Summer of ’36

The Belgian resort town of Ostend began serving up a beguiling mix of social pageantry and dreamy ocean reveries to cosmopolitan vacationers early in the 19th century. Elegant hotels and cafés sprang up to accommodate the many thousands of visitors who traveled there each year, primarily from Germany and other landlocked nations of Europe’s interior. Horse racing, casino gambling, splendid displays of fashion on the promenade, and a busy schedule of colorful festivals heightened the resort’s appeal. The sea itself gained renown for its mesmerizing luminosity, which some attributed to the presence of innumerable mollusks.

In 1902, when the Viennese author Stefan Zweig was only 21 years old, he wrote one of his first travel pieces about “the season” at Ostend. This affectionate caricature observes that while people typically visit watering places for “harmonious relaxation in the calm contemplation of nature,” Ostend’s clientele was different. Rather than an opportunity to switch off, its visitors sought “another shining link in the endless chain of society’s distractions.” The city had become

the unofficial rendezvous-location for the real and bogus aristocracy that one sees floating like a spume above the waves of capitals, everywhere encountering and recognizing itself, and for whom a home-town is merely a station in transit.

At season’s end, the town was returned to the fishermen and fell into a deep slumber until the “unique, unforgettable game of human fallibility, passions and distractions” began again.

Ostend: Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, and the Summer Before the Dark, German literary journalist Volker Weidermann’s artful portrait of Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, and other Central European writer-intellectuals on the eve of the Second World War centers around a summer in Ostend in 1936, during which a “real and bogus aristocracy” of intellectuals converged on this resort: writers, communists, cranky prophets, most of them Jewish. They act out the same kinds of psychological games that occupied their titled predecessors—love affairs, temper fits, exhibitions of beauty and wit—but with the suspicion that the real game is over and they’ve already lost.

The German writer Irmgard Keun turns up, after boldly suing the Gestapo for lost earnings caused by their ban on her sexually frank and socioeconomically penetrating novels. She quickly becomes romantically entangled with the much older Galicia-born author Joseph Roth; their tender liaison provides one thread of Weidermann’s story. Hermann Kesten, the socially ubiquitous writer and raconteur, arrives and finds ample material among his posturing, disoriented friends. Ernst Toller, an illustrious, politically radical, yet domestically possessive playwright, comes with his wife, the glamorous young actress Christiane Grautoff, and tries to block her path to temptation. Even the irrepressible Arthur Koestler, then gaining a reputation for his stirring, partisan journalism, appears in nearby Bredene, working on a sequel to Jaroslav Hašek’s satirical masterwork, The Good Soldier Švejk.

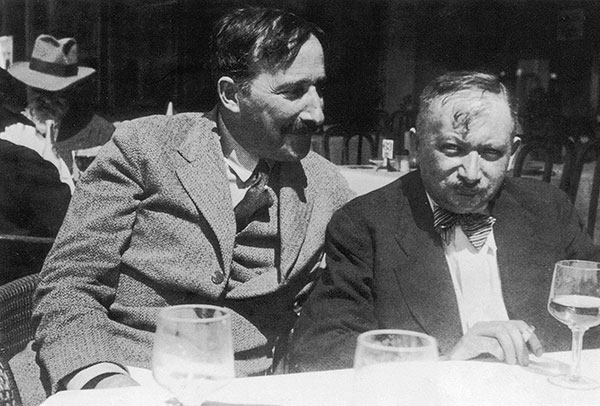

Many intriguing figures make cameos, but the axis of the book is the relationship between Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth. The sharp contrasts and strong bond between the two men make them irresistible dramatic foils. Born in the small town of Brody at the eastern edge of Galicia in 1894, 13 years after Zweig entered the world at the epicenter of Vienna’s First District, Joseph Roth scrambled and fought to make his name. He observed and dissected individual foibles and the structures of power. Zweig’s struggle, more often than not, was against his own privileged comfort and toward a shimmery realm of authenticity in art, love, and international humanism. Zweig was tallish, ultra-refined, and the epitome of genteel self-discipline. Roth was short, schlumpy, and a chronic alcoholic.

When Roth first walked by Zweig’s apartment building in 1913 to catch a glimpse of the leading light of Austrian literature, he stood shyly before Zweig’s front door for a time, then turned away and hurried home. But when Zweig became aware of Roth’s work, he recognized the younger man’s genius immediately. As he would do for many other struggling, talented authors, Zweig shared his connections and financial resources to help the outsider find a literary foothold.

By 1936, Roth’s alcoholism was increasingly desperate, and their friendship was frayed. (Roth also disapproved of Zweig’s having left his first wife, Friderike, for his former secretary, Lotte, who was with him in Ostend.) But still that summer gave them an opportunity to recover something of their old friendship. And Weidermann nicely sketches how, when Zweig became blocked in his work on The Buried Menorah, an allegorical tale about Jewish exile and homelessness, Roth was able to supply him with the story’s ending.

Weidermann convincingly shows how all these refugees were at least semi-aware that this time the Ostend season might not return. Most of them were trying to tamp down intimations of impending disaster. Germany’s book market was now shut to them. All works by Jews and others labeled “degenerates” had been burned or locked away in the so-called poison cabinet. Even when these gifted artists didn’t much like each other—as was not infrequently the case—they needed each other’s company in order to believe they still mattered.

It’s not really the summer before the dark we get a glimpse of in Weidermann’s quick, yet compelling riffle through this stack of oversized personalities. The dark had already come, three years earlier, with Hitler’s appointment to Germany’s chancellorship. What Weidermann depicts is the summer before people fully opened their eyes to the darkness that was already engulfing them. Everyone is agitated and afraid but unsure about what move to make next. In a review Zweig wrote in 1936 of his friend Roger Martin du Gard’s L’Été 1914 (Summer 1914) he observes that the heroic aspects of Europe in 1914 would not be repeated. Their own times would furnish only “the document of an immeasurable collective fatigue and of an indifference, no longer explicable by logic, to our own destruction.”

In a series of well-chosen, interwoven vignettes, Weidermann shows us this cast of extraordinary personalities struggling at once not to succumb to despair at what they already know, nor to deny in cowardly fashion what they sense is coming next. It’s an impossible balancing act. Already that spring, Zweig had written Roth, “My instinct for political calamity pains me like an inflamed nerve. I fear for Austria, and the loss of Austria would be the end of us, spiritually.” Yet they can’t quite let go of the hope that they will wake from the nightmare. Encouraging Roth to join him in Ostend, Zweig wrote beseechingly:

It would be wonderful to have you there as a sort of literary conscience [. . .] We could test one another in the evenings, and lecture each other, as in the good old days. You don’t have to swim, I won’t be swimming either—Ostend isn’t a spa, but a CITY, prettier, and with more cafés than Brussels.

True to his youthful sketch of the town, the Ostend Zweig longs for is not an escape from civilization into nature, but something closer to the reverse—a glittering distillation of civilization into its most culturally desirable essence.

Inevitably the yearning to make the resort a kind of stage on which they resume their old roles had only limited success. Some, including Zweig and Roth, were more artistically productive in Ostend than they’d been in a long time, but, of course, they couldn’t really reconstellate a whole society between them. One of the most affecting scenes in the book unfolds around a discussion that takes place one day when Zweig, Kesten, and others are all sitting at a café doing their best to assume the attitude of nonchalant vacationers. The émigrés begin to muse about the probable fate of Etkar André, a communist arrested on ludicrously flimsy evidence for treason in connection with the Reichstag fire. “What is there to say?” Weidermann writes. “None of them doubts that the sentence [of death] will be carried out [. . .] The only thing is not to show despondency. Defeatism is a crime here at the shore. It’s better to bitch around together. The later the evening, the greater the sniping, the laughter, and the mocking.” It’s a persuasive image of a particular form of distraction at which these hyper-articulate people excelled: gambling, dreaming, and promenading with words.

Ostend rises and falls in a fast, far-reaching tumble, like a low wave on a long coastline. The premise of one summer of overlapping fates is a literary device, and there is a lot of movement forward and backward in time in the book. But Weidermann has a light enough touch that we don’t feel pulled back and forth; the conceit of this 1936 sojourn gives us something solid to clutch onto. The one jarring note occurs in the book’s final section when Weidermann makes the understandable but unsatisfying move to show us the place that was once and is no longer Ostend on a trip he himself made in 2012. A present-day bar on the site of what had been a favorite restaurant of the refugees is stereotypically dreary, complete with a sound system playing American rock and roll. But Weidermann’s focus was always on his ensemble of émigrés, not their setting, and it’s hard to feel much about what Ostend has become when it was only ever shown as the faintest flicker.

The story’s real denouement appears in the passage preceding that contemporary update:

When Joseph Roth gets the news in Paris in May 1939 that Ernst Toller has committed suicide [. . .] he breaks down. Friderike Zweig, who’s with him, has him taken to a hospital where he dies a few days later. Stefan Zweig hears of this in London [. . .] “We will not grow old, we exiles,” he writes, shattered. “I loved him like a brother.”

Zweig himself committed suicide with his second wife Lotte in Petrópolis, Brazil, less than three years later, in 1942. Having struggled for years to escape his intimation that the world was ending, his sense that he was already living, as he said, “a posthumous existence,” he surrendered what remained of his life without remorse. Weidermann gives us postscripts for the other characters too, but they feel a bit perfunctory, like wrap-up lines after a movie telling us what’s become of its fictional characters. The roll-call feels out of place here, given the book’s real achievement. Weidermann has created a poignant biographical collage, stripped of most historical context, about people in the process of being stripped of all geopolitical context by the new, totalitarian state. Their voices are vivid, but we feel the characters dissolving before our eyes.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Original Sins

John Judis book about Truman's Middle East policy isn't a rant, but it's not exactly history either.

Torah and the Thermodynamics of Life: An Interview with Jeremy England

Hailed by some as the next Darwin, immortalized as a character in a Dan Brown novel, Jeremy England discusses religion and science, his background, and his intellectual influences.

Life in Learning

The special relationship between Jews and learning has been endlessly documented. Yet these investigations have largely overlooked the textual communion that transubstantiates books and learning into the body and blood of Jewish experience.

Friendly Fire: A Response and Rejoinder

Peter Berkowitz responds to Jeremy Rabkin.

navins

This is a beautiful review. Both of the authors were writers of unforgettable literature; they shared a painful end-of-life story; I had no idea they knew each other.

Now to read the book!

Nora Klein, MD

mark.scheunemann

Dr. Klein, I agree. I had no idea there was such a place with such a gathering of intellectuals and artists. The sense of impending doom, loss of all that is important, and how to deal with it is palpable.