Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Attack on Liberal Christian Bigotry and American Slavery

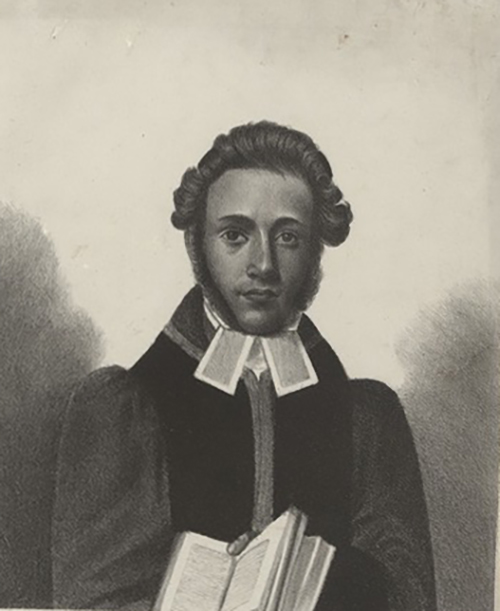

In 1840, Friedrich Wilhelm Krummacher, an Orthodox Protestant pastor from Elberfeld, Germany, delivered two sermons at his father’s liberal Protestant church. Krummacher used the New Testament texts of the “Last Judgement” (Matthew 25:31–46) and St. Paul’s curse against those who preach false gospels (Galatians 1:8–9) to denounce rationalists and modern Bible critics, saying, “It is not I who is cursing, no! Children, reflect, it is the apostle Paul who condemns you!” In response, one of Krummacher’s father’s liberal colleagues, Karl Friedrich Paniel, delivered three sermons defending rationalism and biblical criticism as expressing Christian values of tolerance and love. Most of the congregation sided with Paniel, but 22 pastors publicly declared themselves in support of Krummacher. An anonymous pamphlet then appeared attacking the 22 pastors from the left. The newspapers were abuzz, and the young Friedrich Engels contributed several articles on the controversy. Among those following the debate was the 33-year-old chief rabbi of nearby Oldenburg, Samson Raphael Hirsch.

Hirsch had risen to fame five years earlier when he anonymously published his Nineteen Letters on Judaism. Outlining a unique religious vision that aimed to synthesize the major Jewish ideologies of his age, Hirsch called himself a “man of no party,” but his work polarized his readers. Heinrich Graetz, a young yeshiva student destined to become the foremost 19th-century historian of the Jews, excitedly wrote Hirsch that his “divine letters” had melted the icy skepticism of his heart, while Abraham Geiger, the liberal pioneer of Reform Judaism, published a brutal review, despite having been friends with Hirsch at university.

Hirsch’s interest in a controversy between Protestants was not voyeuristic. Liberal Christian theologians such as the anonymous pamphleteer sought to draw a bright, invidious line between the Old and New Testaments, and hence between Judaism and Christianity. The God of the New Testament was, the pamphleteer argued, a rational, ethical God who preached universal love of humanity, while the God of the Old Testament was a tribal God who displayed his power through magic (as evidenced by Moses’s 10 plagues), permitted Jews to steal from Egyptians (Exodus 3:21–2), promoted genocide (Numbers 14:15), and put minute religious ceremonies on par with eternal laws of morality. (The pamphleteer was an educator and historian named Adolf Stahr, who would later marry the noted novelist and convert from Judaism Fanny Lewald.)

By contrast, the 22 pastors defended the Orthodox Lutheran doctrine that the Old and New Testaments were inseparable, asserting that Jesus and the Apostles recognized the Old Testament as holy and regarded it as the foundation upon which they built their teachings. The Old Testament’s God—and by implication, the God of the Jews—was the same as the New Testament’s: a unique, living, personal God.

In early 1841, Hirsch weighed in with his own anonymous, dramatic (and now nearly forgotten) response, which he signed “by a Jew.” Hirsch opened his broadside with an explanation for why he was jumping into a debate between Protestants. The Old Testament was, he wrote, “a sacred treasure that millions of people from near and far cling to with every fiber of their being.” Liberal Protestant biblical criticism did not reflect calm, unbiased scholarship. On the contrary, it was animated by an age-old anti-Jewish bigotry that should have been buried long ago: “It is high time for the non-Jewish thinker to set aside convenient pre-judgements and to begin to construct Christendom without having to destroy Judaism. It is high time to do justice to Judaism.”

Hirsch then asked his liberal Protestant readers to “open together your Bible and mine” and reread Genesis 1:27: “God created the human being in his image.” This foundational teaching of the Old Testament endowed all humanity with divine dignity, and any fair reading of it showed that it could not be conceived as “only directed at the Jewish tribe.” Hirsch then demonstrated how the Old Testament taught that while most of humanity was sunk in idolatry, Abraham, the patriarchs, and the later Israelites preached “the teachings of an all-loving, all-just unique God of humanity and consecrated themselves to this God through a life of sanctity, justice, and love with the goal of leading all humanity to return to this unique God.”

Hirsch noted the universal concern for humanity in the commandments that Moses later gave to the Jews, which included the injunctions: “You shall not oppress the stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9), and “If your brother becomes impoverished and his hand founders near you, you should support him, the stranger as well as the resident, for he lives near you” (Leviticus 25:35).

In his conclusion, Hirsch returned to the Jewish idea of one God, which his opponent had caricatured. Stahr had written:

It remains the eternal pride, the world historical honor of the Jewish people to have introduced God as one, and to have clung fast to this belief for millennia. But this is not the full truth, but only the first beginning. In the Old Testament, God is the exclusive God of Israel. In the New Testament, God is the God of all humanity.

Stahr concluded that “Christendom is tasked to convert a fanatical Judaism which stubbornly insists on maintaining isolation and conflict with other peoples and striving to annihilate them on the assumption that this is necessary to honor God.”

Hirsch challenged Stahr to search the pages of history and see who, in practice, had insisted upon conflict, trying to annihilate its opponents. Was it the Jews who persecuted as heretics the Donatists and the Arians? Did the Jews seek to exterminate the French Protestant Huguenots and execute the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre against them? Were the Jews protagonists in the bloody Thirty Years’ War between Catholics and Protestants? Did Jews enact the anti-Jewish edicts and persecutions throughout history? Hirsch concluded that far from purifying the Jewish teaching of the one God, Christians have failed to appreciate it fully. He put it like this:

The Jewish teaching of God’s unity has, through the salutary efforts of Christendom, redeemed the world from polytheism. But this is only a fragment, only the beginning of Judaism’s idea of God’s unity. For [Judaism teaches] the one and only God not just as an idea or conception. Rather, this idea is bound together with a wealth of consequences for human life. The idea of God’s unity is to be a guiding principle, the soul of the life of the individual and nation in all its relationships. The teaching is meant to infuse every part of one’s being and unfold in all aspects of one’s life. All the thoughts, enjoyments, words, and acts of an individual and people should be suffused by this teaching. . . . It is this side of Judaism with all its richness that has been least recognized in non-Jewish circles and which has mostly gone unrecognized.Until now, the idea of the unity of God that has entered into the life of people is only a fine beginning, and the full implementation of this idea into social life has scarcely begun.

As evidence of Christians’ failure to appreciate the full meaning of the Jewish teaching of the one God, Hirsch made a surprising turn to America, the “land of freedom” where white European Christians enslaved black people. He presented American slavery as of a piece with European Christians’ anti-Jewish discrimination:

For example, so long as Europeans persecute blacks in the land of freedom and equality, with whites hunting negroes (Negermenschen); so long as the United States, which famously prides itself on its freedom, robs people of human dignity and respect on the basis of the slightest difference in skin color; so long as the states which pride themselves on freedom find it possible to have lynching laws; so long as free cities close their walls, guilds, society, and deny human rights to even one Jew; so long as Jews are denied what every worm is allowed, namely to feed itself and build its domestic nest; so long as people have to bemoan the fact that they are denied what others are allowed, one should not yet boast greatly about “our times” and “our consciousness.” Our time has not yet learnt to actualize the first elements of the concept of the one God at all.

For Hirsch, Judaism’s teaching of God’s unity was not an abstract idea or dogma to be confessed. It was meant to animate one’s entire life, leading one to treat all human beings with dignity and love. Christians adopted the Jewish teaching of God’s unity as an idea, but most had not adopted it as a living principle. Otherwise, they could never countenance enslaving black people and imposing severe restrictions on Jews while claiming to be good Christians. Hirsch concluded that far from lecturing Jews on how they should be reforming their religion to bring it closer to Christianity, Christians have much to learn from Jews and Judaism.

Hirsch’s open denunciation of American slavery in 1841 contrasts with American Jews’ general reluctance to speak out about it before the Civil War. Those who did so were generally recent emigrants from Germany and central Europe who had become politicized by the democratic revolutions of 1848. As historian Bertram Korn noted, “Except for the teachings of a very few rabbis like David Einhorn of Baltimore, Judaism in America had not yet adopted a ‘social justice’ view of the responsibility of Jews towards society.” In 1841, it took an Orthodox rabbi from Germany, who was both further removed from American slavery and a more direct witness to antisemitism, to appreciate that black and Jewish civil rights were intimately connected.

Affirming the Old Testament’s unity and truth, Hirsch saw in Protestant Orthodoxy the basis for a universalist, ethical approach. By contrast, he saw in liberal Protestant Bible criticism, which denigrated the Old Testament and preached the New Testament’s superiority, a foundation for bigotry and discrimination.

Many Protestants in Oldenburg hailed Hirsch’s pamphlet. After his identity as its author was revealed, the Grand Duke of Oldenburg dispatched his adjutant-general to Hirsch’s home to congratulate him. Hirsch’s wife, Hannah Jüdel, later recounted that it became known that Hirsch had authored the pamphlet on a Friday, and so many Christian visitors came to their home that afternoon that she had to politely turn them away so she could light the Sabbath candles. Hirsch later recalled that of his many essays and writings, this was the one he had most enjoyed writing.

Thirteen years after the controversy, an anonymous pamphlet appeared in Frankfurt. It was written by a liberal rabbi, who accused the Israelite Religious Society, which Hirsch led, of being an Orthodox group that sought to “turn history’s wheel back” to a more primitive Judaism and of being a hate-filled “party of darkness” (Dunkelpartei). In his response titled “Religion Allied to Progress,” Hirsch explained that, while in principle, he was opposed to denominational labels, if pressed to do so, he would accept the title “Orthodox Jew.” In doing so, Hirsch implicitly aligned himself with Orthodox Protestants. He signed his essay “by a black” (von einem Schwarzen), playing on the idea that he was the leader of the “party of darkness” but perhaps also reminding his readers of his Orthodox Jewish identification with America’s enslaved black people.

Suggested Reading

Are We All Protestants Now?

Leora Batnitzky's new book charts the development of modern Jewish thought.

Emancipation and Its Discontents

How a small, marginal community of Moravian Jews grappled with the challenges modernization and secularization brought to European Jewry.

Pious Censorship

ArtScroll is not alone on Marc B. Shapiro’s hit list of haredi publishers and publications guilty of censorship and deliberate distortions.

Sincere Irony

In a new book about religious moderation, William Egginton makes some good points, along with a few immoderate claims.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In