Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The late rabbi Jonathan Sacks held that lollipops were of crucial importance in the house of the Lord. “I want to be remembered,” he once remarked, “as the man who gave out sweets to children in shul.” Rabbi Sacks was hardly alone in his belief in the importance of candy in the synagogue experience. In 1947, a group of Zionist Socialists from the Freeland League went to Suriname to determine whether the small South American country would make a good home state for the Jews. As Adam L. Rovner documented in his In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands Before Israel, the resulting report “estimated how many professionals per thousand families would be necessary for the settlement project”:

The civil engineer . . . foresaw bustling hamlets of “milkmen” (five), “shoemakers” (four), “fishermen” (ten), “cinema operators” (three), “undergarment makers” (two), one “banana handler,” and one “rabbi.”. . . The report maintained that four dentists would be required, a reasonable conclusion given that the Commission anticipated that at least one “candy man” would also be necessary.

Both Rabbi Sacks and the Freeland League understood that what Ezekiel prophetically called the small or minor Temple (mikdash me’at) has always been sustained by the human connections that are made within its walls. And when such a synagogue is abandoned or destroyed, we mourn not only the loss of a place that had been sanctified to the worship of God but the unique web of communal relationships that thrived within it.

For many congregants, the shul has been a place of flattened social distinctions. After all, the candy man (or woman) need not be the wealthiest or most learned member of the congregation. In his new anthology, Shul Going: 2500 Years of Impressions and Reflections on Visits to the Synagogue, Charles Heller excerpts a passage from Chaim Grade’s classic novel The Yeshiva, in which “the quiet joy of praying glowed on everyone’s face—on the scholar’s and on the rich man’s by the eastern wall, as well as on the pauper’s and on the common workman’s sitting behind the pulpit.”

Heller’s selections are not all so rapturous. In his famous diary, Samuel Pepys wrote of his shock upon entering the synagogue on Creechurch Lane on October 14, 1663, which, as it happened, was Simchat Torah. “Lord,” he recounted, “to see the disorder, laughing, sporting, and no attention, but confusion in all their service, more like Brutes than people knowing the true God. . . . Away thence, with my mind strangely disturbed by them.” By contrast, the otherwise unknown Jo. Greenhalgh, had peeked into the same sanctuary just a year earlier and was “uncouthly, unaccustomedly moved”:

Tears stood in my eyes the while, to see these banished Sons of Israel standing in their ancient garb . . . solemnly and carefully looking East toward their own Country.

Synagogues: Marvels of Judaism, a sumptuous new coffee-table book, is about buildings, not communities, prayer spaces, not pray-ers. Almost every image in Synagogues is visually stunning. Unfortunately, the accompanying text about the actual communities who gave these houses of prayer their meaning does not always match this architectural beauty with critical insight.

The book’s editor, Leyla Uluhanli, writes that the synagogue expresses “the many secrets of Judaism’s phenomenal history, its creative energy, and its ability to survive,” which is true, though it might be even more true of the daily prayers recited within it. Like any anthology, the chapters vary in character and quality. Steven Fine contributes an erudite overview of synagogues in the ancient Roman world, from the now famous Dura-Europos synagogue near the Euphrates, with its colorful wall paintings of biblical scenes, to the monumental Magdala synagogue in the Golan Heights. The biblical and midrashic scenes depicted on the walls of Dura-Europos—Moses being discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter, the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, Elijah on Mount Carmel, and so on—have been preserved for posterity in the National Museum of Damascus.

Fine notes that a panel in the Hammath Tiberias synagogue, which dates from around 400 CE, includes symbols of the zodiac, including Helios the sun god riding the heavens, the third commandment’s ban on graven images notwithstanding. As many of the chapters similarly demonstrate, there have often been less-than-subtle foreign influences on synagogue designs. In Venice, the Great Spanish Synagogue’s scrolled canopy was inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s baldachin in St. Peter’s Basilica; the synagogues in nineteenth-century Krasnaya Sloboda (“Jewish Village”) in Azerbaijan were inspired by the nearby Djuma Mosque.

It is genuinely exciting to learn of the spaces in which Jews of other times and places met and prayed, danced, and kibitzed. One reads elaborate descriptions of columns, arks, windows, and wall decorations with a rush of aesthetic excitement. And then comes what feels like an increasingly inevitable postscript: “Today only a tiny population of Jews still inhabit . . .,” “Now a museum, the building was meticulously restored,” “Today, it occupies an important place in Jewish heritage tours,” “A white pebbled plaza marks the outlines of the torched former synagogue,” “Today, little remains . . . following its desecration during the World War II and its subsequent conversion into a cinema,” “Despite a horrific terrorist bombing . . .,” “The synagogue was converted into a mosque,” and so on.

The contribution on synagogues of the Middle East, North Africa, and India, coauthored by Mohammad Gharipour, an architecture professor at Morgan State University in Baltimore, and Max Fineblum, seemingly one of his students, raises this pattern to the level of egregious distortion. In their chapter’s opening line, we are told that in ancient times, early Jewish tribes inhabited the “arid ancient lands of Canaan, Phoenicia, and Palestine.” Israel and Judea, those Jewish kingdoms spanning around one thousand years or so, seem to have gotten lost somewhere in the sands of time.

Gharipour and Fineblum then describe the Central Synagogue of Aleppo. Tucked amid their rapturous descriptions of “astonishing” columns that support “a small cupola in the center of the courtyard, which was eloquently described by Pietro della Valle in 1626,” one learns:

Jews enjoyed a relatively peaceful life in Aleppo until the mid-nineteenth century, when Syrian Jews faced mounting discrimination from their Muslim neighbors. In 1947, during the formation of the State of Israel, the Central Synagogue of Aleppo was nearly eradicated.

Left unsaid in this remarkable use of the passive voice is who “nearly eradicated” the houses of worship and why. Fortunately, the synagogue “has since come under the protection of the Syrian government, and in 1992, underwent a series of renovations.” One almost expects to learn that Bashar al-Assad sponsors Kiddush along with Shabbat afternoon tours of the Duro-Europos.

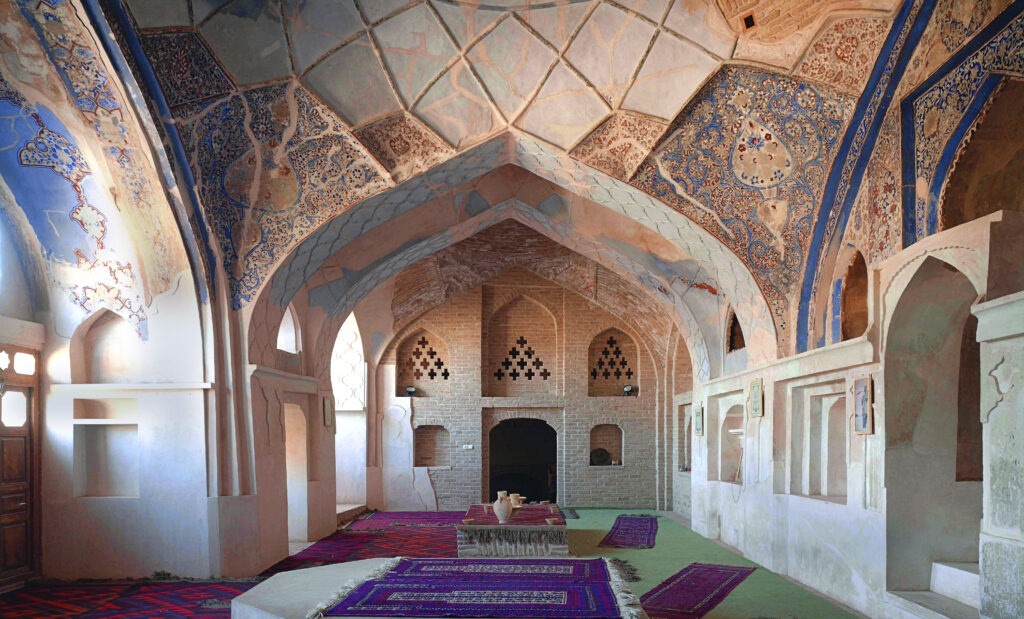

Unfortunately, there is more. In the description of Afghanistan’s Yu Aw Synagogue in Herat, in which “richly painted floral patterns inspired by Persian design . . . adorn the main sanctuary,” the authors admit that Afghanistan has not exactly been kind to the Jews, what with all of the state-sponsored pogroms and plundering. However, with antisemitism rising in the 1930s, “Herat was one of the few Afghan cities that did not banish Jews.” We then read that “the pressure to assimilate evaporated when Jews left the city in 1978.” Forced Exile = Evaporated Pressure is a nifty formula, but it misses something—human lives, or to put it more concretely, the Herat candy man and the kids who used to flock to him during mussaf.

After this, one is almost grateful that the remaining chapters about synagogues in the diaspora don’t shy from detailing the pogroms, fires, expulsions, and desecrations that have marked the history of so many of the world’s synagogues. Nonetheless, one may wish for a bit more about what went on beneath the vaulted ceilings before disaster (or diaspora) struck.

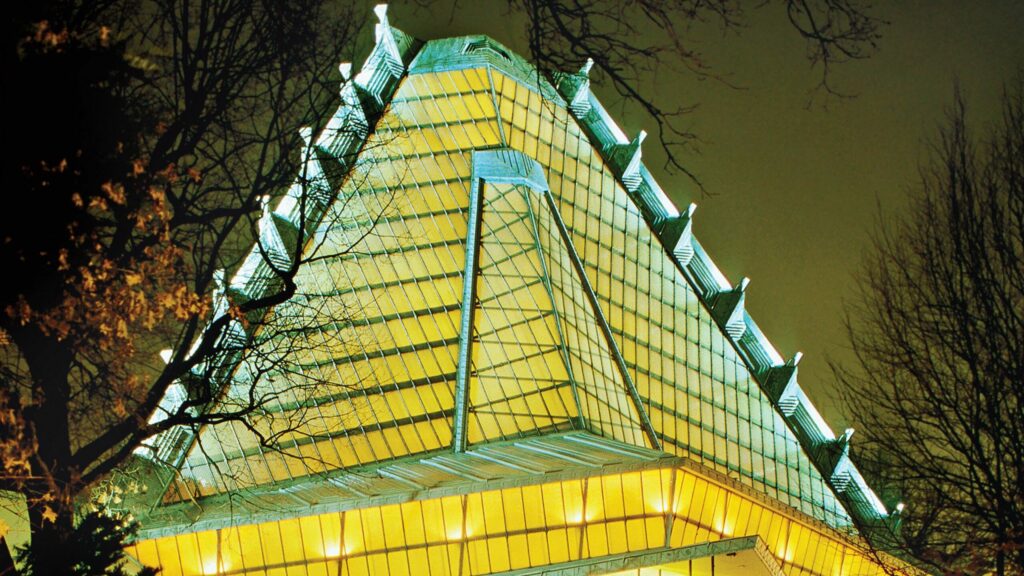

America is, of course, exceptional (bracketing lone gunman attacks, if one can even suggest such a caveat). As Samuel D. Gruber’s chapter notes, the country’s 250-year history has given Jewish Americans views from the pews to be proud of. New York’s Shearith Israel boasts windows decorated by Tiffany Studios. Frank Lloyd Wright designed Elkins Park, Pennsylvania’s Beth Sholom Congregation’s glass-paneled pyramid meant to invoke the Star of David. And Los Angeles’s Wilshire Boulevard Temple, inspired by Rome’s Pantheon, of all things, boasts murals of biblical scenes that seem straight out of Hollywood because, of course, they were. Sponsored by Warner Brothers, the renderings were painted by film director Hugo Ballin.

The word of God came to Ezekiel, and he said, translating freely but traditionally, “I have removed them far among the nations and scattered them among the lands, yet I will be to them as a little temple (mikdash me’at) in the countries where they shall come” (Ezekiel 11:16). But as Simeon Chavel recently suggested, the phrase mikdash me’at, which has come to signify the synagogues (little temples or sanctuaries) of the diaspora, might have originally just meant that after the Temple’s destruction the holy site would be accessible only to a few (me’at). Or, perhaps, he suggests more daringly, the phrase might even have meant that the Israelites would be reduced to possessing miniature models of the Jerusalem Temple as a way of recalling the actual one that once stood.

In the end, Synagogues: Marvels of Judaism reads like a collection of such models, full-color scale reproductions drained of what Émile Durkheim called the “collective effervescence” of the kids, candy men, kibitzers, and serious daveners who made these various structures not buildings but sanctuaries, holy places.

On the other hand, if you visit the ghost synagogues of Morocco, don’t miss the columns with intricate leaf patterns in the women’s gallery in Tangier.

Suggested Reading

A Tale of Two Synagogues

Frank Lloyd Wright built a dazzling temple outside Philadelphia. Too bad he didn’t look closely at the synagogue of Gwoździec, Poland, built two hundred years earlier.

Temporary Measures: Sukkah City

The reimagining of an ancient architectural ritual.

Haman, Builder of Towers, Brother of Abraham?

A new book raises the possibility that interpretive motifs from within both Jewish and Islamic traditions might have led to the uniquely Islamic tradition that Abraham and Haman were brothers.

Sephardi Lives: From Ottoman Salonica to Rosario, Argentina

Singing women spark indignation in Salonica, a change of seasons in Argentina requires rabbinic expertise, and Jews in the Ottoman army get fat and happy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In