Bellow after Gaza: Rereading To Jerusalem and Back

The real Jerusalem syndrome isn’t the one your tour guide told you about. It’s what Saul Bellow experienced on his 1975 trip. “When I came to Jerusalem I thought to take it easy,” he writes in To Jerusalem and Back. “But no one takes it easy here.” He wrote to a friend, “My intention was to wander about the Old City and sit contemplatively in the gardens and churches. But it is impossible in Jerusalem to detach oneself from the frightful political problems of Israel. I found myself ‘doing something.’”

What he did was listen—and seek out people worth listening to. “Here in Jerusalem,” writes Bellow, “when you shut your apartment door behind you you fall into a gale of conversation—exposition, argument, harangue, analysis, theory, expostulation, threat, and prophecy.” Everyone is a diplomat, but no one will be diplomatic. “The subject of all this talk is, ultimately, survival,” Bellow writes, “the survival of the decent society created in Israel within a few decades. At first this is hard to grasp because the setting is so civilized.”

This may be part of what attracted Bellow, the lifelong anthropology student, to Israel: Civilization was both so deep and so precarious. The bloody borders were so close. It is still true: It feels so normal in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, says the solidarity tourist after October 7. Flying back and forth to Israel during this past year of war, I found myself revisiting Bellow’s literary-political travelogue for its evocation of a distant yet unsettlingly familiar political world, for its insight and its blind spots, and always for its marvelous descriptions and flashes of wit.

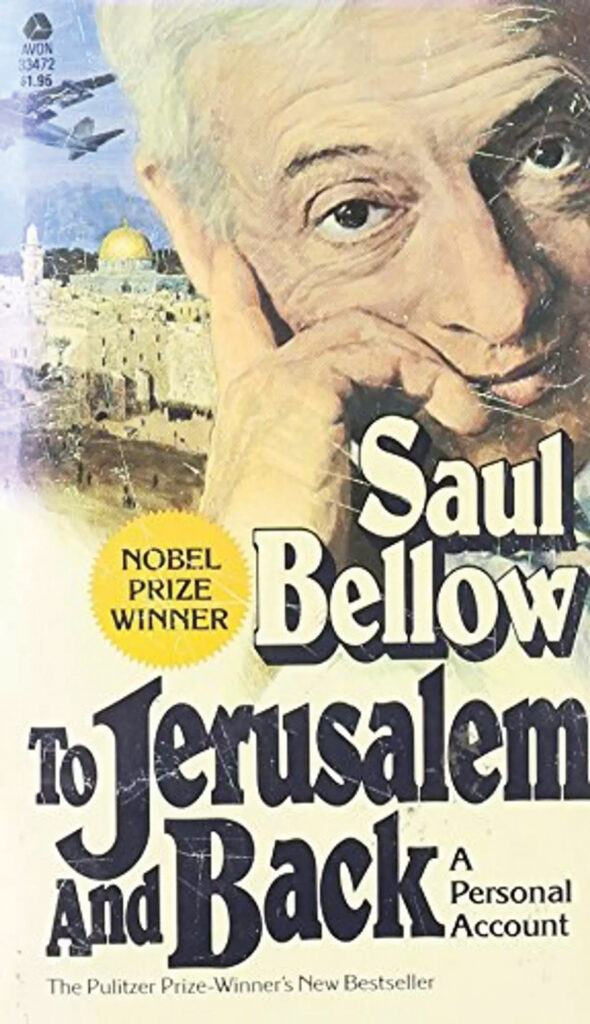

Bellow’s only foray into full-length nonfiction, To Jerusalem and Back was published in 1976, three years after the Yom Kippur War and shortly before he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The book “may well have clinched it,” writes biographer James Atlas. Here, Bellow the writer of ideas “grappled manfully with global politics”—and, I would add, permits himself to gape at the nation for which such grappling is everyday life.

Rather than play the Professor Luftmensch of many of his novels, Bellow is now merely a diligent student. “I don’t think my judgment has much value,” he tells a friend who asks for it. “I am simply an interested amateur—a learner. I can, however, tell him what I have heard from intelligent and experienced observers.” It’s a useful pose as he reads or meets with this or that professor.

It becomes harder to maintain, however, as he lands meetings with novelist A. B. Yehoshua, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, while Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek plays host. Abba Eban is described as “a type with which I am completely familiar.” Bellow is not the man on the Clapham omnibus. He is comfortable in this rarefied world of diplomats and deep thinkers and content at last to let the subject of his inquiry, Israel, take center stage.

So fascinating are the Israeli characters we meet and so urgent are the ideas they thrash about in Bellow’s quick tableaus, that even the reflective interludes among civilizational treasures can seem almost prelapsarian and out of place. Bellow felt some of this himself:

In these days of armored attacks on Yom Kippur, of Vietnams, Watergates, Mansons, Amins, terrorist massacres at Olympic Games, what are illuminated manuscripts, what are masterpieces of wrought iron, what are holy places?

Defeat had been staved off in the Yom Kippur War, but at great cost. Another round of fighting was expected with the Arab clients of the Soviet Union, but no one could say when. “Israel’s political leaders do not seem to me to be awake,” and few Israelis would have argued. All recognized that “American foreign policy is in retreat,” but Israel’s dependence on America had been made “cruelly explicit,” and Kissinger was demanding territorial concessions.

“There are few families in Israel that have not lost sons in the wars,” Bellow writes. “One does not make casual political conversations here.” Repeating the political complaints of Mahmud Abu Zuluf, the editor of Jerusalem’s Al-Quds daily, Bellow irritates his friend, the writer David Shahar, “with my American evenhandedness, my objectivity at his expense. It is so easy for outsiders to say that there are two sides to the question. What a terrible expression! I am beginning to detest it.”

Shahar does too:

“They don’t want our peace proposals. They don’t want concessions, they want us destroyed!” Shahar shouts and slams the table. “You don’t know them. The West doesn’t know them. They will not let us live. We must fight for our lives.”

It is a speech, captured perfectly, that all of us have heard and some of us have given—though Shahar, a distinguished novelist who was born in Jerusalem in the 1920s and fought for the Irgun, was more qualified than most to do so. But it isn’t Bellow’s speech. What troubles him is that he has no response to it:

As for me, I say no more. Can I tell Shahar that the “conscience of the West” will never permit Israel to be destroyed? I can say no such thing. Such grand statements are no longer made; all our hyperbole is nowadays reserved for silence. We know that anything can happen.

Domestic critics are eager to put Israel on trial. “Professor Tzvi Lamm of the Hebrew University charges that Israel has lost touch with reality.” He calls Israel autistic. A novelist Bellow meets “is convinced that Israel has sinned too much, that it has become too corrupt, and that it has lost its moral capital and has nothing to fight with.”

Bellow listens and finds many sins to worry about. Always fascinated by the primitive, he expects Israel to be civilized:

But at this uneasy hour the civilized world seems tired of its civilization, and tired also of the Jews. It wants to hear no more about survival. But there are the Jews, again at the edge of annihilation and as insistent as ever, demanding to know what the conscience of the world intends to do.

Bellow is more comfortable letting others prosecute the case against the Arabs. Where he must speak in his own words is against their apologists in the West. The French are the worst. “Since 1973, Le Monde has openly taken the side of the Arabs in their struggle with Israel,” he writes. “It supports terrorists. It is friendlier to Amin than to Rabin. A recent review of the autobiography of a fedayeen speaks of the Israelis as colonialist.” One is surprised again and again how little has changed in fifty years.

Before Israel’s rescue mission at Entebbe, Le Monde toasted Idi Amin’s triumph:

After the raid, Israel was accused of giving comfort to the reactionaries of Rhodesia and South Africa by its demonstration of military superiority and its use of Western arms and techniques, upsetting the balance between poor and rich countries, disturbing the work of men of good will in Paris who were trying to create a new climate and to treat the countries of the Third World as equals and partners.

Readers today will not be shocked to hear criticism of a successful Israeli hostage rescue. By now we are all familiar with the priorities of the Western left, which so dismayed Golda Meir.

Though Jean-Paul Sartre takes it on the chin in this book, it is Bellow’s depiction of The New York Times that stays with me:

“But don’t Americans know that Sadat was a Nazi?” the librarian says. Well, yes, well-informed people do have this information in their files. The New York Times is sure to have it, but the Times as I see it is a government within a government. It has a state department of its own, and its high councils have probably decided that it would be impolitic at this moment to call attention to Sadat’s admiration for Hitler.

Of the Times, he concludes, “If it covered ball games as badly as it reviews books, the fans would storm it like the Bastille.” In fairness, the Times had the decency to publish a positive review, by Irving Howe, of Bellow’s book.

Israel’s friends often harbor a secret hope for the world to forget all about it. We can understand some of the objections to Israeli-run Jerusalem from Muslims and even serious Christians. “Those who baffle me,” remarks Bellow, “are the disinterested parties, themselves without religious beliefs, calling for this that or the other form of shared control.” Why must they track Israel so relentlessly?

Bellow’s friend John Auerbach, a kibbutznik sailor-writer and an escapee from the Warsaw Ghetto who lost a son in war, wants to talk life and literature with Bellow, not politics. He tells of a young American sailor on shore leave, a boy from Oklahoma:

He had heard of Israel, but only just, and he was not especially interested. John was delighted by this. A clean young soul, he said. Such ignorance was refreshing. The young sailor knew nothing about holocausts or tanks in the desert or terrorist bombs.

Bellow allows us to see, if we read closely, the gentle critique behind his friend’s story. To Auerbach, what could Bellow, Chicago-raised, know about “holocausts or tanks in the desert or terrorist bombs”?

A trip to Jerusalem drives home to Bellow not necessarily how Jewish he is but how American. After listing some of the horrors going on around the world, he comments, “As an American, I can decide on any given day whether or not I wish to think of these abominations. I need not consider them. I can simply refuse to open the morning paper. In Israel, one has no such choice. There the violent total is added up every day.” The Israeli must track every development all over the world, for none will leave him untouched:

The world has been thrown into their arms and they are required to perform an incredible balancing act. Another way of putting it: no people has to work so hard on so many levels as this one. In less than thirty years the Israelis have produced a modern country—doorknobs and hinges, plumbing fixtures, electrical supplies, chamber music, airplanes, teacups. It is both a garrison state and a cultivated society. . . . All resources, all faculties are strained. Unremitting thought about the world situation parallels the defense effort. These people are actively, individually involved in universal history. I don’t see how they can bear it.

This thought recurs again and again. Yehoshua tells Bellow that in Israel one simply cannot write, because “you are continuously summoned to solidarity, summoned from within yourself rather than by any external compulsion; because you live from one newscast to the next.” Of Israel’s politicians, Bellow writes, “It is perhaps astonishing that they aren’t demented by the butcher problems, by the insensate pressure of crisis.”

If Israel were a brutish nation, as its enemies allege, it would be less remarkable, not more. The world has plenty of those, and they don’t detain us long. But in circumstances that engender brutes, Israel has strained to remain a thinking, building nation. It takes Bellow’s breath away.

Bellow praises Kollek’s efforts to serve Jerusalem’s Arabs but adds:

Still, I often think that Kollek wants to show the world, and especially the Arab world, what good sense and liberality can do. . . . The cruel history of this city can have a stop, he seems to be saying. He is, in this respect, less a psychologist than a rationalist: how can people fail to recognize their own interests? What a Jewish question that is!

The injustices of Israel’s founding prove less about Israel than about those who fixate on them. The “sin” of the Zionists, Bellow writes, summarizing the view of historian Walter Laqueur, “was that they behaved like other peoples. Nation-states have never come into existence peacefully and without injustices.”

Bellow devotes considerable thought to whether Jews have a duty to be better, to set a moral example. “Putative friends of Israel” are always saying so, and surely Jewish tradition says the same. In the end, Bellow concludes it’s the wrong question:

Obviously, the Jews accepted a historic responsibility to be exceptional. They have been held to this; they have held themselves to it. Now the question is whether more cannot be demanded from other peoples. On the others, no such demands are made. I sometimes wonder why it is impossible for Western intellectuals . . . to say to the Arabs, “We have to demand also more from you.”

It never works that way:

While Israel fought for life, debaters weighed her sins and especially the problem of the Palestinians. In this disorderly century refugees have fled from many countries. In India, in Africa, in Europe, millions of human beings have been put to flight, transported, enslaved, stampeded over the borders, left to starve, but only the case of the Palestinians is held permanently open. . . . What Switzerland is to winter holidays and the Dalmatian coast to summer tourists, Israel and the Palestinians are to the West’s need for justice—a sort of moral resort area.

Bellow’s instinct is to historicize. The Jews conquered the land? “Of course the Arabs had themselves come as conquerors, many centuries ago,” he writes. But he knows this doesn’t satiate. “It is manifestly true that others have displaced peasants from their lands. Nevertheless, the tu quoque argument is insufficient, and that there were injustices must be granted.”

Anyone who won’t grant that, he distrusts. But to a world that obsesses over it, he is defiant:

What others have done with a broad hand the Jews are accused of doing in a smaller way. The weaker you are, the more conspicuous your offenses; the more precarious your condition, the more hostile criticism you must expect.

After trenchant lines like this, I was surprised to learn that only two years after the book’s publication, Bellow signed an open letter expressing solidarity with the Israeli Peace Now movement. In The Life of Saul Bellow, biographer Zachary Leader writes:

That these were Bellow’s implicit positions in To Jerusalem and Back is suggested by the prominence he gives toward the end of the book to the views of Yehoshafat Harkabi in Israel . . . and of the sociologist Morris Janowitz back in Chicago.

On reflection, the book’s late turn in that direction doesn’t seem coincidental. This turn comes mostly as he winds his way back from Jerusalem to Chicago. He finds the liberal realism of Harkabi, the former hardline intelligence chief who would come to call himself a “Machiavellian dove,” and of the American liberal Zionist Janowitz more appealing than David Shahar’s unapologetic Israeli survivalism.

“The occupation is costly and embarrassing,” writes Bellow. “Israel, born out of a national liberation movement, now seems to be denying the Palestinians their political liberties.” Bellow admires Harkabi:

He concedes that the Arabs have been wronged, but he insists upon the moral meaning of Israel’s existence. Israel stands for something in Western history. . . . Arab refugees must be relieved and compensated, but Israel will not commit suicide for their sake. . . . A sweeping denial of Arab grievances is, however, an obstacle to peace.

The back and forth is dizzying, but it well illustrates how Bellow justifies the position he will carry forward in America. He will maintain that “the root of the problem is simply this—that the Arabs will not agree to the existence of Israel” but urge Israel to make concessions for its own sake. He attributes to Janowitz the view that “occupation of the West Bank makes it possible for the international community to blame Israel for everything that is wrong with the Middle East; occupation strengthens the Palestinian movement; occupation costs Israel a lot of money and brings it nothing but grief.” The argument is entirely familiar. And yet in our own day, we have seen that the absence of occupation—in Gaza and Southern Lebanon—can be even more expensive, in dollars, death, and grief.

Of the young Arabs who “make angry demonstrations, who throw the stones, challenge the occupation, and plant bombs,” Bellow writes, “they have their counterparts among the Israeli militants of the Gush Emunim movement,” religious Israelis settling the new territories. “Their settlements are held by some to imply a rejection of Zionism, for the Zionist pioneers were satisfied with a sanctuary and did not try to recover the Promised Land,” he adds. But the Zionist pioneers dreamed much bigger than he thinks, and the early settler movement, whatever its failings, was not equivalent to the Palestine Liberation Organization.

In the book’s final chapter, Bellow is delighted by a wire report of new Israeli proposals for peace talks. “These latest proposals will probably be ignored by the Arabs, but they indicate that Israel has not become immobile, inflexible, paralyzed by stubbornness of political rivals, or lacking in leadership,” he enthuses. Here we might ask why the proposals are such great news, so morally vindicating, if Bellow believes they will go nowhere? To him, peace proposals seem to prove that Israel still hasn’t buckled under the pressure of the “butcher problems” and still remains a thinking, sensitive society. But to whom does Israel have to prove itself—the biased international press that Bellow does so much to expose?

To Jerusalem and Back is deep and reflective, pragmatic and piercing. But it is notable, for a book published about Israel in 1976, that the name of Menachem Begin never appears. Begin’s 1977 election shook Israel, and his Likud party has governed for most of the years since. There are hints in the book that one could pick out to explain this phenomenon, but Bellow himself didn’t grasp them. And yet the canny novelist warned his readers of just such an oversight almost from the start, reflecting on a dinner with an archbishop in the opening pages:

I have been hearing conversations like this one for half a century. . . . Such intelligent discussions haven’t always been wrong. What is wrong with it is that the discussants invariably impart their own intelligence to what they are discussing. Later, historical studies show that what actually happened was devoid of anything like such intelligence.

Bellow repeatedly returns to this idea that we—the West, the Jews—have “an inordinate faith in the power of rationality,” to quote his friend Harkabi. And yet, as Bellow writes later in the book, “I am forced to consider whether Western Europe and the United States . . . do not go about lightly chloroformed.”

Suggested Reading

Letters From Chicago

One of the many pleasures of the recently published Saul Bellow: Letters is how it reacquaints us with Bellow's wry, poignant, infectiously erudite voice. This is all the more surprising because he wasn't, or at least so he insisted, a natural-born letter writer. As in his literature, Bellow's language is so stunning that one wonders whether he was writing to both his correspondents, and to readers like us.

Yehuda Amichai and the Jerusalem of the Middle

Yehuda Amichai's poetry brought angels and garbage collectors together on the streets of Jerusalem.

American Gods

One need not buy into the cultural importance of “Snapewives” to accept that the digital age is one in which individuals demand narratives, practices, and communities they find personally meaningful.

Paradox or Pluralism?

Walzer’s paradox of liberation, if that is what it is, is that religion is back, or that despite the extraordinary success of secularizing revolutionaries it never quite went away.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In