitful people everywhere. Modan explores Regina’s journey towards some kind of reconciliation with admirable empathy, reserve, and humility.

This novel departs from easy oppositions, recognizing their coexistence, if not in logic, then in life. Israel is the place where Regina and Mica live, and the place where Mica’s father, Regina’s son, has recently died: a theater of life and a graveyard. Poland is the place where Regina’s family was murdered and where she first fell in love. A graveyard can also be “a wonderful place” for lovers to meet. No place, and perhaps no person, either, can be just one thing—or, for that matter, another.

On her last night in Warsaw, Regina says, “It still hurts as much. But now it’s mixed up with other things.” Mica listens from within a yellow pillar of hallway light, which partially illuminates the murky room. It is worth it, this novel suggests, to find out about those other things, and there is a measure of relief in accepting complex and contradictory truths.

The novel closes with Regina and Mica on a homebound flight. They complain about the airplane rolls, then eat them anyway. Regina suggests Sweden as a rendezvous point for Mica and her Polish beau. (A holiday fling, or something deeper?) She knows that country well, having traveled through it when escaping Poland. As a young woman, Regina feared Sweden’s sunless winters. Now, she tells Mica what her husband told her in 1939: “They say Sweden in the summertime is the most beautiful place in the world.” It gives away nothing to say that this is where this marvelous book ends: on a wordless, lush summer landscape of flowers and greenery, with vast, bare, icy mountains in the background.

Suggested Reading

The Old Country, Twice Removed

My grandfather had a way of mentioning the Kiev guberniya (province) that made it sound to me, when I was a boy, like it was our place in the Old Country—and more than half a century later, it still does.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

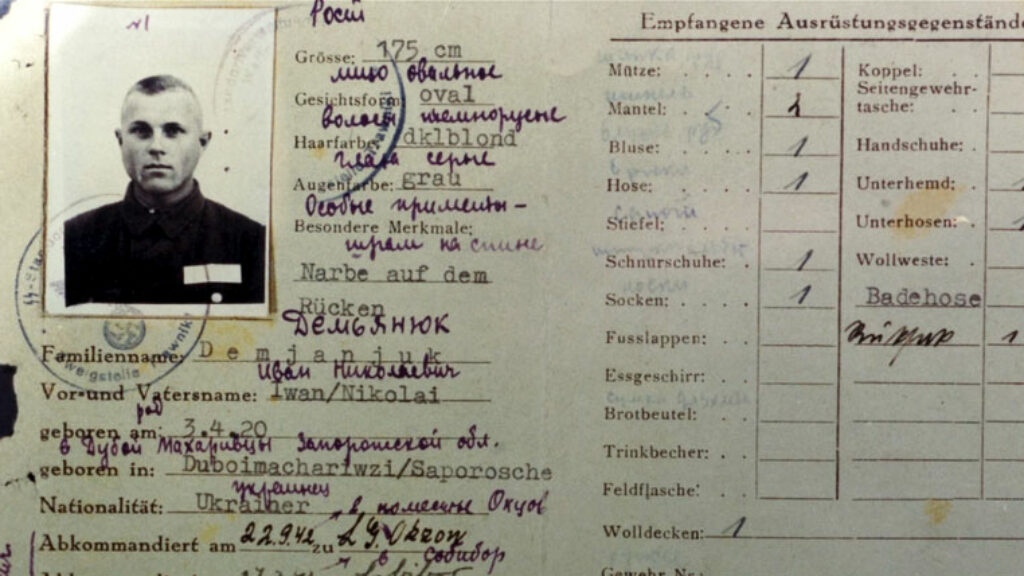

Ivan the Terrible?

A new miniseries from Netflix manages to maintain the tension of the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case of John Demjanjuk.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In