The Best Unicorn

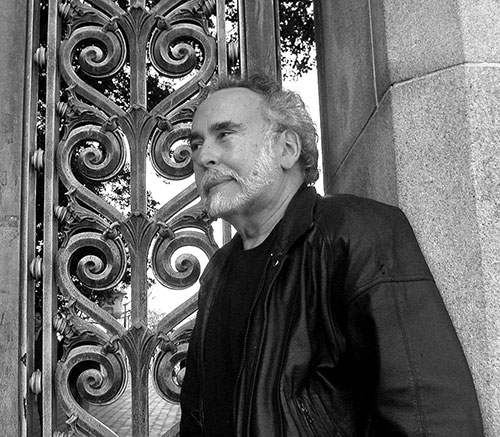

Peter S. Beagle turns 80 this week, which means that he has been writing for 60 years. He was 20 when his first novel was published—the poignant and, given his age, dazzlingly well-realized A Fine and Private Place. It has been six decades and counting: In the last few years alone he has brought out two more novels and a collection of short stories, with new projects scheduled for later this year. Beagle will always be known above all, though, as the author of The Last Unicorn, the 1968 fantasy classic. With its idiosyncratic yet archetypal characters such as the hapless magician Schmendrick, the compassionate Molly Grue, and the unicorn herself, The Last Unicorn is the most beloved book on many a reader’s shelf.

Yet, as Beagle muses in an afterword to a recently published first draft of that novel, he “never consciously set out to be an official fantasy writer.” Although his first novel, set in a graveyard in the Bronx, was also a supernatural fantasy, it came by way of Bernard Malamud and the (today less well-known) Robert Nathan not J. R. R. Tolkien. His second book, I See by My Outfit (1965), was a memoir of a road trip on motor scooters with his friend Phil. Before turning to The Last Unicorn, Beagle worked on, and abandoned, a conventionally realist novel, set in Paris.

So Beagle could have ended up an American Jewish novelist trailing belatedly after Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, an occasional surrealist like Malamud or Cynthia Ozick, an observer of and sometime participant in the counterculture. And in some ways Beagle has been all these things, but they are folded into his career as a fantasy writer.

Timing has a lot to do with this. The Last Unicorn came along just as American publishing, responding to the 1960s surge of enthusiasm for Tolkien, began to determine the contours of, and marketing strategies for, what became the fantasy genre (and what, a few decades later, with the successes of writers like J. K. Rowling and George R. R. Martin, stands tall above realist fiction in sales and increasingly in cultural prestige). Both The Last Unicorn and A Fine and Private Place, after their initial publication by Viking Press, were reprinted alongside editions of Tolkien, Mervyn Peake, Lord Dunsany, and others as part of Ballantine Books’ genre-defining Adult Fantasy imprint in the late 1960s.

In 1977, famed editor Judy-Lyn Del Rey relaunched the imprint, which would later include Beagle’s next novel, The Folk of the Air. In 1978, he wrote the screenplay for Ralph Bakshi’s animated film of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. By the end of the 1970s, then, Beagle was an “official fantasy writer,” though one who would spend his career pondering this turn of events with both gratitude and unease.

Certainly, Beagle writes fantasies of a self-reflective sort. When he writes about magic, he often seems to be writing about writing, which makes sense. After all, magic and writing both involve a mysterious power, inherited from old books yet requiring individual talent, susceptible to formula but ultimately eluding mere technique, demanding solitary toil and no little sacrifice, and pursued in the hope of yet another rare miracle.

Beagle, who wrote an excellent debut novel before he was 20 but had sometimes decade-long stretches between the ones that followed, is especially attuned to the writer’s uncertainty. “Did you see me?” Schmendrick excitedly asks the unicorn when, after years of failure, he finally accomplishes his first great work of sorcery.

“Yes,” she answered. “It was true magic.”

The loss came back, cold and bitter as a sword. “It’s gone now,” he said. “I had it—it had me—but it’s gone now. I couldn’t hold it.”

A related theme in his books is youth and age: the self-defeating callousness of ambitious young upstarts and the prickly insecurities of never-quite-established-enough elders. The Folk of the Air, which is much better than one would expect from a novel about medieval reenactment fanatics in 1970s Berkeley, California, turns on a battle between a contemptuous 15-year-old sorceress and an ancient mother-goddess. “Immortal? You still think you’re immortal? You fat bitch, you fat old walrus, you’re dead now, I’m standing here watching you rot,” says the 15-year-old with that famous Berkeley politesse.

Similarly, Beagle’s 1993 novel The Innkeeper’s Song pits a talented but power-mad younger wizard against his elderly mentor. Beagle cites this as his favorite of his own books and has returned in a number of subsequent stories to its world and characters. Yet it’s a curiously uneasy book.

In some ways it is his most conventional fantasy, replete with swords, sorcery, and an exotic vocabulary (sheknaths, targs). On the other hand it is the least reader friendly of his novels, an inward-facing book with an otherwise straightforward plot drawn out by shifting the point of view, chapter by chapter, among characters who seem less like distinct individuals and more like facets of a single psyche. I suspect The Innkeeper’s Song is a midcareer dramatization—or attempt at an exorcism—of the author’s ambivalence about his status as genre writer. “Give me back my blood, as you promised!” cries the younger wizard as he prepares to sacrifice his erstwhile teacher.

Beagle’s uncles were the celebrated Jewish artists Moses, Raphael, and Isaac Soyer—hence his middle initial. His grandfather was the Hebrew writer Abraham Soyer, who gazes from the cover of my copy of Alan Mintz’s study of American Hebraism, Sanctuary in the Wilderness. When an English translation of the elder Soyer’s stories for children, The Adventures of Yemima, was published in 1979, Beagle wrote the introduction. With these roots in mid-20th-century American Yiddishkeit, Beagle’s Jewishness inflects his fantasy writing in ways both direct and subtle.

Beagle’s first novel, which he calls a “Bronx ghost story,” is the story of two couples, one living and one spectral, who meet in a cemetery. Along with its other Jewish characters, the book features a talking raven who predates Malamud’s “Jewbird” by several years. “You think we brought Elijah food because we liked him?” says the raven about its biblical forebears. “He was an old man with a dirty beard.”

More recently, the protagonist of Beagle’s 1999 young adult novel Tamsin is a 13-year-old named Jenny Gluckstein who moves from New York City to rural England when her mother remarries. There she has to solve a mystery concerning the pookas, fairies, and restless spirits that populate her new home. In some ways, the novel is a return to A Fine and Private Place, with its mix of ghosts, talking animals, and skeptical New Yorkers. Yet it is also a secular Jewish confrontation with fantasy’s Anglo-Celtic tropes, from the legend of the Wild Hunt to Rudyard Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill—emphasis on secular.

The Jewishness of Beagle’s books usually works because its particular American Jewish sociology is worn lightly and authentically. In Tamsin, Jenny lights Hanukkah candles, but only in order to protest her stepfather’s celebration of Christmas. “I went completely blank for a moment—Sally [her mother] and I weren’t exactly the most observant family on the West Side—and then I remembered the blessing,” she recounts. “There we were, the two of us, chanting our heads off, praising a God neither one of us believed in.” The main character in the 2016 novel Summerlong is another such Jew, a retired history professor living near Seattle. “Forget monotheism,” Abe grouses, “humans are too much for one measly god.” Abe winds up having a romantic dalliance with, appropriately, a Greek goddess.

Sometimes the Jewishness in Beagle’s books is more oblique. The Folk of the Air, for instance, may not contain anything specifically Jewish, but I’ll wager the title is a Renaissance fair dress stand-in for the term luftmenschen. The Innkeeper’s Song is set in an exotic, vaguely oriental fantasy world, yet it ends with a depiction of what resembles an Eastern European pogrom: “Just bodies up and down the one street, bodies lying in their own doorways, bodies shoved down the well, floating in the horse-trough, sprawled across tables in the square.”

One can point to other Jewish elements in his novels and stories, from Lila the Werewolf, whose lycanthropy is no match for her overbearing Jewish mother, to the nonfiction I See by My Outfit, in which the most compelling episode occurs when the young Beagle and his travel buddy are recognized by coreligionists in Kansas City as a pair of “Yiddisher boys from New York going to San Francisco on a couple of motorcycles”—and, of course, fed and housed for the night.

Yet of all Beagle’s books, the most Jewishly resonant is The Last Unicorn, and it is worth exploring why.

Given that it defined his career ever after, Beagle can be forgiven for sometimes feeling that his most famous book is a bit of an albatross. Indeed, he recently wrote a novel, In Calabria, that describes the travails of a shy Italian farmer (and would-be poet) when a unicorn shows up one day and turns his life upside down. His previously quiet vineyard becomes the center of a media storm, and he is threatened by Mafiosi who want him to hand over ownership of a creature that he isn’t sure he really possesses. The Last Unicorn was made into an unfortunately tepid 1982 animated film (though with an all-star voice cast including Mia Farrow and Alan Arkin), and it seems relevant that the Mafiosi in In Calabria sound like Hollywood studio executives.

Yet unlike the unicorn in the Calabrian vineyard, The Last Unicorn did not just appear out of the blue one day. Beagle began working on the novel in the summer of 1962, but he wrote himself into a corner and left the book unfinished for another six years. In the first draft, the unicorn takes a back seat to a pair of down-at-the-heel devils—absent from the completed novel—who “have outlived their own evil” in a world in which human beings no longer require demons to tempt them. Isaac Bashevis Singer told a similar story in “The Last Demon,” which appeared in English translation two years later. In Beagle’s first draft, the unicorn and the devils wander through a modern city learning how out of place they are. Yet the trope of fairyland’s (and heaven and hell’s) obsolescence was already a familiar one—even Chaucer played with the theme—and in the summer of 1962 Beagle seems to have understood that he hadn’t squeezed more than a few new drops from it.

The final version is another matter entirely. Here, Beagle does not ironize evil; he treats it mythically. He introduces villains, above all the Red Bull, an implacable, destructive force that has been unleashed against the unicorns. Beagle’s depiction of the unicorn’s melancholy quest for the rest of her kind borders on secular post-Hasidic parables of God discovering what has become of His Jews in the wake of the Shoah. “Wherever she went,” Beagle writes, “she searched for her people, but she found no trace of them.”

Though the novel cannot be reduced to allegory, its language is infused with suggestive parallels to God and the Six Million. The unicorn repeatedly refers to the other unicorns as her “people.” “How terrible it would be,” she says ominously, “if all my people had been turned human by well-meaning wizards—exiled, trapped in burning houses. I would sooner find that the Red Bull had killed them all.”

Beagle’s unicorn resembles a god who has been living apart from the world. When the unicorn leaves her timeless forest she enters into history and is shocked and saddened by what she discovers, not least that human beings are no longer able to recognize her. “There has never been a world in which I was not known,” she muses, surprised when a farmer takes her for an ordinary mare.

Some of the novel’s resonances are Christian as well. How could they not be when the medieval unicorn was a symbol for Christ—and when the novel’s unicorn is transformed into a human being? In order to save the unicorn from the Red Bull, Schmendrick turns her into a princess and then explains that she has now entered the domain of fairy tale: “You’re in the story with the rest of us now,” he says apologetically. Yet this fairy tale incarnation doesn’t follow the Christian story; the now-human unicorn does not herself atone or make sacrifice (one of the other characters does), and we are reminded that, unlike Jesus, “she is a story with no ending, happy or sad.”

Beagle’s interest in the Jewish dimensions of his tale comes through in both periodic allusions—Molly Grue making “bricks without straw” or the Sodom-like town of Hagsgate whose citizens warn “we allow no strangers to settle here”—and the main contours of the plot. The unicorn discovers that her people have been literally driven into the sea, a reversal of the exodus (“The Red Bull,” we are told, “did not know her”) that also echoes Arab designs on Israel at the time of the novel’s writing.

The novel’s bittersweet ending involves a farewell to God—the unicorn departs, though she is reassured that “[m]y people are in the world again”—and a fragile affirmation of secular human agency. “I do not think that I will ever see you again,” says Schmendrick to the unicorn when she visits him one last time in a dream, “but I will try to do what would please you if you knew.”

The Last Unicorn is not the “Jewish Narnia” I once, perhaps unwisely, asked for. Yet with its lantern-lit dreamscape, tender and drenched in intimate sorrow, it is a classic of postbelief. Through Beagle, fantasy literature for a moment touches the language of the Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein, also writing after the destruction:

The God of my unbelief is beautiful.

How nice is my feeble God

Now, when he is human and unjust.

How graceful is he in his proud downfall,

When the smallest child revolts

Against his command.

Through sea and land,

We two shall ever wander and wander together.

(Translation by Benjamin and Barbara Harshav)

Suggested Reading

Why There Is No Jewish Narnia

So why don’t Jews write more fantasy literature? And a different, deeper but related question: why are there no works of modern fantasy that are profoundly Jewish in the way that, say, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is Christian?

Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

A new batch of Israeli fantasy books may not contain Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

The Inklings

Leo Strauss may be as devastating as C. S. Lewis in his criticism of facile and destructive dogmas, but Hollywood isn’t planning a film version of Strauss’s Natural Right and History any time soon.

No Jewish Narnias: A Reply

Michael Weingrad responds to readers of his essay on the dearth of Jewish fantasy literature.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In