Camp Mountain Lake, 1977

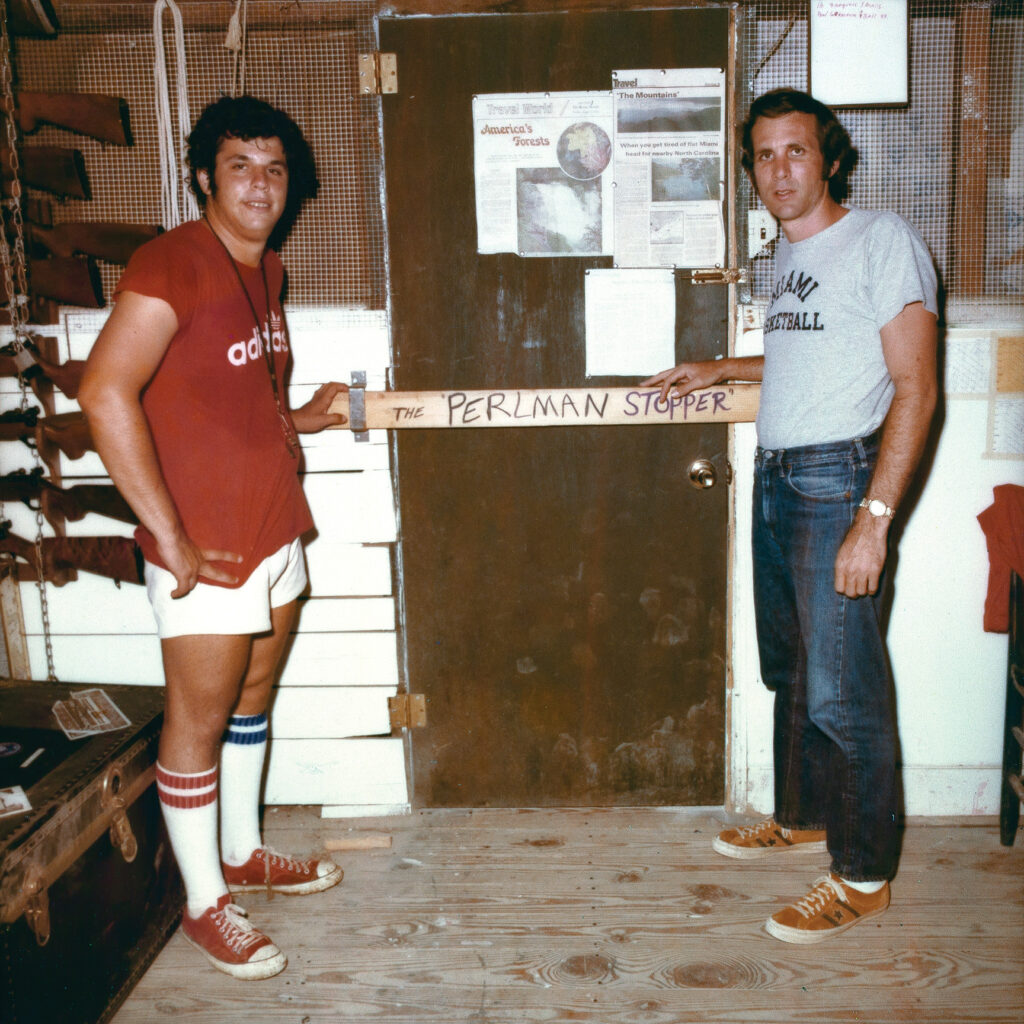

Two camp counselors bracket the doorway. On the left, the younger of the two is sunburned and sweating. The locks of his curly brown hair stick up like digressions from the tangled whole. His bright red Adidas T-shirt sticks to his chest; his low-top Converse sneakers, the same color as his shirt, are scuffed and muddy. He’s wearing tiny white athletic shorts and just-below-the-knee tube socks, one ringed around the top in red, the other in blue. He stands in front of a wall of rifles, only their butts visible in the frame, all chained up for safety.

The man on the right is older, with a longer face and a smaller mouth. His hair is well kempt, but he hasn’t skimped on the sideburns, either. He wears a grey “Miami Basketball” T-shirt tucked into dark blue jeans, a simple silver watch on his dangling arm, and a pair of ochre Converse.

Between the two of them is THE PERLMAN STOPPER, a plank of wood holding the door closed for a pretty clearly stated purpose (whoever Perlman was). Each of the men smiles faintly at the camera. They are tired. It’s the summer of 1977 at Camp Mountain Lake in Hendersonville, North Carolina, a de facto Jewish camp largely composed of Jews from Miami.

A former camper and counselor named Andy Sweet is taking their picture. He’s 24 years old, and in 1982, he’ll be brutally murdered in his Miami condo. The subsequent investigations and trials will leave questions about which of the three men charged were responsible.

As the son of a prominent Miami family—Sweet’s father was a judge, his mother a socialite who came from Miami hotel money—and a brilliant street photographer who was out with his camera every day, Sweet was already known on Miami’s social scene. An article in the Miami Herald: written shortly after his death described how summer camp helped make him a photographer.

The picture-taking began when he was still a little kid, at Camp Mountain Lake in North Carolina. The owners of the camp remember a chubby kid, not very athletic, and the camera was a way of making friends. At first, the letters home were typical, scrawled in slapdash handwriting, more inventive in their grammar than in content: “Dear Mom and Dad. I took horseback riding and art and crafts. In an hour I will go to eathar riding art. I went sming today. Love Andy.”

Then a suspicious outburst of meticulous spelling and the painstakingly lucid handwriting usually associated with a major request: “My tank spool in my darkroom broke. Go to the photo mart and please get an anscomatic developing tank spool for 35mm or bigger. Not the tank. Just the spool. It should not cost over $3. I am editor of the camp newspaper. Please write. I haven’t gotten a letter in three days.”

The photos that Sweet took the summer he revisited Camp Mountain Lake were later used for his MFA thesis at the University of Colorado at Boulder. They’ve been collected and published for the first time in Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah: Andy Sweet’s Summer Camp 1977, part of a continuing series from Letter16 Press that began last year with Shtetl in the Sun: Andy Sweet’s South Beach 1977–1980.

The existence of enough of Sweet’s art to make even a single book is extraordinary. After his death, his family had deposited his negatives and some prints in a high-end art archive that lost them in a move. His large-format prints, stored under his mother’s bed, gradually lost their color as the years passed. Then, in 2006, a few hundred smaller-format work prints were found in a family storage space. His sister’s husband, a graphic designer, was able to restore them, bringing back their vibrant colors.

Between 1977 and 1982, Sweet had worked with his close friend and fellow photographer Gary Monroe on what they called the Miami Beach Photographic Project, with support from the National Endowment for the Arts. Miami was changing; the days of South Beach as a glamorous Rat Pack playground were long gone, to say nothing of the glittering 40s and 50s. In just a few years, the Mariel Boat Lift, bringing 125,000 Cuban refugees to the city, would change Miami even further. Sweet and Monroe set out to capture the city in transition, not quite what it was, but not yet what it would become, either. On New Year’s Eve, they’d drop in on the old-timers’ soirees and party right along with them, snapping photos all the while.

Monroe, mordant, workman-like, and serious about photography, shot the city in black and white, often waking at dawn. Sweet, by all accounts a gregarious, tender man, shot in the afternoon, in rich, vibrant color. His most frequent subjects were the aging Holocaust survivors and northeastern transplants of Miami’s Jewish community.

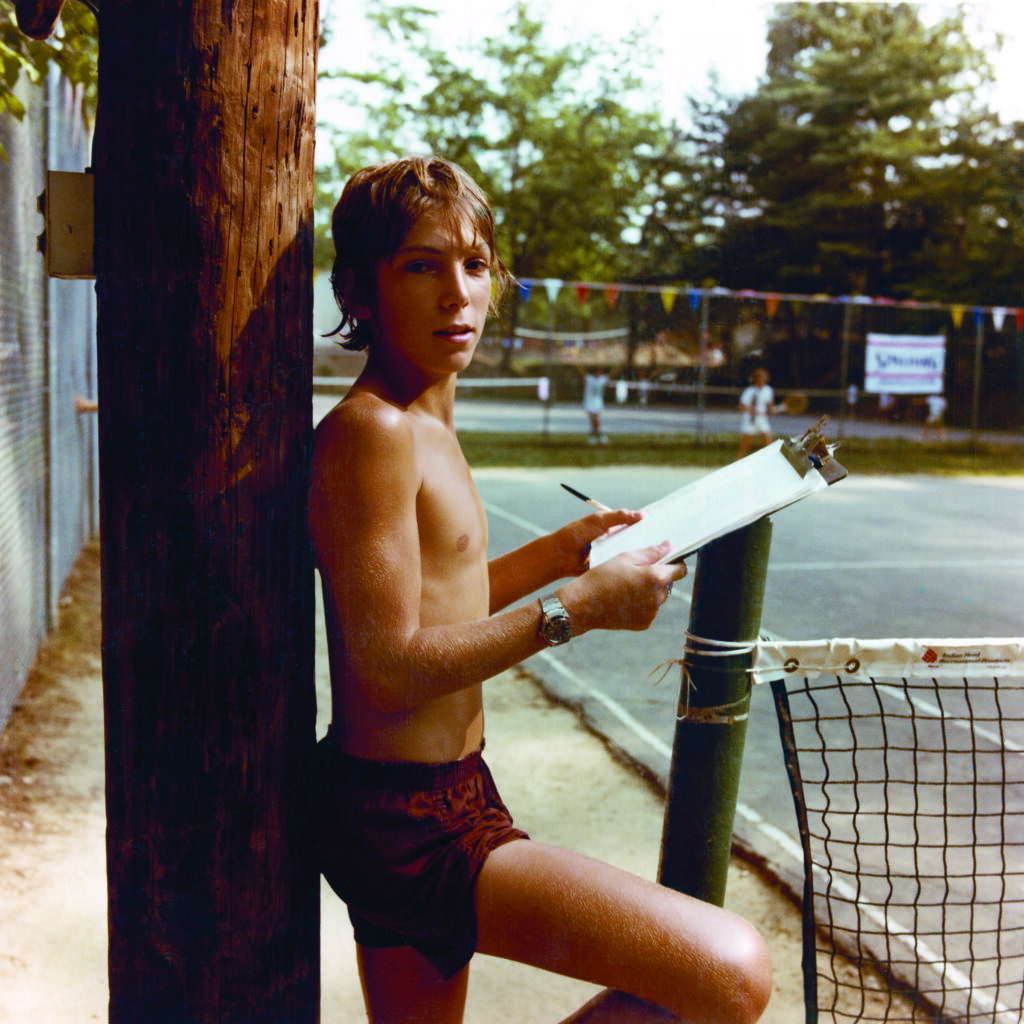

Sweet didn’t just shoot in color; he shot in the idiom of people’s actual lives. In the art world of the late 1970s, color photography was still considered gaudy, mass-market eye-candy that was better suited for advertising or family portraits than for an exhibition. But look at his shots of the color war at Camp Mountain Lake, or of paunchy, tanning yentas stuffed into swimsuits in hues most commonly found among rare Amazonian birds, and you see the fault in such thinking. The color is part of the story.

“I want my photos to be truthful accounts,” Sweet once wrote. “The color is a device to include more reality.” What more truthful account can there be of life at a Jewish summer camp in 1977 than two long-haired Jewish adolescents wearing T-shirts with images of the Fonz and Elvis Presley? The King died at the end of that summer, and I found myself wondering whether the boy felt like wearing the shirt afterward.

Sweet’s subjects are typically in the dead center of the frame, often smiling at the camera, like a snapshot for the family album. His photos aren’t formal, but they’re not candid, either. He usually gives his subjects the chance to pose in a way that reflects how they understand themselves: goofy, serious, sexy, gloomy, and everything in between.

In Shtetl in the Sun, Sweet portrayed South Beach alte kakers with fresh memories of Nazi Europe; in Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah, their grandchildren giddily arrive at Camp Mountain Lake, smiling through a flurry of luggage, lines, and uniforms. In the introduction to Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah, Naomi Fry considers what’s shared between the campers and the subjects of Shtetl in the Sun. If the latter is “an elegy for a dying tribe,” then the former features campers who “veritably burst with cocky new life.”

Campers tallied up bug bites and worked on summer tans, wearing clothes that would make them indistinguishable from their Gentile peers. Back in Miami, attendees of prayer services and Yiddish cultural events are dressed in wild floral prints and Havana hats.

Consider how much had to be built and destroyed and built again for Sweet to produce the images he produced. Example: a smiling young blonde girl, probably the grandchild of survivors, cradling a rifle longer than her body at a Jewish summer camp near Hendersonville, North Carolina, a city with a main street built by slave labor.

Summer camp in the 1970s was not some lost Eden, though it’s hard not to think so while looking at these pictures during this summer of COVID. Rather, Sweet’s photos capture American Jewish life in motion. At Camp Mountain Lake, and back in Miami, Jews were forming a new, distinctly American way of Jewish life. For better or worse, Sweet’s subjects straddle the line between total assimilation and stubbornly insisting on their difference.

In the foreword to Miami Beach, a 1991 collection from Sweet and Monroe’s Miami Beach project, Isaac Bashevis Singer recommended the book to “all art lovers and those who are especially interested in ethnic culture in this land of freedom.”

The United States of America is not a laboratory of total assimilation. The very opposite. It grants freedom to people to grow in their own culture, in their own way of life altered to their roots, their languages, to their hopes and wishes…The immigrants who came here from all over the world did not come to forget their history, their origin, and their ethnic identities.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Homage to Mahj

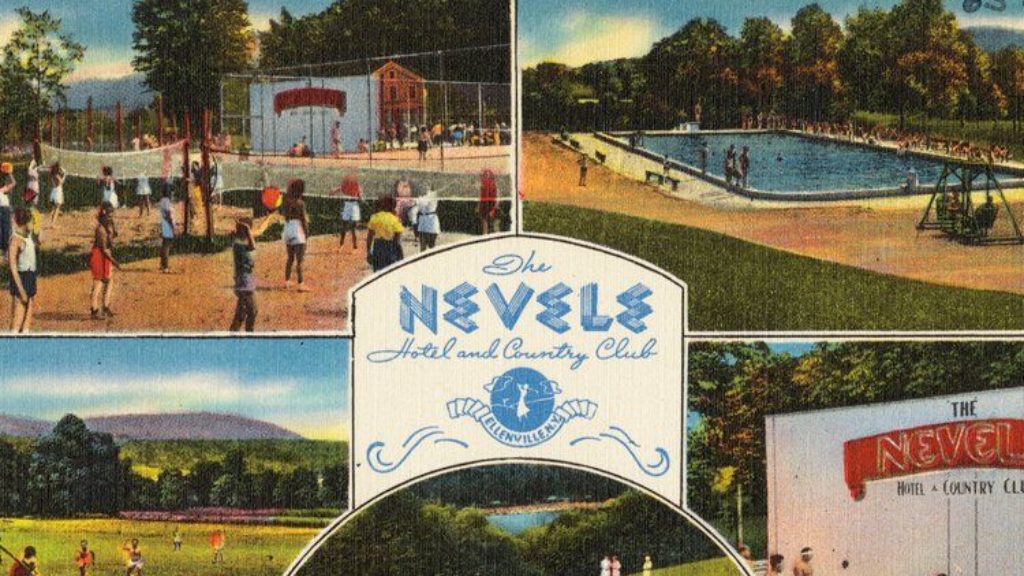

A traveling exhibit attempts to explain the Jewish fascination with Mah Jongg, a favorite past-time of mid-century Jewish suburbia, Jewish country clubs, and Catskill resorts.

Summer of ’36

By 1936, Joseph Roth’s alcoholism was increasingly desperate, and his friendship with Stefan Zweig was frayed. But still that summer gave them an opportunity to recover something of their old friendship.

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

The Home Front

Eating very long breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with dozens of aging members of the Greatest Generation was the best part of Arkush's teaching experience.

david gerber

I haven't looked at either of Sweet's books, but I can tell you from my own childhood experience that the color wars I lived through at overnight camp in Wisconsin were no joke, nor are they especially fondly remembered. I guess they are burned in my brain as memories over 60 years later, because I saw some of the worst adult behavior, prompted by excessive competitive zeal, imaginable. I've told myself for many years, it was time to write out those memories, and maybe I will. They speak to the male world of assimilating Jews, and the anxieties that fathers had for their sons' ability to enter the competitive jungle of postwar American capitalism that was still perceived as hostile to Jews. Overnight camp was supposed to condition those male children to be tough and prepared for the moral equivalent of war. The color war instead succeeded in scaring in the hell out of many of them.

philip

In the late 60s and the early 80s, I visited another camp in Hendersonville: Camp Blue Star. Also a Jewish camp, with kids from all over the South. It was the venue for Fred Berk's annual Folk dance workshops at a critical time, when Fred was spreading Israeli and Jewish folk dancing throughout the Jewish and Zionist youth movements of America primarily by training the teachers.

I heard stories of trouble the camp had in its early years with local residents because the owners gave their mostly-Black help all Sunday and half of Saturday off from work. Too generous, they were told.

One experience remains with me. A nice liberal Jewish 18-year-old boy from New York, I drove down to Hendersonville in a VW bug with my bearded and be-sandaled Israeli friend, a white Jewish girl from Westchester, and a black Jewish girl from the Bronx. It was Freedom Summer. When we crossed into NC we stopped for gas. I thought we were getting some funny looks. I went into the gas station office and found a tall stack of flyers for the week's KKK meeting on the desk. We left quickly and high-tailed it for Hendersonville. We encountered no trouble, despite our active imagination. Serves us right for imagining the worst.