Our Misfortune

The 1870s began auspiciously for the Jews of Germany, when the unification of the German Empire culminated in the adoption of a constitution that finally granted them fully equal rights. The decade ended less happily, however, with the emergence of an antisemitic movement that posed a threat to all of the progress they had made in the previous century.

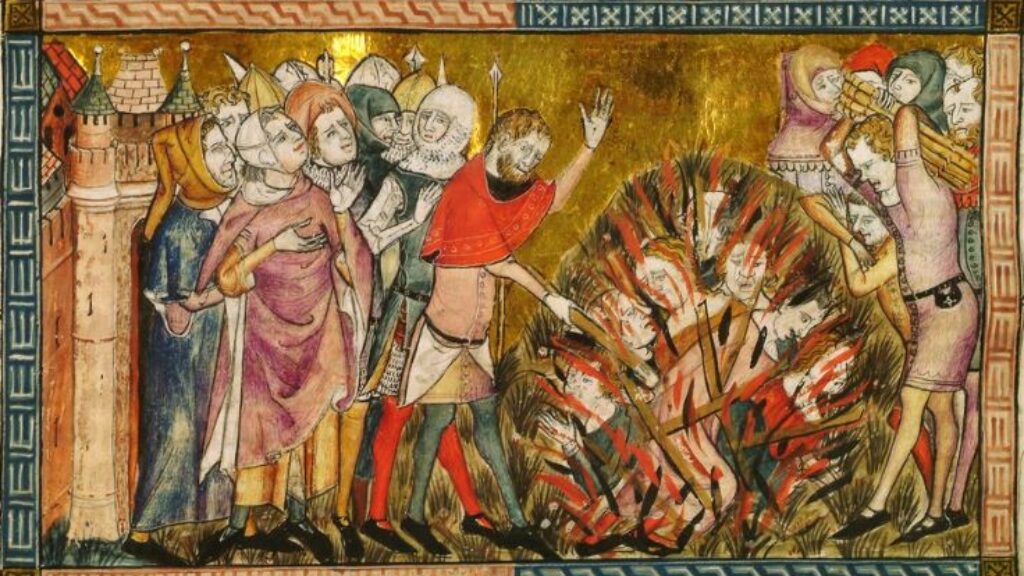

Like the great Israeli social historian Jacob Katz and others who have studied the rise of antisemitism in Germany, Frederick C. Beiser stresses the pivotal importance of the economic depression that hit the country in 1873 and the extent to which a few journalists writing in a few influential periodicals pinned responsibility for it on various prominent Jews. These Jews supposedly had a stranglehold on the German economy and culture amounting to a virtual takeover of the country. In March 1879, a fairly obscure journalist named Wilhelm Marr published a pamphlet titled The Victory of Judaism over Germandom, which garnered a lot of attention and paved the way toward his founding later that year of an organization called the League of Antisemites (Marr invented the term). The other man most responsible for stirring things up was Adolf Stöcker, the official preacher to the Prussian Imperial Court, whose newly formed Social-Christian Workers’ Party marked the beginning, in Beiser’s words, “of the political organization of the antisemitic movement in Germany.”

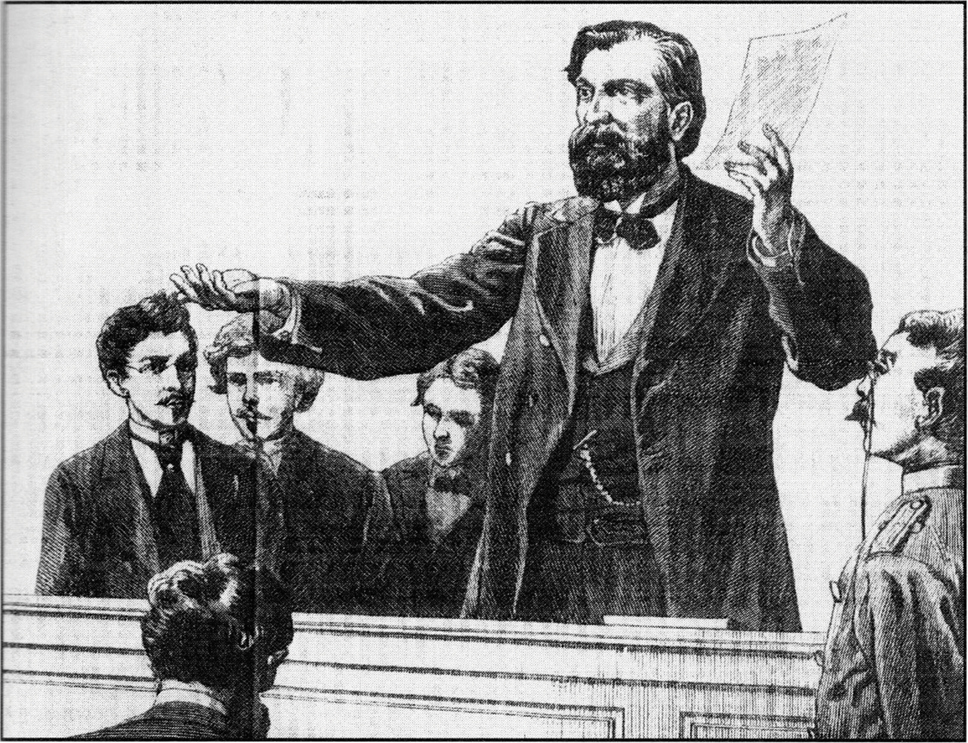

Stöcker himself was no original thinker, nor was he, strictly speaking, an antisemite, if one understands that term to denote, as it did for Marr, hostility toward Jews on racial grounds. Stöcker, in fact, strenuously insisted on the redeemability of Jews—if they converted. But he was a man who knew how to take advantage of an opening. His original incentive for entering politics had been to win back the workers from the left and return them to the church and the flag with a program for social and economic reform. Only when he began to pound on the danger posed by the Jews, however, in September 1879, did he get a real audience, though it consisted of members of the lower middle class, not workers. “It was Stöcker who made antisemitism into a political cause and a popular force,” Beiser writes.

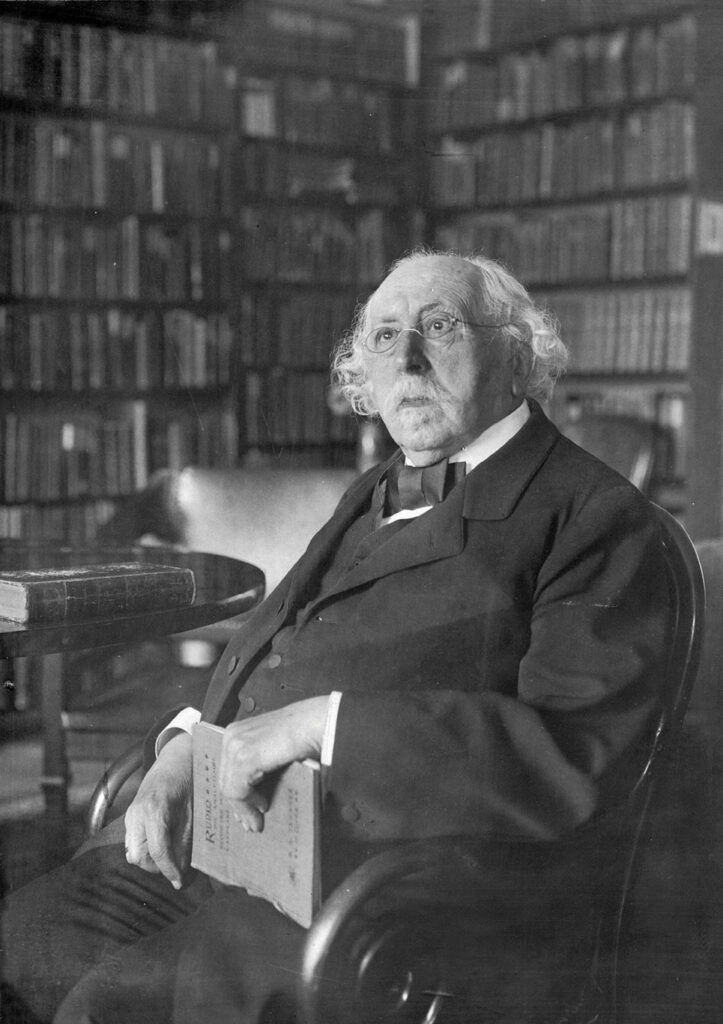

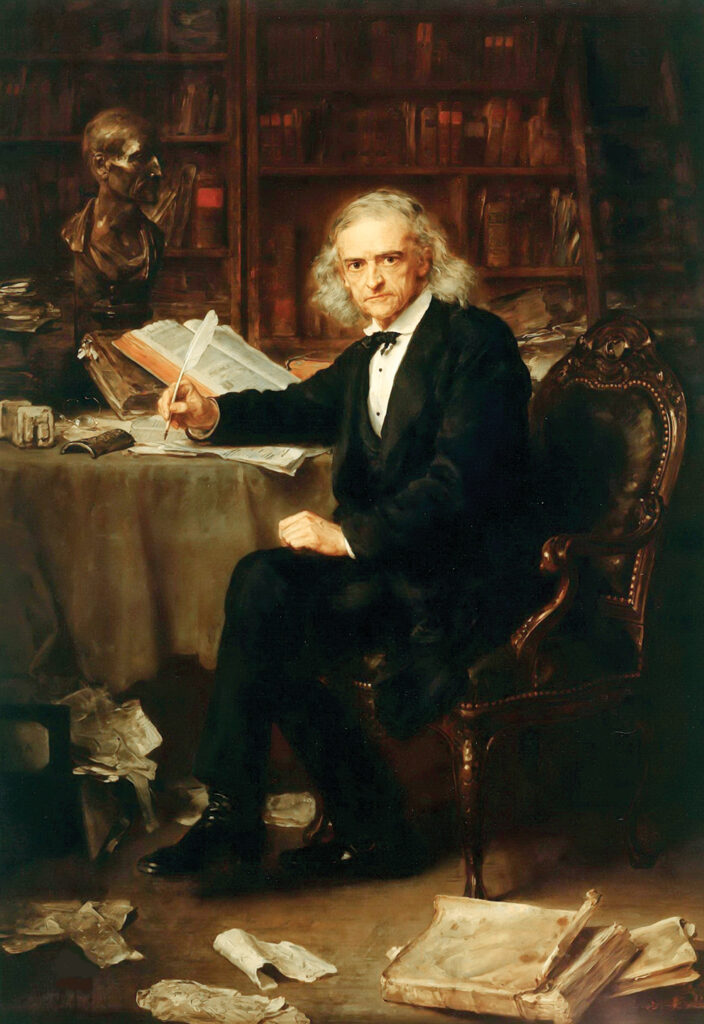

In his important new book on what came to be known as “the Berlin antisemitism controversy,” Beiser focuses on a far more rarefied version of this discourse. The key figure was Heinrich von Treitschke, who was a leading nationalist historian, editor of the important Historische Zeitschrift, and a prominent legislator. He was widely known as “the herald of the Reich,” of a unified Germany, and he had had nothing to do with the antisemitic movement during the years that it began to take shape. But in November 1879, he published an article surveying current events that concluded with a few pages on the recent rise of antisemitism.

Treitschke deplored the “dirt and brutality” in antisemitic activities. But he quickly acknowledged that the stir they were creating showed that “the instinct of the masses has in fact correctly recognized a grave danger, a very considerable fault of the new German life.” In part, he complained, the threat stemmed from immigration:

The Eastern border of our country is invaded year after year by multitudes of assiduous trouser-selling youths from the inexhaustible cradle of Poland, whose children and grandchildren are to be the future rulers of Germany’s stock exchanges and Germany’s press; this immigration is rapidly increasing and the question becomes more and more serious how this alien nationality can be amalgamated with ours.

It wouldn’t have been so bad, Treitschke said, if these newcomers belonged, like the ancestors of French and English Jews, to the more easily assimilable Spanish branch of the Jewish people, but they came from “the Polish branch, which bears the deep scars of centuries of Christian tyranny . . . they are incomparably more alien to the European, and especially to the Germanic character.”

Treitschke didn’t call, however, for better policing of the border, or even for discriminatory legislation to prevent assimilated Jews from assuming positions of authority. He spoke more generally and vaguely:

What we have to demand from our Jewish fellow-citizens is simple: that they become Germans, feel themselves simply and justly as Germans—regardless of their faith and their old sacred memories which all of us hold in reverence; for we do not want thousands of years of Germanic civilization to be followed by an era of German-Jewish mixed culture.

There were, Treitschke readily acknowledged, plenty of examples of individuals, like Felix Mendelssohn, the great (and converted) composer, and Gabriel Riesser, the loyal Jew and German patriot who had been vice president of the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848, who acted and lived as members of the German nation. Regrettably, however, there were also “numerous and powerful circles among our Jewry who clearly do not intend simply to become Germans.”

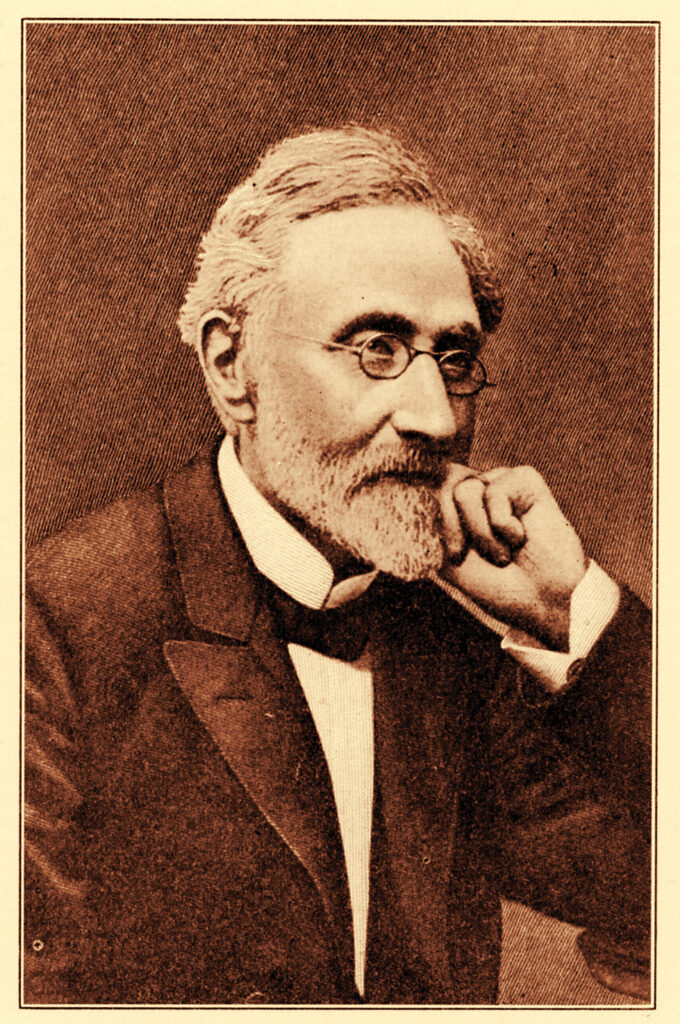

The worst example of such stiff-neckedness was the Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz, whose voluminous History of the Jews was replete, Treitschke complained, with insulting descriptions of the greatest figures in German history. But “this stubborn contempt for the German goyim is not at all merely the attitude of an isolated fanatic.” It also characterized plenty of corrupt business people who “share heavily in the guilt for the contemptible materialism of our age.” The Jews were underrepresented among the leading figures in the arts and sciences and overrepresented in the press, where they mocked Christianity. In short, there was good reason to proclaim, as so many did, that “the Jews are our misfortune.”

The solution, according to Treitschke, was definitely not to abolish or limit Jewish rights but for the Jews themselves to take the initiative and “make up their minds without reservations to be Germans, as many of them have done already long ago, to their advantage and ours.” This transformation, he resignedly noted, would never completely eliminate the problem, but it would help.

“It is not what Treitschke said during the antisemitism controversy” that was so important, Beiser tells us, but “who Treitschke was that made all the difference.” A professor of history at the University of Berlin and a leader of the National Liberal Party, he had established himself in the 1860s as “the most eloquent and powerful voice for German unification.” But he was also a man with many Jewish friends, so it came as a shock when he more or less sided with the antisemites. Old friends and new enemies, prominent academics, rabbis, and political leaders all wanted to have their say. Almost all of the participants in this controversy were Jewish, at least by birth, and almost all were critical. Treitschke responded to several of them, rarely yielding an inch.

“How indeed,” complained an Orthodox rabbi named Seligmann Meyer, “could the German Jews be more German than they are already? They speak German, they act like Germans, they dress like Germans, and they regard themselves as Germans.” Moritz Lazarus, an important philosopher, social psychologist, and communal activist, responded to Treitschke with what Beiser calls “a classic statement of the liberal Jewish position about nationality”: “The Jews are no longer a nation but a religious group,” Lazarus wrote, “and religion and nationality should be entirely separate matters.” He believed, as Beiser puts it, that “as long as Jews spoke German, and as long as they identified as German, they really were Germans.” Harry Bresslau, an academic historian and a personal friend of Treitschke’s, admitted that there were still a few Jews in Germany who considered Palestine to be the promised land, but he insisted that there weren’t many of them. Heinrich Oppenheim, a Jewish veteran of the National Liberal Party, likewise highlighted the patriotism of German Jews while acknowledging that there were “some fanatical and perverse scholars among the Jews,” like Graetz, who rejected assimilation. But the Jews in general, he insisted, were “no more responsible for Herr Graetz than Treitschke is for the Kingdom of Saxony” (which had been absorbed into the new Reich in 1871).

Graetz himself was one of the first to respond to Treitschke, but he was more interested in demonstrating Treitschke’s historical errors than in affirming the patriotism of German Jews. Treitschke hit back hard. Graetz’s plan for the future, he wrote, was encapsulated in a sentence in his History of the Jews acknowledging that in the years since 1848, “recognition of the Jews’ equal rights had taken place but the recognition of Judaism had not.” What did Graetz mean by this, asked Treitschke, other than “the recognition of Judaism as a nation in and alongside the German?” But if that was what he wanted, he should try to found a Jewish state somewhere else and see whether anyone would recognize it. “On German soil,” however, “there is no room for double-nationality.”

Graetz protested, convincingly enough, that Treitschke was misreading him and that what he had intended to say was that Judaism, as a religion, had not been placed by the government on the same plane as Christianity. “Is Judaism identical with nationality?” he asked. He left the question hanging, as if it were too absurd to deserve a response. But as Ismar Schorsch has shown (and Beiser doesn’t make sufficiently clear), Graetz was in fact “steeped in Jewish national sentiment” and “never ceased to regard Judaism as anything but a national religion.”

None of this made Graetz popular among the other Jewish participants in the antisemitism controversy. National Liberal Party leader Ludwig Bamberger called him “a Stöcker of the Synagogue”; philosopher Hermann Cohen, who had himself been a student of Graetz, “reassured Treitschke that Graetz was no spokesman for Jewish opinion, and that there was no circle in which he had any influence”; and Ludwig Philippson, the editor of the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, “declared Graetz’s views unrepresentative of German Jewry.”

But Treitschke was not placated by such reassurances. Instead of praising his Jewish critics’ readiness to carry on the venerable tradition of Gabriel Riesser, as one might have expected, he raised the bar. Although in his original article he had only noted, in passing, that the Germans were a Christian nation, he now stressed the degree to which Germanness and Christianity were inextricably bound up with one another. He expressed this position most clearly in his response to Moritz Lazarus, which Beiser trenchantly summarizes:

Treitschke explained that though he was no proponent of the doctrine of a Christian state, he still held that Germany was a Christian nation. Every step forward he took in his knowledge of German history convinced him, he revealed, “how closely Christianity has grown with all the fibres of our national being.” German science and art are Christian; German institutions and traditions are Christian; German morals and mores are Christian. Judaism, however, is the national religion of “a tribe completely foreign to us” (eines uns ursprünglich fremden Stammes), and a tribe that is very exclusive and self‑enclosed. It is a mistake of Lazarus to assume, therefore, that Judaism is as German as Christianity.

Treitschke didn’t actually come out and say that one therefore had to become a Christian to become a real German, but it is hard to see how he believed such a self-transformation might otherwise be possible.

While the highbrows were exchanging blows in their journals, the antisemitic agitators were busy trying to change the facts on the ground. From the spring of 1880 onward, they circulated a petition calling for forceful measures against the Jews, including the prevention or at least the curtailment of Jewish immigration into Germany, the exclusion of Jews from all positions of authority, and the elimination of Jews from the rosters of primary school teachers. In April 1881, they submitted their petition, with a quarter-million signatures, to Chancellor Bismarck, who ignored it.

Treitschke did much the same—publicly. As a liberal, and as a man who had stated his opposition to any rollback of Jewish emancipation, he couldn’t very well voice his approval of the petition. But privately, he seems to have given it his blessing. In October 1880, an antisemitic young law student named Paul Dulon came to visit him to discuss the issue. “Dulon left the meeting elated. He had gained his prize: Treitschke’s encouragement.” He reported the great man as saying that “I see not only no reason for discouraging you, but also I wish you much luck in doing so.”

Dulon revealed Treitschke’s position in a public letter that made its way into the hands of fellow historian Theodor Mommsen, who confronted Treitschke about it. Treitschke backpedaled, at least in part, because anything that smacked of political activism could get him in trouble at his university. He claimed that:

When he read the letter in a newspaper he was astounded. Never, he implied, did he wish the student luck in his efforts to collect signatures. Angry and indignant, Treitschke immediately wrote the student and demanded that the passage citing him be deleted.

Mommsen, it seems, was satisfied. Beiser, with good reason, isn’t. “Was Treitschke lying?” he asks, and then provides sufficient evidence to lead one to conclude that it is “probable that Treitschke was playing with the facts to save his dignity.”

“The foremost spokesman for German nationalism,” writes Beiser, “had thus become, willy-nilly, the foremost spokesmen for antisemitism”—if not, perhaps, the boldest one. How could a lifelong liberal veer so far in such an illiberal direction?

Beiser stresses the depth and the durability of Treitschke’s nineteenth-century European liberalism but also the limitations to it. Deep-seated as were his commitments to “constitutional government, personal liberty, and freedom of conscience and inquiry,” these principles were always in some tension with Treitschke’s nationalism, even as he maintained that “there was ultimately no contradiction between” them. Nonetheless, he thought, there were times when liberalism had to give way to nationalism.

Treitschke was not exactly a romantic nationalist, but his “conception of the new German nation is very much based on the idea of the Volksgeist, of the people sharing a common heritage and having a common history.” Nevertheless, he for a long time cast no doubt on the ability of German Jews to partake in this commonality. In the 1870s, however, after the defeat of the enemies of German unification, Treitschke, according to Beiser, “had to focus on new enemies,” which were “all the centrifugal forces within the new Reich.” These included the religious differences between Protestants and Catholics, and, “more ominously, there was the new materialist and egoist mentality of the 1870s, according to which every person should seek his self-interest and economic gain.”

In view of these concerns, it was inevitable, Beiser writes, that Treitschke would ultimately reconsider his stance toward the Jews. At the end of the 1870s, after the relaxation of tensions between Protestants and Catholics:

They were indeed the most powerful centrifugal force in the new Reich. To be sure, they were a small minority; but they had an influence far beyond their numbers. They were not only a distinct ethnic group, a nation within the nation, because they did not share its language, culture or religion; but they were also the business and financial leaders, the chief representatives of the new commercial spirit of the nation.

There was also the fact that the left-wing liberals with whom Treitschke broke in the 1870s were led by Eduard Lasker and other people who seemed to constitute “a Jewish cabal in the Reichtstag conspiring against the monarchy and military.” Last, there was Treitschke’s growing appreciation of the role of Christianity as a unifying cultural force in the state and “the best antidote to the materialism and egoism of the age.” Judaism he perceived, on the contrary, as a moribund religion that had degenerated into a secularizing force typified by subversive figures like “Ludwig Börne, Heinrich Heine and their countless epigoni in the German press, who loved to ridicule Christianity.” The Jews had to be dealt with—not by being defeated or deprived of their rights but by being cajoled into abandoning their separate identity and assimilating into the German people.

Beiser sizes up Treitschke’s outlook objectively, not sympathetically, but it is still startling to see how he takes for granted the basic accuracy of the German historian’s depiction of all too many of his Jewish fellow citizens in 1879 as members of a culturally alien nation within a nation. He does so, at least in part, on the basis of a misreading of Jacob Katz. At the very beginning of his book, he endorses what he takes to be Katz’s description of the German Jews of this period in his Out of the Ghetto as “an alien subgroup within Germany, having their own culture, religion, languages (Hebrew and Yiddish), and ethnic identity.” Katz thus acknowledges, according to Beiser, that by refusing to assimilate, “the Jews showed that they were indeed a state within the state, a nation within the nation, which raised troubling questions about their loyalty and allegiance to the new national German state, which was founded only in 1871.”

In the passages to which Beiser refers, Katz does indeed highlight the degree to which German Jews at this time continued to retain some of the attributes of a distinctive subgroup, including their concentration in certain spheres of the economy and comparative social isolation. But he also stressed, in the book to which Beiser refers, both that they had by the 1870s largely lost their Hebrew and Yiddish and that their longstanding “cultural isolation was almost completely gone.” Katz observes that they had not really transformed their identity, as many of their leaders wished, into that of a group defined solely by its religion, but he doesn’t come at all close to acknowledging, as Beiser would have it, that their enduring ethnic characteristics and affiliations showed that they retained a separate national identity and constituted “a state within a state.” Beyond that, quite apart from what Katz says or doesn’t say, nothing shows more clearly how remote Germany’s Jews were from a Jewish nationalist self-conception than their passionate and patriotic reactions to Treitschke.

Something other than the German Jews’ troubling survival as a separate nation, therefore, must have triggered Treitschke’s antisemitic outbursts. And whatever that may have been, it had unquestionably real historical consequences. The Berlin antisemitism controversy, it is true, wound down after a little more than a year. To some extent, it did so in a way that left room for hope. A November 1880 “Declaration of the Notables,” signed by seventy-five high-ranking academics and other cultural, religious, and social leaders, was a rebuke to antisemitism (and, implicitly, it seemed, to Treitschke). But the antisemitic movement did not stop. And the fact that a historian of Treitschke’s stature, a man who played such a large role in the formation of modern German national identity, had sided with the antisemites was a real asset to it, both in the short run, while he was alive, and in the following decades.

For one thing, the phrase that he popularized, “The Jews are our misfortune,” became part of everyday parlance in Germany. When Julius Streicher launched the infamous Nazi tabloid Der Stürmer in 1923, he used the phrase as its logo. It appeared in bold letters at the foot of the front page of every issue until it ceased publication at the end of World War II.

Suggested Reading

Jews, Genes, and the Black Death

This is the version of history that many of us heard in Hebrew school: Jews were saved from the plague by handwashing, kashrut, and burying their dead quickly.

Revolution, the Jews, and Hitler’s Munich

How did a Jewish Socialist become the revolutionary leader of the People’s State of Bavaria? And did his brief career provoke the rise of Hitler?

What’s Going On With Antisemitism?

Jonathan Karp responds to Reviel Netz

The Bible Scholar Who Didn’t Know Hebrew

The surprising story of Elias Bickerman and his scholarship.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In