Revolution, the Jews, and Hitler’s Munich

“Dear Buber, A very fine theme, the revolution and the Jews,” wrote the Jewish anarchist Gustav Landauer in 1918 at the outset of the short-lived November Revolution. “Make sure to treat the leading part the Jews have played in the upheaval.”

The charged, historically fateful question of Jewish participation in modern radical and revolutionary movements remains highly contested. How widespread and significant was such participation? How “Jewish” was it? How did the organized Jewish community react to these Jewish revolutionaries? To what extent did their visibility and actions contribute to murderous, even exterminatory, antisemitism? And to what extent were Jewish revolutionaries themselves involved in criminal acts of murder and terror? These are vexed questions that Jewish historians have usually evaded or approached apologetically.

Although many historians emphasize the importance of Adolph Hitler’s Vienna experience, in his new book, Michael Brenner insists upon Munich’s centrality for understanding. It was the Jews of Munich, he writes, “who would become the actual targets of his emerging movement”:

The Jews in Hitler’s Munich of the early 1920s paid the price for the failed left-wing revolution and served as a foil for the right-wing revolution to come. They were the first victims of Hitler’s long and twisted road to power.

Of course, Brenner warns us that our knowledge of subsequent events should not color our views. Jewish revolutionaries were not to blame for the rise of Nazi antisemitism. However, “without a Leon Trotsky and a Rosa Luxemburg, without a Gustav Landauer and an Eugen Leviné . . . the world would perhaps have lacked the image of the ‘Judeo-Bolshevik’”—though, of course, Brenner knows that there were other antisemitic Jewish stereotypes always close at hand.

Nevertheless, as post–World War I events unfolded, there was no doubt that the fear of alien Jewish revolutionaries who had brought chaos and violence to traditional, monarchical Catholic Bavaria inspired a violent right-wing reaction. Brenner clearly documents the anxiety of Jewish communal leaders over the actions of Jewish radicals who, they feared, endangered the very existence of their communities. But he begins with a striking counterfactual scenario, which is worth quoting in full:

Let us try for a moment to turn the tables in our thinking about this: if subsequent history had turned out differently, we would have been able to regard this chapter as a success story for German Jews, as an episode of pride rather than of shame. Let us take a moment to imagine that Kurt Eisner’s revolution took root in Bavaria, that the Weimar Republic survived, and that Walther Rathenau remained foreign minister instead of being murdered. We would then write a history of successful German-Jewish emancipation in which the Jewish origins of some of Germany’s leading politicians did not stand in the way of their political advancement, a story reflecting what actually happened in Italy and France. This was the very hope articulated by some Jewish contemporaries for a brief moment in November 1918. In their minds, the fact that Kurt Eisner became the first Jewish prime minister of a German state constituted proof of successful integration.

To be sure, their hope was quickly shot down. Conservative Bavaria was not the ideal place for Socialist radicalism to prosper.

The three successive attempts at revolution were overthrown in almost ridiculously short order. Its Jewish leaders Eisner and Landauer were brutally murdered. Eisner, who led the virtually unopposed and completely bloodless November Revolution of 1918, which overthrew the Wittelsbach monarchy and proclaimed the People’s State of Bavaria, was assassinated in February 1919. On April 7, 1919, the anarchists Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, and Landauer declared the First Council Republic of Bavaria. This lasted a week before being overthrown by Communists, led by the Russian Jewish journalist Eugen Leviné and the Jewish-sounding but in fact Russian-born ethnic German Max Levien.

The conventional wisdom is that when Jews actively participated in twentieth-century revolutionary movements and regimes, they did so as “non-Jewish” Jews who had cut off all ties to Judaism and the Jewish community. But, at least in Munich, Brenner paints a rather different picture. Although these radicals had no formal ties to the organized Jewish community—both of Eisner’s wives, for instance, were not Jewish—they never denied their origins, explicitly opposed antisemitism and, most importantly, were actively interested in their Jewish cultural heritage.

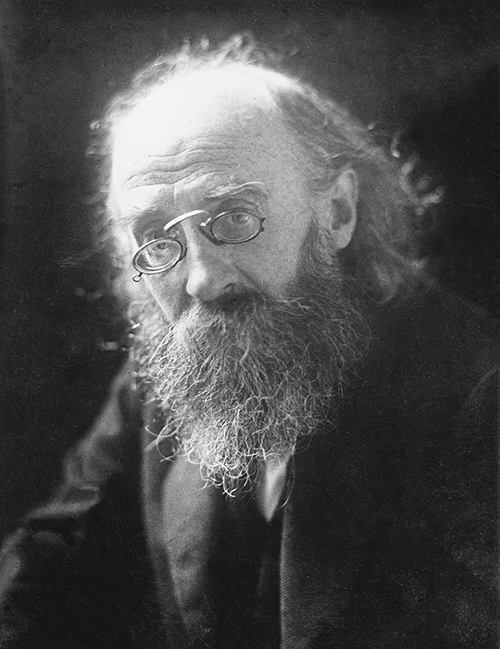

Eisner, chair of the Independent Social Democrats, was an intellectual, a Kantian Socialist whose greatest inspiration was the idealism of the great Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen, who, he wrote, exercised “intellectual influence on my innermost being.” When Landauer eulogized Eisner before thousands of mourners, he proudly declared that “Kurt Eisner, the Jew, was a prophet.” Landauer himself looked like one, and though his relationship with Martin Buber was at times tense, it was always close. “My Judaism,” he declared, “lives in everything that I start and that I am.” “To explore Eisner and Landauer without Cohen and Buber,” Brenner remarks, “would be like reading Marx without Hegel.”

Even Mühsam, an anarchist outsider, parodied his identity in explicitly Jewish terms with a holiday jingle:

Minister and agrarian,

Bourgeois and proletarian,

They all rejoice, each Aryan,

At this same time and wherever they’re able

The birth of Christ in that cow stable.

(Except the people for whom this was fate:

It’s Hannukah they’d rather celebrate.)

“That I am a Jew,” he also wrote, “is something I view neither as an advantage nor as a defect; it is simply part of my essence like my red beard, my bodily weight, or my inclinations and interests.”

As with so many other German Jews, Toller wrote of his complex self-definition: “How much of me was German, how much Jewish? I could not have said,” and added “that a Jewish mother had borne me, that Germany had nourished me, that Europe had formed me, that my home was the earth, and the world my fatherland.” Levin wrote similarly, “Jewish is how my head thinks, Russian how my heart feels.” Of the tangled German-Jewish knot, Landauer declared that “in this relationship I know neither what is primary and what is secondary.”

For all that, as Brenner notes, “Jewish Revolutionaries do not a Jewish Revolution make.” This is not simply because its Jewish participants had removed themselves from the official Jewish community, since in most cases the feeling was mutual, but also because the myth of Jewish solidarity was certainly just that. This was so even among the revolutionaries themselves. Mühsam regarded Eisner as too moderate; Toller skirmished vehemently with Leviné the Communist, “who in turn accused Toller, Mühsam and Landauer of ‘complete cluelessness.’” Moreover, many Jews were also to be found among the conservative reactionaries. “The antisemitic myth of a ‘Jewish revolution,’” Brenner argues, “is therefore just as absurd as the Jewish community’s defensive assertion that all the Jewish revolutionaries were no longer really Jews.”

Two Jewish law students, Franz Guttmann and Walter Löwenfeld, actually tried to overthrow the anarchist First Council Republic. Of course, Jewish attitudes were by no means politically uniform. Although the majority who opposed the Council Republic were left-liberals, we are inclined to forget that many Jews were either conservative or tended even further to the radical right. Some were even active in the ultranationalist paramilitary Freikorps.

Although most Jews voiced their distaste for radicalism privately, Siegmund Fränkel, writing in the name of a traditional Judaism that had nothing “to do with the destructive tendencies of ambitious revolutionary politicians,” penned an open letter—“on April 6, 1919, the eve of the Passover festival 5679”—to the Jewish leaders of the Council Republic:

We remained silent because we feared damaging our community of faith if we shook you off in public and because we hoped from day to day that the sense of responsibility for the religious community from which you or your parents derived would sooner or later awaken in you and make you conscious of the kind of chaos, destruction, and devastation the path you have chosen must lead to.

Mühsam replied that antisemitism hardly needed Jewish revolutionaries to flourish. As compared to Jewish usurers and racketeers, he wrote, it brings “more honor to Judaism when it is associated with idealists and martyrs like Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches, Gustav Landauer, or Eugen Leviné.” Was it an irony that the conservative Fränkel and his family were to be among the first victims of a violent antisemitic attack in the pogrom-like atmosphere of June 1923? Ultimately, this kind of antisemitism knew no distinction between different kinds of Jews.

In other cases the irony was almost grotesque. Eisner’s assassin, Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, wrote that he was going to shoot his victim because he was “a Bolshevik, he is a Jew, he’s not a German, he doesn’t feel German, he is undermining every kind of German feeling, he is a traitor.” Yet, a key motive of Arco’s act was his obsession with his own partially Jewish background. Indeed, he had been excluded from joining the extremist right-wing Thule Society because, as its founder Rudolf von Sebottendorf observed, given his converted mother’s Jewish descent, he was a “Yid.” His mother, Emmy von Oppenheim, was a relative of the similarly converted German nationalist Max von Oppenheim, who as late as 1935 would declare that his nephew Arco was “rightly celebrated as Bavaria’s savior” (see my JRB essay on “Islamic Jihad, Zionism, and Espionage in the Great War,” Fall 2015). A militant Nazi newspaper regretted that it took a non-Aryan to perform the deed: “It is more than a cruel joke of world history that Kurt Eisner, who founded and laid down Jewish domination, had to fall at the hand of a half-Jew.”

Revolutionary Jews stand at the center of Brenner’s study, but he also presents us with a matching collection of extreme right, even antisemitic Jews whose reactionary loyalties were ultimately of no help to them. He particularly concentrates on the now-forgotten Paul Nikolaus Cossmann, editor of the important daily Süddeutsche Monatshefte. An extreme German nationalist and convert to Catholicism with a “physical aversion to everything Jewish,” he was a key exponent of the stab-in-the-back legend that Jews and Socialists were responsible for Germany’s defeat in World War I. He was also at the center of a group of influential Munich industrialists and politicians that in 1923 hatched plans for a Bavarian dictatorship. Eisner and his associates, Cossmann stormed, had raised “the devil’s empire on earth” and were responsible for one of “the greatest crimes in German history.” Of Cossmann, the Social Democrat lawyer Philip Löwenfeld exclaimed, “One of world history’s bad jokes was that the two most important catchwords of the Nazis and the other nationalists fighting against the German republic came from an honest-to-goodness Jew.” Nonetheless, in 1942, Cossmann was deported to Theresienstatdt, where he died as a Jew.

Brenner traces the remarkably rapid transformation of a rather conventionally conservative, intellectually and culturally sophisticated Bavarian city into “Hitler’s Munich.” The lost war, the humiliating Versailles Treaty, the overall postwar social and economic chaos, and, most centrally, the attempted local left-wing revolutions were all grist for a violent counterrevolutionary mill. Brenner demonstrates how this was tolerated, and at times actively encouraged, by various politicians, many judges, the police, and everyday citizens. Members of Munich’s intelligentsia were not entirely immune. The future pope, Eugenio Pacelli, at the time the papal nuncio in the city, could speak of a “Jewish-Bolshevik global conspiracy,” while Thomas Mann (still in his very conservative-nationalist phase) could write of Jewish intellectual radicals that “a world which retains any instinct of self-preservation must act against this sort of people with all the energy that can be mobilized and with the swiftness of martial law.”

“In Munich,” Brenner writes, “hostility toward the Jews, a time-honored topic, had become a political tool with unusual explosive power.” As the brief Socialist Revolution unfolded in 1918, hundreds of inflammatory letters against Eisner and “fellow members of his race” were sent demanding that “Jews like this must now be hunted.” Talk of a pogrom—an event not seen in Germany for centuries—was widespread. The Jewish revolutionaries were often labeled as alien East European Jews, Ostjuden. In fact, Eisner was from Berlin, a Prussian Jew, as was Mühsam; Landauer was born in Karlsruhe. As soon as Gustav von Kahr became prime minister of Bavaria in 1919, he vowed to take “strict action against foreign infiltration by tribal strangers, maintaining the purity of our own people from contamination by foreign elements.” Although Kahr was not immediately successful in this, his expulsion orders against local East European Jews were to some extent successfully carried out when he became state commissioner in 1923.

Yet, in a letter to the editor of Das Jüdische Echo, Helene Cohn declared that there was no longer any distinction between German and East European Jews in Munich in the minds of their antisemitic neighbors. A certain madness, she wrote, had struck people who, afflicted with hardship, could think of nothing else besides “hating and annihilating the 2,500 Jewish families within the walls of the city of Munich.” Brenner does point to certain judges, some government officials, and Social Democrats who resisted the violent antisemitic wave. But, as Thomas Mann put it in June 1923, Munich had become “the city of Hitler, the leader of the German fascisti; the city of the Hakenkreuz [swastika], this symbol of popular defiance.”

Five months later, on the evening of November 8, 1923, Hitler and the National Socialists led a rampage through the streets of Munich, attacking their enemies, racial and political, and taking Jews and Social Democrats as hostages. Brenner writes:

For most of Munich’s Jews, this night represented their first real confrontation with the life-threatening horror of National Socialist terror. They came to realize that, should there be a real seizure of power by Hitler, the National Socialists seriously intended to turn their antisemitic rhetoric from words into deeds.

To be sure, the Beer Hall Putsch was doomed to failure. In retrospect, as Brenner demonstrates, it was also an early test run for the Holocaust. Munich had become Hitler’s laboratory.

Walter Laqueur once wrote about Jewish radicals:

[They] were quite oblivious to one basic existential fact: that they were living in an intellectual ghetto, that the great majority of Germans did not just dislike them, but disputed their very right to have a voice as far as the future of Germany was concerned. . . . Nor did it matter that most of them had no longer any tie with the Jewish community.

Certainly, there can be no doubt that the association of Jews with both revolution and Bolshevism was used to rationalize the enormous violence perpetrated against Jews in Europe for decades, culminating in the Nazi exterminatory genocide.

In an interesting review of Paul Hanebrink’s A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism in these pages (“Lenin and Maimonides,” Winter 2019), Gary Saul Morson accurately noted the disproportionate number of Jews in revolutionary and Bolshevik movements. Of the Russian Empire’s 150 million people, only 5 percent were Jews, yet they constituted about 50 percent of the membership of revolutionary parties. Three of the seven original members of the Bolshevik Politburo were Jews, not including Lenin himself (who was one-quarter Jewish). During the Civil War, some Jews were involved in violent terrorist activities, and, I should add, later in the Stalinist period there were those, like Lazar Kaganovich, first deputy premier of the Soviet Union, who played a central role in the Great mass-murder purge and who were deeply complicit in the collectivization policies that led to the 1932–1933 famine, particularly in Ukraine. The situation was similar in Hungary after the First World War, and in Poland after the Second.

Here we come to the thorny question as to how we as Jews should assess these odious actions. Morson noted that these revolutionaries had all repudiated Judaism and certainly did not see themselves as representing their Jewish communities. As the great Israeli historian Shmuel Ettinger put it:

What was Jewish in them? They were born to Jewish mothers and I not being a racist, do not see anything in it. They were not culturally or religiously Jewish. . . . Are we to say that if a Jew, an individual Jew, is a criminal, does that mean that all Jews are responsible for his or her actions?

But I wonder if it is this simple. Brenner’s revolutionaries, by and large, considered themselves Jews and were even inspired by indisputably Jewish thinkers. And even if, in Berlin, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches had left their Judaism far behind, their colleague Werner Scholem (Gershom Scholem’s brother) was far more ambivalent. His letters to family and friends were sprinkled with Yiddish and German Jewish expressions; while in prison, he vacillated on whether his children should receive a Jewish education, and most critically, unlike his fellow Communist deputies in the German Parliament, he aggressively braved antisemitic attacks.

Moreover, the Bolshevik non-Jewish Jews who participated in the Russian Revolution were not that far removed from the Yiddish language and their Jewish roots. As Jacob Talmon once noted, the simple repudiation of Judaism and Jewish ties does not solve the problem either of identity or responsibility:

To consider as Jews only persons who explicitly affirm their Judaism by positive participation in Jewish activities would be tantamount to approving the statement made in the 1920s by a German Jewish Social-Democratic leader: he maintained that he was no Jew because he had sent a letter of resignation to the Berlin Jewish community—upon which he was asked by a Gentile British friend whether he thought that Jews were a club. . . . Even when they live their entire life in a non-Jewish milieu and have little contact among themselves, Jews still bear within them the imprint of a centuries-old community whose members were regarded by themselves, and by the outside world, as responsible for one another.

Eisner, Toller, and the rest of Brenner’s Jewish revolutionaries were neither terrorists nor murderers. Their Socialist idealism cannot be questioned, although their naivete certainly can. But what of the Jewish Bolsheviks who did have innocent blood on their hands? Morson puts the challenge this way:

I cannot count the number of times I heard that of the four greatest thinkers shaping the modern world—Marx, Darwin, Freud, and Einstein—three were Jews. If Jews claim honor, and honor themselves, for Marx, Freud, and Einstein, how can they entirely avoid responsibility for Trotsky?

This is a good question that Morson plausibly answers by arguing that none of those Jewish Communists acted as Jews. But contrast this with the bracing view of the late historian Jonathan Frankel:

If Jews take pride in Heinrich Heine, Felix Mendelssohn, Benjamin Disraeli, and Boris Pasternak who were Jews by birth but were baptized into the Christian faith, can it be logical—as distinct from comfortable—to disown the “non-Jewish Jews” who as Bolsheviks participated in destroying Russia’s emergent democracy in 1917; in establishing a brutal (albeit “proletarian”) dictatorship; and in provoking a ferocious civil war across the length and breadth of that vast country?

Of course, Frankel argues, this does not mean that fellow Jews should share in their guilt, but “the question of collective shame is another matter entirely.” For insofar as Jews consider themselves as in some sense a people, “nothing is more instinctive than for them to feel pride in its heroes and shame with respect to its criminals.” He concludes that no matter how much non-Jewish Jews renounced their Jewishness and no matter how much their communities preferred to disown them, “the fact is that, in historical and sociological terms, no such exclusion can be justified.”

Many years ago, Gershom Scholem noted the horror of European Jewish scholars when reacting to matters of the Jewish underworld of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In Israel, and the United States, he noted, “such problems can now be taken up and discussed, independent of what anyone else may have to say on the subject and without any regard for external considerations.” Similarly, Talmon once wrote that the complex topic of the role of Jews in twentieth-century revolutions was one that few wanted to touch; the subject was a “foundling, a waif, an abandoned child.”

We have finally reached the point that we can forthrightly confront these issues. Michael Brenner, who currently teaches Jewish history in Munich, has written a book that tells the tragic story of the city and its Jews after World War I without fear or favor and, indeed, in this particular case, without either pride or shame.

Suggested Reading

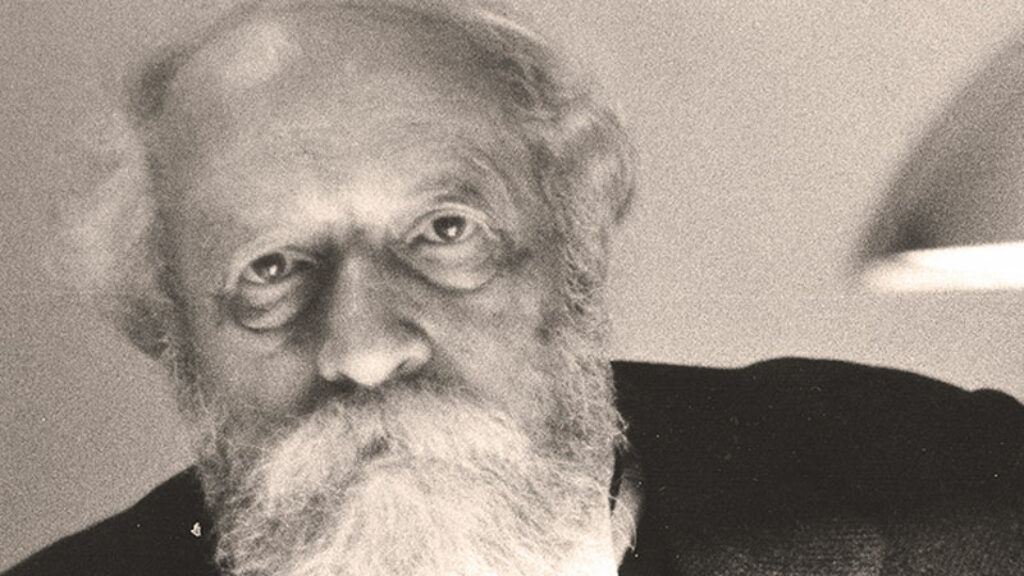

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Valhalla in Flames

To give their "Thousand Year Reich" a patina of tradition, the Nazis co-opted the German and Western European cultural canon.

Cri de Coeur

The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat, and a Murder in Paris.

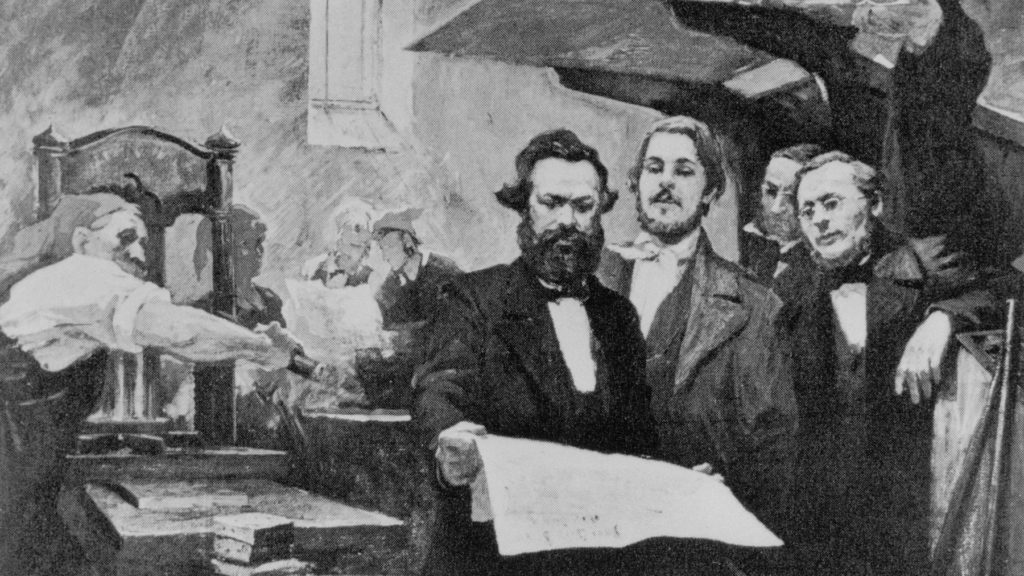

Karl Marx, Bourgeois Revolutionary

Jonathan Sperber's new biography paints Karl Marx as a surprisingly conventional 19th-century paterfamilias.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In