Religious Liberty on Royce Quad

Joshua Ghayoum, a rising junior at UCLA, grew up in West Los Angeles, where his parents had settled after fleeing Iran’s radical Islamist regime. He was raised in the traditionalist Persian Jewish community, went to Hebrew school at a local synagogue, and was bar mitzvah’d there. He has traveled to Israel three times, where he visited relatives and friends. He also visits the Western Wall and other holy sites when he is there and, like many American Jews, regards the Jewish state as central to his Judaism.

demonstrates at UCLA on April 29, 2024 in Los Angeles, California. (Courtesy of Qian Weizhong/

VCG via the Associated Press.)

Ghayoum also grew up visiting UCLA. He played soccer and frisbee on Royce Quad, which sits at the center of campus, and his family even took pictures in front of the iconic Romanesque arches of Royce Hall after his brother had his bar mitzvah. As a student, he, like virtually every other undergraduate, walks through the quad almost every day to get to classes, or study at Powell, the undergraduate library across from Royce Hall—or to just hang out.

UCLA, like other elite campuses across the country, was roiled by protests against Israel after the Hamas massacre on October 7, 2023, and the ensuing Israeli invasion of Gaza. But it was not until the spring quarter that protests escalated. From April 25 to May 2, campus protests became full-blown encampments with protestors setting up tents and barriers in Royce Quad between Royce Hall and Powell Library, obstructing access to both buildings, as well as at Bruin Walk and Janss Steps, which lead to the student union complex and the western edge of the campus. Although campus antisemitism lawsuits have proliferated over the last year, the lawsuit filed against UCLA by Ghayoum and two other UCLA students differs in kind. Its centerpiece is an allegation that by actively facilitating the protesters’ encampment, the university violated the religious liberty rights of Jewish students, whose access to public spaces and buildings was restricted as a result of their religious commitments.

At the height of the encampments, Ghayoum alleges that he went to study for a midterm at Powell Library, but he was denied access by a massive pro-Palestinian barricade. Moreover, flanking the barricade were UCLA-hired private security guards. A guard, Ghayoum alleges, told him that he could not pass. When he walked to the other side of the barricade, he saw another guard who told him the same thing. Although the library was open—and accessible to protestors—Ghayoum gave up trying to enter, worried that any further attempts to gain access would likely be met with violence.

On another occasion that week, Ghayoum did attempt to pass through the encampment. According to the complaint, he was crossing Royce Quad on his way to meet a friend at Ackerman Union. When he was next to Janss Steps at the edge of the quad, he was confronted by a male protester in his twenties who told him that he couldn’t go any farther unless he was wearing a red solidarity wristband (he was, as always, wearing his Star of David necklace). To receive such a wristband, as the plaintiffs explain, one had to pledge allegiance to the anti-Israel views of the protesters and, in addition, be personally vouched for by one of them as ideologically sound. When Ghayoum ignored the man and tried to continue walking, “the protester signaled for three other male individuals of the same approximate age to join him.” As described in the declaration filed in federal court:

The four men aggressively walked toward Ghayoum, forcing him to walk backward away from the Steps. Occasionally, the activists made physical contact with Ghayoum.

Ghayoum felt as though, had he continued to walk forward, the four activists would have physically stopped him, and he felt confident that they would have also called in reinforcements.

Disavowing Israel would be a betrayal of Ghayoum’s Jewish faith.

Knowing that the situation would escalate if he continued to assert his rights, Ghayoum abandoned his effort and cancelled the meeting with his friend.

Ghayoum’s coplaintiffs, law students Yitzchok Frankel and Eden Shemuelian, describe similar experiences, as have many Jewish students at UCLA. They are represented by two prominent law firms: the nonprofit Becket Fund for Religious Liberty (with whom I have worked on occasion, though not on this case) and Clement & Murphy, a firm headed by Paul Clement, a former solicitor general to the United States. In light of the plaintiffs’ experiences on campus, their lawyers have taken to calling the encampment, which protesters sometimes called the “Free Palestine Zone,” the “Jew Exclusion Zone.” As the lawsuit goes on to note, the protesters’ requirement of a pledge of radical opposition to Israel presented the plaintiffs and other Jewish students with a choice: give up their access to campus spaces or give up their religious commitments. “Given the centrality of Jerusalem to the Jewish faith,” the lawsuit explains, “the practical effect was to deny the overwhelming majority of Jews access to the heart of the campus.”

During this chaotic week of protests, barricades, shut-down buildings, and widespread confusion, there were several confrontations. This all culminated in a violent nighttime clash between counterprotesters and protesters on the night of May 1, 2024. The next day, the University of California Police Department, which had previously been following a policy of nonconfrontation and deescalation even though the encampment violated university rules, forcibly disbanded it with the help of the California Highway Patrol, arresting more than two hundred protesters in the process. Protests, strikes, student harassment, a threatened university building takeover, and more arrests nonetheless continued throughout the spring term.

In late June, concerned that the upcoming fall quarter would bring more of the same, Frankel, Ghayoum, and Shemuelian filed for a preliminary injunction with federal judge Mark Scarsi, who is presiding over the case. Such an injunction would set ground rules for the new school year while the case is pending, ensuring Jewish students would not repeat their experiences of the previous spring. At a hearing before Judge Scarsi, UCLA resisted the imposition of such rules, arguing that the university should be given latitude to pursue policies of deescalation. UCLA acknowledged that this approach might not meet all of the plaintiffs’ demands. After all, responding to another round of encampments in the fall along these lines might require tolerating some lag time before Jews had full access to campus. But such tactics were, the university argued, in the best interests of the campus as a whole.

At the hearing, Judge Scarsi seemed unimpressed with UCLA’s push for discretion and asked the parties to come up with a workable set of rules that would “provide the Jewish students on campus some reassurance that . . . their Free Exercise [of religion] rights are not going . . . to play second fiddle to anything else.” UCLA replied with a proposed milquetoast injunction that did not, somewhat shockingly, even mention the word “Jew.”

On August 13, Judge Scarsi delivered a scathing rebuke to the university, which has broad implications for related cases across the country. In granting the plaintiffs a preliminary injunction, he pulled no punches:

In the year 2024, in the United States of America, in the State of California, in the City of Los Angeles, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. This fact is so unimaginable and so abhorrent to our constitutional guarantee of religious freedom that it bears repeating, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. UCLA does not dispute this. Instead, UCLA claims that it has no responsibility to protect the religious freedom of its Jewish students because the exclusion was engineered by third-party protesters. But under constitutional principles, UCLA may not allow services to some students when UCLA knows that other students are excluded on religious grounds, regardless of who engineered the exclusion.

The injunction unequivocally prohibited UCLA “from offering any ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas to students if [it] know[s] the ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students.”

The university at first indicated that it would appeal the injunction to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. It then, in a very public about-face, voluntarily dismissed its own appeal. Over the next several weeks, a flurry of letters, statements, policies, and initiatives were issued by the University of California system’s president, UCLA’s new interim chancellor, the director of the newly created UCLA Office of Campus Safety, and other officials, all designed to reassure students and critics that there would be no repeat of the spring quarter debacle.

The case of three UCLA Jewish students against the university may be far from its conclusion, but the first salvo from the presiding federal judge and the university’s panicked backtracking provide a view into what makes the case so unique: its simplicity. The Becket Fund (which was named after the twelfth-century Archbishop Thomas Becket, who was famously murdered in the cathedral by agents of King Henry II) is dedicated to the preservation of religious liberty, and its fundamental argument on behalf of its clients is that UCLA, by forcing students to pick between their faith and campus access, violated students’ First Amendment right to freely exercise their religion.

To appreciate the uniqueness of the UCLA lawsuit, contrast it with the avalanche of complaints and lawsuits against universities and schools for violating Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits publicly funded institutions from discriminating on the basis of race, color, or national origin. Since October 7, the Department of Education has opened more than one hundred such investigations. In addition, nearly twenty Title VI lawsuits have been filed in federal court against universities, most of them private, for failing to address pervasive campus antisemitism. Since private universities receive government funding, they, too, must abide by Title VI.

To the casual observer, Title VI might seem like a bad fit for addressing campus antisemitism. After all, Jews are generally only considered a race by antisemites, and they come in different colors and from different places. Nevertheless, for nearly two decades and across four administrations, the Department of Education has concluded that Title VI covers antisemitism as a form of discrimination on the basis of “shared ancestry and ethnic characteristics.” Moreover, courts have held that Title VI doesn’t just prohibit universities from engaging in direct discrimination; it also prohibits them from being “deliberately indifferent” to third parties within their control who engage in “severe and pervasive” discrimination.

In the words of Judge D. J. Stearns, the presiding judge in the antisemitism lawsuits filed against MIT and Harvard University, Title VI prohibits universities from “affirmatively choosing to do the wrong thing, or doing nothing, despite knowing what the law requires.” Judge Stearns threw out the lawsuit against MIT because its response to campus antisemitism, while “overly measured,” had at least a “consistent sense of purpose in returning civil order” to campus, which satisfied its legal Title VI obligations. Harvard didn’t even meet that low threshold, so he allowed the suit to go forward. These uneven outcomes are partly the result of the unique facts of each case, but they are also a consequence of the low threshold universities must meet to avoid Title VI liability. Yitzchok Frankel v. Regents of the University of California is different because although it does also allege Title VI violations, the plaintiffs’ primary claim is that, to quote Judge Scarsi, they “were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith.”

The First Amendment begins, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These constitutional religious liberty protections prohibit the government from withholding public benefits on the basis of religious criteria. But what does that have to do with student-run anti-Israel encampments and protests?

The lawsuit’s answer to the question is threefold. First, as opposed to most of the universities currently being sued for antisemitism, UCLA is a public university. That means access to its buildings, its programs, and its campus is a public benefit. Second, as alleged in the complaint, the plaintiffs’ sincerely held religious beliefs include the support of Israel. Third, the plaintiffs say that the university itself, through its agents and employees, actually facilitated the protestors’ exclusion of Jewish students from public spaces on campus because of their support of Israel. UCLA did so by deploying some of its own “Student Affairs Mitigators” and “Public Safety Aides” as well as hiring outside security teams, such as the ones Ghayoum encountered in front of Powell Library, to police the borders of the encampments and barricades erected by protesters around campus and deescalate conflicts between the protesters and other students, including counterprotesters and Jewish students like Ghayoum. As the suit alleges:

Eden Shemuelian . . . was shooed away by a security officer who chastised her and called her “the problem” for attempting to peacefully observe the encampment. And Yitzchok Frankel . . . was harassed and blocked from approaching the encampment by antisemitic activists, all with the assistance of UCLA security.

If campus officials affirmatively facilitated the protestors in setting up and policing the borders of the encampments, which was already in violation of school rules, and those encampments excluded Jews whose religious commitments included a commitment to Israel, then the university violated the First Amendment’s religious liberty protections. A university can maintain uniform, religiously neutral rules for who can and cannot enter particular campus spaces. But it can’t allow some students to set up shop in the middle of campus and then, in effect, require others to abandon their religious commitments to join them.

The fact that Jews who denounced Israel were welcomed into the encampments, as the friend of the court brief of the UCLA Faculty for Justice in Palestine pointed out, is constitutionally irrelevant. Nor does it prove that the beliefs in question were merely political and therefore not protected by the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause. The UCLA plaintiffs do not need to prove that the university or the protestors were discriminating against Jews qua Jews. They simply must prove that some students had access to the parts of campus occupied or barricaded by protesters and that they were excluded—because of their sincerely held religious commitments. As Ghayoum has said, “I consider support for Israel to be both a religious obligation and part of my ethnic cultural identity. Therefore, I cannot in good conscience forswear Israel and its right to exist.” Such a view places the plaintiffs well within the mainstream of American Jewry. Indeed, according to the most recent Pew Research Center report, eight out of ten American Jews say caring about Israel is essential or important to what being Jewish means to them.

That said, neither Judge Scarsi nor any other court who tries such a case will be asked to pass judgment on whether the plaintiffs are “theologically correct,” so to speak. Indeed, for a court to decide who is right and who is wrong about what Judaism demands would itself violate the First Amendment. In the famous words of the Supreme Court in Thomas v. Review Board, courts are not “arbiters of scriptural interpretation.” Instead, as a threshold question, a court must evaluate the sincerity of the religious commitments of these particular three plaintiffs—that is, do they believe that commitment to Israel is a religious commitment.

To be sure, not all religious liberty claims receive a court’s protection. If the government can prove a religious liberty violation is the least restrictive method to advance a compelling state interest, it can trump a plaintiff’s religious liberty claim. But UCLA’s desire to avoid conflict with protesters by tolerating the exclusion of students from public buildings and spaces is unlikely to ever pass such a test. After all, if the university would like to avoid conflict, one alternative approach that it might consider is enforcing its own rules, which prevent exclusionary encampments in the first place. In fact, this is precisely the policy UCLA has adopted in the wake of Judge Scarsi’s decision.

Only public universities like UCLA are bound by the Constitution’s First Amendment guarantee of religious liberty, but this case may also hold a lesson for private universities. In recent months, university leaders have repeatedly emphasized at congressional hearings and elsewhere that their seemingly timid responses to campus protesters who have violated university rules and norms were informed by their freely-chosen commitment to the free speech values embodied in the First Amendment. This is admirable. But, as the UCLA plaintiffs remind us, the First Amendment includes more than just a free speech clause. It also includes a free exercise clause that expresses the fundamental importance of protecting the religious liberty of all Americans.

If our universities—including our private universities—aspire to live up to the virtues and values of the First Amendment, perhaps they ought to try to live up to all of them, not least the principle of religious liberty. If they did, no student, Jewish or otherwise, would be required to disavow his or her religious commitments as the price of full-fledged inclusion in campus life.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On the Separation of Yeshiva and State

What conservative activists call religious liberty is often a deliberate blurring of the separation of church and state. Orthodox Jews ought to worry more about this, even if it might mean some vouchers for day school.

The First Amendment and the Vocabulary of Freedom

Oral arguments in a case involving two Catholic schools sometimes sounded less like a jurisprudential clash over the First Amendment than a synagogue kiddush.

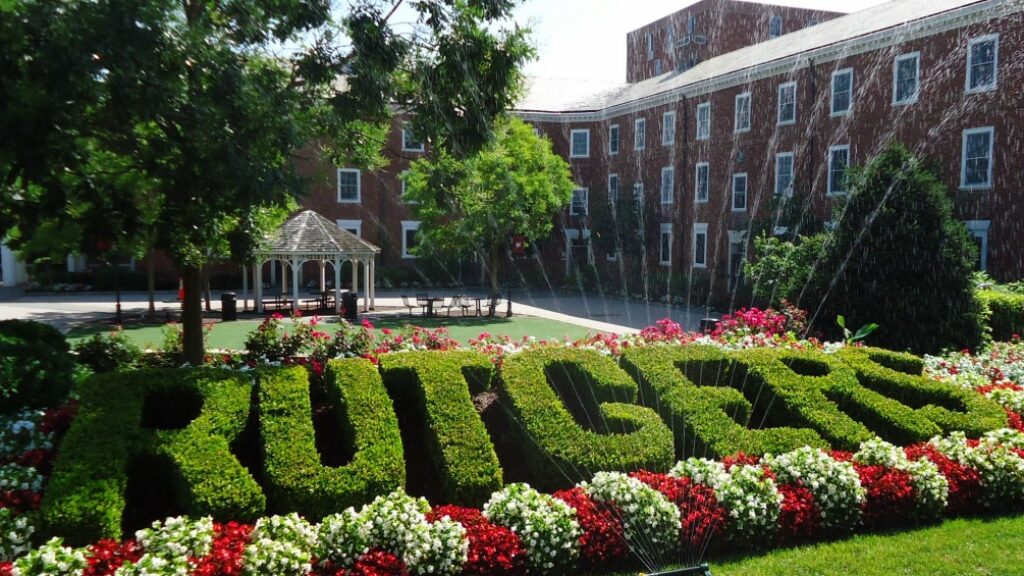

At the Anti-Israel Carnival

Students at Rutgers University protest Israel like they're attending a carnival. A professor explores the troubling scenes she's witnessed—and rereads Mikhail Bakhtin.

Welcome to the New Campus Normal: A Dispatch from Ohio State

"They found the graffiti in a stairwell. Protect Jewish Lives, only the words were crossed out by a red X." Yoshua G. B. Tolle reports on Jewish campus life amid rising antisemitism.

gershon hepner

I Simply Was Ignorant, Said Oliver Wendell Holmes

“I simply was ignorant,” was the excuse of Oliver Wendell Holmes,

explaining why he had rejected freedom

of speech before supporting it. Opinions are not chromosomes

which can’t be changed. We can and ought to weed ’em

as soon as we have got strong reasons to believe that they’re mistaken,

no less aware than was John Stuart Mill

that lots of them will be by future generations as forsaken

as beaches that have suffered an oilspill.

The comparison is mine, not JSM’s,

just like my claim that the solution

to problems depends on evolution

of errors hardly anyone condemns

until they realize that they’re

a quite mistaken way of thinking,

and cause, unfortunately, stinking

of the environment we share.

The constitutional right of freedom of our speech

forbids the interference of ideas by causing the exclusion

of any views proficient the experts do not teach,

allegedly not based on accuracy of the opiner’s conclusion.