Facing Faces

Nearly every morning since October 7, I open my phone and look at the faces of the war’s most recent victims. I gaze at these portraits fearfully, searching for a familiar face. This mourning ritual must be a feature of life in war zones around the world, in Ukraine, Sudan, and Gaza too. But I dwell among my people, so the images I stare at are of Israelis whom I know, think I know, or could have known: the face of a neighbor killed in her observation booth on the Gaza border; the cheery expression of an acquaintance gunned down at a rave; the serious demeanor of a young soldier who attended elementary school with my daughter, and died early in Israel’s ground campaign. Sometimes, a mistaken identity throws me: How is that possible? I just spoke with Matan, and now I see his picture among the dead?! Oh wait—he has the same first name, and the same brown skin and twinkling eyes as this soldier, but that’s not his last name, and the hairline is slightly different.

The faces of the fallen peer out, strangely prophesying the death they announce, their visages frozen in perpetuity. It is true that, as Roland Barthes once wrote, “ever since the camera was invented . . . photography has kept company with death,” but these pictures quiver with something darker. Never professional, generally happenstance, and always heimishe, the snapshots of the fallen capture carefree, full lives, cruelly cut down.

Like other Israelis, and Jews everywhere, I also look at photos of the hostages, who are, as I write, still held in Gaza by Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and other bad actors who take pictures of themselves in masks as courageous symbols of resistance. The hostages’ faces are not masked, of course. These faces make demands on us to acknowledge their lives—and to rescue them from the shadow of death.

I do not find these pictures in the online ether but on paper flyers emblazoned with the word “KIDNAPPED” in all-caps white letters set against a red background. The signs are ubiquitous, plastering campus bulletin boards, storefronts, streetlamps, and other city surfaces. Yet the flyers are probably best known from viral videos of people tearing them down, usually while being confronted by someone recording them on a smartphone. These little episodes are infuriating, but they are also fascinating in their demonstration of the power faces have to provoke. In some of the most disturbing encounters, the offenders baldly assert that the hostages are not real, or that their faces have been generated by artificial intelligence. For those burning with hatred of Israel, the only way to deal with the moral demand these faces make on us is to destroy them and imagine that they do not exist. Ironically, the act of defacement ends up imbuing the faces on the posters with even greater power, turning snapshots into icons of humanity.

No thinker was more interested in the human face and its power than the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. For Levinas, the face holds the potential to see beyond the claustrophobia of one’s own thoughts and experiences. Although Levinas wrote about the composition of the human face—its aura, apertures, and peculiar geometry—it was not physiognomy Levinas was after, but an ethical encounter:

The face is not the mere assemblage of a nose, a forehead, eyes, etc.; it is all that, of course, but takes on the meaning of a face through the new dimension it opens up in the perception of a being.

About a month after the start of the war, while in New York for the weekend, I heard about a Saturday afternoon demonstration organized by the Jewish community downtown, which called for the freeing of the hostages. I wasn’t sure whether to attend, worried about the real-life encounters I might have with what I understood to be a divided American public. I had also seen videos of recent protests in New York and across the country that had descended into chaos. But when I learned that this would be a silent demonstration, in which participants were to march from Washington Square Park to Union Square carrying enlarged versions of the “KIDNAPPED” posters, I decided to join.

It was a gorgeous day, with thousands of people out, enjoying live jazz at Washington Square, buying apples further uptown at a farmer’s market, and taking in the sparkling autumn sunshine. Dozens of us walked slowly, quietly, holding the placards, from one downtown park to another. I nervously held a sign bearing the face of a twelve-year-old boy named Erez Calderon who has since been freed from captivity (as I write, his father remains a hostage).

To my surprise, there was virtually no friction with passersby; certainly no one tried to take or destroy our placards. In fact, many took the time to gaze at the faces and read the accompanying text. Some raised their gaze and met our eyes as we held the signs. A pair of women whispered words of support to us, an older man offered mournful, encouraging nods. I realized, then, that the true power of the face is not accessible in reproductions like the placards we were holding, but in real encounters between human beings.

“The vision of the face is not an experience,” Levinas writes, “but a moving out of oneself, a contact with another being.”

Suggested Reading

Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

A Hasidic-owned, bicycle-powered tefillin factory in Krakow, Poland.

The Mortara Affair, Redux

Bologna, 1857: A six-year old is taken from his Jewish family to be raised a Catholic. Why are we still talking about this case? An archbishop responds.

Fatal Attraction

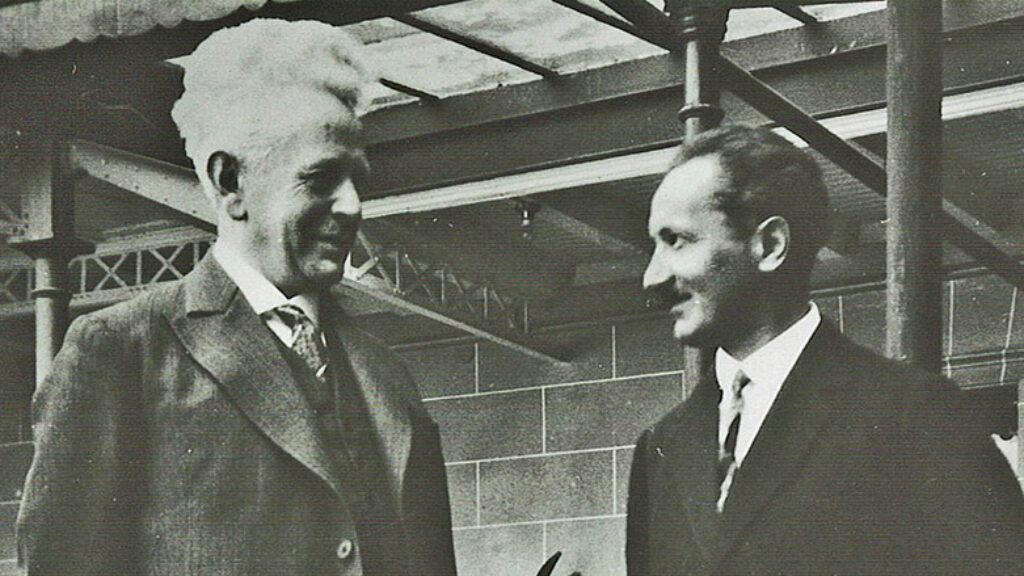

Although Martin Heidegger joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and never forthrightly repented of the episode “no other philosopher had more impact on twentieth-century European Jewish thought.”

What Goes Into Survival: A Report from the Washington Rally

People came by the hundreds of thousands, schlepping by train, chartered bus, overnight flight. Students raised money from relatives. Federations funded last-minute airfare. It was a rally for people who don’t attend rallies.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In