Letters, Summer 2014

Reform Revisionist

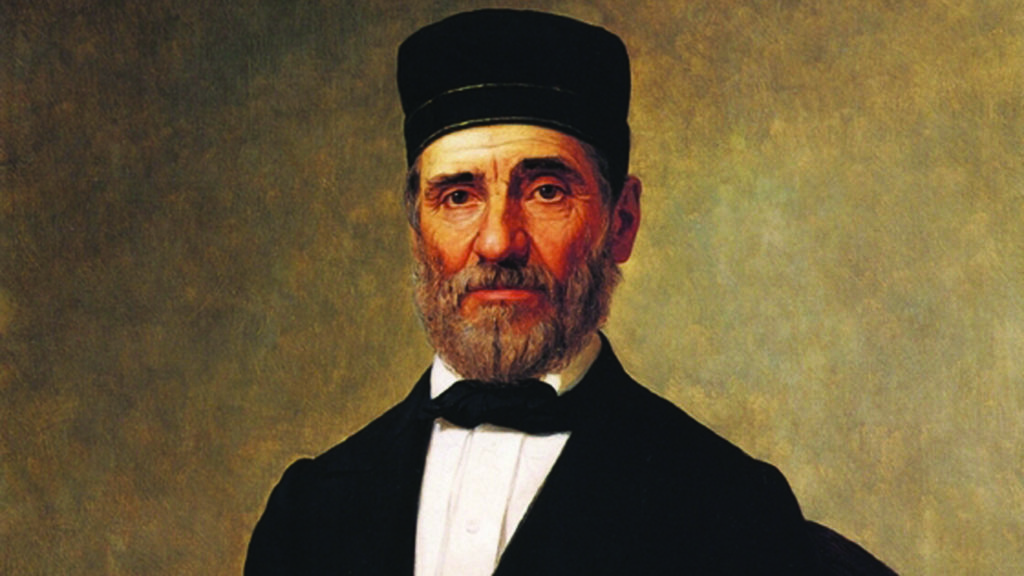

Although I enjoyed Stuart Schoffman’s article (“A Stone for His Slingshot,” April 2014), I would like to take issue with Schoffman’s word choice in referring to my grandfather, Rabbi Dr. Louis I. Newman, as an “erstwhile antagonist” of Ben Hecht. I assume this refers to my grandfather’s justifiable condemnation of Hecht’s 1931 book, A Jew in Love. A reader might come away with the impression that Newman and Hecht bore a long-term antagonism toward each other that was only resolved toward the end of Hecht’s life. Nothing could be further from the truth.

After 1939, Hecht and Newman shared a common passion. As Schoffman’s article indicates, Hecht’s views changed dramatically in 1939. Rabbi Newman was always an ardent and proud promoter of the Jewish religion, Jewish culture, the Jewish people, and Zionism. When much of the Reform Jewish leadership in the United States was anti-Zionist or barely Zionist, Rabbi Newman was a Revisionist. He used to meet with both Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin when they were in New York. He raised money for Irgun missions to save Jews from Europe and transport them to Palestine until such missions became impossible. For a number of years, my grandfather’s home on Central Park West was Jabotinsky’s mailing address in New York City. Rabbi Newman was an ardent supporter of the Bergson Group, and he worked closely with Yitzhaq Ben-Ami, one of the leaders of the group. In fact, my grandfather was an attendee at the November 1948 banquet for Menachem Begin, where, as the article mentions, Ben Hecht gave a short speech. It was quite appropriate that Rabbi Newman officiated at Ben Hecht’s funeral.

Saul Newman

via email

Rashi‘s Shul

Ivan Marcus’ enlightening review of Rashi by Avraham Grossman (“Our Master, May He Live,” Spring 2014) is illustrated by an old photograph of Rashi’s synagogue in Worms. The caption reads “built in 1034, destroyed in 1938.” That is not incorrect, but could well leave the impression that the synagogue no longer exists. On the foundation walls, using, as far as possible, original stones and the restored portal and apse, the synagogue was reconstructed in the late 1950s. If one were to google “Worms synagogue,” among the first photographs that should appear are recent ones taken from a similar angle as the one in your photograph. Strictly speaking, the synagogue destroyed in 1938 and rebuilt after the war is not identical to the one built in 1034. That one was destroyed during the first and second crusades and rebuilt on the same site in 1174.

The greater tragedy, of course, was the annihilation of Worms’ Jewish community. The reconstruction of the synagogue was not uncontroversial, as few if any Jews returned to Worms immediately after the war. Today, between 32 and 300 Jews live in Worms, depending on who is counting. Most are immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their young descendants.

Herman Reichenbach

Hamburg, Germany

Khazars Shmazars

I would like to comment on Stampfer’s review (“Are We All Khazars Now?” Spring 2014). Elhaik, who misuses me as a source in his article, makes a number of wrong assumptions (in italics) that call for further comment.

The Khazar Empire already existed in the late Iron Age in the central-northern Caucasus: The first time the Khazars appear in the literature, is in ca. 670 when they moved on their way south into the region of the Middle Volga, the region of the Samara river, about one thousand kilometers north of the Caucasus (Zuckerman 2007, 425). The aforementioned date is far past the late Iron Age, which means that the Khazars cannot have had an empire in the Caucasus in the late Iron Age.

The Khazars converted to Judaism in the 8th century: King Bulan of the Khazars converted to Judaism in 861 (Zuckerman 1995). It is unknown how many Khazars joined in the conversion. Therefore, even apart from the wrong period, there is no evidence for Elhaik’s assumption that the Khazars converted in any century.

Caucasus Georgians and Armenians are considered as proto-Khazars: Considering Georgians and Armenians as proto-Khazars is not based on genetic research, is not so formulated by the authors referred to, and is not in agreement with reliable information about Khazars.

Prior to their exodus, the Judeo-Khazar population was estimated to be half a million in size: As it is unknown how many Khazars converted to Judaism, and no reliable censuses exist in Eastern Europe before 1897, the estimate of half a million Jewish Khazars has no factual basis.

Because, according to both [the Khazar and Rhineland] hypotheses, Eastern European Jews arrived in Eastern Europe roughly at the same time (13th and 15th centuries): The 13th century appears to refer to the collapse of the Khazar Empire. Elhaik seems to be unaware of the Jewish presence in the region of the Black Sea already from the beginning of the Common Era (e.g., Harkavy 1867, 77-97; Dan’shin 1996). There are no sources that show that these Jews disappeared up to the 13th century.

The 15th century refers to the expulsions of Jews from the bigger cities, which according to Elhaik amounted to 50,000 Jews. During these expulsions, the Jews left the bigger cities and settled in villages (Germania Judaica III). Moreover, the number of 50,000 has no factual basis and would have left virtually no Jew in Germany, while the expulsions continued during the 16th century.

In addition to the above, Costa et al. (2013) concluded that “There is no evidence in the mtDNA pool to support the contention that lineages might have been recruited on a large scale from the North Caucasus […] as would be predicted by the Khazar hypothesis.” Therefore, the historical and demographic mistakes by Elhaik together with the conclusion by Costa et al. refute any important genetic link between (East) European Jews and Khazars.

As to the “demographic puzzle” mentioned by Stampfer: The number of 50,000 Jews in 1500 leading to more than eight million in the 20th century, is no puzzle. The number of 50,000 (DellaPergola 2001, 22) is a modification of the numbers 30,000 and 10,000 originally proposed by Baron (1957, v.16, 4) and Weinryb (1972, 32), respectively. These numbers were not based on factual evidence, but on the assumption by the last two authors that these Jews had arrived in Eastern Europe following mass migrations from Germany during the Middle Ages. Because there weren’t that many Jews in Germany in that period, the number had to be low. The validity of the mass migrations and the low numbers is considered as Torah mi-Sinai, despite the fact that there is no evidence for the mass migrations. In an earlier publication Stampfer (2012, 134) mentions a Jewish growth rate of only (my italics) 1.7 percent between 1500 and 1700 also starting out from 50,000 Jews in 1500. In the current article, Stampfer explains this number by comparing the high Jewish growth rates with the ones of the French who migrated to Canada (or of the Dutch who migrated to South Africa). This explanation does not hold for two reasons.

First, the author seems to be unaware of the fact that one cannot use the growth rate of population A in ecosystem X and assume that this same growth rate can also be applied to population B in ecosystem Y when the two ecosystems are completely different.

Second, annual growth rates of 1 percent or more did not occur in Europe before 1800. Nevertheless, historians and geneticists who deal with the origin of East European Jewry accept the high growth rates, and now we are stuck with the problem of how to defend a demographically impossible growth rate.

A number of arguments were proposed to explain these growth rates, such as low age at marriage, low infant mortality, higher rates of divorce, and better hygiene. However, no comparative research was ever carried out, because there are no (reliable) data in Eastern Europe during this period to carry out such research. Based on realistic growth rates, the number of Jews in Eastern Europe (say, the area of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) in 1500 must have been about half a million or more (van Straten 2007).

Jits van Straten

Bennekom, the Netherlands

Shaul Stampfer Responds:

I thank Jits van Straten for his comments. The discussion continues in my review of his book, The Origin of Ashkenazi Jewry: The Controversy Unraveled, in the most recent issue of East European Jewish Affairs.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Taking Responsibility: A Rejoinder

Between rabbinic rulings and public policy: a response from Daniel Goldman and Yossi Shain and a rejoinder from Yehoshua Pfeffer.

The Golem of Montreal

The famous golem of Prague was invented by a forger, faith healer, amulet salesman–and the most enterprising kosher chicken slaughterhouse supervisor of Montreal.

Watching Game of Thrones, Waiting for Shavuot

Binge-watching the traditionless Game of Thrones while looking forward to the traditional binge-learning of Shavuot.

Minhag America

Since the founding of the United States, the American "synagoguge" has survived as a flexible institution—some would argue, too flexible.

pollack

How may we humble readers gain access to the many references to books and articles in Jits van Straten's helpful letter above?