“I am an Object Loved by God”: Rereading Clarice Lispector

In the fall of 1973, Clarice Lispector was working on her Sunday crônica (column) for Jornal do Brasil, one of Rio de Janeiro’s leading newspapers. “For as long as I’ve known myself,” she wrote, “social issues have been more important to me than anything else. In Recife the shantytowns were my first truth. Long before I felt ‘art,’ I felt the profound beauty of struggle.” She was describing the northeastern Brazilian city in whose impoverished Jewish community she had grown up during the 1920s and 30s. Although Lispector was one of Brazil’s most acclaimed writers, her article never made the paper. Instead, she was fired by the Jornal shortly after the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War in a purge of Jewish journalists.

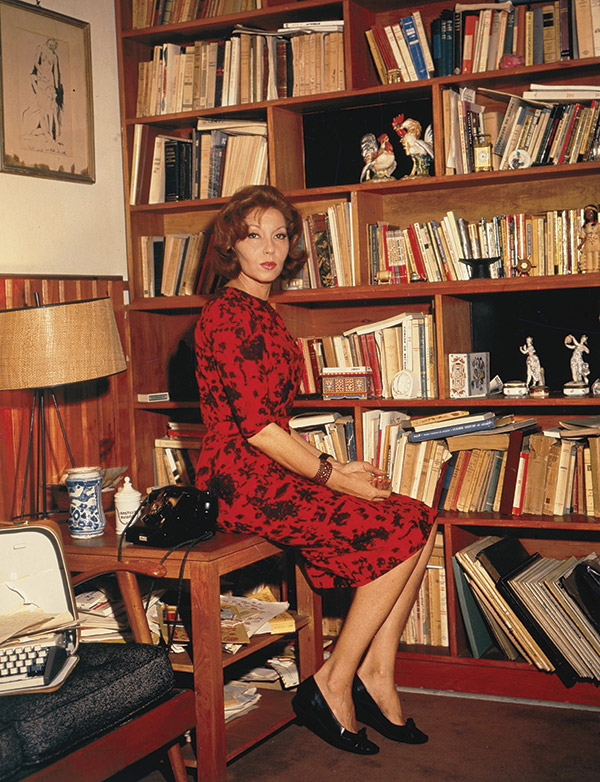

Barely known as Jewish in her time, Lispector is now regarded as perhaps Latin America’s greatest woman writer. In Brazil she has become such a cultural icon that her image often overshadows her actual writing: nine novels, ten short story collections, five children’s books, and six years of weekly columns. At bookstores, there are small altars built in her name, tote bags, and even coffee mugs with quotes that are often corny when shorn of their original literary contexts. (“I want vast distances. My savage intuition of myself.”) In iconic images, she (or the actresses who have played her) is often seen smoking and pensive, near a typewriter. Readers hailed her as a queen, a witch, a sorceress, a sphinx, and a feminine mystic without roots.Caetano Veloso, the icon of Tropicália music, serenaded her in a 1968 hit, asking, “What is Clarice’s mystery? What does she hold, so close to her heart?”

In her existentialist novels, she granted readers a rich, frank access to feminine consciousness and desire, as well as the social reality of Brazil. In The Passion According to G. H., for instance, a bourgeois woman is left alone in her apartment, and her secluded chamber becomes a mystical, delirious desert. (“I was being seduced,” the narrator claims. “And I was going toward that promising madness.”) The woman, G. H., whose acronym readers have understood to stand for “gênero humano,” meaning “human race,” descends into a complex ecstasy after her maid quits. Within her ontological loneliness, she fancies herself in the Middle East in ancient times. (“A night in Galilee is as if in the dark the breadth of the desert moved.”) But while this and her other novels usually dwelled on spiritual and mystical topics, she rarely mentioned Jews or acknowledged her own Jewishness.

Clarice was born Chaya Pinkhasova Lispektor in 1920 in Chechelnik, Podolia, in what is now Ukraine. Antisemitic violence, led by Ukrainian nationalists, drove the family to Romania, where her father finally managed to obtain a family passport. In 1922, they moved to Brazil to be close to relatives in Recife, in the state of Pernambuco—then, as now, one of the poorest regions of the country. Pinkhas became Pedro, Mania became Marieta, and Chaya became Clarice. Recife was one of the oldest Jewish communities in the New World (its Kahal Zur Israel synagogue was founded in 1636).

In Recife, Clarice and her sisters, Tania and Elisa, attended the Israelite School of Pernambuco, where they received lessons in Hebrew and Yiddish. According to the scholar Berta Waldman, it is most likely that Clarice spoke—perhaps read and wrote—Yiddish at home. Her mother, sick since before Lispector’s birth, wrote poetry and kept a diary, both in Yiddish. Her father subscribed to the Yiddish paper Der Tog, which was sent directly from New York City, studied traditional rabbinic texts, and led an active religious life.

Lispector’s English-language biographer, Benjamin Moser, claims that she wrote that seven was “her secret and kabbalistic number” and that her sister Tania confirmed she often read a “great deal of kabbalistic literature.” Certainly, from a young age Clarice thought that the number seven in particular held a strong power over her, and this later became a hidden motif in her work. In the short story “Preciousness,” a fifteen-year-old girl walks through a bombarded city and believes that an erotic encounter with two young men could reveal “the first of the seven mysteries that were so secret that only one thing was known about them: the number seven.” In “The Departure of the Train,” a woman in Rio de Janeiro feels chased by the same number: “The number seven followed her everywhere, it was her secret, her strength.” Lispector’s assistant, Olga Borrelli, recalled that when typing novels for her, Clarice would say: “Count seven, seven spaces between paragraphs, seven. Then, try not to go over thirteen pages.” Perhaps also mixing in some numerology from local Afro-Brazilian religions, she would superstitiously beg publishers to keep books under a certain number of pages. As a young girl, Clarice also thought that 1978 (1 + 9 + 7 + 8 = 25, and 2 + 5 = 7) was somehow her true kabbalistic year.

In 1935, five years after her mother’s death, the family moved to Rio de Janeiro, and their financial struggles overlapped with the struggles of assimilation into a city that is equal parts beautiful and gruesome. Lispector never quite denied her Jewish roots, although she more often than not distanced herself from them, and promoted a fanciful non-Jewish etymology for her surname: Lispector, she said, meant “lilies on the breast,” suggesting that “lis” came from “fleur-de-lis” and “pector” from the Latin “pectus.” (Other more plausible origins include the Ashkenazi name Spector, meaning teacher’s assistant, or lis-inspektor, Ukrainian for forest inspector, a common Jewish profession at that time.) Lispector’s ambivalence may also have been behind the story repeated by one of her close friends, who told Benjamin Moser that Clarice said her mother was raped by Russian soldiers, a non-Jewish origin story which he tends to support, despite the lack of any corroborating evidence.

In Rio, while quickly ascending to literary fame, she met and married a local lawyer named Maury Gurgel Valente, who later became a diplomat and with whom she traveled the world. She was briefly in Switzerland during World War II, where she wrote to her sisters that her Italian maid had remarked, “Some of these Swiss are so knowledgeable that they even look like Jews.” They then moved on to recently liberated Naples, where—under the protection of the Embassy—she volunteered with Brazilian troops while dining with other local expats.

When the war ended, Clarice expressed a sense of joy and a longing to return to Brazil, but no mention of the Holocaust or Jewish persecution appears in her works. In letters to her sisters, she said: “I bet that in Brazil the joy was greater. . . . The people here are so tired that no one felt really excited. . . . I was posing for De Chirico [the famous Italian painter] when a journalist screamed, ‘A guerra é finite!’ and I screamed with him. The painter stopped, commented on this strange form of joy, and kept on painting.”

Following her divorce and return to Brazil, Lispector wrote weekly crônicas at the Jornal do Brasil, between 1967 and 1973, under the supervision of editor Alberto Dines. Dines was a Zionist who had written several books on Stefan Zweig, the Austrian-Jewish writer who fled to, and later died in, Brazil. Dines was savvy when working around the dictatorship, and for many years he was able to dodge the strict censorship that affected media at the time.

Under Dines, some of Lispector’s crônicas veered away from travel and literature and touched on political topics. She addressed police brutality and the lack of social mobility in Brazil, and also participated in a famous protest against the dictatorship, the so-called March of the Hundred Thousand, alongside other major cultural figures such as the communist architect Oscar Niemeyer. On two occasions, she wrote about Israel. In 1968, she reviewed a book by the architect José Reznik, praising Reznik’s reading of Israeli architecture and wryly announcing that it was “excellent reading for the Christmas holidays.” In 1972, she mentioned her travels around the Mediterranean to Greece, Spain, Italy, and, finally, Israel. “I want to see how people live under different rules,” she wrote, but said nothing further.

But while Lispector was maintaining her customary aloofness, the political turmoil of the times caught up to her. All around Latin America, the need for oil led to countries like Argentina and Brazil embracing Arab countries and distancing themselves from Israel. In 1975, the Brazilian dictator, Ernesto Geisel, cosponsored United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379, which declared that Zionism was a form of racism. A few years later, he blocked the extradition of the infamous former Sobibor deputy commander Gustav Wagner, allowing him to die peacefully in São Paulo in 1980.

In 2006, Benjamin Moser interviewed Alberto Dines about the post–Yom Kippur purge at Jornal do Brasil. Apparently, the war in the Middle East had escalated tensions between the newspaper’s owner, Nascimento Brito, and its head editors. Before her next column ran, Lispector received a letter with the crônicas that were scheduled to be published in the weeks to come. “The paper ended up Judenrein,” Dines told Moser. “But they did it carefully enough that it wasn’t immediately obvious. They never said it, but the result was clear enough. Typically Brazilian.”

Lispector took up translating as a way to make up for the lost income from the Jornal do Brasil firing. She was heterodox in her choices. In her archives at Casa Rui de Barbosa, in Rio, you can see manuscripts of her translation of Yukio Mishima from the English translation into Portuguese and Hedda Gabler from “the Spanish, English and French.” But the most important translation project she took on was Bella Chagall’s memoir of her Lubavitcher childhood in Vitebsk, Burning Lights.

Clarice had always been an admirer of Bella’s husband Marc Chagall, even invoking him in her prose—in her novel An Apprenticeship or The Book of Pleasures, she describes the feeling of meeting a lover as “losing all the weight of her body like a figure from Chagall.” But Burning Lights was still a radical departure for her. The memoiris both a tribute to Bella Chagall’s Hasidic upbringing as well as a turn to Yiddish at a moment in her life when Chagall had almost forgotten her mother tongue. “A desire comes to me to write,” Chagall wrote in 1939, “and to write in my faltering mother tongue, which, as it happens, I have not spoken since I left the home of my parents.” (Lispector worked from the French translation by Chagall’s daughter, Ida, not the Yiddish original.)

Bella Chagall was born during Hanukkah in 1889, and Burning Lights is punctuated lovingly by Jewish holidays. In 1939, on the brink of catastrophe in Europe, her impulse was to return to her roots and her people’s god. Lispector’s decision, amid heightened antisemitism, to translate Chagall’s memoir of her Yiddish childhood into Portuguese seems to have also been a form of return. In 1976, she told an interviewer, “I am Jewish, you know, although I don’t believe that the Jewish people is the people chosen by God. . . . In the end, I am Brazilian, and that’s final, once and for all.”

At the time, Lispector was working on what would be her last book, a beautiful novella, The Hour of the Star.She dedicated the book “to the memory of my former poverty, when everything was more sober and dignified and I had never eaten lobster.” She closes the dedication with the remark that the work is “a story in Technicolor to add a little luxury which, by God, I need to. Amen for all of us.” The heroine of the novella, in the sole explicit reference to Jewish history in Lispector’s work, is named Macabéa.

But, unlike the Maccabees, Lispector’s Macabéa is a victim, not a hero. She is presented to us like “thousands of other girls . . . from the northeast . . . in the slums of Rio de Janeiro,” and not unlike Lispector herself. Her story is narrated in the cruel voice of a former lover who berates her as a virgin, an idiot, “scarcely a body.” Macabéa seems destined to oblivion and defeat: she attempts to make a life in the city, but it eats her alive. She falls in love with a man named, of all things, Olímpico de Jesus, but he is beyond cruel. In the background, a reader can still perceive a hint of Chagall-like images: “Only now do I understand and only now has the secret meaning sprouted: the violin is a warning. I know that when I die I’ll hear the man’s violin and demand music, music, music.” Finally, she visits a clairvoyant who promises her she will marry a rich German man named Hans. Instead, Macabéa is run over by a Mercedes-Benz.

Macabéa is an undeniably pathetic character, but her life is somehow surrounded by lights, by longing hope, by Chagall-esque fiddlers. “Pray for her,” the narrator implores at the end of this exquisite little book, “and may everyone stop what they’re doing to breathe life into her, since Macabéa for now is adrift in chaos like the door swinging in an infinite wind.”

In 1977, while in the final stage of ovarian cancer, Clarice scribbled a few lines about her last name, still imagining it as deriving from a romantic image in a Romance language:

I am an object loved by God. And that makes flowers blossom upon my breast. He created me in the same way I created the sentence I just wrote: “I am an object loved by God” and he enjoyed creating me as much as I enjoyed creating the phrase. And the more spirit the human object has, the greater is God’s satisfaction.

A little while later, on her deathbed, she asked for a kosher pickle.

Lispector died in December 1977, just days before the year that had always held some deep, kabbalistic meaning for her. She was buried in the Cementério Israelita in Rio de Janeiro. Under her Hebrew name—Chaya, daughter of Pinkhas—the epitaph on her grave is taken from her novel The Passion According to G. H.: “Holding someone’s hand was always my idea of joy.”

Suggested Reading

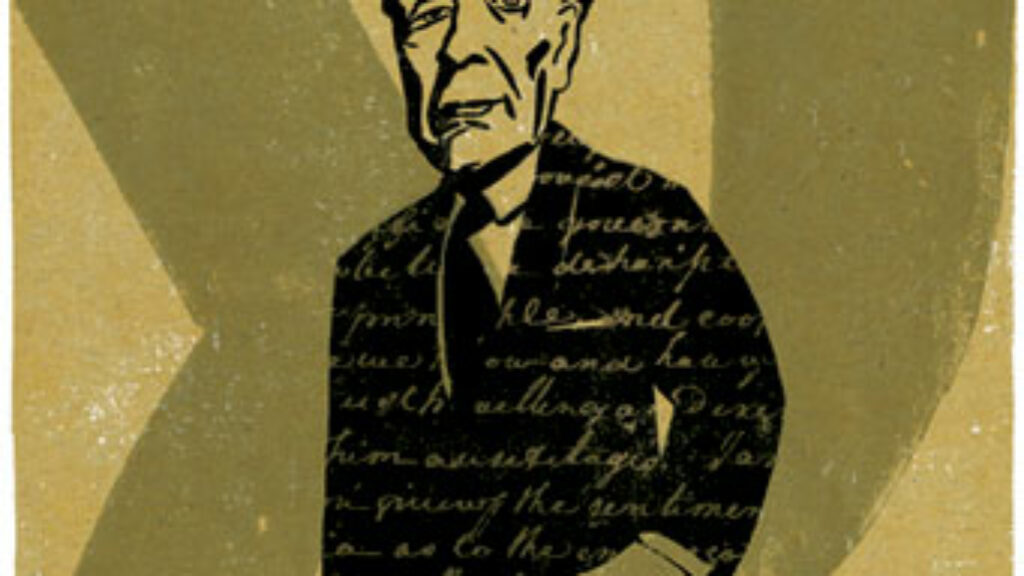

Borges, the Jew

Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentinian Nobel Prize-winning writer was captivated by Judaism. In 1934, he lamented, "hope is dimming that I will ever be able to discover my link to the Table of the Breads and the Sea of Bronze; to Heine, Gleizer, and the ten Sephiroth; to Ecclesiastes and Chaplin."

The Future Past Perfect

Treasure and tragedy in the letters of Stefan and Lotte Zweig, one of the most famous literary couples of the early 20th century.

A Golem in Argentina

When an indigenous Argentine woman falls in love with a golem, her grandmother creates a love potion to win the golem’s (perhaps non-existent?) heart. What could possibly go wrong?

Memory Palace

“Dust comes from something. It shows something has happened, shows what has been disturbed or changed in the world. It marks time,” Edmund de Waal writes to the long-dead Moïse de Camondo.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In