Exodus and Egyptology

The commentators of the new, lavishly illustrated Susan and Roger Hertog edition of Exodus in The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel show how understanding ancient Egypt illuminates the Israelite exodus—and our seders.

The Plague and the Egyptian Frog Goddess

Frogs played a special role in ancient Egyptian religious thought. Amulets shaped like frogs dating back to prehistoric times were discovered in Egypt, and the frog goddess Heqet, one of the earliest goddesses in the ancient Egyptian pantheon, was associated with fertility and birth, probably because of the large number of eggs laid by frogs in apparently effortless deliveries. In an ancient Egyptian mythological scene, Heqet helps the ram god Khnum to create human beings on a potter’s wheel and accompanies him as he leads the pregnant queen Ahmose to her divine delivery room.

Since ancient Egyptians believed in resurrection, they included motifs of birth and delivery in their burial sites. They equipped tombs with amulets and artistic elements, including frog amulets, related to birth and delivery.

Scholars have also suggested that frogs may have been associated with life after death because of a surprising natural phenomenon: Certain bodies of water in ancient Egypt, such as artificial lakes, dried up during the summer. These lakes generally held large populations of frogs that disappeared in the summer months and returned when the lakes refilled. Ancient Egyptians, who conceived of this phenomenon as an expression of overcoming death, associated the frog goddess Heqet with life after death. Interestingly, the hieroglyphic sign of Heqet, a frog, was used in writing the title Wehem Ankh meaning “repeating life”—a title used in tomb inscriptions to express hope for an afterlife.

The fact that Heqet was depicted as a frog did not mean that all frogs were identified with her. Frogs were part of ancient Egyptian fauna. Like everything in ancient Egypt, nature had to abide by the rules of Maat, the deification of the cosmic order. The king’s responsibility for maintaining the rules of Maat was one of the most important aspects of his role as monarch.

Through the plague of frogs, God was establishing His dominance over the ancient Egyptians’ gods as well as over their king. By disturbing the natural order, God showed that He is master over every aspect of the world that the ancient Egyptian gods—and the king—were believed to control.

The Plague of Darkness

The plague of darkness is depicted in the Torah as the one that nearly cracked Pharaoh’s stubbornness. But why? From a modern perspective, it is hard to understand why this plague is described as being so severe. After all, no Egyptian was killed or even injured by the darkness. What made it so dreadful?

The plague of darkness is an excellent example of how an understanding of the Torah is enhanced by exploring and understanding the beliefs of ancient Egypt. A reading of this story is entirely different, for example, with the knowledge that the sun was always the most dominant element in the Egyptian sky.

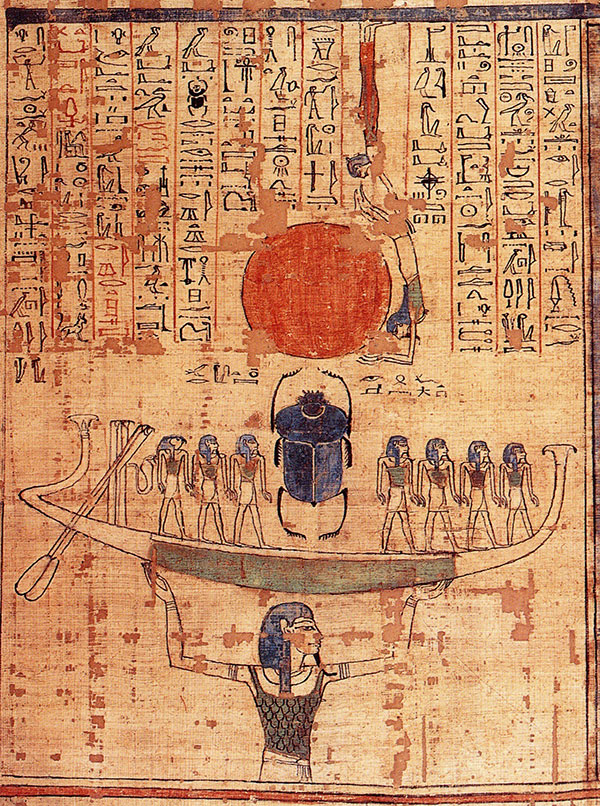

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, the sun god was considered the head of the pantheon. According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, he is the creator god whose initiatives and will enabled him to create himself in the primordial waters as a male being with female elements. He gave birth to the first pair of twin gods, male and female, the first pair to be sexually differentiated – and thus completed the passage from pre-creation to creation. Subsequently, the sun god was believed to sustain his presence in the world through the sun disk. His creative power was retained as the light emanating from his rays.

The ancient Egyptians understood creation as an act of differentiation, naming, and definition. Because light allows the distinction of one thing from another, they considered light to be the creative power that maintains the world.

The sun god was believed to have a solar barque, or boat, and an entourage with which he crossed the sky every day from east to west. He would start his cruise in the eastern horizon as a new-born baby, become a man at his prime at noon, and an old man in the evening. When the sun god set in the western horizon as a tired old man, he entered the Realm of the Dead, the Netherworld, in his solar barque, beginning his dangerous nocturnal sail.

Every night, the sun god fought his way through the Netherworld to be reborn again in the morning. In the Netherworld, the giant chaos serpent Apophis would try to stop him, to prevent the sun god’s rebirth. Each night, the sun god and his entourage managed to fetter Apophis and cross the Netherworld successfully, and consequently guaranteed the continuous existence of the world.

Ancient Egyptian society was very anxious about the possibility that the sun god might fail his nocturnal sail in the Realm of the Dead, and never rise again. It was believed that this would allow chaos to take over creation and bring the world to its pre-creation state of endless dark, inert, and opaque waters. Hence, the solar priests of ancient Egypt performed detailed nightly rituals to secure the sun god’s journey.

It is against the ancient Egyptian fear of chaos that one must read the biblical text about the plague of darkness. In the eyes of the ancient Egyptians, the fact that the sun did not rise meant that the sun god failed to cross the Netherworld, and chaos prevailed.

This was certainly one of the most frightening and disturbing thoughts an ancient Egyptian could have – and, therefore, preventing the rise of the sun god in the morning was probably the best way to show off the might of God.

The Literary Style of the Song of the Sea

Ashira, “I will sing” —the opening word of the Song of the Sea—is identical to what is found in triumphal poems in the royal archives of Ugarit in Syria. Other literary elements of the Song of the Sea—one of the great epic poems of the Tanakh—are parallel to what is found in neighboring Western Semitic and Egyptian myths and inscriptions.

The Song of the Sea bears a striking resemblance to Western Semitic myths about one of the great gods vanquishing a sea deity and thus securing eternal lordship—a concept referred to here in the Song of the Sea’s final verse. God, the “Warrior,” rises up as master of the waves and unleashes His fury against His foes.

According to Bar Ilan professor Joshua Berman, the most striking parallel to the Song of the Sea is the Egyptian account of Ramesses II’s victory over the Hittite empire at the battle of Kadesh. Ramesses inscribed an account of this battle on monuments across his empire. There are ten copies of this work, known as the Kadesh Inscription, that have survived.

The Kadesh Inscription is remarkably similar to the account of the battle against the Egyptians. Ramesses’ troops break ranks at the sight of the Hittite chariot force. Ramesses pleads for divine help and is encouraged to move forward with victory assured. Ramesses’ troops return to survey the enemy corpses. They offer a victory hymn that includes praises of his name, references his strong arm, and gives tribute to him as the source of their strength and salvation. Ramesses is described as consuming his enemy “like chaff” —and he leads his troops peacefully home, intimidating foreign lands along the way. He arrives at the palace and is granted eternal rule.

That there are so many parallels between the Kadesh Inscription and the Song of the Sea is another example of the Torah’s adaptation of the form and plot line of ancient Near Eastern literature to tell its own story of salvation. Ancient Near Eastern victory poems, especially the Ramesses poem, give glory to the conquering king who, with the help of the gods or as a divine being himself, smites and defeats the enemy. In the Song of the Sea, there is no human involvement—God himself single-handedly defeats the Egyptian army.

Suggested Reading

Pour Out Your Fury

When the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of books from monasteries in 1803, among them was an utterly unique haggadah.

Law in the Desert

Studying the weekly portion with Jerome, Nachmanides, and others, the seemingly tedious parts of Exodus become compelling.

Let My People Go

Many of the heroes of the Soviet Jewry movement have been unsung, until now.

The Kid from the Haggadah

A 1944 poem, translated by Dan Ben-Amos.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In