A Good Second Choice

One of the things you get for giving a talk at the Sede Boqer Colloquium at the Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Zionism is a free book of your choice from Ben-Gurion University Press. I made my selection a month before my lecture this past June and was surprised when I eventually saw that the volume I had been given was not my first but my second choice. I couldn’t really complain, though. The previous year I had received my first choice, and I had not gotten around to reading it yet, in part because it was such a big book. This one, David Barak-Gorodetsky’s Yirimiyahu be-Tzion: Dat u-politika be-olamo shel Yehuda Leib Magnes (Jeremiah in Zion: The Religion and Politics of Judah Leib Magnes) was a lot smaller, so I put it in the queue ahead of my other new acquisitions in the bookstores of the Holy Land, and especially in the bookstalls set up by dozens of publishers in the First Station in Jerusalem during Hebrew Book Week.

Leafing through the book on the plane back to the United States, I saw that the author had spent some time comparing and contrasting Magnes with another American Reform rabbi who played a major role in the history of Zionism: Abba Hillel Silver. I had done that myself in a piece I wrote for Mosaic six years ago, and I was very curious to see how Barak-Gorodetsky, who is both an academic and a Reform rabbi serving a community in southern Israel, dealt with the same question. So I went back to the beginning of the book and started reading.

Yirimiyahu be-Tzion is a solid work of intellectual history, devoted above all to understanding Judah Magnes as he understood himself, sympathetic but honest, and attentive to the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his thinking. In the end, however, Barak-Gorodetsky, who has considerable respect for Magnes, left me thinking somewhat more highly of Magnes but did not disabuse me of my previous, rather unfriendly opinion.

I had portrayed Magnes as a man who, like Silver, had been for a long time a nonpolitical and cultural Zionist but who, unlike Silver—who had become a fiery advocate of Jewish statehood—had failed to grasp, despite the Holocaust and intractable Arab hostility, that Zionism’s cultural and spiritual aims were unattainable without Jewish political independence. Indeed, he fought tooth and nail up to the very end (May 1948) to prevent the creation of the State of Israel.

Barak-Gorodetsky gave me, in the end, a much deeper understanding of Magnes’s understanding of religion and politics in general and, in particular, of how Magnes persevered in his idealistic rejection of Jewish sovereignty under circumstances that had led other more or less like-minded thinkers to reconcile themselves to Israeli statehood.

An eclectic thinker indebted to the founders of classical Reform Judaism, Ahad Ha’am, the leaders of the American Social Gospel movement, William James, and Karl Barth, among others, Magnes was a rabbi whose connection with God was by no means as strong as his moral beliefs. This is not to say that his religiosity was anything less than genuine. One of Barak-Gorodetsky’s main aims in this book is to correct what he sees as the failure of prior historiography to understand the deeply religious roots of Magnes’s political thought. He succeeds in doing so, but he elucidates at the same time the precariousness of his faith. “Magnes’s religious experience,” he writes,

was one of inability to communicate with God, and of God’s hiding of his face from him. But not only did this hiding of his face not prevent him from engaging in political-moral activity, it actually obligated it, for political activity is the attempt, to utilize an image employed by Barth, “to make one’s way to the coast of God in a sea that belongs to God,” even though reaching the coast is impossible. Personally, this is certainly a tragic political outlook, but it nevertheless suffices to undercut the historiography that tends to regard Magnes as naive for believing in the possible success of his political activity.

Seen in this light, Magnes’s futile efforts on behalf of a binational state—especially in the aftermath of World War II, when it was unmistakably apparent that there was no Arab interest at all in anything of the sort—look very different. Magnes was not blind but was doing what he felt he had to do, regardless of the outcome. Nevertheless, it is precisely this righteous disregard of the likely impact of his actions and the prospects for their success that prevents me from seeing Magnes as my kind of Zionist—or, for that matter, my kind of man. I still prefer Abba Hillel Silver’s more clear-sighted reckoning with the needs of the hour.

It looks to me like Barak-Gorodetsky has come to feel somewhat the same way. For 250 pages he maintains a commendably dispassionate stance toward his subject. Then, in the last few pages, he gets personal. When he was a student, he regarded himself as “closer to the political position of Magnes.”

I lived in Haifa, a city that prides itself on coexistence between Jews and Arabs, and I was close to political groups that called for the advancement of a binational order in Israel. My research interest in Magnes was therefore a natural continuation of my political positions. I saw in the path proposed by Magnes the possibility of linking a liberal religious teaching with prophetic characteristics to a specific sort of politics concerned with the issues of the day and the situation in this deeply divided land. I have to confess that in the course of time, precisely as a consequence of detailed research on Magnes, I began to experience doubts about his political path. I very much hope that the reader will find in this study traces of both of the positions that I represented—the one that sees the moral strength and the idealistic charm of Magnes and alongside it the one that is alert to the danger besetting a liberal religious ideology in its confrontation with the political realm and all its constraints.

Right now, Barak-Gorodetsky’s book is accessible only to readers of Hebrew. In his concluding remarks, he says that he refrained from publishing it first in English for other-than-professional reasons. He indicates, however, that a translation is on the way. I hope so.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

The Audacity of Faith

The career and life of Yehuda Amital—unconventional, unpredictable, and free of clichés.

Spinoza in Shtreimels: An Underground Seminar

A professor and three Hasidim walk into a bar—to study philosophy. True story.

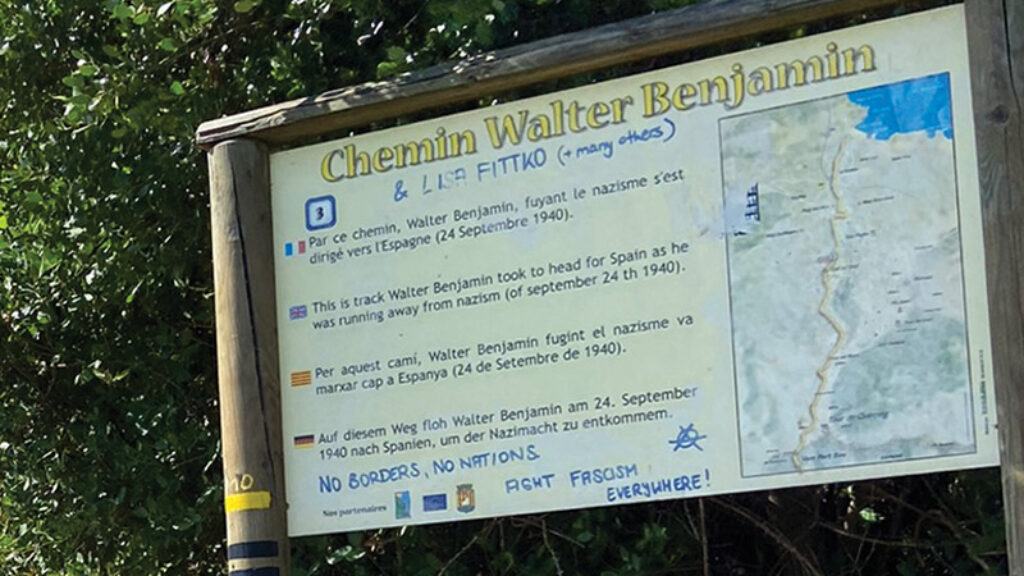

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

A Jewish Nationalist

One can be certain that Magnes was a great university administrator. He got a fine institution on its feet, hired outstanding scholars, raised hard to find funds and attracted gifted students. If that was all he accomplished, then fine.

But, he lived in a foolish dream world, protected with a US passport in his back pocket, which he extracted on the eve of the re-birth of the Jewish State. Frankly, Magnes' name should be allowed to sink deeply under waves of history. His reform background, still another example of narishkeit writ large, was given birth by the few who were prepared then and still so today, to sell out their people, history and Land, for the lentils of being admitted to goyish country clubs and their Jewishly illeterate children marrying non-Jews.

Perhaps the time has come for all these putative Jewish Studies programs to stop nibbling around the edges and actually teach what is means to be a Jew. And, no, it is not tikun olam!