Memory and Terror

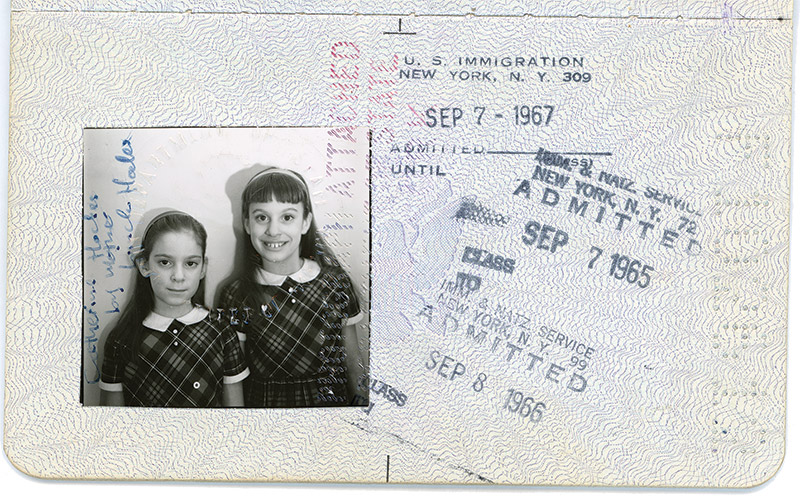

On September 6, 1970, twelve-year-old Martha Hodes was flying back, together with her thirteen-year-old sister, Catherine, from a summer vacation at their mother’s home in Tel Aviv to the New York City home of their father. Both of her parents were dancers, close students of Martha Graham, and both were now remarried to other dancers—in Linda Hodes’s case, an Israeli. What had brought Linda to live in Israel, however, was not matrimony or the reawakening of her very dormant Jewish identity or Zionism, but her profession. Living and working on temporary assignment teaching Graham’s works in Tel Aviv, she fell in love with and married a sabra named Ehud Ben-David. Her ex-husband retained custody of their two children.

The girls had the bad luck of returning to New York on TWA flight 741, one of four planes more or less simultaneously hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a radical Marxist-Leninist faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization led by George Habash. All told, the PFLP took more than four hundred hostages to use as bargaining chips for gaining the release of fellow terrorists then imprisoned in Britain, Switzerland, and Israel. The passengers were held captive for a week in the hijacked planes at “Revolution Airport” in the Jordanian desert, subject to terrible physical conditions and fearful uncertainty until they were freed through complex negotiations between the Palestinians, Britain, Switzerland, and the United States, with the International Committee of the Red Cross serving as facilitator.

For decades after her return home, Martha Hodes had repressed her memories of these events. But then, starting with 9/11, she found herself wanting to find out everything she could about what had happened to her in September 1970. Having become an award-winning historian and professor of nineteenth-century American history at New York University, she was equipped to do the necessary research:

With a scholar’s passion for evidence and accuracy, I wanted to compare recollections, compare documents, and compare recollections and documents with each other. As a hostage I had quelled memories and emotions; as a historian I wanted to search for facts and feelings, to provide meaning for everything that had happened to me and my family.

My Hijacking is thus a very personal story, often charming and poignant in its details. It provides glimpses of a unique childhood half a century ago in Tel Aviv, such as the weekend scene at the pool of Bethsabée de Rothschild—a real Rothschild, friend of Martha Graham, great patron of modern dance, and a pal of Martha’s mother and stepfather. “Ehud would throw us off his shoulders and perform outrageous dives that sent plumes of water onto my mother and the other dancers bronzing their bikini-clad bodies.” And it makes palpable the very different environment of a jet plane in the middle of the desert full of people who didn’t have enough water to drink and feared that their lives were in danger. There are lighter moments too. “‘What are you going to do now?’” a reporter calls out to Catherine after the hostages had reached safety in Amman. “‘Now I am going to thank God and have a bath,’ she says.” Her answer became the New York Times Quotation of the Day.

My Hijacking is, however, not just a personal but also a political story, one that endeavors to provide sympathetic insight into the experience of the victims of the hijacking but also the motivations and character of the perpetrators. After all her reading on the Middle East and Israel in preparation for the composition of this book (mapped out in her bibliography), Hodes has developed considerable respect for the PFLP—perhaps too much.

For one thing, Hodes carefully avoids referring to her captors as terrorists. Now, as we are often reminded, one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, but she doesn’t quite call them that either. Her preferred term is the one with which they flattered themselves: “commandos.” And she clearly looks favorably on their cause.

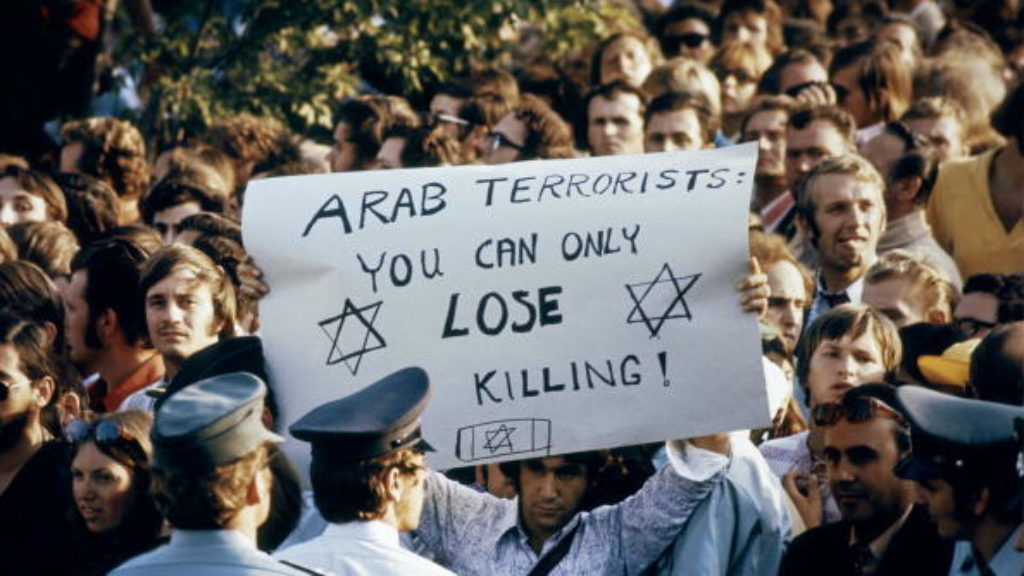

Before the hijacking, Hodes writes, she was quite ill informed. She had “never learned,” for instance, of the British and French carve-up of the Ottoman Empire during World War I and “of Britain’s 1917 Balfour Declaration, calling for Palestine to be ‘a national home for the Jewish people.’” She hadn’t known, as she puts it, that imperialists had seized land belonging mostly to Arabs and assigned it to the Jews. Nor was she acquainted with the “Palestinian narrative of a centuries-long homeland wrenched away by Zionists and the state of Israel, of Palestinians expelled, often violently, of villages destroyed, of homes and property appropriated for and by Jewish immigrants.” What she thinks she now knows makes it impossible for her to employ a pejorative term to describe the PFLP or, for that matter, the members of Black September, who perpetrated the massacre at the Summer Olympics in Munich in 1972. They, too, in Hodes’s eyes, are commandos.

Though she may now have more information than she did when she was twelve, Hodes still has a lot to learn about how Israel came into being. The Balfour Declaration did not, as she writes, call for Palestine to be a Jewish national home; it endorsed the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine, one in which “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” Before the creation of the State of Israel, the Zionist immigrants did not, as she claims, wrench a homeland away from the Palestinians (who had, indeed, never possessed one); they simply exercised their right (confirmed by the League of Nations) to settle among them—until the Palestinians themselves thwarted their efforts to do so. It was not a Zionist land grab that triggered the war that led to the suffering of so many Palestinians; it was the Palestinians’ and other Arabs’ unwillingness to accept the United Nations’ decision that the strife in Palestine required the establishment of a Jewish state alongside a Palestinian one. Had they not launched a war to prevent the implementation of the 1947 partition resolution, none of the Palestinians would have had to leave. Nor were all of the Palestinians who left what would become the State of Israel at this time actually expelled, as Benny Morris shows in The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, a book that Hodes includes in her bibliography but rarely cites.

Given her political outlook, it is not surprising that Hodes tends to present the PFLP terrorists in a positive light. She rarely disparages its members, instead referring to them as “genial” and “amiable” and emphasizing their kindness toward the children on the plane. She does acknowledge, however, that the commandos could be volatile, as when they subjected individual captives to intense interrogations; searched the hostages’ luggage and forced them to discard any items deemed to be Israeli in origin; brandished their weapons as they strode up and down the aisles of her plane; and openly wired the cockpit, presumably preparing it for detonation.

Hodes repeatedly denies that the hijackers were antisemitic. She challenges the claim, widely reported in the media, that they engaged in “selection” of Jewish passengers, pointing out that more than two-thirds of the fifty-four hostages on her plane who were detained when others were released were not Jewish. She concedes, however, that no Jews were among the captives taken from her plane to a hotel the first night, and “for some of the Jewish hostages, the events of [that] night only reinforced the idea of Palestinians as an incarnation of Nazis.” Hodes also denies that terrorists who referred to Israelis as “Jews” were displaying antisemitism on the grounds that, as Marxist-Leninists, they viewed Israelis as enemies only because they were colonizers, imperialists, and capitalists, not because they were Jewish. But, of course, the notion of Israel as an imperialist monster is itself a secular form of antisemitism—Jewish power and evil yet again. Moreover, the hijackings were part of a war against the Jewish state, and the planes targeted were not just randomly chosen but all departing from Israel and thus likely to include a disproportionate number of Jewish passengers—Jews who would constitute high-value bargaining chips against Israel.

While letting her captors off the hook when it comes to antisemitism, Hodes is quick to call out the prejudices of her fellow hostages. After the captive men and boys were removed from the plane, some of the women worried that they would be raped. Hodes retrospectively dismisses these fears as the product of stereotypical views of Arabs, not a logical response to the situational threat of being a kidnapped woman. The one time there was even a hint of potential sexual predation, she notes, the female captors dealt with it summarily. In fact, she uses this incident to praise the PFLP for allowing its female members to exert authority over its men when necessary.

Hodes is quick to acknowledge the terrorists’ version of their grievances and frequently recognizes their virtues as human beings. But what does she think of their actions in the events that affected her personally? Her extensive treatment of the captives’ suffering at the hands of the PFLP might well serve as a (not-so) silent indictment of the hijackers. She describes hardships ranging from the practical to the psychological. Along with inconsistent supplies of food and water, subjection to temperature extremes, and dysfunctional sanitation came extraordinary anxiety and fear—for Hodes herself (though she denied it at the time), for her fellow passengers, and for her parents and the relatives of other captives, who were helpless to intervene and thus forced to wait it out.

When Hodes does take up the moral and geopolitical issues at stake, she relies on a kind of ventriloquism, using her fellow captives to express certain views while effacing her own. She describes, for example, a debate between PFLP leader Bassam Abu-Sharif and one of the rabbis on board the plane over whether it was justifiable to inflict pain on so many noncombatant civilians. Her sole source for this exchange is Abu-Sharif’s 1995 book Best of Enemies, where he recalls, “‘Naturally, [the rabbi] was very much against the idea of taking innocent third parties to advance our cause.’” Although they never reached “‘any common ground,’” Abu-Sharif reports that he “‘enjoyed matching wits’” with the rabbi. According to Abu-Sharif, the rabbi told him that “in the Popular Front’s place, he would have done the same.” Here Hodes is paraphrasing Abu-Sharif, and she goes on to say that he “understood that any hostage might have said something similar, but he was nonetheless impressed that the rabbi said that at all.”

We have only Abu-Sharif’s report of the conversation; Hodes provides no direct evidence for what the rabbi may have actually said, nor does she name him specifically. His reported comments do, however, seem to be consistent with the prevailing strategy among the captives, which Hodes amply documents: that they should avoid provoking the hijackers, no matter what they thought of them. For at least some of the hostages, Hodes contends, this was not difficult. Over the course of their captivity, she, Catherine, and others “found themselves interested in the political cause of our captors,” with Catherine observing “others growing sensitive to their experiences.” A self-identified Zionist reported that he had “gained a measure of empathy” for the Palestinian refugees’ living conditions, while a stewardess became so sympathetic that she began wearing a PFLP button on her uniform. One of the few hostages who deviated from the group consensus was a courageous Arabic-speaking Jewish college student named Sarah Malka. Through frequent exchanges with the hijackers, she came to understand very well that the hostages’ lives were at risk, and she “made it her mission to dissuade [the hijackers] from causing harm. ‘You can win a revolution without blood on your hands,’” she told them.

It is not clear from Hodes’s account whether Malka agreed with the hijackers’ motivation but rejected their tactics, or exactly where Hodes herself stands with respect to the same issues. It is evident, however, that through her later research, she learned that in negotiations with officials representing the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Israel, the PFLP threatened to blow up the planes with the hostages on them if their demands were not met. Nonetheless, she appears unable to grasp the basic immorality of the PFLP’s strategy.

Interestingly, although her narrative makes the most of information recovered from her research in contemporary media, Hodes criticizes the news coverage, especially that produced in the US, for making a spectacle of the hijackings and distorting details for dramatic effect. She fails to mention that the same coverage inadvertently ended up giving the PFLP precisely the attention it was seeking as well as informing the public that dozens of American citizens, including many children like herself, were in grave peril.

Hodes’s account of the negotiations over the freeing of the hostages is cursory. Though she reports immersing herself in congressional, CIA, and State Department records, she does not appear to have looked at the files of the UN Security Council, which, after extensive deliberation, issued a sharp resolution denouncing the hijacking. She portrays the US and its allies unfavorably, characterizing the Americans as intransigent and the Israelis as making only a “grudging contribution” to the final resolution by agreeing to release two detained Algerians and ten imprisoned Lebanese—all of this while ignoring that it was the PFLP who had created the crisis in the first place.

Yes, the United States and Israel held out for some time before conceding to Palestinian demands, but it was the threat of military action by the US that made the deal a reality. As David Raab reports in his book Terror in Black September and US State Department documents support, President Richard Nixon ordered American aircraft carriers to move close to the coast of Lebanon, compelling the terrorists to realize that if they killed their captives, they, too, would be dead very soon. (Unlike the Islamists who succeeded them, the PFLP and other terrorists of this era were not suicidal.) Hodes does not seem to appreciate the decisive role that the United States government, along with Israel’s behind-the-scenes support for Jordan (which by that point was unwilling to continue hosting Palestinian refugees), played in ultimately freeing her and her fellow hostages.

When Hodes finally turns to the geopolitical implications of the event, she focuses only on how it affected the PFLP, not the broader Palestinian movement, Palestinian-Israeli relations, or the citizens of Israel—not to mention the subsequent lives of the civilians who had been captured. She fails to consider the consequences of “her” hijacking as one of multiple instances of terrorism, much of it lethal, carried out by the PFLP and kindred groups both before and after. Doing so would have compelled her to acknowledge that the PFLP’s success in 1970 served to embolden future terrorists. Instead, whether intentionally or not, she implicitly legitimates the terrorist practice of taking innocent civilians hostage to pressure governments into freeing accused or convicted criminals.

Toward the end, Hodes reports that in later years, several PFLP leaders retrospectively minimized their actions. Leila Khaled, one of the notorious Black September terrorists freed as a result of the negotiations, stated that she regretted the anguish caused by the hijacking (!), and Abu-Sharif went so far as to reject terrorism altogether—as if this somehow absolved them of their crimes. Hodes notes that the hijackers never faced criminal charges but leaves it at that; Raab, in contrast, describes in chilling detail the warm reception they and the freed Palestinian terrorist criminals (including Khaled) received when they arrived in Cairo.

If My Hijacking were a conventional history, Hodes’s reluctance to pass judgment might be regarded as admirable—assuming that she had provided a thorough and scrupulously balanced account of the hijacking and its context in the first place. Here, however, the biases and omissions in the historical sections, coupled with her refusal to denounce terrorism, imply that she believes the PFLP was justified in causing the suffering she and her fellow captives experienced, despite the fact that the hijackers clearly violated international law, any notion of just war, as well as widely accepted norms of humanitarianism. Hodes seems to be suggesting that the hostages’ week of suffering was nothing in comparison to the Palestinians’ prolonged ordeal as refugees, and the fact that the hostages ultimately survived absolved the PFLP of any criminality. To the extent that she assigns blame, it is to her parents, especially her mother, who made the decision to immigrate to Israel. “Without the hijacking,” she recalls musing at the time, “Catherine and I would already be home in New York with my father, which is where we would be if our parents had never gotten divorced, or even if they just lived in the same country.” No. Without the PFLP, there would have been no hijacking.

Hodes uses her self-defined genre “personal history” to gain considerable moral as well as intellectual latitude. Instead of writing as the sophisticated historian she has become, Hodes reverts repeatedly to her twelve-year-old self and what she knew and didn’t know, what she understood, at the time. She recalls her reaction to Abu-Sharif’s announcement to the passengers that he regretted the hijacking but believed it was necessary: “Unable to make sense of a history I do not know, I translate his words to myself only as We’re sorry to trouble you, but we hope you understand our point.” When her own research reveals that the hijackers were lying when they assured their captives they intended no bodily harm, she backs away from analysis, instead lapsing into her emotional state and claiming that the documents “feel remote from whatever fear may have come over me in the desert.”

Here and elsewhere, Hodes precludes deeper examination of her feelings by introjecting passages from Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, a copy of which her new stepfather had given her before she and her sister boarded their ill-fated flight in Tel Aviv. In this instance, she quotes the aviator’s question to the little prince, “Were you so sad, then?”

In the end, My Hijacking is no ordinary memoir but the work of a sharp-edged critical scholar who has had no compunctions about denouncing the racist and sexist practices of nineteenth-century white American slaveholders in her previous books. Unfortunately, she does not evince comparable moral clarity in her examination of a critical Middle Eastern event that caused her personal suffering and long-lasting trauma.

Why write such a book? Marco Roth, reviewing My Hijacking in Tablet, offers a partial explanation. After quoting a statement by Catherine to the Boston Phoenix that“‘the plea of any peoples to get back their homes is a valid plea. . . . Mistakes were made when these people were kicked out in the first place,’” he comments, “It is in places like these that My Hijacking also becomes a remarkable document of assimilated postwar American Jewish identity.” Roth does not fully explain what he means by this, but perhaps he is referring to the current leftist anti-Zionist position and how widely it has been adopted, especially by younger American Jews who are exposed to it at so many universities. This position entails, at least implicitly, the need to ignore negotiations and ententes as good-faith alternatives to terrorism and thus justifies hijacking, and worse. What Hodes lived through was not the Palestinian movement’s first use of terrorism, nor would it be the last. Their success in using hostages in 1970 to free fellow terrorists led to further acts of terrorism, even more lethal, including the Munich massacre two years later, which stands as further challenge to Hodes’s moral reticence.

Suggested Reading

Going Under with Klinghoffer

When it came to New York’s Metropolitan Opera this past fall The Death of Klinghoffer faced angry—and, it must be admitted, some pretty shrill—demonstrators.

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

I, Terrorist

Whither the great anti-American novel?

Twilight of the Anti-Semites

Nietzsche’s reception has been sharply divided between anti-Semitic and philo-Semitic readings. Richard C. Holub's new book explores how the philosopher's views changed over time and whether some of his statements about Jews should be attributed to another hand.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In