A Little Arabic within Our Hebrew

In his new collection, Rub Salt into Love, the Israeli poet Almog Behar writes of the tumultuous movement between Hebrew and Arabic in his family history, inner world, and his life as a writer:

And now I start translating myself into Arabic

Where no one can see

Tossing and turning from one language to the other.

No longer deaf

A little less dumb

Now I know that not only in the beginning

Elohim created the heavens and the earth

But also awal ma khalaqa

Allah al-samawath we’al-ard

This stanza from the poem “The Babies in the Refugee Caravans” was originally composed in Hebrew and Arabic, with the Arabic written in Hebrew letters, presumably for the sake of readers unschooled in Arabic script, but also because this is how Arabic-speaking Jews traditionally wrote Arabic.

Behar grew up in the Israeli coastal city of Netanya, though his family hails from across a wide swath of the Jewish diaspora, including Iraq, Turkey, and Germany. Alongside Hebrew, some of his relatives are fluent in Arabic, while others speak German. The poet describes his translation between the closely related Semitic tongues as seeking harmony, or at least mutual understanding, between them and their culturally opposed speakers.

The question of Arabic’s position alongside the poet’s Hebrew is a theme that Behar has repeatedly engaged, including in his first collection, Well’s Thirst and the poem “My Arabic Is Dumb,” published some fifteen years ago:

My Arabic is dumb

Throttled from my throat

Cursing itself

Without saying a word

Asleep in the choking air of my sheltering refuge

Hiding

From my family

Behind Hebrew blinds.

In this early poem,Behar’s Arabic struggles against attempts to silence it from both external forces and from within his family unit—the origin of the poet’s own relation to the language.

The State of Israel in which Behar lives and the modern Hebrew that he speaks were, to some extent, founded on a rejection of the Diaspora and the forms of Judaism contained within it, including the Arabic-speaking Jewish cultures that flourished in Islamic lands. Arabic is also the language of Israel’s neighbors (and its Arab minority), with which it maintains strained relations. For the poet, these complications came home to roost when family members were surprised and puzzled to hear their young Sabra relative expressing a connection to their native Arabic. The Israeli melting pot forged Arabic-speaking immigrants from diverse countries like Iraq, Yemen, and Morocco into a proud Hebrew-speaking Mizrahi identity. Why turn back the clock?

Almog Behar is often thought of as a Mizrahi poet, yet his work is distinct from the most visible expression of contemporary Mizrazhi poetry, the so-called “Ars Poetica” school (an allusion not only to Horace’s classic “Art of Poetry” but also to the colloquial derogatory term for Mizrahi youth, “arsim,” which the movement sought to reclaim). Ars Poetica is an identitarian movement that calls for greater Mizrahi representation in the contemporary Israeli poetry scene. In this way, it both critiques the system while also accepting its basic contours. Behar, on the other hand, is creating new Hebrew poetry that includes, as part of its reconfiguration, Mizrahi poetry and Sephardic piyyut.

A closer, more fruitful comparison can be drawn with the celebrated Moroccan-Israeli poet Erez Biton, who has dedicated his long, distinguished career to recounting the Mizrahi-Israeli experience, present and past, writing of “trials of absorption” in Israel while longing for the kind of Jewish-Arab connections that were once commonplace. One of Biton’s most celebrated poems, “Zohra el-Fassiya,” describes the Jewish diva who once sang in the royal Moroccan court yet ended up living alone in a poor Israeli neighborhood. Her sad story can be contrasted with another of Biton’s well-known poems, the vibrant “Moroccan Wedding”:

If you never saw a Moroccan wedding —

We heard, we heard,

Your blessed hands arched over the tom-toms,

His cousin Sarah,

From one side of the village to the other

We come, both Jews and Arabs…

Along with other Mizrahi writers like Sami Shalom Chetrit, Mois Benarroch, and Vicki Shiran, Behar has been deeply inspired by Biton. The elder Moroccan poet appears in Behar’s early poetry, and is discussed in detail in his unpublished doctoral thesis (“From the Late Liturgical Jewish Poetry to the Mizrahi Literature in the 20th Century: Toward a Genealogy of Mizrahi Literature in Israel”). Now Biton shows up again in Rub Salt into Love:

And we go back to writing a little Arabic

Within our Hebrew, and we remember

Lots of ashlonak, lots of chai, we say

That’s kanunchi, that’s al-awad,

They’re all Allah-yustor, we meet and greet with Ahlan bik,

And I, I whisper “Ana min al yahud,

Ana min Baghdad,” trying to draw in some

Of Erez Biton’s cry, as he called out

“Ana min al-Magreb”. But the core is missing

From the heart, min al-kalb.

The phrase “Ana min al-yahud”—“I am one of the Jews”—is the title of one of Behar’s earlier, more impassioned works, and the line “draw in some / Of Erez Biton’s cry” recalls another earlier Behar poem, “The Thread Drawing from the Tongue.”

Despite this self-referentiality, Rub Salt into Love seems to show the poet in partial retreat from his earlier, more agitated bilingualism, modestly suggesting that “we go back to writing a little Arabic within our Hebrew.” He also finally acknowledges that the revived language of modern Hebrew is an integral part of himself. Unlike his grandmother, who returned to her native Arabic at the end of her life, Almog’s connection to Arabic will always be mediated through his native tongue:

Before she died, my grandmother went back to speaking

Only Arabic, with no Hebrew. And I,

However far away I go, will come back

In the last months of my life, before I die,

To speaking only Hebrew.

Rub Salt into Love goes beyond simply relitigating the complicated relationship between colloquial Arabic and spoken Hebrew. “The Babies in the Refugee Caravans” concludes with the opening verse of Genesis, first quoted in the original biblical Hebrew and then in the Arabic translation of the great tenth-century Iraqi sage, Rabbi Saadia Gaon.

In the writings of some of Judaism’s greatest thinkers and writers—such as Solomon ibn Gabirol, Judah Halevi, and Moses Maimonides—Behar finds a Judeo-Arabic tradition that bridges the Hebrew-Arabic divide. The Torah, in R. Saadia Gaon’s Arabic rendition, points the way to a healthier kind of relationship between the two tongues, one that restores what was lost in the silencing of Arab Jewish culture.

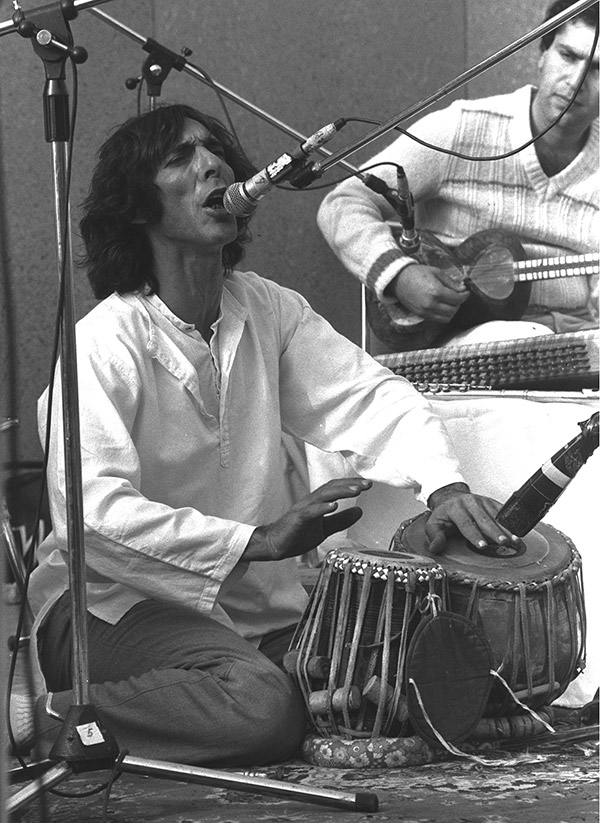

Shalom, April 1985. (Photo by Herman Chanania, National Photo Collection, Israel.)

This return to the Oriental Jewish poetic tradition would seem, at first glance, to reprise Chaim Nachman Bialik’s “discovery” of Shmuel Hanagid and Solomon ibn Gabirol’s writing and his call for Hebrew poets to return to the great Jewish poets of the Spanish Golden Age, “to set free the poetry of Spain from the cloisters of academic research and bring it into the public domain of contemporary literature.” And yet, it is instructive to recall that while Bialik understood the stature of this poetry, he also regarded the Arabic influence on it as detracting from the “purity” of the Hebrew language. Behar, on the other hand, stresses the natural flow between Hebrew and Arabic. As Maimonides put it, “As for the Arabic and Hebrew languages, everyone who knows both languages is in agreement that they are undoubtedly one and the same.”

Indeed, much distinguishes the return to medieval tradition undertaken by the modern Bialik and the postmodern Behar, as becomes clear in another poem from Rub Salt into Love:

Today is the Sabbath of the Lord; around me the streets of Jerusalem are

Crammed with synagogues like the streams of a river flowing

Down to the depths of the sea, but that stubborn pianist on the other side

Of my wall is playing like a weekday, pounding the keys, stretching

The cords of my sanity with his rehearsals. I am reading

About one of my Baghdadi ancestors who brought in the Jewish Sabbath

To the great Diwan of Abu Nuwas, and when he was asked

To sell him wine, stood by his locked door and told him:

“Today is the Sabbath, and all business is forbidden”. This Jewish refusal

Became a motif for Abu Nuwas, but I am thinking about

Forbidding business. Maybe on this day I am forbidden to busy myself

With my heart, with my fingers, with my longings

Crammed into them over the years.

Meditating on the Shabbat and its varieties was also a preoccupation of the secularizing Bialik, who sought to revive the great Jewish invention of a day of rest for the modern nation of Israel. Behar takes his Shabbat poem in another direction altogether, recalling the presence of classical Arabic literature in Jewish Sabbath observance, and the figuration of Sabbath observant Jews in classical Arabic literature, here in the writings of the Arab poet Abū Nuwās al-Salamī, who flourished under the Abbasids in the eighth century.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Behar’s poetry is the way it reflects a life devoted to reading. Unlike Biton, who had a long career as a social worker, Behar is a scholar who has the privilege of teaching and studying literature at Tel Aviv University. Rub Salt into Love includes a playful “self-interview,” with the following question-answer sequence:

“Does your writing come from wounds?”

“I write because reading has wounded me.”

Writing from personal trauma is replaced by writing that draws upon the strong emotions inspired by reading. For Behar, poetry does not emerge from distress but as a response to reading other poetry:

I collect others’ words of wisdom

And they become mine beneath my fingers as I take them down.

I don’t want to be a poet, I want

To be a historian of poetry,

Of poems.

Behar’s identity as a serious reader and accomplished scholar may explain how Rub Salt into Love ends up taking one of the more original steps in modern Hebrew poetry: namely, a sustained engagement with Muslim tradition, including the Qur’an.

One of his poems partially, evocatively, translates the ninety-fifth chapter of the Qur’an, Surah At-Tin, the chapter on “The Fig”:

I will swear by figs and olives

And Mount Sinai

That we created man in the most well-set form

And then we returned him to the lowest of the low.

Is not God the best of judges?

Elsewhere, Behar recalls how the important medieval Hebrew poet, Rabbi Moses ibn Ezra, wrote of the “Asma’ Allah Al-Husna,” or “beautiful names of God,” a liturgical sequence of ninety-nine names that plays a central role in the consciousness of religious Muslims throughout the ages:

When Rabbi Moses ibn Ezra, known as Abu Harun, quoted

From the Koran, he remembered that the Lord of the Worlds

And Master of Ladders was able to hear in it

The most beautiful names used to praise him

Since the time before creation, in the heavens and the earth.

As startling as these interreligious crossings may seem, Behar is not trying to blur the distinctions between Islam and Judaism any more than Moses ibn Ezra was. Instead, he employs Islamic tradition as a Jew rooted in his own Jewish heritage. The Qur’anic quotations and Islamic remembrances are not foreign imports into Hebrew literature. Rather, they enact an aspect of the Arab-Jewish heritage that once formed an important part of what is now known as Mizrahi culture.

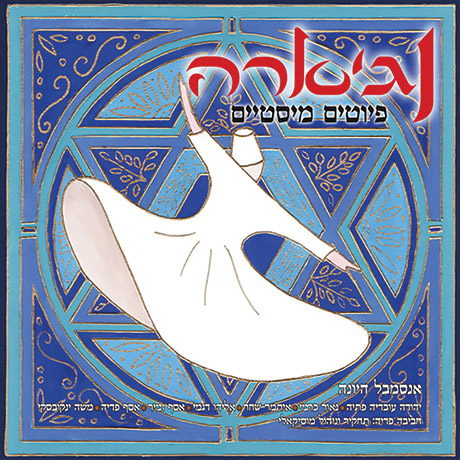

Although he is not himself a liturgical poet, Behar is fascinated and inspired by the return of piyyut, or classical liturgical poetry, to Israeli life. Poems by Ibn Gabirol and Judah Halevi have been set to music by popular Israeli singers like Berry Sakharof and Etti Ankri. The “Invitation to Piyut” website piyut.org.il, the HaYonah Ensemble (directed by the distinguished poet and scholar of Kabbalah, Haviva Pedaya), and the Singing Communities movement are changing the soundtrack of Israeli music.

Permit me to end on a somewhat personal note. In the poem “In the Bright Shining Light,” Erez Biton once called upon my late father Rabbi David Buzaglo, who was generally considered the last great traditional Sephardi liturgical poet (paytan) of the twentieth century, to step forward and take his place on the Israeli stage. As Behar recounts in the introduction to his doctoral thesis, it was in such poetic lines and moments that he rediscovered his Arab-Jewish heritage and the alternative that it offers to the trends of self-alienation that exist in modern Israeli society.

It is precisely this alternative that makes his poetry more than just the work of a gifted scholar-poet. As he writes in the poem quoted above, “I collect others’ words of wisdom / And they become mine beneath my fingers as I take them down.”

Suggested Reading

Instagramming the Holocaust

This Holocaust Memorial Day, an online project known as Eva’s Stories is uploading snippets of video every 30 minutes to the @eva.stories Instagram page.

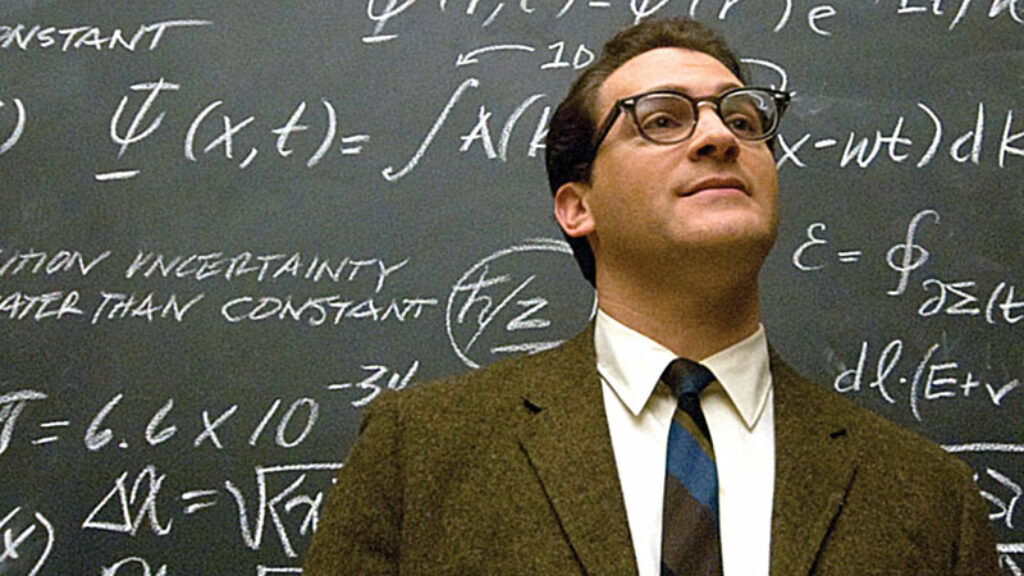

A Serious Comedy

In A Serious Man, the Coen Brothers found a way to address the realest of subjects—their own childhood, their own sense of Judaism—without sacrificing their style; they “grew up” without losing their humor.

Tragedy and Power

Barry Gewen’s new book argues that Henry Kissinger's "hardheaded Realism” was born of his family’s tragic experience in Nazi Germany.

Kissinger, Kant, and the Syrians in Lebanon

A nugget of philosophical diplomacy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In