Of “Good Jews” and Bad Binaries

“The problem,” my daughter’s classmate at Cooper Union explained to her, “is not you.” They were heading out of painting class, where Darya had just presented her most recent work. In a response to the atrocities of October 7, she had made a series of paintings based on my wife’s childhood in Nahal Oz, which was one of the kibbutzim attacked by Hamas terrorists. In the classroom critique, several of my daughter’s classmates accused her of glorifying colonialism. The classmate continued to explain, patiently: “The problem is that there are so many Zionists on campus.”

My daughter’s classmate wanted to think the best of her and therefore took her, mistakenly, to be a “good Jew.” Why did he think this? Perhaps because of her otherwise progressive politics. Perhaps because she was his friend, and he took it for granted that a nice, educated human being would stridently oppose Israel, as he did.

What is the appropriate response to such a story? A father does not always know what to say. But then again, I’m not just a father; I’m also a teacher in the humanities. I’ve spent the past twenty-four years teaching classics at Stanford University, and I’m beginning to wonder whether my academic colleagues and I have done everything we could to educate our students. So it is perhaps worth stopping to explore, with some detachment, what it is that we are up against here.

At the most basic level, what my daughter’s classmate failed to perceive was that otherwise decent people could feel sympathy for Israelis—indeed support Israel in many ways—even while opposing certain Israeli policies. This was a blind spot in his conceptual apparatus. Arguably, there is an analogous blind spot in my own conceptual apparatus: I failed to notice, or at least to take seriously, that otherwise seemingly decent people might hate everything Israeli. Antisemitism alone won’t do to describe this phenomenon. We need a new category to begin making sense of this unsettling new environment in which we, especially those of us on college campuses, have found ourselves. I mean the discovery made, not on the morning of October 7, but in the afternoon, when—even while Israelis were still being shot in cold blood—college activists were already gathering signatures and drawing up signs blaming Israel. There have been many unpleasant revelations made since, on college campuses and beyond. But that Saturday afternoon already provided an important clarity: in the moral calculations of certain activists, Israeli suffering was almost entirely discounted.

The simplest, and I think correct, description of the situation is that this is a virulent form of anti-Israeli bigotry. Let me explain. The perennial observation that it is possible to criticize the Israeli government without being antisemitic is true. However, this equation misses something important, as such binaries often do. There is an attitude with regard to Israel and Israelis that is not a reasoned, specific critique but rather an expression of blind, broad-brush hatred. This hatred, in turn, is narrower than traditional antisemitism, since it targets only those Jews who are Israeli (and is sometimes expressed by Jews). I think it is worth regarding this bigotry as a specific form, distinct from (though of course not unrelated to) antisemitism. Its roots go to the heart of what we, as university educators, have failed to achieve over the last generation.

Now, to be clear, nothing would please an anti-Israeli bigot more than the affirmation that their specific bigotry is not identical to antisemitism. In this sense, the identification of anti-Israeliness might even be counterproductive. Antisemitism is taboo; anti-Israeli bigotry clearly is not. Which is precisely my point. The very notion of anti-Israeli bigotry would strike many people as a category error. Israelis, to many on the left, are simply not of the kind of people against whom a form of bigotry can be defined. To be clear, there is a way out: Israeli citizens can renounce Israel and then be readmitted to the circle of humanity (their conversion, of course, always remains suspect, and they must continuously reaffirm their anti-Zionism). But Israelis who waver in their condemnation of Israel are beyond the pale. To some people on the left, Israelis are uniquely disqualified from the bonds of empathy. To disqualify an entire group from the bonds of empathy is precisely what is meant by bigotry.

Some readers may object that those on the left who feel this way condemn Israel so thoroughly not because of blind hate but because of specific critiques. Indeed, to some, Israelis are anathematized because they are perceived as inherently alien to their land. This is taken to be a simple ontological fact about a certain space and a certain people. I understand where this sentiment comes from and will explain it shortly, but it should be stated immediately that this attitude, whereby certain people in certain lands essentially do not belong, is once again one of the oldest forms of bigotry. The attitude of others to Israel is rooted in a more detailed historical narrative in which Israel’s founders and their descendants have repeatedly engaged in nothing but acts of rapacious violence since the state’s inception. Such narratives should always put one on one’s guard. It is obvious to anyone with even a passing familiarity with history that reality is always more complex than that. This should be made clear: anti-Israeli bigots do not hate Israel because they believe the worst about its actions. To the contrary, they feel an urge to believe the worst about Israeli actions because they hate Israel.

It is easy not to be an anti-Israeli bigot. All you need to do is acknowledge that Israelis, too, have rights and that their aspirations should form a part—no more than a part, but no less—of the moral calculus of the Middle East. Indeed, this is so simple and obvious that one wonders why it is even worth pointing out; basic decency should suffice. It goes without saying—but I say it here—that the same must be acknowledged for Palestinians, and that to deny this is anti-Palestinian bigotry: a bigotry that certainly exists and needs to be resisted. This quarrel, however, does not take place on the academic left. The bigotry that we must confront in our own backyard is the one directed against Israelis.

Why does anti-Israeli bigotry exist? Why doesn’t basic decency rule it out? And more specifically, why is it so widespread among those who have ostensibly dedicated their lives to fighting bigotry? The facile response—“Oh, it’s just antisemitism”—misses the mark because the paradox is that anti-Israeli bigotry is often expressed by people who recognize and abhor antisemitism (indeed, not a few are Jewish themselves). To be fair, antisemitism itself is not easy to understand.

We humans have an urge to put things in neat categories—the neater the better, and best of all are simple binaries. Of course, such taxonomies never fit the world precisely; incongruities keep popping up and making us uncomfortable. As the anthropologist Mary Douglas famously argued, what we regard as dirty, disgusting, or dangerous is that which does not fit our categories: “matter out of place.” Indeed, this was how she explained the rules of kashrut and those of the book of Leviticus more generally. Certain animals didn’t fit the ancient Israelite taxonomy and were therefore considered a source of danger and contamination (pigs, for instance, share a cloven hoof with other large animals, such as cows, but do not chew their cuds). Whether or not this is correct as biblical interpretation, the principle is sound: humans are so invested in taxonomies that they sense danger and fear contamination when they are crossed or blurred.

This is an important context in which to consider antisemitism. Jews were often, perhaps always, a liminal group, failing to fit neatly into their societies’ categories, yet they remained internal and visible. In so doing, they breached the barrier between us and other. Note the subtle distinction: it’s not that Jews were the most other, because there were groups who were more alien and distant from the dominant culture. Jews, however, were other while simultaneously being near and familiar. This made them a source of danger and contamination. Disgust and hatred of Jews seems to have emerged, at least in part, from this unique sense of an uncanny, uncategorizable presence that had to be removed. Jews, for instance, read the same original scriptures but were not members of the same religion; they were inhabitants of modern European countries who were not quite European, and so on.

Religion and nationalism are not the only ideologies that seem to require overneat categories. Even the quest for universal, humanistic values is very often shaped by this desire. It is natural to try to impose a neat taxonomy of good and evil, right and wrong, upon a reality that—as realities do—resists easy definitions, especially on the margins. Israelis happen to occupy one of these margins. They are, in fact, hard to categorize as white or non-white, settler or indigenous, European or non-European. Hence, the blind unreasoning hatred.

To be clear: my claim is not that some people hate Israelis simply because they see Israelis as settler Europeans and that we should counter that by pointing out, say, that half of all Israeli Jews are of Middle Eastern origin; that they did not immigrate to Israel on behalf of a colonizing power; that Jewish history in, and longing for, this land extends back more than two thousand years, and so on. In fact, the opposite is true: some people hate Israelis precisely because Israelis resist these simple categorizations. The ambiguous position of Israelis as not quite settlers, yet not quite indigenous impinges on the very project—so central to some people’s identity—of categorizing the world this way. Hence the sense of the uncanny, the hatred, the disgust.

Of course, there is an irony here. Early Zionists, including Theodor Herzl, were ashamed of their liminal Jewish identity and sought to normalize it by becoming members of a nation like other nations. But the process of founding the Israeli nation-state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was, of necessity, a liminal process. The Jewish national liberation movement was entangled, inevitably and incongruously, in a colonial context. Upon becoming Israeli, Jewish liminality was not removed but rather transformed, which, in turn, gave rise to a new kind of hatred: anti-Israeli bigotry, a kind of descendant of antisemitism.

The Holocaust made antisemitism taboo; it would clearly take more than the murder and mayhem of October 7 to make anti-Israeli bigotry equally abhorred. And, of course, it is not as if antisemitism itself is irrelevant to our current predicament. The two hatreds often bleed into one another, and I am sure that many bigots who hate only Israel will sooner or later land on antisemitism. It’s so hard to tell the good Jews from the bad Jews. Why even bother?

And yet the recognition of anti-Israeli bigotry as a distinct form is worth the effort for at least two reasons. First, as noted, the simplifying binary of criticizing the government of Israel on one hand and antisemitism on the other creates a permission structure: many strident anti-Israelis look into their hearts and find no antisemitism and therefore conclude that their hate is legitimate. Recognizing the irrational source of their anti-Israelism may change at least a few minds. Difficult as it is, I do not want to give up on my daughter’s classmate (as a mishnah famously says, saving a single soul is like saving the whole world).

This brings me to my second and final point. We teachers in the humanities have allowed a whole generation of college students to be satisfied with simplistic historical and political binaries that do not do justice to—indeed falsify—human existence and lead to inhumane hatred. We must learn to do—and to teach—better.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Climate of Opinion

Academic scholars, of all people, should recognize that excoriation is not an acceptable substitute for argument, but, in fact, it pervades much of the discourse that today passes as “criticism of Israel.”

In My Country There Is Problem

Through this new book we get a disturbing picture of how students and faculty in the self-proclaimed progressive movement have demonized and marginalized Israel, its advocates, and anyone who wishes to genuinely learn about the Jewish State.

Welcome to the New Campus Normal: A Dispatch from Ohio State

"They found the graffiti in a stairwell. Protect Jewish Lives, only the words were crossed out by a red X." Yoshua G. B. Tolle reports on Jewish campus life amid rising antisemitism.

Strange, I’ve Seen that Face Before

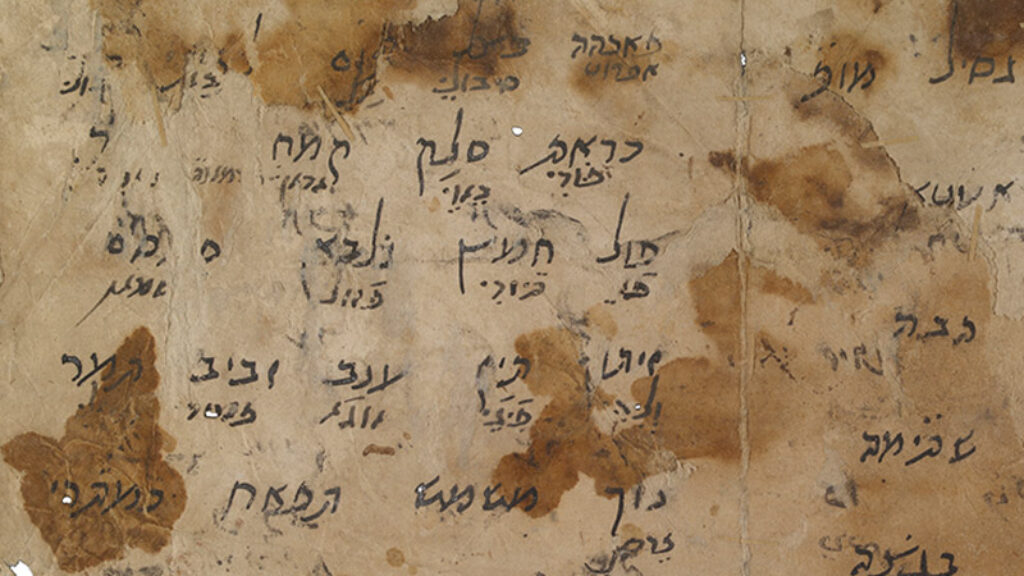

Just as I was about to close the window and move on to the next Geniza fragment, two words winked at me as if I were a friend.

gershon hepner

In his excellent article “Of ‘Good Jews’ and Bad Binaries,” in the winter 2024 Jewish Review of Books, Reviel Netz suggests that it is because Jews are considered by antisemites to be “out of place” that antisemites consider them to be disgusting. He draws on the Bible’s prohibition of the consumption of certain animals, and Mary Douglas’s opinion, originally attributed to Lord Chesterfield, that whatever is “out of place” is disgusting because being “out of place” makes it dirty. I would argue that an analysis of the biblical opposition to the consumption of pigs provides a deeper explanation for antisemitism.

Pigs are not “out of place” from a kashrut perspective because they have cloven hoofs; they are invalidated because they do not chew their cud. However, the Bible emphasizes that the consumption of pigs is prohibited because their cloven hoofs misleadingly makes them appear to not be “out of place.”

Lev. 11:7 explains the prohibition of pigs as follows:

And the pig, because it has true hoofs, with the hoofs cleft through, but does not chew the cud: it is impure for you.

The cause of antisemitism echoes the reason why the Bible singles out pigs as animals that are “out of place.” It is the fact that Jews’ external appearances resemble those of antisemites that causes antisemites to regard Jews as being “out of place.” Although Jews were never thought to have cloven hoofs, they were long thought to have horns, but what antisemites typically found most offensive about them is that they were able to hide their otherness.

Though Albert Baumgarten pointed out in an article on Mary Douglas’s “Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo,” that she eventually gave up the “out of place” explanation in its simplest form, it not only continues to be a valid explanation for antisemitism but is confirmed in the covenant Code, when it explains the what causes meat to be non-kosher. Exod. 22:30 states:

And you shall be holy people to Me: you must not eat meat that has become, in the field, treiphah, torn. you shall cast it to the dogs.

The primary reason why meat can become treiphah, violating the laws of kashrut, is by being “in the field,” which make it “out of place.” The problem of being “out of place” similarly affected Esau, as Gen. 25:27 explains:

When the boys grew up, Esau became a skillful hunter, a man of the field; but Jacob became a mild man, living in tents.

Esau sold his birthright to Jacob for a stew made of lentils, containing no meat that was “out of place” like him. Gen. 25:34 states:

And Jacob then gave Esau bread and lentil stew; and he ate and he drank, and he rose and went away. And Esau spurned the birthright.

The price that Jacob paid for the birthright he earned by avoiding meat that was “out of place” was being spurned by his brother, Esau, just as Jews are spurned by antisemites by trying to avoid what is “out of place.”