The Lowells and the Jews

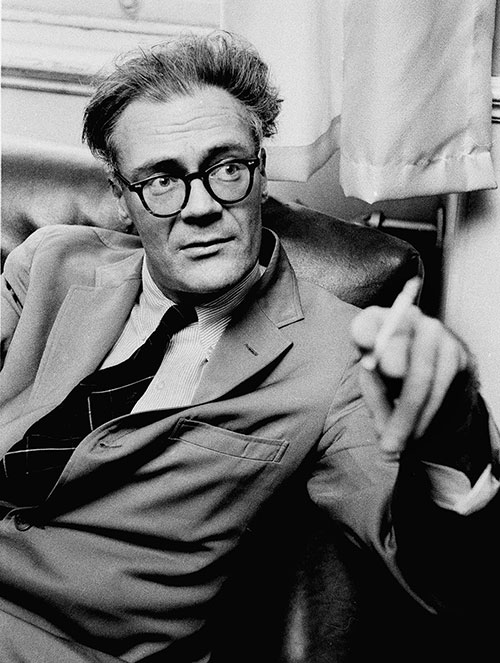

In 1979, Harvard’s literary magazine, the Advocate, ran a tribute by the poet Richard Tillinghast to his late mentor, entitled “Robert Lowell in the Sixties”:

I picture him at Harvard slouched in a leather chair, a penny loafer dangling from one foot, shoulders scrunched up toward his massive head—his hands framing a point in the air . . . one of many True cigarettes between his fingers.

That snapshot is spot on how I remember Lowell, the one time I ever saw him. He was holding court at a Friday night “Table Talk” at Harvard Hillel. Fall 1968 is my educated guess, senior year. He seemed in a good mood. I had no idea he was famously bipolar. He was on lithium then, between manic attacks, as I’ve now learned from Kay Redfield Jamison’s Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire, her exhaustive, empathetic account of a genius at war with himself. I remember not a word of what he said that night, save for one big thing: Robert Lowell, the most famous poet in America, icon of the antiwar movement, consummate Boston Brahmin, was especially glad to speak with a Jewish group because, he drawled, “I’m an eighth, you know.”

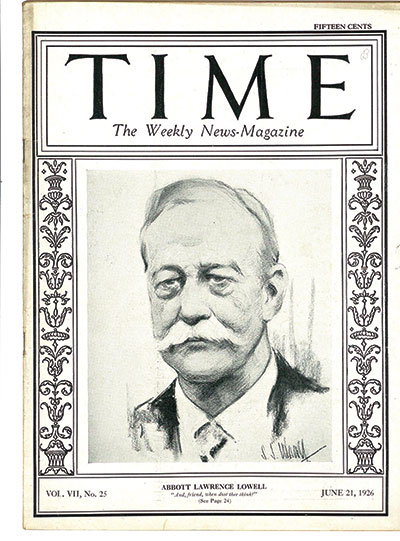

I was startled, delighted. Who knew? Montaigne, Cervantes, and now him too? And the delicious irony! For Harvard Jews, the name Lowell brings to mind the poet’s distant cousin, Abbott Lawrence Lowell (class of 1877), who tried to keep Jews from crashing the hallowed gates. Samuel Eliot Morison’s Three Centuries of Harvard (1936) provides a chart of 14 “Lowell Dynasty” alumni dating from Rev. John Lowell, class of 1721. A. Lawrence Lowell, a political scientist, was named president of Harvard in 1909. He believed in eugenics and Nordic superiority, and was a vice president of the Immigration Restriction League, founded in 1894 by three young Harvard graduates. The league’s efforts bore deadly fruit in 1924, when President Calvin Coolidge signed the Johnson–Reed Act, which barred the “golden door” to Jews later seeking refuge from Hitler’s Europe. In 1926, Lowell made the cover of Time, where he was lauded as an innovator. “The best type of liberal education in our complex modern world,” he was quoted, “aims at producing men who know a little of everything and something well.” No mention was made of his prejudice. Yet when he died at age 86 in 1943—a different era entirely—the obituary in Time told a fuller story:

He was roundly damned for protesting the appointment of Louis D. Brandeis to the U.S. Supreme Court for “lack of judicial temperament,” for proposing a quota for Jewish students at Harvard as an anti-anti-Semitic move during the Ku Klux rampage of 1922, for barring Negroes from freshman dormitories.

An “anti-anti-Semitic move”? That’s not the way it is remembered by Harvard Jews, but that’s how he saw it. In 1900, Jews made up 7 percent of Harvard’s entering class; by 1922, the figure was 22 percent. This influx of smart, ambitious Jews from immigrant families disconcerted Lowell. On June 17, 1922, the New York Times ran a story headed “Lowell Tells Jews Limit at Colleges Might Help Them.” It began with an indignant letter sent to Lowell by a Jewish attorney from Cleveland, Alfred Benesch (class of 1900), who invoked the names of Jacob Schiff and Felix Warburg, hinting that Jewish donors might withhold their largesse if a quota were imposed. Lowell replied that the proposed measures were good for the college and also for the Jews:

There is, most unfortunately, a rapidly growing anti-Semitic feeling in this country, causing—and no doubt in part caused by—a strong race feeling on the part of the Jews themselves. . . .

If every college in the country would take a limited proportion of Jews, I suspect we should go a long way toward eliminating race feeling among the students . . .

Benesch, in response, took offense at Lowell’s claim that Jewish “race feeling” was the cause of anti-Semitism. He pointed out that by Lowell’s logic, the way to eliminate anti-Semitism was to prohibit Jews entirely. In the event, the Harvard faculty rejected Lowell’s quota plan, but new admissions guidelines, which privileged the ambiguous categories of “character” and “fitness,” drove Jewish numbers below 15 percent by the 1930s.

Recent research has unearthed Lowell’s role in the “Secret Court” that hounded Harvard homosexuals in 1920. He also kept his distance from his flamboyantly mannish, cigar-smoking sister, who won a posthumous Pulitzer for her poetry in 1926. Still, Amy Lowell defended her older brother in a letter of 1922 to a Jewish friend, the poet and anthologist Louis Untermeyer:

You must not confuse my brother’s point of view with that of the extremists. He likes the Jews himself personally, as I do, but he feels very strongly that there should not be segregations of Americans into various racial strains. He is much averse to keeping Jews out of the college clubs and much averse to their forming Jew clubs on their own. He thinks they should all mix together and have no distinction . . .

Extremists in 1922 meant the Klan and Henry Ford, whose newspaper series “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem” had hundreds of thousands of readers each week. The Lowells were more subtle. “Private schools are excluding Jews, I believe,” Lowell cautioned Benesch, “and so, we know, are hotels.” Translation: Jewish alumni who don’t want Harvard to go that route had best acquiesce to a quota on Jews.

When I arrived in 1965, fresh from the Yeshivah of Flatbush, Harvard was again one-quarter Jewish. My dormitory was adjacent to Memorial Church, and the ringing of its two-and-a-half-ton bell (personally donated by A. Lawrence Lowell) would knock me from bed at 10 a.m. and propel me to Lowell Lecture Hall just in time to hear Robert Lowell’s close friend, the playwright William Alfred, recite Beowulf in his dazzling tour d’horizon of English lit. My senior thesis, supervised by the Brooklyn-born historian of immigration Oscar Handlin, dealt with status anxieties among New York’s Jewish elites in the late 19th century. Upon hearing Robert Lowell’s profession of Jewish ancestry, I rushed to Widener Library to consult Malcolm Stern’s Americans of Jewish Descent: A Compendium of Genealogy (1960). Sure enough, his father’s mother was a granddaughter of Major Mordecai Myers, born in 1776, the son of Jewish immigrants from Hungary and Austria.

Lowell House, majestically located on the banks of the Charles River, its tower boasting 17 bells purchased from a Russian monastery, was named for President Lowell. The future poet Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV, a 1935 graduate of St. Mark’s School, citadel of Boston privilege, went on to Harvard and lived in Lowell House. He enjoyed the company of Cousin Lawrence, by then retired. “Ours was an old family,” he told his future biographer, Ian Hamilton, in 1971:

It stood—just. Its last eminence was Lawrence, Amy’s brother, and president of Harvard for millennia, a grand fin de siècle president, a species long dead in America. He was cultured in the culture of 1900—very deaf, very sprightly, in his eighties. He was unique in our family for being able to read certain kinds of good poetry. I used to spend evenings with him, and go home to college at four in the morning.

All the same, Harvard didn’t suit Robert Lowell. He wrote poetry, but it was rejected by the Advocate. “Harvard didn’t mean so much to me,” he told a television interviewer in the 1960s. “I stayed there a year and a half.” He was bored, he explained: “I wanted some exemplar of modern poetry and couldn’t find one there.” He escaped to Nashville to study with the poets Allen Tate and John Crowe Ransom, then transferred to Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, where Ransom had joined the faculty, graduating in 1940. “I often doubt if I would have survived without you,” Lowell wrote Ransom many years later. In Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire, Kay Redfield Jamison describes Ransom as “the father and teacher he had desired but not had.”

Jamison’s book is not, she says, a biography but rather “a psychological account of the life and mind of Robert Lowell; it is as well a narrative of . . . [his] manic-depressive illness. . . . My interest lies in the entanglement of art, character, mood, and intellect.” Jamison, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, gained access to Lowell’s medical records, unlike previous biographers. She herself has struggled with manic depression, as she described two decades

ago in her acclaimed memoir An Unquiet Mind.

Jamison’s study of Lowell has been widely lauded by reviewers, and for good reason. Sandra Hochman’s recent memoir, Loving Robert Lowell, has been roundly ignored, also for good reason, though it does provide a different kind of insight. Her breathless story begins in 1961, when Hochman, 25, a budding poet, was sent by Encounter magazine to interview Lowell at the Russian Tea Room. He was 44 then, a lapsed convert to Catholicism, married to the Kentucky-born writer Elizabeth Hardwick. Hochman was separated from her Israeli violinist husband, who lived in Paris, and a passionate love affair ensued, ending badly. “The reason I am writing about him,” Hochman said in a recent Q & A with Foreword Reviews, “is because we had a beautiful relationship and because he’s so famous, people want to know as much as they can about him.” But the interview didn’t touch on what some people might want to know most: the Jewish angle. Hochman, a talented, troubled Jewish rich kid, brought out the Brahmin’s inner Jew. Loving Robert Lowell is a narcissistic, name-

dropping book, but touching too, and a rare window on Lowell’s need to be someone he was not. “I wish I was Jewish,” he told her. Hochman quotes—or paraphrases—Lowell as follows:

At Harvard, I was always on the fringes. . . . My father wrote a letter to me telling me I was not allowed to disgrace the Lowell family by leaving Harvard. My uncle Horace Lowell, a real anti-Semite if there ever was one, was president of Harvard, and I had to stay there.

Okay, so he wasn’t an uncle, and his name wasn’t Horace. Is this clear evidence of Hochman’s unreliability? Or a poetic hint that her memoir is true the way Lowell’s autobiographical poetry was true? “There’s a good deal of tinkering with fact,” as he told the Paris Review, and yet “there was always that standard of truth which you wouldn’t ordinarily have in poetry—the reader was to believe he was getting the real Robert Lowell.”

He was an only and unwanted child, rebellious, a prep school bully whose enduring nickname was “Cal,” short for Caligula. “It took Lowell’s parents most of his youth to recognize . . . [his] oppositional behavior,” writes Jamison, and that “the more tightly they tried to control him the more defiant he became.” They took him to his first psychiatrist at age 15. “He never was a natural child,” his mother Charlotte, a domineering woman of Mayflower stock, told one of his doctors.

While still at Harvard, Cal announced his plans to marry a young woman his parents deemed inappropriate. A fight ensued, and Lowell knocked his father Robert to the floor. Ian Hamilton, author of a widely read 1982 biography of Lowell, dwells with relish on this and myriad other outrageous episodes in his life. Jamison faults Hamilton for sensationalism, arguing that he missed the admirable, courageous Cal, who transmuted his destructive illness into great art. But she too misses a crucial element. Her authoritative, wordy book, eloquent and humane, ignores Lowell’s fascinating spark of Jewish identity. Still, amid her myriad renditions of the poet’s mental states is a one-liner that reverberates like a Harvard church bell: “From childhood, Lowell felt himself to be of a different tribe from his parents.” That’s what he was saying that night at Hillel.

Lowell’s mother died on a trip to Italy in 1954. Shortly thereafter he was hospitalized for mania for the fourth time (of 20) in his life. His doctors recommended he try writing his life story as therapy. Some of that output remained unpublished when he died, at age 60, in 1977. In a piece called “Near the Unbalanced Aquarium,” first published in 1987 in the New York Review of Books, he wrote:

I am writing my autobiography literally “to pass the time.” I almost doubt if the time would pass at all otherwise. However, I also hope the result will supply me with swaddling clothes, with a sort of immense bandage of grace and ambergris for my hurt nerves.

The brilliant result was Life Studies, which broke poetic ground in 1959 with its liberated technique and “confessional” content and won the National Book Award. “I wanted a style and rhythm that could say anything that conversation or prose could say,” he later explained. Flanked by 23 poems was the book’s centerpiece, “91 Revere Street,” a prose memoir of his boyhood home. It began and ended with a portrait of a Jew.

In 1986, the Times art critic John Russell reviewed a New York gallery show called American Paintings From the Toledo Museum of Art. “I could have done,” he sniffed, “without the portrait by William Morris Hunt in which a lugubrious old person called Francisca Paim da Terra Brum da Silveira is made to look like Dante in drag. . . . But there are also some wonderful surprises. I had never before heard of John Wesley Jarvis, but his portrait of Mordecai Myers, dated around 1813, looks as if Myers had stepped straight out of a novel by Stendhal.” Several copies existed of this portrait, and one of them hung at 91 Revere Street, Boston, on the border between Beacon Hill and immigrant Boston, where the future poet lived from 1924 until 1927. Lowell’s memoir begins:

The account of him is platitudinous, worldly and fond, but he has no Christian name and is entitled merely Major M. Myers in my Cousin Cassie Mason Myers Julian-James’s privately printed Biographical Sketches: A Key to a Cabinet of Heirlooms in the Smithsonian Museum. The name-plate under his portrait used to spell out his name bravely enough: he was Mordecai Myers. The artist painted Major Myers in his sanguine War of 1812 uniform with epaulets, white breeches, and a scarlet frogged waistcoat. His right hand played with the sword “now to be seen in the Smithsonian cabinet of heirlooms.” The pose was routine and gallant. The full-lipped smile was good-humoredly pompous and embarrassed.

A full facsimile of Cousin Cassie’s obscure book, published in 1908, is available online. Chapter One has a sepia version of the painting of M. Myers (no Christian name) in uniform. He was born in Newport, wrote Cassie, where his father was “a friend of the Reverend Ezra Styles [sic], afterward President of Yale College.” Lowell saw fit to quote those words verbatim, presumably for emphasis, perhaps with a knowing wink, since Stiles was a Puritan Hebraist who famously befriended Jews. M. Myers, Cassie wrote, was wounded in the War of 1812, served as a New York state assemblyman, and was later elected mayor of Schenectady. Lowell recounts these facts, but is more interested in the painting:

Undoubtedly Major Mordecai had lived in a more ritualistic, gaudy, and animal world than twentieth-century Boston. There was something undecided, Mediterranean, versatile, almost double-faced about his bearing which suggested that, even to his contemporaries, he must have seemed gratuitously both ci-devant and parvenu. He was a dark man, a German Jew—no downright Yankee, but maybe such a fellow as Napoleon’s mad, pomaded son-of-an-innkeeper-general, Junot, Duc D’Abrantes; a man like mad George III’s pomaded, disreputable son, “Prinny,” the Prince Regent. . . . Mordecai Myers was my Grandmother Lowell’s grandfather. His life was tame and honorable. . . . My mother was roused to warmth by the Major’s scarlet vest and exotic eye. . . . Great-great-Grandfather Mordecai! Poor sheepdog in wolf’s clothing! In the anarchy of my adolescent war on my parents, I tried to make him a true wolf, the wandering Jew! Homo lupus homini!

Myers appears here as both a has-been and an upstart. He’s perhaps a madman. But most of all, a wandering Jewish wolf, a weapon in the war against Lowell’s Brahmin parents. The Roman proverb Homo lupus homini means “man is wolf to man” and was quoted by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents.

“I’ve been gulping Freud and am a confused and slavish convert,” Lowell wrote Hardwick in 1953. Closely read, Lowell’s “91 Revere Street” is a small Freudian masterpiece. He writes of Lowell family snobbery, his mother’s disdain for his “unmasterful” father, her nagging him to leave the Navy for a better-paying civilian job. The mother is “roused to warmth” by the exotic Mordecai Myers, but not by her husband. Of his father, he wrote: “His opinions were almost morbidly hesitant, but he considered himself a matter-of-fact man of science and had an unspoiled faith in the superior efficiency of northern nations.” As Sandra Hochman puts it, unvarnished:

“So you were angry with your parents?” I asked Cal, looking into his beautiful cat’s eyes which had flecks of yellow. “Yes. Not only angry, but their mediocre minds and their philistine tastes, not to mention their prejudices against Jews and Negroes, made me sick.”

A scene from the penultimate page of “91 Revere Street” slyly celebrates Lowell’s Jewish heritage. The house is filled with Myers furnishings inherited from Cousin Cassie. The poet remembers:

When I shut my eyes to stop the sun, I saw first an orange disc, then a red disc, then the portrait of Major Myers apotheosized, as it were, by the sunlight lighting the blood smear of his scarlet waistcoat. . . . Great-great-Grandfather Myers had never frowned down in judgment on a Salem witch. There was no allegory in his eyes, no Mayflower. Instead he looked peacefully at his sideboard, his cut-glass decanters, his cellaret—the worldly bosom of the Mason-Myers mermaid engraved on a silver-plated urn. If he could have spoken, Mordecai would have said, “My children, my blood, accept graciously the loot of your inheritance. We are all dealers in used furniture.”

Here is how Jamison reads this pregnant passage: “Lowell contrasted the Puritan legacy left him by the early Lowells and Winslows with the lighter, more recent one of his great-great-grandfather Myers.” She does not mention that the apotheosized Myers was a Jew, which is why, of course, he never judged a Salem witch, or saw the world through Christian allegory—and dealt in used furniture.

But surely Lowell’s graciously accepted Jewish inheritance is a critical piece of his psychological furniture. “I’m one-eighth Jewish and seven-eighths non-Jewish,” he once told the Anglo-Jewish critic Al Alvarez. “The two thinkers, non-fictional thinkers, who influence and are never out of one’s mind are Marx and Freud.” Was that his “lighter” legacy?

Lowell’s “91 Revere Street” first appeared in the fall of 1956 in Partisan Review. By odd coincidence, that same October Edmund Wilson published an essay entitled “Notes on Gentile Pro-Semitism” in Commentary, another organ of the liberal Jewish intelligentsia:

The Gentile of American Puritan stock who puts himself in contact with the Hebrew culture finds something at once so alien that he has to make a special effort in order to adjust himself to it, and something that is perfectly familiar. The Puritanism of New England was a kind of new Judaism, a Judaism transposed in Anglo-Saxon terms. . . . When the Puritans came to America, they identified George III with Pharaoh and themselves with the Israelites in search of the Promised Land. . . . I have recently been collecting examples of the persistence through the 19th century of the New Englander’s deep-rooted conviction that the Jews are a special people.

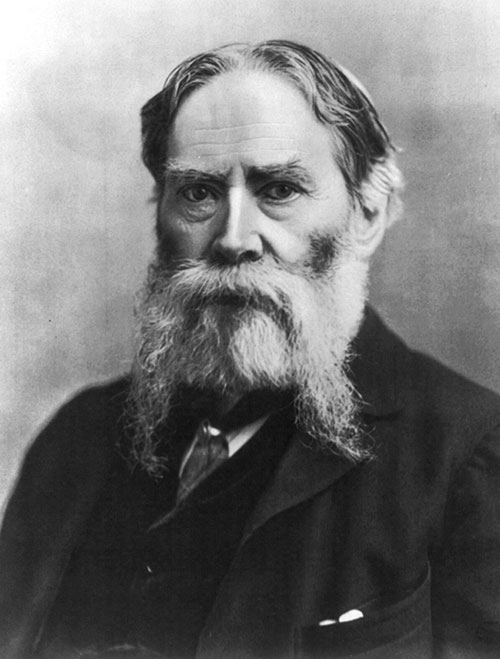

Robert Lowell was an heir to that mindset. Among Wilson’s New England case studies was his great-great-uncle James Russell Lowell, the distinguished 19th-century poet, abolitionist, and American ambassador to England. As we learn from Jamison, his mother, Harriet Brackett Spence Lowell, was incarcerated in 1845 at the McLean Asylum for the Insane near Boston, where her direct descendant Robert Lowell was hospitalized four times in the 1950s and 1960s. Wilson wrote in Commentary that James Russell Lowell had an “atavistic obsession” with Jews, a “mania on this subject.” His evidence was an unsigned piece in the Atlantic Monthly that reported an encounter with the ambassador in 1883:

He detected a Jew in every hiding-place and under every disguise, even when the fugitive had no suspicion of himself. To begin with nomenclature: all persons named for countries or towns are Jews; all with fantastic, compound names, such as Lilienthal, Morgenroth; all with names derived from colors, trades, animals, vegetables, minerals; all with Biblical names, except Puritan first names; all patronymics ending in son . . . In short, it appeared that this insidious race had penetrated and permeated the human family more universally than any other influence except original sin. He spoke of their talent and versatility, and of the numbers who had been illustrious in literature, the learned professions, art, science, and even war, until by degrees, from being shut out of society and every honorable and desirable pursuit, they had gained the prominent positions everywhere. . . . Finally he came to a stop, but not to a conclusion, and as no one else spoke, I said, “And when the Jews have got absolute control of finance, the army and navy, the press, diplomacy, society, titles, the government, and the earth’s surface, what do you suppose they will do with them—and with us?” “That,” he answered, turning towards me, and in a whisper audible to the whole table, “that is the question which will eventually drive me mad.”

“Though Lowell admired the Jews,” commented Wilson, “he conceived them as a power so formidable that they seemed on the verge of becoming a menace. In this vision of a world run entirely by Jews there is something of morbid suspicion, something of the state of mind that leads people to believe in the Protocols of Zion.” More than most, Wilson understood the treacherous interplay of anti-Semitism and its sneaky twin, philo.

Robert Lowell variously described his forebear as an “urbane man of letters,” a “spry deflater of the outsider”—e.g., Whitman and Mark Twain—and “a poet pedestalled for oblivion.” When Lowell spoke with the Paris Review at his home on Boston’s Marlborough Street, the interviewer, Frederick Seidel, noticed two portraits of poets on the walls of his study: the elder Lowell and a more notorious anti-Semite, Ezra Pound.

At age 19, Lowell had written Pound from Harvard, boldly requesting tutelage in Italy. “All my life I have been eccentric,” he began. “Your Cantos have re-created what I have imagined to be the blood of Homer.” Pound, an infamous fascist, made anti-American radio broadcasts from Mussolini’s Italy, for which he was locked up for treason. He spent 12 years at St. Elizabeths psychiatric hospital in Washington D.C., where Lowell visited him. But Pound’s Jewish conspiracy theories were more than Lowell could bear. As he wrote to him in 1956: “I love you, laugh with you, know you are a great poet . . . Still I have no mind for your gospel, and don’t let us talk about the Jews. I have several on my family tree, and . . . but let’s drop it.”

Lowell was obsessed with the Holocaust. In 1953, living in Amsterdam, he wrote the poet Randall Jarrell, a close friend from Kenyon days, that he had just read “twenty volumes of the Nuremberg trials,” as well as Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism. But Cal was also drawn to tyrants, and morbidly fixated on Hitler. According to Jamison, in the 1970s he read Mein Kampf aloud to his third wife, Caroline Blackwood, telling her that Hitler was a better writer than Melville. In his manic phases he sometimes believed he was Hitler, though at other times it was Napoleon, Alexander the Great, Homer’s Achilles, Dante, Shakespeare, Jesus Christ, or the “Jewish Messiah.”

Sandra Hochman’s memoir reveals Lowell’s chilling capacity to lurch from Jew-lover to the opposite. At his request, she made him a Seder. “He loved wearing the yarmulke I gave him. What the hell? Cal was now a Puritan, Boston Brahmin, lapsed Catholic, and Jew. In other words, a poet.” He promised to divorce his wife and marry her, but she didn’t know that this was a familiar pattern. Jamison links such manic affairs with Lowell’s yearning for rebirth and regeneration, noting that they were typically followed by hospitalization. At the climax of Hochman’s book, Cal throws a cocktail party at a friend’s town house. In attendance were Norman Mailer, William Styron, and W. H. Auden. Lowell drank too much champagne and announced their engagement. Then he started screaming that Stalin was worse than Hitler. Guests quickly began leaving, as if they “heard lightning and ran to avoid the storm.” Unlike Hochman, they all knew about his psychotic episodes. When everyone was gone, Lowell attacked her:

I could not believe what he was doing. He was clicking his heels like a Nazi and goose-stepping toward me. Cal lunged at my throat, throwing me down on the floor. . . . The angel was gone. Lucifer took the angel’s place . . . “I’m Hitler and you’re a Jew, and I’m going to kill you,” he said, putting his strong hands around my neck. I managed to lie still until he took his hands off my neck, and then he passed out. . . . For a terrible moment, I thought he was dead.

Did it happen? It certainly could have. He fought often with his first wife, the novelist Jean Stafford, and once tried to strangle her.

Following the Hochman affair Lowell was hospitalized for a month at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia for manic-depressive psychosis. He returned to Hardwick; they bought an apartment at 15 West 67th Street, and he commuted to teach at Harvard. “New York’s a much more exciting city than Boston,” he told V. S. Naipaul. “It’s a Jewish city: about a third of the city is Jewish and the talent is Jewish . . . Most of my friends are Jewish, and the people I’ve learned most from, and that I like best, in New York are Jewish. It’s quite strange that this tiny little minority should have such talent, and isn’t anyway typical of Jews, I think, through history.”

In 1963, Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil was panned in the pages of Commentary and Partisan Review. Lowell and Hardwick attended a soirée devoted to the controversy, presided over by Irving Howe. Lowell’s frank letter to his fellow poet Elizabeth Bishop exposes the limits of his philo-Semitism:

Hannah wasn’t there and most of the talk went against her. One was suddenly in a pure Jewish or Arabic world, people hardly speaking English, declaiming, confessing, orating in New Yorkese, in Yiddish, booing and clapping. . . . Well, it was alive, but very rash, cheap, declamatory etc. a sort of mixture of say Irish nationalists and an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting with contending sides.

But the day after “the little New York outburst,” he continued, the sides had met, and “there seemed to have been a catharsis, and everyone was friendly and relieved that what had been brewing for months had somehow boiled off. There’s nothing like the New York Jews. Odd that this is so, and that other American groups are so speechless and dead.”

In the fall of 1964, Lowell’s stage play The Old Glory, based on stories by his muses Hawthorne and Melville, opened in New York. To mark the occasion, Life magazine ran a long feature on the poet, from which two of his quotes stand out:

Jewishness, and not just of the New York variety, is the theme of today’s literature as the Middle West was the theme of Veblen’s time and the South in the Thirties. These regions have burnt out, and now we’re lucky to have the Jewish influence. It’s what keeps New York alive; not only writers and painters but also the good bourgeois who support the arts. . . .

Do I feel left out in a Jewish age? Not at all. Fortunately, I’m one-eighth Jewish myself, which I do feel is a saving grace. It’s not a lot of Jewish blood, but I think it would have been enough to come under the Nuremberg laws. My Jewish ancestors, oddly enough, were named Moses Mordecai and Mordecai Moses.

These lines cry out for commentary. Why the social scientist Thorstein Veblen and not a literary figure? I’m guessing that Lowell recalled Veblen’s famous essay of 1919, “The Intellectual Pre-Eminence of Jews in Modern Europe,” and identified with its thesis of Jewish excellence born of marginality. Why “Mordecai Moses” when the Lowell great-great-grandfather was actually named Mordecai Myers? And who’s this Moses Mordecai?

In a poem called “Searchings,” first published in Notebook 1967–68, he wrote: “I dreaming I was sailing a very small sailboat, / with my mother one-eighth Jewish, and her mother two-eighths, / down the Hudson, twice as wide as it is, wide as the Mississippi . . .” According to Malcolm Stern’s genealogy book (now updated and online), Moses Mordecai, son of Jacob and Rebecca, was born in New York in 1785. He moved to North Carolina, married Ann Willis Lane, and begat Margaret Mordecai, who married John Devereux, whose daughter Mary married the Mayflower descendant Arthur Winslow, Robert Lowell’s grandfather. Thus Lowell’s mother Charlotte Winslow was the great-granddaughter of Moses Mordecai, making her an eighth Jewish. So Robert Lowell was one-sixteenth Jewish on each side, an eighth in all. But to qualify for the Holocaust is a “saving grace”? Did he even meet the Nuremberg criteria? Technically, maybe not. But for the mad, genius poet, this “very small sailboat” on the Hudson was enough to keep him afloat on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

On June 2, 1967, Lowell made the cover of Time. “Something important and complex happens in the poetry of this complicated man,” opined the writer of the long profile. Meanwhile, his New York Jewish friends were mobilizing for Israel. On June 7, 1967, a major ad appeared in the Times, signed by 54 intellectual stars including Alfred Kazin, Irving Howe, and Robert Penn Warren, urging President Johnson to intervene and “maintain free passage” in the Gulf of Aqaba. Lowell had refused to add his name. “This war,” he told the Times, “should never have happened; for this Russia and America, the suppliers of weapons, are to blame.” Lowell’s biographer Ian Hamilton adds a telling tidbit: In a letter of June 4, 1967 to his Kenyon classmate, the Tennessee writer Peter Taylor, he wrote sardonically: “I am pretending my great-grandmother Deborah Mordecai was a Syrian belly dancer.” He took a different tone in a letter of June 14 to Elizabeth Bishop: “Did the late war scare you to death? It did me while it was simmering. We had a great wave of New York Jewish nationalism, all the doves turning into hawks. Well, my heart is in Israel, but it was a little like a blitz krieg [sic] against the Comanches—armed by Russia.”

Capable of violence, he was repelled by it. He had been jailed for draft refusal in 1943. His book Lord Weary’s Castle, for which he won a Pulitzer at age 30, included a poem called “At the Indian Killer’s Grave.” It was prefaced by a quote from Hawthorne, about “the veterans of King Philip’s War, who had burned villages and slaughtered young and old, with pious fierceness, while the godly souls throughout the land were helping them with prayer.” In the fall of 1967, Lowell was a central figure in the march on the Pentagon, chronicled by Norman Mailer in The Armies of the Night:

Robert Lowell gave off at times the unwilling haunted saintliness of a man who was repaying the moral debts of ten generations of ancestors. So his guilt must have been a tyrant of a chemical in his blood always ready to obliterate the best of his moods.

And then, in March 1969, he went to Israel. A few weeks prior to Lowell’s departure, Isaiah Berlin sent a long, anxious letter to his friend Yaacov Herzog, director general of the Israeli prime minister’s office. “I wonder who conceived this idea,” Berlin wrote from New York. “I saw Elie Wiesel yesterday, and he expressed extreme concern.” If not carefully planned, warned the Oxford philosopher, Lowell’s visit could be “grotesque”:

[A]s you must know, he goes off his head periodically in winter, and although he is a wonderfully clever, fascinating, touching, distinguished and in every way remarkable man . . . [he] is the hero of the anti-Vietnam movement now, so the usual mechanical treatment which is accorded to such visitors . . . will produce appalling results. Do not think I exaggerate, for I am not exaggerating. Can you do anything to stop the Foreign Office from attaching some mechanical young woman to him who will din the glories of the country into his ears patriotically, sincerely and disastrously? . . . I shall no doubt be here when he comes back, and I anticipate, if not the worst, certainly not the best—and remember that his most intimate friend in New York is Miss Arendt, whose view on Eichmann etc. he shares entirely.

Berlin urged that Lowell meet with “doubters and unorthodox persons” as well as poets, specifically recommending Gershom Scholem. “What he really needs is a left-wing kibbutz, or an army camp for a week, talking freely to simple boys and their commanders.” Jamison neglects the trip entirely, which is fairly astonishing: Not only was Lowell steeped in the Bible, he thought he might die in the Holy Land. He wrote Hardwick from Jerusalem on March 6, 1969:

Dearest a million miles away Liz:

I never knew I’d miss you so. You go around this queer indescribable country, [. . . from] armies I & 7 II [sic] pointed toward the Syrian & Jordanian borders, to a club of friends of Isaiah Berlin’s, to fooling [sic] utterly at home, Yiddish joking [with] a college president, to the failed Jewish English professor at Iowa in whose gentle hands I am—

But I have the shakes. . . . God, have mercy on me may I not die far from you! . . .

I’ll see a doctor in a few minutes. I only pray to God that I see you and Harriet again, dearest!

Three days later, he wrote again: “Dear Heart: . . . 4 days ago I went thru a trauma . . . Not so much trouble—just high blood pressure, trembling of foot and hand . . . Thrilling perplexing country—Hakeldama, the Field of Blood for always. . . . All my love, Cal.”

In Christian tradition, Hakeldama is the site in Jerusalem’s Valley of Hinnom where Judas Iscariot hanged himself, hence named “Field of Blood.” No wonder Lowell seized on the image. Did he set foot there? Ian Hamilton tells us next to nothing about his activities in Israel. Fittingly, the fullest account we have comes from a book of Hebrew poetry. The Jerusalem poet Harold Schimmel, born in New Jersey, educated at Cornell, made aliyah in 1962 and began writing in Hebrew. He had overlapped with Lowell in Boston and New York, and spent time with him in Israel. In 1986, he published Lowell, a book of 100 Hebrew sonnets in free verse, the last third of which are set in Israel. “You had a weakness for Jewish women,” Schimmel wrote, citing Sandra Hochman by name. At Kibbutz Ayelet Hashachar, gin and tonic in hand at 10:30 a.m., “You spoke of your ‘natural inclination to Jews.’” The Sea of Galilee: “‘How can it be so small?’” “In Sde Boker you visited BG”—the English letters appear in the Hebrew line—and discussed “Dayan and Golda,” history, and the Bible. Visits to Meah Shearim, Holy Sepulchre, Abu Ghosh, Nazareth. “Your secret refuge”: the Golden Chicken restaurant in East Jerusalem. A tour of the Israel Museum with Teddy Kollek. A dizzy spell at Masada. At a small gathering, “You pinched the poet / Lea Goldberg in the kitchen she complained about / the chutzpah of visiting gentiles who drink themselves silly . . .” Did that actually happen? It does sound like Lowell.

In early April 1969 Isaiah Berlin wrote from New York to an Oxford friend, Maurice Bowra: “Lowell has been to the Holy Land, and although it was anticipated that he would incline towards the Arabs on general left-wing grounds, he appears to have adored the Jews.” Lowell’s book History, published in 1973, bears out Berlin’s assessment. By then Lowell was living in London, divorced from the long-suffering Hardwick, and newly married to the beautiful, alcoholic Anglo-Irish writer and heiress Caroline Blackwood, whose previous husbands were Jews: the English painter Lucian Freud and

Israel Citkowitz, an American pianist and composer. History is arranged chronologically, beginning with the Bible: Adam and Eve, King David and Abishag, Solomon and his thousand wives. “Judith” manages to link the Holofernes story with “New York / where only Jews can write an English sentence, / the Jewish mother, half Jew, half anti-Jew, / says, literate, liberalize, liberate!” After the Bible come three sonnets called “Israel 1,” “Israel 2,” and “Israel 3,” which conflate antiquity and the modern Jewish State. In the first, he wrote: “The vagabond Alexander passed here, romero — /. . . This province, still provincial, prays to the one God / who left his footmark on the field of blood . . .”

In the second sonnet, he wrote:

The sun still burns in Israel. I could have stayed there

a month longer and even stood conscription,

though almost a pacifist, and still unsure

if Arabs are black . . . no Jew, and thirty years

too old. I loved the country, her briskness, danger,

jolting between salvation and demolition . . .

Since Moses, the long march over, saw the Mountain

lift its bullet-head past timberline to heaven:

the ways of Israel’s God are military . . .

“Jolting between salvation and demolition”—the manic-depressive core of the Israeli and Jewish story. How could a man like Robert Lowell not identify with the Jews? Recall Major Myers in his scarlet waistcoat and Lowell’s fascination with blood, his own not least. Think of him kindly in the end: a romero, a wandering Puritan pilgrim, one-eighth Jewish, in fitful pursuit of his promised land.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hebraic America

When Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin sat down to design the Great Seal of the United States they both turned to the Bible.

Our Challah Moment

America is having a challah moment that coincides with two food movements in popular culture.

Mysterious Mishnah

According to a midrash, God will tell the contending nations: “He who possesses my mystery—he is my son.” And when they ask “What is your mystery?” God will reply, “It is the Mishnah.” How do you translate a mystery?

Walking the Green Line

New books about the settlers and the settlements and depth and nuance to the discussions about their existence.

gershonhepner

YOU CANNOT KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT ANOTHER FELLOW

After James Atlas finished his biography of Bellow,

the writer asked him what he'd learned.

“That you can not know anything about another fellow,”

to which which the Nobel laureate replied,

in an opinion that can't be denied,

however often it is spurned,

by an enemy or fan,

“That will do young man.”

Those whom by analysis atempt our minds to mellow

can't faithfully be Grecian urned.

Though Robert Lowell's family included many nasty Harvard antisemites one of his grandsires

was a distinguished Jew of whom there is a critically-admired painting. He was Mordecai Myers.

[email protected]