At the Threshold of Forgiveness: A Study of Law and Narrative in the Talmud

Near the end of tractate Yoma, the Mishnah limits the scope of the Day of Atonement:

For sins between man and God, Yom Kippur atones. But for sins between a man and his fellow, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases his fellow.

In a sense, the injured party becomes the master of his injurer’s future, for only his pardon can make atonement possible. R. Elazar ben Azariah is quoted as having derived this principle from a biblical verse that describes the purifying force of the Temple service on Yom Kippur: “For on this day atonement shall be made for you to cleanse you of all your sins; you shall be cleansed before the Lord.” (Leviticus 16:30)

In its plain sense, the phrase “before the Lord” simply refers to a place, the Temple, where atonement occurs. It probably also indicates that it is God who grants this atonement. But R. Elazar ben Azariah treats “before the Lord” as a restrictive clause, understanding it to mean that only sins against God—those that are “before the Lord”—are atoned for by Yom Kippur. Atonement for transgressions committed against other people depends not on God but on reconciliation with the injured party.

The Talmud develops this requirement for human forgiveness into a full-fledged legal institution. First, the request for forgiveness must be public: “R. Chisda said that he must placate his fellow before three lines of three people.” This is, again, tied to the creative reading of a biblical verse, but the clear intent is to make the request for forgiveness a social fact. A single, casual encounter involving only the injurer and the injured will not suffice. The next talmudic statement ensures that, on the other hand, the injurer does not become a permanent hostage to the injured party: “R. Yosi bar Chanina said, ‘whoever seeks forgiveness from his friend should not seek it more than three times.'”

The Talmud then emphasizes the centrality of the moral community to this process of effecting atonement for an offense against someone who has died:

And if [the injured person] has died, [the injurer] brings ten people, and has them stand next to his grave; he then says, “I have sinned against the Lord, God of Israel, and against so-and-so, whom I injured.”

Here, the community serves as a substitute for the injured party, but there must also be the sense of a real encounter.

There are ethical and religious systems in which an encounter, public or otherwise, between the injurer and the injured party is not central to the idea of forgiveness. The Stoic, for instance, grants forgiveness as an expression of autonomy, foregoing what is properly due him. The point is not to restore a relationship but rather to free oneself from one, since the toxic force of a grudge might harm his inner life. In contrast, one who forgives as an act of Christian grace is concerned with the injurer’s soul, ideally extending forgiveness in advance of any expressed remorse. The absence of any necessary encounter between injurer and injured makes these models of forgiveness quite different from the one formulated by the Talmud.

The juxtaposition of law and narrative is a characteristic and important feature of the Talmud. After discussing the formal requirements for requesting forgiveness, the Talmud presents four brief stories of encounters in which rabbinic masters attempt to reconcile with those they have injured. Each of the stories raises the question of the power and limits of the law to structure such a complex human moment. I will focus on the first three of these stories, setting them down, as did the editors of the Talmud, one after another.

R. Jeremiah injured R. Abba. R. Jeremiah went and sat at R. Abba’s doorstep. When R. Abba’s maidservant poured out wastewater, some drops sprayed on R. Jeremiah’s head. He said, “they have made me into a trash heap,” and he recited, the verse “[God] lifts up the needy from the trash heap,” (Psalms 113:7) as being about himself. R. Abba heard him and went out to him. He said to him, “Now it is I who must appease you, as it is said, ‘Go abase yourself; and importune your fellow’ (Proverbs 6:3).”

When a certain person injured R. Zera, he would repeatedly pass before him and invite himself into his presence, so that the injurer would come and appease him.

A certain butcher injured Rav, and he did not come before him [to seek forgiveness]. On the day before Yom Kippur, [Rav] said, “I will go and appease him.” R. Huna met him. He asked, “Where is my master going?” He said, “To appease so-and-so.” [R. Huna] said [to himself] “Abba [i.e. Rav] is going to kill a man!” Rav went and stood over him. The butcher was seated, cleaning the head [of an animal]. He raised his eyes and saw him [Rav]. He said to him, “Abba, go; I have nothing to do with you.” While he was still cleaning the animal’s head, a bone shot out, struck the butcher’s neck, and killed him.

A simple historical observation will help us to see the issues that the editors of the Talmud were exploring in these anecdotes: Rav lived before R. Zera. The ordering of these stories is not chronological; it’s conceptual.

In the first incident, R. Jeremiah, who has come to ask forgiveness from R. Abba, is seated at the threshold, probably finding it difficult to enter, fearing that R. Abba will rebuff him, or worse, that his appearance will renew the injury. The humiliation he suffers at the hands of the maidservant suddenly reverses the situation; now, having been sprayed with dirty water, he is R. Abba’s victim. His ironic recitation of the verse brought R. Abba out to ask his pardon, and the threshold (literal and figurative) was crossed.

The story seems intended to point out a serious problem with institutionalizing the requirement that forgiveness be requested. One can formulate rules that dictate how to ask for forgiveness, but these rules can only come into play when an encounter between the injurer and injured is possible. This requires a kind of preliminary appeasement. The narrative thus demonstrates the limitations of the law as it appears before us. One might say it places the law itself at the threshold. Every request for forgiveness is preceded by some forgiveness that makes the request possible. But how does the Talmud deal with the forgiveness that must precede forgiveness?

The next story, which follows immediately after that of R. Jeremiah, suggests an answer to this question. R. Zera used to indirectly invite himself into the presence of one who had injured him, providing an occasion for the injurer to reconcile with him. His action, which is presented as worthy of emulation, creates the conditions in which it will be possible for the injurer to approach him. The injured party extends the forgiveness that precedes forgiveness without any assurance that the injurer will in fact be remorseful and request his pardon. But this act of grace does not obviate the remorse that must precede full reconciliation; it only makes it possible. Nor is it, apparently, legally required. The passage presents us with an exemplary story that expresses the greatness of grace without making it a binding norm.

The third story shows why R. Zera’s practice was an act of pure grace that cannot be turned into law. The story tells of Rav, who, on the eve of Yom Kippur, was awaiting the arrival of the butcher who had injured him. When the butcher does not come, Rav decides to go to him. At first blush, Rav’s action seems quite similar to R. Zera’s. Knowing that Yom Kippur will not expiate the butcher’s sin unless he appeases his fellow, Rav decides to waive his honor and go to the butcher himself. In fact, he does more than cross the threshold from the injured party’s side to that of the injurer; he also crosses class lines. There is a vast class divide between Rav, the leading scholar of his generation, and the lowly butcher. Moreover, the timing of the story—the eve of Yom Kippur, the last minute for doing what needs to be done to make atonement possible—marks a threshold in time.

The reader’s first impression of Rav’s action as a model of generosity is undermined by the reaction of R. Huna, Rav’s greatest student. Instead of seeing the initiative as an act of great generosity, R. Huna sees it as an act of violence. He says to himself that his master is going to kill the butcher, and events bear him out. This fact compels us to see that the key to interpreting this subtle little story lies in the reaction of R. Huna, who understood exactly what was going to happen.

Perhaps Rav had been waiting all day for the butcher to come to him. Perhaps he had been waiting all year. On the eve of Yom Kippur, the affront remains intense, but the hour grows late, and he decides to go to him. Something about Rav’s demeanor or his pace or the very hour, coupled with the disparity in status between Rav and the butcher, suggested to Rav Huna that this was an act of aggression.

The story of Rav and the butcher forces us to confront the ambivalence between sanctity and narcissism that inheres in any act of grace. Rav’s appearance before the butcher turns out to be quite different from R. Zera’s sensitive and indirect approach. Instead of giving the slaughterer an opportunity to request forgiveness, Rav backed him into a corner and brought about a terrifying opportunity for reciprocal injury. Knowing of Rav’s closeness to God, R. Huna knew where this could lead, though he was apparently incapable or unwilling to stop him. The combination of Rav’s aggressiveness and Rav Huna’s apparent passivity sealed the fate of the stubborn butcher who was not inspired to repent by the appearance of the eminent man in the doorway of his shop.

Jewish law and narrative have been joined since the Bible, and one can identify three paradigms for the relationship between them. The first and simplest is when the narrative provides a basis for the law. The story of the exodus from Egypt, for example, explains the meaning of the paschal sacrifice and the various rules of the seder. The second paradigm emphasizes the way in which the story permits a transition to a different sort of legal knowledge. A story allows us to see how the law must be followed; we move from “knowing that” to “knowing how.” More than a few talmudic stories play that role, showing that it is sometimes no simple matter to move from text to action. The third paradigm is the most delicate. Here, the story actually has a subversive role, pointing out the law’s substantive limitations. That is the paradigm for our series of stories of encounter and forgiveness.

The first story, as noted, shows the way in which there has to be a partial reconciliation before the full reconciliation, a forgiveness before the forgiveness. As a result of that limitation, the second story suggests a secondary, even saintly, norm, in which the injured person makes an effort to enable the crossing of the threshold by insinuating himself into the presence of the injurer. The third story then shows that solution to be limited, since the outcome of the intrusion could be a further injury. It may not be as drastic or seemingly supernatural as the butcher’s tragic end, but a request for forgiveness can turn into a further insult all too easily.

The Talmud pointedly does not go on to formulate further legislation to resolve this issue. Would it be possible to use a further norm to structure the question of how to make the first step? Can one mark with any degree of generality the distinction between a delicate or indirect meeting and an accusatory intrusion? The law as a process of generalized rulemaking here reaches its limit. Requesting forgiveness ultimately requires tact, sound judgment, and a profound and precise analysis of one’s own motives.

In Moses Maimonides’ great medieval codification of the laws of repentance in the Mishneh Torah, the rules of requesting forgiveness are further formalized, while the stories of R. Jeremiah, R. Abba, R. Zera, Rav, R. Huna, and the butcher are left aside. Separating law and narrative in that way removes a layer of meaning, and flattens our understanding of the process of reconciliation. The Talmud’s frequent joining of the two genres embodies a profound expression of humility, for the law thereby acknowledges its own limits. This is especially true in the case of forgiveness, which is a part of the complex and delicate fabric of interpersonal relationships.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Seeds of Subversion

The "Other" Jewish tradition.

Brotherhood

How did the world's most antisemitic play become a symbol of positive Christian-Jewish relations? Karma Ben Johanan's new book explores an evolving dynamic.

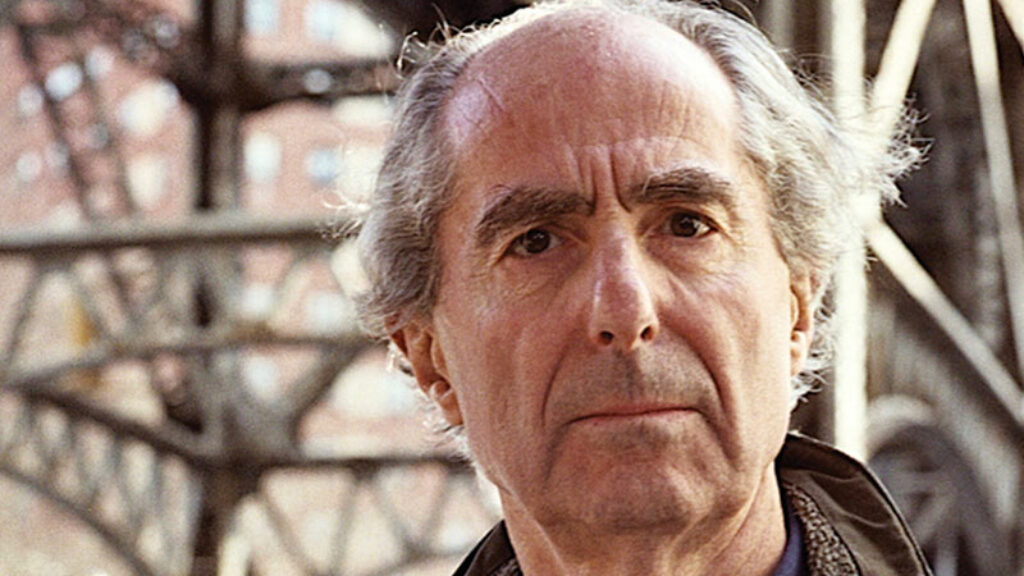

Not a Nice Boy

To every author who seemed too cautious—which was nearly every author he knew—Roth gave the same advice. “You are not a nice boy,” he told the British playwright David Hare. His friend Benjamin Taylor’s memoir is . . . nice.

Intrigues and Tzuris

Have you seen the one about the Hasidic jewelers and the Albanian goons?

gwhepner

WHY DEATH’S ANGEL KILLED THE HAD GADYA’S BUTCHER

Steps you take to be forgiven may produce

awarenenesss in Death’s Angel’s office

of the offender’s wrong and terminate the truce

between him and Malakh HaMoves.

That’s why the butcher died when Rav

demanded righting of a wrong,

and why Death Angel chose to carve

the butcher in the seder night’s last song.

[email protected]