Jewish Identity and Its Discontents

I grew up in a thickly Jewish environment and always felt very much at home in it, but when I was a college freshman it seemed to me, briefly, that continuing to be Jewish was an option I might choose not to exercise. If one didn’t believe in revelation—and I couldn’t—and if ethnic solidarity was rooted in mere prejudice—as I was tempted to think—then what sense did it make to carry on as a Jew? No single piece of writing played a larger part in helping me to answer this question than a mimeographed copy that an older student gave me of a talk that the political theorist Leo Strauss had delivered a few years earlier entitled “Why We Remain Jews.” “What shall those Jews do,” Strauss asked, “who cannot believe as our ancestors believed?” They must be brought to see, he insisted, how disgraceful it is to deny their origins and heritage and to abandon their Jewish identity. And they must understand that even if Judaism is at bottom a delusion, “no nobler dream was ever dreamt.” Strauss didn’t answer all my questions or make me pious, but he kept me loyal.

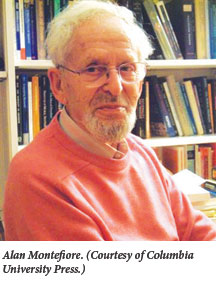

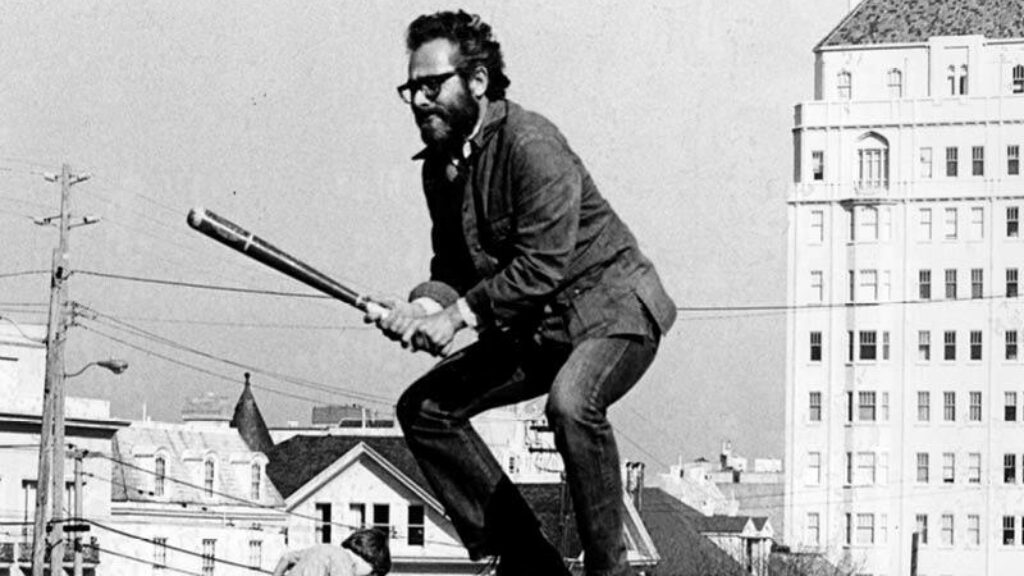

Ever since reading Strauss’ lecture, I have kept my eyes open for new essays and books that revolve around the questions he addressed, especially the ones produced by thinkers and writers who make their living neither as rabbis nor as professors of Jewish thought. John Lennon and the Jews: A Philosophical Rampage, by the American-Israeli professor of Middle East studies Ze’ev Maghen drew my attention in part because it explicitly targets “the current generation of up-and-coming Jews as they decide just how Jewish they want to be, as they debate how much space and how much importance to give Judaism and Jewishness in their lives.” The British analytic philosopher Alan Montefiore’s A Philosophical Retrospective: Facts, Values and Jewish Identity sets no such goal. But both books represent serious intellectual efforts to grapple with the question of preserving Jewish identity and both of them are eminently worthy of consideration.

The fact/value distinction to which Montefiore alludes in his book’s title, and on which his entire argument rests, is one that Leo Strauss spent a fair amount of time combating. In his book Natural Right and History, Strauss maintained that a sharp bifurcation between facts and values, one that entails the rejection of the possibility of any genuinely true value system, inevitably leads to nihilism and absurdity. He might nevertheless have regarded A Philosophical Retrospective in a somewhat positive light. Agreeing, in effect, with Strauss, that facts and values always remain to some extent “obstinately intertwined,” Montefiore doesn’t simply consign Jewish identity to the realm of arbitrary values; he seeks to clarify whether, for the individual Jew, it is not an inescapable fact.

In his own case, Montefiore explains, the issue is

effectively one of whether the facts of my own identity, as the elder son of my particular Jewish family, together with those not so easily determinate but still relatively indisputable facts concerning the generally accepted nature of the relevant family and community traditions, were so tightly tied to a certain set of positive and negative obligations as to render escape from them virtually unthinkable—so unthinkable as to make it impossible for me to acknowledge my own evident family and Jewish identity without thereby recognizing it as equally evident that these obligations were truly incumbent upon me.

That a prominent analytic philosopher like Montefiore has felt impelled to dwell in this way on his relationship to his ancestry no doubt has a lot to do with the pressures to which all British Jewish intellectuals were exposed in the middle of the 20th century, as well as to the very special baggage that he himself carries. He is related to the still-celebrated 19th-century philanthropist and activist Moses Montefiore and a direct descendant of Moses’ great nephew Claude Montefiore, the leading theologian of liberal Judaism in Great Britain in the early 20th century. A heritage of this kind is not something that one can easily slough off, even if one is a non-believer, as Alan Montefiore appears to be.

It is, at any rate, the obligatory character not of the Jewish religion that preoccupies him, but of Jewish identity, however understood. And while he poses this question near the beginning of his book, he does not rush to answer it. He muses, instead, in a somewhat autobiographical manner about the alternative and rather complicated definitions of Jewishness that are in competition with one another other today. Among the matters on which he voices his opinion is the nature and viability of a fully secular Jewish identity. This option, he is willing to grant, may make perfectly good sense, but he questions whether it can persist, either in Israel or the diaspora, without “the continuing survival of a core community or variety of communities of religiously committed and actively practicing Jews.”

When Montefiore finally returns to the question with which he began, his conclusion is straightforward, even if he couches it in characteristically complex language: “an insistence on the impossibility of any logically compelling passage from nonevaluative premises, be they factual or ‘analytic,’ to evaluative conclusions constitutes both an expression of and a major conceptual underpinning of a fundamentally individualistic culture, ideology, worldview, or whatever.” In other words, however one chooses to weigh the fact of Jewish identity, it cannot turn into a value, at least not in the eyes of the large majority of modern Jews who share the cultural orientation he has described. And even those Jews who prefer a society that does not make room for broad-ranging individual distinctiveness and autonomy will be exposed to a certain risk, “if their language of thought and the form of life of which it is both an expression and a part do make such concepts available to them.” If such is the case, they will find themselves “unable to refute the arguments of those who may rely on the fact/value distinction in defense of the principle of individual value responsibility and all that it implies.”

Who does this leave out? Only the most retrograde, ultra-Orthodox enclaves composed of people who are out of touch with modernity. Yet even these people cannot be disregarded. However greatly outnumbered and utterly marginalized they might be, they aren’t necessarily wrong. Their religious “culture, ideology, worldview, or whatever” provides a different answer to the question of Jewishness, one that cannot be disproved. At least not by our author, who announces that he does not believe that in matters of this sort it is in principle possible to arrive at any “definitive and rationally indisputable closure.”

How much of an obligation to identify and live as a Jew Montefiore has in fact chosen to assume is something that he makes no effort to clarify in this book. All we can conclude is that to the extent that he has shouldered any particular responsibilities at all, he has done so voluntarily. The mere fact of his birth into a Jewish family, and a very prominent one at that, did not, in his opinion, saddle him with any logically inescapable duties whatsoever.

Montefiore’s rather bloodless and noncommittal essay makes no attempt to change the lives of any college freshmen who might be in the throes of deciding what it means to be Jewish, nor is it likely to have such an effect. On the one hand, his book offers no basis for a rational affirmation of one’s Jewish identity. On the other hand, it neither condemns nor encourages those who place a positive value, without good reason, on solidarity with the Jewish past. At best, one might say, he leaves the door open to an undisguised irrational affirmation of one’s Jewish identity. This is a door through which Ze’ev Maghen is only too happy and proud to stride.

An American-born immigrant to Israel, and a professor of Arabic literature and Islamic history at Bar-Ilan University, Maghen has written a book that fully lives up to its subtitle “A Philosophical Rampage.” In his strident affirmation of Jewish identity and faith, he lunges rather wildly for whatever verbal weapon will serve his purposes. Resorting on almost every page to italics, bold print, huge letters, and multiple exclamation points, he brandishes Talmudic adages, citations from Star Trek episodes, sports analogies, tales from his regular tours of duty in the reserves, and aphorisms from Nietzsche to make his points.

Maghen describes himself as someone “who remains to this day . . . a full-blown child of Western philosophy.” But if this is so, he is a rather rebellious son. Deriding John Lennon’s utopian vision of a world without countries to die for or any religions, he can explain in quite reasonable terms why the world should not be homogenized but “should optimally resemble a tapestry of distinctive families, or groups, or peoples, or nations.” But when he has to explain why someone of Jewish birth ought to weave himself into this general tapestry as a member of the Jewish people rather than as a member of some other group to which he happens to belong, or wishes to belong, he is at a loss for a rational answer. “I don’t know,” he admits. This is not really a rational matter but an emotional one, something that belongs to “the kingdom of the heart.”

When Maghen recommends to his readers not to resist this emotion but to surrender to it, he emphasizes the benefits of doing so. Jewishness, he insists, is uplifting. It takes us out of the “prosaic mundanity” of the “daily drudge” and brings us into a sphere that is “powerful, exciting, fathomless, and beautiful.” If you are a Jew, “you happen to have lucked out.”

If you only will it—enough to work at it—you can extend your arms and touch the eons and the millennia, you can suck in the insights and bask in the glory and writhe in the pain and draw on the power emanating from every era and every episode and every experience of your indomitable, indestructible, obstinately everlasting people.

“In a word,” Maghen says, “you can be HUGE.”

The first major section of the book, devoted to “the challenge of universalism,” concludes on this inflated note. In the next section, which parries “the challenge of rationalism,” Maghen moves from the articulation of an allegiance that merely transcends reason to an all-out assault on the rule of reason. What starts as a semi-comical defense of Jewish ritual practices quickly turns into a fierce assertion of the superiority of Jerusalem over Athens (to put things once again in Leo Strauss’ terms).

Maghen begins by regaling us with an account of the undeniably absurd lengths to which he and some of his friends in Jerusalem regularly go to prepare their own, halakhically unimpeachable Passover matzah. He tells us, among other things, how in the search through the Judean hills for just the right kind of natural spring water to use in the baking process, he once found himself “dangling from the end of a thirty-foot rope lowered into the midst of a pitch black grotto, trying (and miserably failing) to fill a five gallon Jeri can with one hand, and doing my best to disregard the various sliming, slithering, swimming, and swarming creatures that called this place home.” “Can anybody,” he asks, after describing the entire operation of which this was just one part, “point to the rational, sensible, explicable side of this meticulously prescribed and punctiliously executed derangement?” But that, he says, is precisely the point. “The Jewish religion is quite simply a big old fraying suitcase stuffed to the bursting point with endless examples of the most unrelieved and unrepentant irrationality.” If Maghen is unbothered, and even pleased, by the fact that Judaism “makes absolutely no sense for this day and age,” it is because he is so certain that being completely reasonable is a worse than fruitless way to approach life. Rationalism, he fears, “will be the death of us,” unless we work our way out of it.

With the same sense of urgency that Friedrich Jacobi railed in the late 18th century against Lessing’s alleged Spinozism, and with kindred convictions, Maghen warns that rationalism inevitably leads to determinism and nihilism. The “rational or logical mindset (if followed consistently)” always leads to the conclusion that “thoughts, feelings, memories, hopes, love, hate, life itself, are nothing but the purposeless and predictable interplay of little bits and pieces of heedless floating stuff.” Unlike Jacobi, however, Maghen does not escape this abyss by means of a leap of unequivocally religious faith. What he calls for, once again, is only the “subjection of the head to the heart.“

At bottom, Maghen proclaims, “love is a better motivation than Truth (this book’s thesis in seven words).” What he means, above all, is love of one’s own people, “for nothing on Earth or in heaven,” not even God, “ought to be more sacred in our eyes than those we love the most.” Indeed, Maghen goes so far as to applaud the “avowed atheist” Vladimir Jabotinsky’s statement that “My God is the Jewish People,” and proclaims, in his own name,

that more than for any other reason, I personally perform “irrational” Israelite ritual and stuff my life silly with Jewish law and lore, because it brings me closer to the folks I love, binds me to them throughout all their generations and habitations, resurrects them for me and lets me clasp them in my arms.

As high as the Jewish people ranks, however, in Maghen’s scheme of things, it doesn’t altogether usurp the place of God, to whom he gives significant attention in his book. He recalls the God of the Bible, who

was most emphatically and unabashedly possessed of all of the juiciest characteristics, propensities, aspirations, needs, emotions, quirks, idiosyncrasies and yes, even many of the weaknesses and shortcomings that are found in—that run the lives of—human beings.

In a passage reminiscent of Spinoza’s blunt reminders in the Theological-Political Treatise of what the Bible really says, Maghen notes that the biblical God was not an impersonal entity but became happy, was sometimes sad, got mad, went apoplectic, calmed down, took a nap, boasted, made mistakes, changed His mind, etc. He follows this sketch with a sorrowful scream: “WHERE IS THAT GOD?” Unlike Spinoza, Maghen misses this “flexible, emotional, imperfect Deity.” And he knows exactly where He has gone. He has been “kidnapped,” he explains (again, not unlike Spinoza) by Maimonides and the other Jewish philosophers. On the basis of theological notions derived less from the text of the Bible than from the writings of Aristotle, they have utterly deanthropomorphized and denatured Him.

Maghen himself is prepared to rescue the God of his ancestors from His intellectual abductors and to integrate Him once again into his own life and that of the Jewish people. But not before he has arranged something of a personality makeover for the Lord, aimed at reducing the problems that might result from such efforts. Maghen is aware that the God of the Torah demands of His people “an absolute and unqualified compliance” with His ordinances. But the God who created us in His image, he says, can hardly have intended to deprive us of our freedom. True, if He were indeed “the cold and calculating cogitation machine that the religious rationalists say He is,” then He clearly wouldn’t be at all “amenable to the notion of disobedience or rebellion.”

But if God is the mushy-gushy, lovey-dovey, let-Me-show-you-My-wallet-stuffed-full-of-my kids’-pictures paternal super-softy that Jewish tradition (when read without Greek glasses) almost invariably describes Him to be, then the situation is vastly different. Then God is not dead-He’s Dad.

And

does Dad really want his children to spend the rest of their lives doing everything he tells them, never deviating so much as an iota from his dictates, never defying, never challenging, never displaying the slightest independence?

Of course not. More than He wants us to obey Him, our heavenly father wants us to be utterly independent to observe His commandments as we see fit, “un-coerced by any authority,” just as He is. This has a decidedly unorthodox ring to it, and Maghen readily confesses that it represents “a rather far-fetched and chutzpadik Midrash of my own.”

It’s hard not to like John Lennon and the Jews. Maghen’s emotional attachment to his own people may not be infectious—he himself recognizes how difficult it is to instill love via argumentation—but it is attractive and refreshing. He makes a valiant and largely successful effort to address vitally important questions in a language that is both sophisticated and hip, although its rather dated, boomer-era character may not greatly enhance his ability to reach out to contemporary youngsters. Aware that his proud ethnocentrism will raise the eyebrows of readers who know something about nationalism’s excesses, Maghen does his best to lower them. His “affection-based solidarity” does not lead him in any way, he tells us, “to begrudge other national communities the same powerful affections for and fierce pride in their own people.”

The real weakness of John Lennon and the Jews, in my opinion, lies not in its nationalism but in its theology, or perhaps I should say its theological stance, since the book is so nearly devoid of theological reasoning. Maghen’s nationalism is, admittedly, irrational, based on a feeling that cannot be adequately justified. But the object of his love, the Jewish people, is unarguably there. The same cannot be said of his God. Nor does he himself try to say it. He doesn’t make any argument, either, that the biblical narrative ought to suffice to prove the existence of the God of Israel.

The closest Maghen comes to endorsing the Bible in this way is in his account of his disturbing encounter in the Los Angeles airport with three obviously Israeli Hare Krishna members, “energetically hawking copies of Vedic texts to the few passers-by who didn’t ignore them.” After a short conversation with them, he reached into his knapsack

and boldly whipped out the Five Books of Moses (thwack!). “That’s not your book,” I cried, indicating the decorative Bhagavad-Gita Ofer was clutching to his breast like it was a newborn infant. “This”—and I resoundingly slapped the raggedly, worn-and-torn volume in my own hands-“This is your book!!!”

This didn’t satisfy his immediate audience, Maghen tells us, and it isn’t good enough for us skeptical moderns either.

But this isn’t really all that our author has to say with respect to the Bible. He does, after all, miss the biblical God and does his best to bring Him back into the picture. Yet when he finally manages to do so, God has been dramatically transformed, turned into a vastly more self-effacing and permissive Deity than the one we knew. He wants us to be as free as He is, Maghen tells us, but where did he get that idea? From “Jewish sources,” he says, alluding, among other things, to the famous Talmudic passage in which God is portrayed yielding to a rabbinical interpretation of the Law that differs from His own and chuckling that “My children have defeated me.” But this recognition on the part of the rabbis of their own right to construe the Law as they see fit is, as Maghen surely knows, a far cry from an enthusiastic endorsement of a society where no one is ever coerced by any religious authority.

Whatever Maghen says, I think his conception of the Deity’s relation to man derives at least as much from foreign sources as from Jewish ones. It is certainly not from the Bible that he acquires the idea of personal freedom as an indispensable human possession. The Bible doesn’t even have a word for freedom in the sense that we understand it. (Cherut had different connotations in ancient Hebrew, and in any case makes its first appearance only in the coinage minted during the Bar Kokhba rebellion.) And it isn’t from rabbinic literature either. It comes from modern rationalist thinkers—not the ones he derides in his book but others, such as John Locke, whose name doesn’t appear in its pages.

Alan Montefiore’s A Philosophical Retrospective leaves its readers without any hope that reason can provide a rationale for remaining Jewish, but with the consolation that those who set reason aside and continue to value their Jewish identities cannot be proved to be making a mistake. Ze’ev Maghen doesn’t just make allowances for unreason; he revels in it—but only up to a point. If Maghen were fully consistent, he would not only miss the biblical God, he would welcome Him back, without any reservations.

Maghen himself is obviously too much of a free spirit to make such an admission. If he weren’t I don’t think he would have much of an audience. As it is, he clearly wishes to spread his message beyond the ranks of the Orthodox. But if his call to dethrone reason and reinstate the living God included an unqualified demand to assume once again the full yoke of His commandments—who else would listen to him?

John Lennon and the Jews may be catching on. I see some signs that Maghen has struck a chord among young Jews in the United States and elsewhere. His book has received very positive reviews in other publications. Indeed, just as I was putting the finishing touches on this essay we received an unsolicited, highly enthusiastic review of it by an assistant professor at a European university. All of this, I have to say, pleases me. I would love to see Maghen’s book pull ahead of, say, Shlomo Sand’s The Invention of the Jewish People in the Amazon rankings. But I would also recommend to the book’s fans that they not stop with Maghen, that they take into account the fact that other writers (including Leo Strauss) have grappled more profoundly with some of the central issues that he raises.

Suggested Reading

Lucky Grossman

Vasily Grossman was one of the principal voices of anti-Nazi resistance, and a legendary journalist who spent 1000 days at the front during World War II.

People of the Talmud: Since When? A Response and Rejoinder

Talya Fishman and Haym Soloveitchik exchange words on the tosafists.

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

Finding Gold

Herbert Gold spoke quickly, telling ancient stories of friendship with Saul Bellow and run ins with Philip Roth. Between gusts of conversation, he ambled around, wielding his walker so nimbly that it seemed like a form of exercise.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In