The Inklings

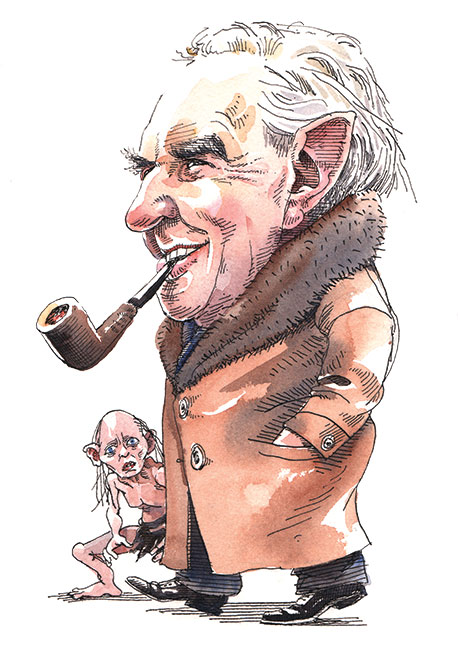

Had you the good fortune of being present at a gathering of the Inklings, you might have witnessed J. R. R. Tolkien reading from the cycle of private myths that would become The Lord of the Rings. (You might then have also heard fellow Inkling H. V. D. Dyson complaining “Oh God, not another [expletive] elf!”) Or you might have heard C. S. Lewis read from works-in-progress such as The Screwtape Letters, a satire in which a devil explains with withering perspicacity the weak points in the human soul, or Perelandra, a fantastical thought experiment that imagines the temptation of Eve on another planet. You might have heard a play by Owen Barfield, poetry by Charles Williams, a study of French history by Lewis’s brother Warnie, or other contributions by some of the 20 or so Christian writers, scholars, thinkers, and readers that met in various configurations from the 1930s to the 1950s to share writing, criticism, and conversation. By all accounts, you certainly would have heard laughter, passionate debate, the clink (when they met in their favorite Oxford pub) of beer glasses, and, despite the inevitable ebb and flow of friendships, the buzz of intellectual camaraderie.

As an example of literary and intellectual community, the group merits study on its own terms, yet the Inklings compel special interest because of Lewis and Tolkien, the two members who gave us Narnia and Middle Earth and who command the greatest attention from readers today. In different yet complementary ways the writings of Lewis and Tolkien offer a powerful challenge to the dominant assumptions of liberal modernity—relativism, scientism, materialism, historicism. More strikingly, they are the only such intellectual dissidents to have genuine purchase in popular culture. Leo Strauss may be as devastating as Lewis in his criticism of facile and destructive dogmas, but Hollywood isn’t planning a film version of Strauss’s Natural Right and History any time soon.

The Fellowship, Philip and Carol Zaleski’s chronicle of the Inklings, tries to straddle the group portrait and the Lewis-Tolkien focus, not always convincingly. Despite the quartet of names in the book’s subtitle, Barfield does not enter the story for a hundred pages, nor Williams for two hundred. And while the Zaleskis write that the Inklings’ “great hope was to restore Western culture to its religious roots, to unleash the powers of the imagination, to reenchant the world through Christian faith and pagan beauty,” this applies mainly to Lewis and Tolkien, who are described halfway into the book as “twin pillars, elevating the Inklings to greatness.”

Although everywhere amused by their subjects—their style is aggressively chummy—the Zaleskis are not worshipful devotees of Lewis and Tolkien. It is not merely that they deplore the “neomedieval affectations” of Tolkien’s style, find Screwtape’s “slaps” at its targets “tiresome,” and judge the crucial opening chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring to be a “last gasp of Hobbit silliness and facetiousness.” It is, more significantly, the equanimity signaled in their Foreword when they explain that, while the quartet on whom they focus are obvious choices as the best-known of the Inklings, they also offer a pleasing symmetry, “a perfect compass rose of faith,” ranging from the Catholic Tolkien and Anglican Lewis to the occultist Williams and anthroposophist Barfield. It is this equanimity about such irreconcilable approaches to fundamental questions of belief that makes The Fellowship generous to the point of being loosely agnostic.

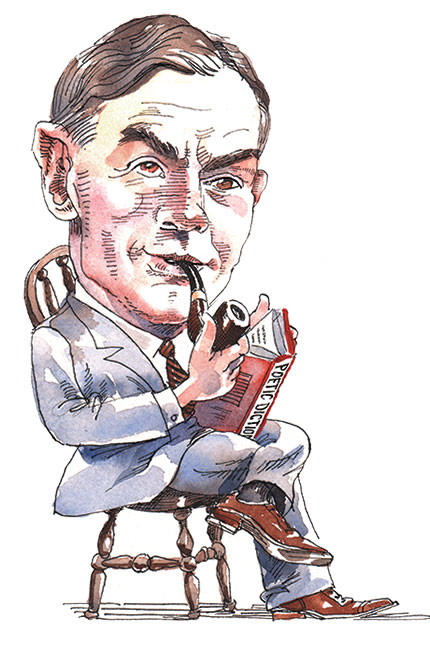

Lewis’s early friendship with Barfield, a lawyer, philosopher of language, and lifelong follower of the ideas of Rudolf Steiner, was certainly important for Lewis’s intellectual development. In his memoir Surprised by Joy, Lewis gladly admits that for all the seeming mumbo jumbo of Barfield’s anthroposophy, it provided a salutary counter-example to the barren materialism in which the young Lewis was mired before his ultimate turn to Christianity. More profoundly, Barfield’s developing philosophy of language suggested to Lewis and the other Inklings that the power of words themselves, the energy crackling in the experience of reading a poem, revealed a more than merely psychological dimension to human existence. Nevertheless, as the Zaleskis relate, these lessons absorbed, Lewis moved on from the early intensity of their friendship. Barfield eventually achieved his own measure of celebrity, mostly in the United States and in the context of the Aquarian 1960s, when his meditations on the evolution of human consciousness won admirers such as Saul Bellow.

Charles Williams, on the other hand, was interested in both faith and re-enchantment, but of a rather different sort than Lewis and Tolkien, as Grevel Lindop’s biography of the “third Inkling” shows. Despite its title, Lindop’s study allows Williams, untethered from Lewis and Tolkien, to bloom fascinatingly and darkly on his own terms. Captivating to all who knew him, Williams was an electrifying conversationalist and speaker. In the 1940s, without an advanced degree (his working-class family’s limited means prevented him from finishing university), he drew large and enthusiastic audiences to hear his discourses on Milton and Wordsworth.

Williams was also a member of secret societies such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and adhered to magical theories about the harnessing of sexual energy, mainly for the purpose of his poetic endeavors, and which were enacted in mildly sadomasochistic yet unconsummated relationships that the married Williams carried on throughout his life with a series of young women. A modernist poet of considerable achievement (and on close terms with T. S. Eliot), author of idiosyncratic works on Christian theology and witchcraft, a celebrated religious dramatist, and an influential editor at the Oxford University Press, Williams’s amazingly active life, cut short in his late 50s, repays examination both for its contradictions and for its counter-example to Inklings One and Two. While they enjoyed his company, Lewis and Tolkien, in response to someone who said that Williams ought to be burned at the stake for his heterodox views, both agreed that their friend was, in Lewis’s words, “eminently combustible.”

While Lindop makes a compelling case for renewed attention to Williams’ poetry, he is best-known today for his supernatural horror fiction. Lewis called his novel The Place of the Lion “one of the major literary events of my life,” although Tolkien found Williams’ novels “distasteful” and “ridiculous.” At their best, Williams’ potboilers are creepy fun, but they provide a foil, not a complement to the fantasies of Lewis and Tolkien. Unlike the latter, Williams’ thrust is theurgic, not mythic. His novels, which usually involve the irruption of some magical item into our own world—the Stone of Solomon, the original tarot deck, the Holy Grail, the Platonic forms as actual entities—observe with deft comic timing how his characters react to the state of affairs, but the stakes are less religious than talismanic (or even, at times, geopolitical, as when British acquisition of the Stone of Solomon threatens to trigger an Islamic uprising in the Middle East). With the possible exception of a few elements in Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, this is not what the twin pillars of the Inklings were up to.

Williams’ career also reminds us to what extent the Western esoteric tradition with which he was so fascinated is a jumbled, Christian imagination of things Jewish. Williams was not really given to anti-Semitism. The Jews in his novels range from the grotesque stereotype in his early War in Heaven to the saintly talmudic sages in Many Dimensions, but the point is usually that we Jews have magic stuff, Solomonic bric-a-brac. Slightly less instrumental was Williams’ fascination with Kabbalah, filtered through occult writer A. E. Waite. In one ritual with the Rosicrucian group of which Williams was a member he was apparently “raised on the cross of Tiphereth”—a typical mashing of Christian and Jewish symbols—while his poetic cycle Taliessin Through Logres reads at points as if T. S. Eliot had rendered portions of the Zohar with Arthurian knights in place of the sefirot.

For serious Jewish readers, though, it is Lewis and Tolkien who offer the most to contemplate, not least their emphasis on the centrality of the imagination in their fictions and their faith, not a topic on which normative Jewish thought has had very much to say. Readers of the Jewish Review of Books may remember that I broached this topic some years ago to some controversy (“Why There Is No Jewish Narnia,” Spring 2010). In part due to thoughtful criticism from Farah Mendlesohn and other scholars of fantasy literature, I no longer agree with all of my earlier formulations, though I think my question remains a good one. I remain certain, however, that in whatever direction a truly Jewish fantasyland may lie, we will at some point have to take our bearings by the twin pillars of the Inklings.

Suggested Reading

Temporary Measures: Sukkah City

The reimagining of an ancient architectural ritual.

Seeds of Subversion

The "Other" Jewish tradition.

Cognitive Dissonance

Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future. His proposal may surprise you.

Ireland and the Promised Land

Why isn’t Israel more like America, Jews from that country wonder. In his ambitious new book, Alexander Kaye instructively raises the question of why Israel isn’t even less like the United States.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In