The Ubiquitous Gabirol

In 1931, Shmuel Yosef Agnon moved with his family to a new house in Talpiot, at the southern edge of Jerusalem. It was there that the great Hebrew writer learned of the Nazi murder of the Jews of his home city of Buczacz in Polish Galicia, today Ukraine. In 1944, he published a story fragment, merely six paragraphs long, in the literary journal Moznayim. It was called “Ha-siman,” meaning “The Sign.”

The first-person narrator sits in the beit midrash alone, reciting Azharot. He is amazed to see a “holy man of God” standing over him. The holy man has a question: Do Shabbat prayers in this shul include piyyutim, liturgical poems? Here it’s not customary, the narrator admits.

“And where do they recite piyyutim?” inquires the man. “I remembered my city, its forests and waters, and our big synagogue,” writes Agnon, and the hazzan who knew the poems by heart “because the pages in the old siddur were soaked with tears, illegible.” Says the narrator to the visitor: “There are places where they recite piyyutim, they do it in my city.” Visitor: “And what is the name of your city? “I answered in a whisper: Buczacz is the name of my city.”

And tears flowed from my eyes over the tragedy that had befallen my city, and I did not know if it still existed. He nodded his head and said, Buczacz, Buczacz, and his voice was touched with rhyme, and I knew that this was Rabbeinu Shlomo ben Yehuda Gabirol of blessed memory, whose Azharot I had recited . . .

Rabbeinu Shlomo said, I will make myself a sign. So that I will not forget the name of your city. I stood in awe. Was my city so important that he wants to make a siman for it?

Gabirol plunges into poetry, writes Agnon, medabek atzmo be-charuz: glued to his craft, beading words with devotion. He composes an acrostic, beginning with “Blessed are you of all cities, Buczacz,” transmuting the remaining letters of the name into a perfect poem. But the mystical visitation ends, and the narrator can’t remember the next six lines.

The towering medieval poet will be on my mind as I search my soul on Yom Kippur. His best-known work, Keter Malkhut, a magisterial meld of Jewish theology, Ptolemaic cosmology, and personal confession, is read on Kol Nidre night in various communities. A tiny sample, as translated by Peter Cole: “Who could speak of your wonders, / surrounding the sphere of fire / with a sphere of sky where the moon / draws from the shine of the sun and glows?” As Ismar Elbogen wrote in 1913, in his classic Jewish Liturgy: A Comprehensive History: “No other Hebrew poet knows how to strike so exactly the tone of prayer.”

Shlomo ibn Gabirol statue, Caesarea, Israel.

Little is known of his life. Born in Malaga in 1021, 1022, or maybe 1026, Solomon ibn Gabirol lived in Saragossa and died circa 1057 or thereafter, maybe in Valencia. “All that can be said of him with certainty must be gathered from casual utterances scattered through the multitude of his verses,” wrote Israel Zangwill in his Selected Religious Poems of Solomon ibn Gabirol. He was orphaned young and suffered from a painful skin disease. His massive Azharot (literally, “Warnings”) is a verse rendition of the 613 Torah commandments, all the dos and don’ts in a dazzling acrostic that Gabirol wrote when he was 16, or so we are told.

He has been ubiquitous for centuries, from piyyutim in Orthodox shuls to 11 poems in the supplementary readings of the Reconstructionist Sabbath Prayer Book (1945) to the beloved “Shachar avakeshkha” (“At Dawn I Seek You”) for Shacharit in the Israeli Reform siddur we use at Kol Haneshama in Jerusalem. Ibn Gabirol was also a prolific secular poet and a neo-Platonic philosopher famed in the Christian world as Avicebron, the author of the treatise Fons Vitae (The Fountain of Life), known as Mekor hayim in its Hebrew translation and Yanbû’ al-hayâh in the original Arabic. Mivchar ha-peninim (“A Choice of Pearls”), a rich collection of ethical adages adapted from Arabic, has long been attributed to Gabirol, though his authorship has been debated by modern scholars. But I say, when it comes to Gabirol, print the legend.

For example, how did he die? Nobody knows. In the introduction to his elegant translation of Keter Malkhut, The Kingly Crown (1961), the orientalist Bernard Lewis remarked on “the usual encrustation of fact with myth and interpretation” that frustrates the Gabirol scholar. One famous story, wrote Lewis, “tells of how he was murdered by a jealous Moor, who buried his body under a fig-tree, and was later betrayed when the tree bore an incredibly rich harvest of fruit.” Elsewhere, I have read that the fruit miraculously appeared out of season and that the “Ishmaelite” was hanged Haman-style from that very tree. In any event, by most historical accounts, the extraordinary poet was not a likable fellow. Peter Cole, in his justly acclaimed Gabirol volume, titled his clever introduction “An Andalusian Alphabet.” It begins with “Abu Ayyub Suleiman ibn Yahya ibn Jabirul”—Rabbeinu Shlomo’s Arabic moniker—and charts an acrostic road to Z for Zygote (i.e., the poet’s creative hybridity). Cole’s J section is titled “Jerk”:

The stench of his boasting and sense of self-worth, his truculence and misanthropy, his inability to sustain friendships or stay in one place for any length of time, even his essential sense of the world and time and fate as hostile—all the evidence points to his having been, as [John] Berryman said of Rilke, a jerk.

This belligerent Gabirol is a far cry from the mystical maggid of Agnon’s lachrymose story, but it fits the legend of a violent death. Consider, too, Zangwill’s translation of “Sha’ar petach dodi,” a well-known piyyut recorded by the Israeli rocker Berry Sakharof:

Open the gate, my love,

Arise and open the gate,

For my soul is dismayed

And sorely afraid

And Hagar’s brood mocks my estate.

The heart of the hand-maid’s sons

Is hateful and haughty grown,

And all because of the cry

Of Ishmael piercing the sky,

Ascending and reaching the Throne.

Cole’s translation is faithful to the Hebrew: “mother’s maid” (shifhat immi) in lieu of Hagar, “her child” and not Ishmael, but the point is still clear. Muslim Spain was a perilous place, no less than Palestine in the 1940s.

My first exposure to the immortal poet came in Flatbush in the pages of The Great March: Post-Biblical Jewish Stories, a two-volume set of dramatic tales aimed at third and fourth graders and published by the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in the 1930s. Thanks to my pluralistic parents, by age 10 I knew all about Rabbi Akiva and Saadia Gaon, Shabbtai Zevi and Captain Alfred Dreyfus. But the yarn I liked best was “The Wondrous Tree,” an exciting adaptation of the murder of Solomon ibn Gabirol, written by Rose G. Lurie.

In the opening scene, a Spanish Jewish shopkeeper chats with an “Arabian poet” who dashes off a doggerel couplet: “Ibn Gabirol—a great Jewish poet is he, / But Ibn Gabirol a great poet must not be.”What was that about? asks the shopkeeper’s wife. Her husband replies: “Oh nothing! He’s just jealous of us Jews. They all are. And since he is a poet – he is especially jealous of Gabirol.” Cut to several years later. Gabirol “suddenly disappeared” and a “wonderfully beautiful tree had sprung up” beside the house of the Arab poet. Everyone comes to marvel at the tree, including the curious Caliph. He orders a laborer to dig, and lo, they find the corpse of Ibn Gabirol. The shopkeeper pushes through the crowd, tells the Caliph he knows who killed him. He recounts his chat with the poet: “He sat there a long time and spoke to me about the Jews in Spain. He thought they were getting altogether too great and too rich.” The Arabian protests his innocence. He is whipped with a bamboo stick and confesses. “The Arabian was hanged. And Ibn Gabirol, whom he had slain, lives on forever and ever because of his beautiful poems.” Imagine the indelible impression on a yeshiva boy of the 1950s: it’s all about jealousy.

In 1962, four years before his Nobel Prize, Shmuel Yosef Agnon published a new version of “Ha-siman” (“The Sign”). It was later included in a hefty posthumous collection of Agnon’s Buczacz stories, Ir u-melo’ah,edited by his daughter, Emuna Yaron. (Published in English as A City in Its Fullness, it was edited by Alan Mintz and Jeffrey Saks; the excellent translation of “The Sign” was done by Arthur Green. The book was reviewed in our pages by Ruby Namdar.) The author in his seventies, pondering the Holocaust in his Bauhaus home in Talpiot, expands six paragraphs into the full complexity of his life. The Hebrew speaks volumes in the first sentence:

In the year when we heard that all the Jews in my city had been killed, I was living in a neighborhood of Jerusalem, in a house I had built after the riots of tarpa “t [5629], equal in gematria to Netzach Yisrael.

Shoah, Jerusalem, and God are the DNA of the longer story. The date of the 1929 Hebron pogrom corresponds ironically in Hebrew numerology to the name of the Almighty. The Orthodox Israeli narrator, celebrating Shavuot in a fragrant, vulnerable garden suburb, revisits his Buczacz boyhood. “Ha-siman” redux, composed of 42 short, lyrical chapters, is lush with simanim.

I will focus on a fleeting reference in chapter 32 (equivalent in gematria to the word “lev”: the heart of the matter). Agnon’s autofictional narrator imagines himself in the little shul in his home city. There he sees Hayim the beadle, scrolling through a Torah to the next day’s portion, and Shalom the shoemaker, sitting and reading the book Shevet Yehudah, “just like he did when I was a boy, reading Shevet Yehudah with a pipe in his mouth.” Shalom puffs on his pipe, but it’s empty. Hayim and Shalom (meaning “life” and “peace”) confirm the liquidation of the Jews of Buczacz: Not even a minyan was left. Shevet Yehudah (“Scepter of Judah”), the popular 16th-century chronicle of calamities from Titus to Torquemada, is a perfect prop for the chilling scene, as Agnon converses with the dead.

The author of Shevet Yehudah was Solomon ibn Verga, another Spanish Jew with a murky life story. Expelled from Spain in 1492, forcibly baptized in Portugal, he apparently wrote his book in Turkey, attributing its content to his “wise master, Don Judah ibn Verga.” It was edited and published posthumously by Solomon’s son Joseph in 1554 in Adrianople; it was translated into Yiddish to broaden the readership (Krakow, 1591). The author, whoever he was, seeks to know: Why the Jews? “Lo asah chen le-khol goy,” he laments, turning Psalm 147 on its head: God did not treat any other people as harshly, “though they were more sinful than the Jews!” But Shevet Yehudah is a tricky, postmodern hybrid, way ahead of its time. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, in his modern classic Zakhor, described the book as “a precociously sociological analysis of Jewish historical suffering generally, and of the Spanish Expulsion, in particular, expressed through a series of imaginary dialogues set within the framework of a history of persecution.” Ibn Verga floats a theory in a fictional episode starring a “great and gracious” Spanish king called Alfonso and his confessor-adviser, a churchman named Thomas, as in Aquinas:

I have never seen an intelligent person who hates the Jews. They are hated only by the common people, for good reason. First, the Jews are haughty and always seeking to lord it over others . . . The Sage has said that the hatred which is caused by jealousy can never be overcome . . . so long as they gave no cause for jealousy, they were well-liked. But now the Jew is ostentatious. If he has two hundred pieces of gold, he immediately dresses himself in silk and his children in embroidered clothing. This is something that not even nobles who possess an annual income of a thousand doubloons would do.

Are we hearing right? A survivor of the Spanish catastrophe, hiding behind veils of voice and authorship, blaming Jews for antisemitism? Ashamnu, bagadnu, we confess on the Day of Atonement, but Ibn Verga goes the extra mile. And who is this “Sage” quoted by the wise Thomas? I turn to a footnote in my battered copy of Shevet Yehudah, the 1947 critical edition, inherited from my father: The Sage is the author of Mivchar ha-peninim, the ubiquitous Gabirol. The pearl of wisdom, suitable for memorization: “Kol sin’a yesh tikva l’refuatah, chutz mi-sin’at mi she-sinato kin’a.”“There is hope for healing all hatred except the hatred that is rooted in jealousy.” Does the Sage mean to signal that if Jews acted differently, others might hate us less?

Agnon ends “Ha-siman” in the local shul in Talpiot, a humble wooden shack, where the narrator recites Gabirol’s Azharot. The doors of the Holy Ark open, and he sees the kingly figure of a man. Gradually he realizes this is Gabirol himself, and weeps. As in 1944, the mystical visitor weaves a memorial acrostic that the narrator cannot remember, but “the poem sings itself in the heavens above.” If Rabbeinu Shlomo shows up on Yom Kippur at my shul in Jerusalem—and why wouldn’t he?—I have a question or two to ask him.

Suggested Reading

Mystical Teachings Do Not Erase Sorrow

In Yehoshua November’s new collection, however, it turns out that the difficulties of being a Jewish poet do not primarily flow from being either Jewish or a poet but from the underlying difficulties of life itself.

The Body in Verse

Examining the lost art of the poetic physician. "Know that it is not in your ability to fulfill them / To God alone belongs this power."

Buried Treasure

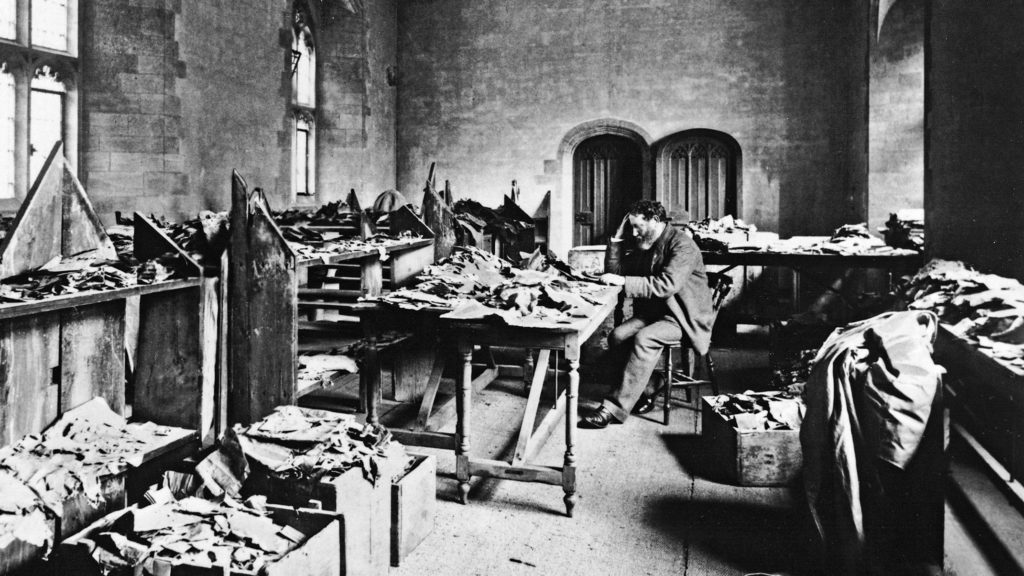

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

Endless Devotion

Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks' new translation of the siddur moves Hillel Halkin to reconsider Jewish prayer.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In