Brief Kvetches: Notes to a 19th-Century Miracle Worker

A young man falls into despair because running his tavern has left him less and less time for Torah studies. A husband is distraught because his wife, who is the family’s sole provider, has become possessed by a demon that recently flung her down into the mud and forced her to stab herself. A miller who was cursed by a Gentile shepherd claims that he feels his legs weaken day by day. A widow’s only son has been drafted into the tsarist army, where she fears he will be permanently lost to the Jewish people.

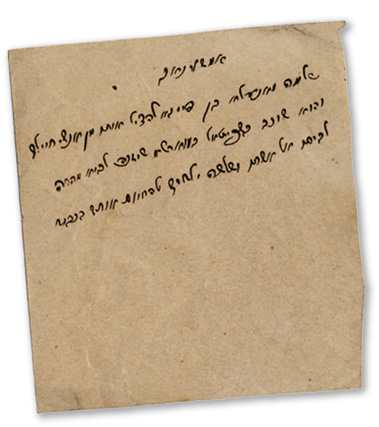

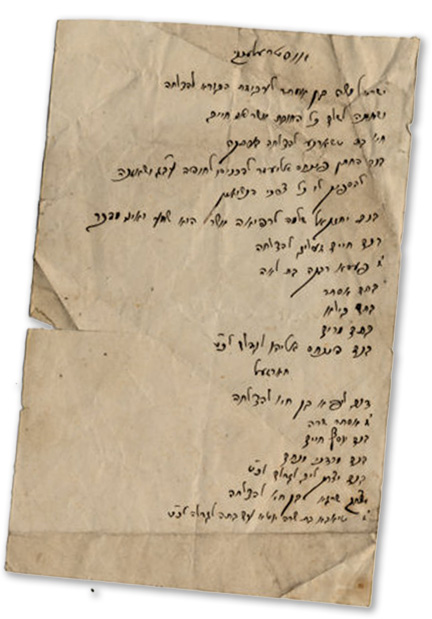

These colorful complaints by everyday Eastern European Jews appear in the vast collection of petitions (kvitlekh) sent to Rabbi Elijah Guttmacher, the Tzaddik of Grätz (Grodzisk Wielkopolski in present-day Poland), whose miracle-working practice flourished in the late 1860s and early 1870s, ending with his death in 1874. Housed in the YIVO Institute in New York, these approximately five thousand petitions open rare windows onto the lives of East European Jews, providing glimpses of their business and family affairs, sex lives, magical beliefs, pious hopes, and grim tenacity as they grappled with the new and unpredictable challenges of modernity. The collection is so rich as to beg comparison with the famous Bintel Brief advice column in the Forverts Yiddish newspaper a generation later, or even the famous Cairo Geniza.

Rabbi Guttmacher, a student of the distinguished mitnaged halakhic authority Rabbi Akiva Eiger and the official rabbi of Grätz, was an unlikely miracle worker. He was one of the first rabbinical leaders to advocate settling the Land of Israel, arguing that it was not sufficient for Jews to simply hope and pray that “suddenly the gates of mercy will open . . . and all will be called from their dwelling places.” Despite this apparent political realism, however, he was much more willing than other non-Hasidic rabbis to intercede with God on the behalf of his petitioners.

It all began when a father burst into the study house where Rabbi Guttmacher was teaching, begging him to expel the demons that had taken up residence inside his son. The boy’s stomach was distended, and he was barking like a dog. Rabbi Guttmacher seized the boy’s hand and recited Psalms with great intention (kavanah), eventually forcing the demons out. As word spread, Rabbi Guttmacher agreed to see other desperate pilgrims, whom he proceeded to heal with what he called “natural means”: fumigations (sometimes demons had to be smoked out), immersions, and, most commonly, through prayer. By 1873, Rabbi Guttmacher presided over a miracle-working enterprise in Prussian Poland that had eclipsed the dozens of Hasidic courts further to the east. When his petitioners tried to pay him the customary Hasidic fee (pidyon), he would simply gesture toward a box of donations earmarked for the founding of the settlement of Petach Tikvah.

“All these miracles were done out of necessity, and were imposed on me by force,” Rabbi Guttmacher would later claim defensively in his book Tzofnat Paneach, a commentary on the fantastic legends of the talmudic sage Rabbah bar bar Hannah. “What was I supposed to do when a mother and father and other relatives brought their children to me crying and shouting for mercy?” In a letter contained in the archives, he complains of feeling besieged by “the broken-hearted who sometimes come here asking [me] to arouse God, blessed be He, to heal them . . . and give them advice.” In 1874, the year of his death, he went so far as to place an appeal in the Hebrew periodical Ha-Magid begging Jews to stop coming to him. Still, Rabbi Guttmacher could not conceal his pride: “Often I have thought, ‘Now who will tolerate the new heretics who say that nothing exists beyond nature?’”

Fifty years later, a network of amateur ethnographic collectors known as zamlers began to fan out across Poland collecting artifacts and jotting down folk idioms. In 1932, in an attic in Grodzisk, some of them came across an enormous trove of kvitlekh that Rabbi Guttmacher had carefully filed away. They brought most of their haul back to YIVO in Vilna, where it received little attention. What the Jewish scholars neglected, however, was perversely appreciated by the Nazis. In 1942, Alfred Rosenberg’s notorious task force, which was dedicated to expropriating cultural property from Jews and other “undesirables,” seized most of the collection, though members of the Jewish “paper brigade” were able to bury a small cache in the Vilna Ghetto. The task force transported the bulk of the Guttmacher archive to the Nazi Institute for Investigating the Jewish Question in Frankfurt, which had been founded to preserve the memory of the world’s soon-to-be-deceased Jewish population. It was, of course, the Institute itself that ceased to exist. In 1945, after the collapse of the Nazi regime, the U.S. army recovered the Guttmacher petitions and returned them to YIVO, which had relocated to New York. The hidden portion was later unearthed in the Vilna Ghetto and restored to YIVO as well. From that point on, these petitions have sat in New York City (although some have made their way to Jerusalem), virtually unread.

The neglect of Guttmacher’s petitioners may be due to the fact that they do not conform to professional historians’ picture of the 19th century as one of rapid modernization. Jewish historians tend to paint a picture of industrialization, secularization, and emigration splashed across a dull backdrop of poverty and stagnant religiosity. They highlight maskilim, budding Zionists, Bundists, assimilationists, and other urban, secularizing elites, at most tolerating a few exemplars of high rabbinic culture. Jewish fiction writers depict older-generation Tevyes looking on helplessly as their daughters shun tradition and court modernity. Jewish artists appear more enchanted by everyday Jews of the Old World. Yet even they cannot seem to refrain from flinging fiddlers, cows, and newlyweds across the shtetl sky.

Hints of modernization do glimmer among the Guttmacher petitions. But petitioners are most commonly preoccupied with finding a match, earning a living, recovering their health, and avoiding the “military fate” of conscription into the Russian Army. Their world is at once enchanted and disenchanted. Shopkeepers calculate profits, hurl curses, and offer up prayers. The ill, beset by both scientifically named diseases and irrepressible demons, consult professional doktorim before finally turning to Rabbi Guttmacher, often apologizing for their momentary lapses of faith.

The petitions remind us that the promises of scientific modernity produced their own forms of disillusionment. Israel Jacob ben Feiga concluded that “all doctors are frauds and liars” after they failed to cure his son, resolving to “seize faith in the strength of God, for He is the best of the doctors. And after that, faith in the efforts of the prayers of the righteous (tzaddikim).” Joshua ben Basha, who had read books in non-Jewish languages and acquired “strange knowledge,” fell into a state of chronic depression. He was sure that the foreign books were to blame.

Instead of welcoming secular modernity, most of Rabbi Guttmacher’s petitioners lived within the rhythms of Jewish law and ritual and continued to be awed by Hasidic rebbes and talmudic geniuses (Guttmacher being a bit of both). Their letters also display increasing irritation and outrage with the “new heretics” denounced by Guttmacher. Many of his petitioners appear to be shifting from a passive, unreflective attachment to tradition to a more conscious and defiant “traditionalism”—a project that sought to shore up piety and ethnic boundaries at the very moment when religion was becoming voluntary and privatized.

Jewish traditionalism in Eastern Europe emerged in a context of severe government pressure on Jews to conform to the rest of the population by shedding their distinctive dress, language, occupations, and education. The heaviest form of coercion was military conscription, which induced a flood of panicky requests to Rabbi Guttmacher to rescue the petitioners or their sons from “falling into the hands of the men of war,” or more generally, “the hands of the Gentiles.” Feigel bat Hadas, whose husband had been “taken by the soldiers,” describes his transformation after years of service:

My husband has been living with me in my house not according to the proper way, but in great strife walks the improper path and constantly plays cards and does other profane things that are not pious. And I cannot suffer this. And because of this he beat me. And now, since he has mingled with the Gentiles, he has learned their ways and does not want to live with me when he returns from his work. May the Admor Shelita [“our Master, Our Teacher and Rabbi, long may he live”] pray to our fathers in Heaven to turn his heart to good, or to arrange a proper divorce (get).

Traditional economic relations were also being unsettled. For centuries, Eastern European Jews and Gentiles had coexisted within fixed economic roles. But the recent emancipation of the serfs, while a positive development on the whole, brought peasants and declining landowners into fierce competition with Jews over contracts and customers. Many petitioners saw the new competition as a threat to the entire Jewish people and asked Rabbi Gutt-

macher to curse their new rivals. Menachem Moses ben Feiga memorably petitioned:

For success in the tavern, and to repel the local Gentile who arose against the Jews and took their livelihood, so that the customers will not go to [the Gentile] and that the scent of his drinks will stink so that they can no longer bear his drinks. And to cause his downfall, for all the Jews and the widows and the orphans need it, for he took their livelihood.

Rabbi Guttmacher seems to have done little to discourage such chauvinist and protectionist sentiments—he even advised a smuggler to hire a Gentile to bring his contraband over the border so that “if God forbid, there was any seizure then [the Gentile] would have to pay.”

Some Jews readily cooperated with the new class of Christian entrepreneurs. But most considered such collusion to be sheer betrayal. Shmuel ben Gitl had once earned an “honorable livelihood that allowed him a free hour to devote to Torah and divine service,” and he had spared no expense guiding his son onto “the path of Torah and knowledge and good deeds.” Now his timber factory was failing because “a Gentile, may his name be blotted out, arose and established a factory next to our town” and hired a Jewish agent “who pursues me” with stiff competition. Shmuel’s predicament was particularly mortifying because “the festivals are approaching, and I am accustomed to donating a lot of money.” Moreover, his children were growing up and “the marriage rites are hanging around my neck; I need to give a suitable dowry to make respectable matches according to my familial status with Torah scholars (talmide hakhamim), especially Torah scholars with distinguished lineage (yichus).” Rabbi Guttmacher would, he hoped, curse his Jewish competitor on the grounds that he had deprived him of the honor and wealth that his piety and generosity had earned him. The frequency of such requests, both explicit and implicit, suggest that Rabbi Guttmacher might sometimes have been willing to comply.

Petitions by traditionalist women can be jarring to modern ears (a woman named Hayya bat Hanka, for instance, complains that she “has not merited a son” and has no dowry for her recently divorced daughter). But they also remind us of a frequently forgotten feature of traditional Jewish society: Most of Rabbi Guttmacher’s female petitioners worked, either alongside their husbands running taverns, or in separate enterprises such as market stalls. Ironically, it was the modern embrace of non-Jewish bourgeois norms that drew Jewish women out of the workforce and relegated them to the domestic sphere.

Crucially, traditionalist Jewish women who worked could escape unhappy marriages without consigning themselves to destitution. The Guttmacher collection contains fascinating cases of women who, rabbinic law notwithstanding, effectively divorced their husbands when they failed to contribute economically or “walk the proper path.” Sarah bat Feiga had married a widower who turned out to be a gambler and “a drinking man,” who contributed nothing to the family’s finances. “So I divorced him through the bet din,” Sarah reports, merely grumbling that, until she came up with her part of the financial settlement she would have to keep feeding him while he wandered around drinking and gambling. A surprising number of women asked Rabbi Guttmacher to help them obtain a get, presumably by means of legalistic finesse and communal pressure.

The traditionalism reflected in many of the kvitlekh addressed to Rabbi Guttmacher expresses an anxiety over what Jacob Katz once described as the Jewish “awareness of other Jews’ rejection of tradition.” Petitioners were scandalized when they learned, for instance, that a fellow Jew “profaned the Sabbath while on business in Prussia,” all the more so if the detractor was an economic rival. Even a smuggler expressed outrage that certain border guards were apostates who had converted from Judaism to Christianity.

But traditionalism was more than reaction. Ordinary Jews continued to value the wisdom of Torah sages over modern rationalism. Most tended to repudiate Western civilization, which they regarded as morally and culturally inferior to their own. Many just wished to be left in peace to study Torah:

Akiva ben Kasa, for Torah and worship and health and livelihood and success. His livelihood is as a tavern and innkeeper, and the business was always meager but he was content with his portion because he had time to study Torah. But now, many arise against his craft, and it is not enough that his livelihood diminished, but they have also caused his Torah study to diminish because of his diminished livelihood. Also, he has several debts to pay off, which are as cruel as snakes and ravens.

Traditionalism was indeed forced to make room for Zionism, Jewish socialism, diaspora nationalism, and acculturation by the turn of the century, but it remained a stubborn counterpoint to secular modernity. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Hasidim and other traditionalists were steadily rebuilding, regrouping, and replenishing their ranks by means of political parties, publishing enterprises, yeshivas, and networks of prayer and study houses. In doing so, they created a viable, institutionalized Orthodox alternative to the new political and cultural movements on the Jewish scene. Their counter-modern mentality is given poignant voice in the thousands of scribbled requests to Rabbi Elijah Guttmacher.

Suggested Reading

Digital Anti-Semitism: From Irony to Ideology

From tweeting trolls to digital incitement, a contemporary history.

Talmuds and Dragons

Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, The Inquisitor’s Tale weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor.

Learning Yiddish After 60

When I was about 10, I had a brilliant idea. If my parents would agree to speak only Yiddish with each other, it would just come to me without effort. I wouldn't have to learn it or study it, I would just wake up one day knowing it.

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In