Tread Lightly Lest My People’s Bones Protest: Litvinoff, Eliot, and English Antisemitism

The Institute of Contemporary Arts, just off Trafalgar Square on London’s Mall, has always aimed to provoke, in keeping with the spirit of its cofounder, the anarchist art historian Sir Herbert Read. (I welcome readers to the world of English irony, in which anarchists accept knighthoods.) The institute’s events have generally passed off in a spirit of cultural satisfaction and bonhomie, the English bourgeoise enjoying a bit of gentle épater-ing. But on a memorable occasion in 1951, the mood turned decidedly sour—the audience was shocked, but not in a way it enjoyed.

Read had arranged a reading for emerging poets, and the moment came for the performance of a largely unknown Anglo-Jewish writer named Emanuel Litvinoff, whose first collection, The Untried Soldier, had been published when he was serving in the British Army in 1942. The assembled throng were delighted to learn that Litvinoff’s poem would be an ode to T. S. Eliot, recent Nobel laureate and the most celebrated writer then on the London scene—still more so when it was discovered that, right on cue, the great man had just entered the hall. “Tom’s here!” exclaimed Read, while introducing Litvinoff.

“Eminence becomes you,” began Litvinoff, benignly enough:

Now when the rock is struck

your young sardonic voice which broke on beauty

floats amid incense and speaks oracles

as though a god

utters from Russell Square and condescends

high in the solemn cathedral of the air,

his holy octaves to a million radios.

All just about OK so far, some fitting nods to the early brilliance of The Waste Land and the poet’s uniquely formidable stature; Eliot’s stamp of approval or rejection from the Russell Square office of Faber & Faber did seem to carry the weight of a literary deity in those days. Admittedly, the incense and oracles floating in the cathedral of air might have sounded a bit daring in describing the pronouncements of a High Anglican who flirted with Rome, but not too excessive. Then Litvinoff pressed on:

I am not one accepted in your parish.

Bleistein is my relative and I share

the protozoic slime of Shylock, a page

in Stürmer, and underneath the cities,

a billet somewhat lower than the rats.

Oh dear.

The antisemitic nature of much of Eliot’s prewar verse, including “Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar,” is now well known, thanks largely to the efforts of Anthony Julius, whose comprehensive T. S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism and Literary Form was first rejected by several publishing houses and then earned almost as much defensive scorn as praise on its publication in 1995. Consideration of Eliot’s Jew hatred, alongside his undoubtable genius, is now common, though whether antisemitism was integral rather than tangential to his art, as Julius argued, remains a contested point.

Still up for debate, too, until recently was the question of whether Eliot was “merely” the author of some antisemitic poems or a genuine antisemite—whether, as he and the New Critics repeatedly claimed, art and artist should not be confused. Any doubt on this question has been put to bed by the second volume of Scottish poet Robert Crawford’s critical biography, Eliot After “The Waste Land”—for the Eliot who emerges from Crawford’s deep archival dive not only conforms utterly to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s portrait of a man “very broken and sad & shrunk inside” but as an unquestionably authentic, dyed-in-the-wool antisemite.

He was, for instance, “sick of doing business with Jew publishers” and wondered “why is there something so diabolic about so many Jews”? On spending a weekend in 1939 with the Tandy family who had recently adopted a German Jewish child, he noted that “it” was “a rather nice child and not at all objectionably Jewish to look at.” In perhaps the most shocking moment Crawford unearths, Eliot wrote to his fellow Christian News-Letter editorial board members in September 1941 that “to suggest that the Jewish problem may be simplified because so many will have been killed” by the time the Nazis were finished was “trifling: a few generations of security and they will be as numerous as ever.”

Seven years later, when it was clear that the Nazis had murdered some six million Jews, Eliot did not find the Holocaust sufficient reason to reconsider the inclusion, unedited, of the most egregiously antisemitic poems from his collected works. Seeing no connection between his own prejudices and Nazism, Eliot doubled down, and in the poems went. He had in fact already displayed stubborn form: he read “Gerontion” in public as late as September 1943 (“My house is a decayed house, / And the Jew squats on the window sill, the owner, / Spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp”), when knowledge of the Nazi extermination had already reached England.

It was Eliot’s postwar unrepentance that inspired and enraged Litvinoff. The poems, originally awful but in keeping with cultural norms, were now rendered obscene by context. Like Dryden, Litvinoff knew that forgiveness to the injured doth belong, and then only for the repentant.

What Litvinoff began to do in that second stanza was to personalize the object of antisemitism: I am not welcomed by Eliot, I am Bleistein, and I share the protozoic slime—one of the most loathsome of all of Eliot’s antisemitic images—of Shylock. Moreover, Eliot’s poison existed neither in a vacuum nor only among the dregs of English society but rather at what Julius later called the “canonical” level, from Shakespeare to Eliot.

In “Bleistein,” Eliot had written, “The rats are underneath the pile / The Jew is underneath the lot.” Litvinoff recognized that such lines were not only at home in the English literary canon; they were at home on “a page in Stürmer”—the “Der” cut for scansion but the allusion to Julius Streicher’s antisemitic rag clear. You would separate yourself from Nazism, Thomas Stearns, from that vulgar European disease called antisemitism, not a bit like your own good solid Anglo-American Christian antipathy? Oh, no, you don’t. So the stanza continued:

Blood in the sewers. Pieces of our flesh

float in the ordure on the Vistula.

You had a sermon but it was not this.

I have grappled with that elliptical last line for years. Can Litvinoff have meant to provide a rhetorical opportunity to Eliot for clarification or, better, repentance? It certainly sets up the following stanza:

It would seem, then, yours is a voice

remote, singing another river

Eliot’s sermon, it would seem, was a Christian one, which provided a warrant for exclusion and perhaps worse, but had never, for reasons more

supersessionist than humane, countenanced a genocide.

Litvinoff then addressed Eliot and his fellow Christian antisemites, on so many of whose lips hovered an inevitable “but” following politic declarations of disgust at Nazi bestialism. “But London Semite Russian Paleyou will say / Heaven is not in our voices.” To which Litvinoff, a pale London Semite from the Russian Pale, replies, “The accent, I confess, is merely human.”

Near the end of the poem, Litvinoff dared Eliot to confront the horror of the genocide and ask why his own chilly conscience could not be aroused by it:

Yet walking with Cohen when the sun exploded

and darkness choked our nostrils

and the smoke drifting over Treblinka

reeked of the smouldering ashes of children,

I thought what an angry poem

you would have made of it, given the pity.

The critic Jon Glover was certainly right in observing that there was as much mordant compliment as admonition in the last two lines, a regret that Eliot’s ironic modernist’s eye for contemporary horrors would have been well suited to tackling the wreckage wrought to European civilization by the Nazis, if he could have summoned up an empathy for Jews (“given the pity.”) It continues:

But your eye is a telescope

scanning the circuit of stars

for Good-Good and Evil Absolute,

and, at luncheon, turns fastidiously from fleshy

noses to contemplation of the knife

twisting among the entrails of spaghetti.

Eliot’s theological telescope is focused on Christian absolutes—until it is turned fastidiously on the fleshy noses of Jewish fellow diners. The metaphor of the fastidious poet’s twisting knife among pasta entrails is neatly done. Eliot’s republication of his antisemitic poems was a twisting of the knife into an unhealable Jewish wound.

Litvinoff’s closing stanza was appropriately summary, suitably prosecutorial, utterly heartbreaking, and one I would have every English schoolchild learn by heart. It stands without need for further exposition:

So shall I say it is not eminence chills

but the snigger from behind the covers of history,

the sly words and the cold heart

and footprints made with blood upon a continent?

Let your words

tread lightly on this earth of Europe

lest my people’s bones protest.

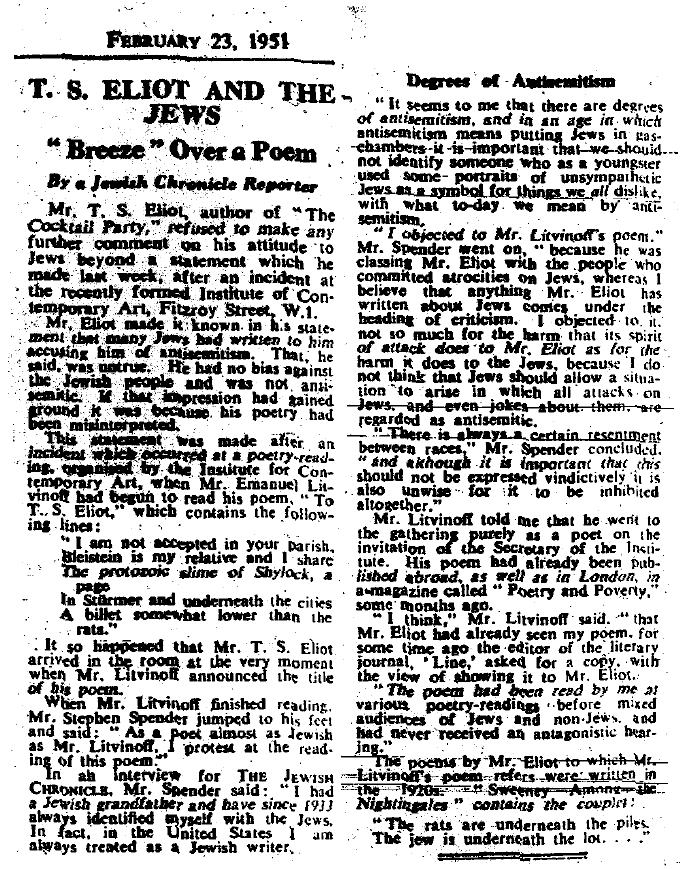

Had the evening seen only the performance of such an eloquently wrathful poem, had it seen only such a courageous display of Jewish self-respect and such a dignified rebuke of respectable antisemitism, then it would still have been enough to be worthy of recall and analysis. But it is the response to Litvinoff that remains instructive. The audience hissed, and both Read and the poet Stephen Spender publicly rebuked him. Read thought it was “bad form.” Speaking to the press after the event, Spender offered this chillingly obsequious banality:

He was classing Eliot with the people who committed atrocities on Jews, whereas I believe that anything Eliot has written about Jews comes under the heading of criticism.

One wonders whether Spender would have considered mere “criticism,” had he been aware of it, Eliot’s observation that Spender himself was “all that I should dislike, being a half-Jew, an invert and a communist, but in whom I feel a curious physical attraction in spite of all that,” as he remarked in a letter to Emily Hale.

So wide was the audience’s indignation at Litvinoff’s offense that apparently the only voice raised in his defense came from Eliot himself: “It’s a good poem, a good poem,” he was heard to mutter amid the tumult. It was, indeed, a good poem, which, like the poems Eliot wrote and most admired, evoked emotion through imagery and persuaded readers with its finely wrought turns of phrase.

Read and Spencer’s willful obtuseness is deeply revealing of English culture’s narrow and self-exculpatory attitude toward Jews and Jew-hatred. To the English, antisemitism was and perhaps still is a foreign, primarily European, disease—all too damned hysterical, too dramatic, and too revolutionary. Until our recent tilt toward hysteria, we English have always prided ourselves, not entirely unreasonably, on a comparative immunity to populist demagoguery. That the British fascist Oswald Mosley never achieved a mass following was not from any great English love of the Jews but because he took the whole business so frightfully seriously, which made him laughable and ripe for Wodehouse’s satire in the form of the ludicrous Roderick Spode. The archetypal English anti-Jew excludes, he politely condescends, he despises, but not based on any pseudotheory. He also does so quietly and is not inclined to base an entire political ethos on his antipathy. It is this that persuades him that antisemitism is for continental savages and never for him.

The relative placidity of modern Anglo-Jewish life certainly plays a part in this English self-regard. After Jews were readmitted to the island in 1656, the historical record tells a relatively uneventful tale, certainly in comparison to Europe. And though our cultural heritage is as the inventors of expulsion and the blood libel, I would wager you could fit the number of non-Jewish Englishmen who know much about 1190, or 1290, or William of Norwich, or Little Hugh into the reception hall of the Institute of Contemporary Art and still have plenty of room for dancing. This self-image and amnesia allow the English to see the Holocaust, too, not as a product of a European antisemitic tradition in which it is implicated—of which it was an early innovator, in fact—but as a phenomenon of the bestial continent.

It is important to note in this context that Eliot’s antisemitic poems, letters, and reported remarks actually reveal a Jew-hatred of an intensity and enthusiasm far beyond the English norm. He seems to have rather gulled the English into thinking that he shared “only” the “mild” anti-Jewish prejudice acceptable to them. It may have helped that even in their grotesque violence, Eliot’s poems retain a characteristic cold poise, though it seems to me that this actually increases their horror compared with, say, the fevered and self-evidently psychotic ramblings of his friend Ezra Pound. They are certainly evidence of a mad pathology, but theirs is a “chilled delirium,” to borrow an apt line from one of them.

Emanuel Litvinoff was the second son of exiled Odessans who fled the pogroms and settled in London shortly before World War I—settled rather unwittingly, in fact, since like so many Eastern European Jews, they had been dumped unceremoniously at the London docks having expected—and paid for—passage to New York. Litvinoff’s father returned to Russia on the outbreak of war, never to be seen again, leaving his wife and children to make their way in the Fuller Street Buildings of Bethnal Green—a London equivalent, on a reduced scale, of the Lower East Side tenements. Litvinoff grew up with the talk “of lands we would never see with our own eyes, of wonder rabbis and terrible Cossacks.”

As an adolescent, he wrangled over the Marxist dialectic with comrades at the Jubilee Street Arbeter Fraint Institut and protested against the Blackshirts at their nearby headquarters. Young Mannie was attracted by the liberation from poverty, tyranny, and antisemitism promised by the glorious revolution. There is a poignant moment in Litvinoff’s memoir Journey Through a Small Planet in which he recounts how a schoolmate fellow radical, Mickey, would refuse to sing the patriotic English anthem “Land of Hope and Glory” when instructed. With each punitive stroke of the sadistic schoolmaster’s cane on Mickey’s hand, Emanuel became more of a communist. But the god failed early enough for Litvinoff that he never succumbed to useful idiocy.

The closing chapters of the memoir afford us a taste of the penury that dogged him through the 1930s. Despite leaving secondary school with a scholarship, which should have allowed him entry to a skilled manual trade, he found every professional door barred to him. He drifted, poverty stricken, through a series of poorly paid jobs, before settling in London’s fur trade. He remembers sometimes being hungry to the point of hallucination and begging for support from the Jewish Board of Guardians. (These were the years of global depression; toward the end of his life, when the post–2008 crash Tory government’s austerity policies robbed him of his Carer’s Allowance, Litvinoff noted the parallels.)

After briefly avoiding military service as a conscientious objector, Litvinoff volunteered for the British Army in 1940 when he realized the extent of the Nazi persecution of Jews. It was at an officer’s ball that he met Irene Pearson, a driver for the wartime women’s Auxiliary Territorial Service. Pearson was smitten with the young major, despite her friend’s warning that—and this is a delightful English euphemism—he was “a bit funny,” being both a poet and a reader of palms. They married mere weeks later, despite Pearson’s father’s antisemitism.

The war brought further life-changing events. Although rising to a more than respectable military rank, a sense of English national belonging ended for Litvinoff when he learned of the fate of the nearly eight hundred Romanian-Jewish refugees on the MV Struma. The ship was refused entry to Palestine in a British sop to Arab intransigence and left to drift in the Black Sea. A Soviet torpedo (in all probability) then hastened an end that the disrepair of the ship would have accomplished before long in any case. Only one of the refugees came out of the disaster alive. “If it were possible to point to one single episode as a decisive turning point in one’s life,” Litvinoff later wrote, “Struma would be that for me. Never again would I be able to think of myself as an Englishman.” In his poem “Struma,” he wrote:

Today my khaki is a badge of shame,

Its duty meaningless; my name

Is Moses and I summon plague to Pharoah.

Today my mantle is Sorrow and O

My crown is Thorn.

It is this same uncompromising Jewish moral indignation, now chilled to the Eliot point, that would enrage Litvinoff’s audience a decade later at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1951.

In 1956, Litvinoff and his wife—who had in the meantime become a leading fashion model and changed her name to Cherry Marshall—visited Russia to stage a British catwalk in Gorky Park as part of the cultural diplomacy between Great Britain and the USSR. Nahum Goldmann, who was then president of the World Zionist Organization, asked Litvinoff to deliver a message to the chief rabbi of Moscow while he was there. Their dispiriting meeting and the poor and persecuted Jews he met in front of the synagogue and elsewhere in Moscow exposed Communism’s philosemitic lie.

On his return to England, Litvinoff started a newsletter that would later be called “Jews in Eastern Europe” and devoted himself to their liberation with indefatigable zeal for the next three decades. So much so that former Israeli ambassador to the US Meir Rosenne remarked that “many times, walking in the streets of Jerusalem and hearing Russian spoken by Jews who immigrated from the Soviet Union, I think to myself: Do they know that they owe their freedom to an unsung hero of our generation: Emanuel Litvinoff?”

American Jewish readers often take the great civic achievement of hyphenated Americanism for granted. They shouldn’t; there are no truly hyphenated Englishmen. It is perhaps partly for this reason that though Litvinoff went on to write some excellent novels, a transcendent memoir, and some of the best British television of his era, neither he nor Frederic Raphael, Alexander Baron, or any of their contemporaries ever made the splash of a Bellow, a Malamud, or a Roth. As the Anglo-Jewish writer Linda Grant would later have her heroine put it in the estimable When I Lived in Modern Times: “There was no contribution I could make to the forging of a national identity. It was fixed already, centuries ago.”

This returns us to Eliot, for it was nostalgia for the supposedly ethnically uniform post–Norman Conquest era in which English culture was formed that partly inspired his antisemitism. Its French equivalent drew him, unforgivably, to that loathsome medieval-fetishist, antisemite, and collaborator Charles Maurras, whose rightly shattered reputation Eliot sought to rehabilitate right to the end. Eliot’s own prelapsarian fantasy found its clearest expression in his 1933 lectures at the University of Virginia, later published—though, unlike his antisemitic poems, never republished—in After Strange Gods. The most malodorous of these lectures extolled the virtues of “blood kinship of ‘the same people living in the same place.’” In Eliot’s ideal society, “the population should be homogeneous,” and “reasons of race and religion combine[d] to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable.”

Litvinoff, a proud free-thinking Jew, was no Englishman, much to the benefit of his work, though he remained, despite all temptations, an English man, ending his days in Bloomsbury, barely a stone’s throw from Eliot’s old Faber offices. “I belonged to them a little and they belonged to me,” he wrote of his neighboring Englishmen, “yet they would have probably been puzzled to learn that I felt in some ways an outsider having more in common with certain people in New York, Tel Aviv or Moscow than themselves.”

“To T. S. Eliot” was included in Notes for a Survivor, a lovely little 1973 pamphlet-sized collection of those of his poems unified by their concern with his fellow Jews. Its ultraslim size means I must keep it pulled out in the Litvinoff section of my bookshelf, so that I don’t forget that it’s there.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Let My People Go

Many of the heroes of the Soviet Jewry movement have been unsung, until now.

Journeys Without End

For some three decades Lionel and Diana Trilling shared a limelight that was not quite identical but never entirely separate.

Light and Darkness

A great novelist and close reader of Calvin, , Marilynne Robinson has now written a luminous commentary on Genesis.. But is her God more predictable than the God of Abraham?

The Most Important Word in the World

For a moment, a literary giant and talmudic genius sparred over the implications of a biblical phrase.

David Rosen

How I love to read an article in which I learn something new from everything in it! Of course, it was always impossible for a Jewish English student—or anyone else?— to read Eliot without knowing that he was an anti-Semite; but I was unacquainted with its ignoble depths in him

More important, the article acquainted me with the work—and dramatic day—of Mr. Litvinoff. This article, and the Litvinoff poem, ought to be assigned as part of any class on Eliot. (Provided we haven’t yet been deprived of such classes).

My only disappointment was scrolling up, at the end of the review, to see the name of The Selected Works—of Litvinoff—and finding nothing. Perhaps this will be corrected someday.