Muscular Judaism

The best known Jew in late-Georgian London was neither a rabbi nor a banker but a celebrated bare-knuckle prizefighter named Daniel Mendoza, who was born in 1764 and died in 1836. The son of respectable, but poor, British-born parents of converso background, Mendoza grew up in Aldgate, in the easternmost part of the City of London. He was educated at the school of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue until age 13, when he was apprenticed to a glassmaker. He never completed his apprenticeship, however, and drifted from job to job, working variously for a fruit seller, a tea dealer, a tobacconist, a candy maker, a baker, and even a smuggler.

As a young man, Mendoza was quick to take offense and often resorted to his fists to answer insults and settle accounts. This was not exceptional in the rough-and-tumble world of 18th-century London, but it did make it hard to hold a job. He fought his first professional fight in 1780 at age 15 and from then on made his living from prizefighting in one way or another. The most important matches he fought were three bouts with his one-time mentor and later bitter rival Richard Humphries (or Humphreys) in 1788, 1789, and 1790. His victories in the second and third of these matches left him the undisputed British champion.

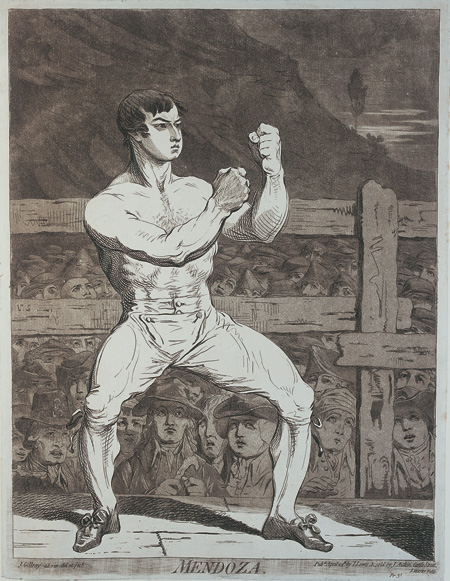

Mendoza’s fights were widely reported in the newspapers of the day, often round by round (bouts of 60 or 70 rounds were not unusual). The trenchant political caricaturist James Gillray also captured the three championship fights with Humphries, and these illustrations, as well as his full-length, fists-up portrait of Mendoza in the ring, were sold at Hannah Humphrey’s well-known print shop in London. A Staffordshire pottery produced a jug portraying the Mendoza-Humphries fight of 1788, an example of which is on exhibit at The Jewish Museum in London.

Even before Mendoza retired from the ring, he exploited his celebrity. He opened a boxing academy in London, gave private lessons to gentlemen, and toured the provinces, exhibiting the poses and tactics of famous boxers of the day. In 1789 he published The Art of Boxing and in 1816 his memoirs. Toward the end of his life, he was landlord of the Royal Oak pub on Whitechapel Road, where he presided as a kind of elder statesman over a younger generation of Jewish prizefighters.

Like many celebrity athletes, Mendoza was not good with money. He made a small fortune in the ring but quickly dissipated it in drinking, gambling, and (probably) whoring. Frequently hounded by creditors, he spent at least six months in debtors’ prison. To make ends meet, he often took jobs that were widely reviled. In the 1790s, he worked for a time as a sheriff’s officer, arresting debtors and other criminals, and as an army recruiting sergeant, or crimp, tracking deserters and enticing young men, by fair means or foul, to enlist. In 1809, the management of the newly rebuilt Theatre Royal in Covent Garden hired him, along with Dutch Sam and other Jewish fighters, to rough up demonstrators protesting a rise in the price of tickets and a reduction in the number of inexpensive seats, an episode that has come to be known as the Old Price Riots.

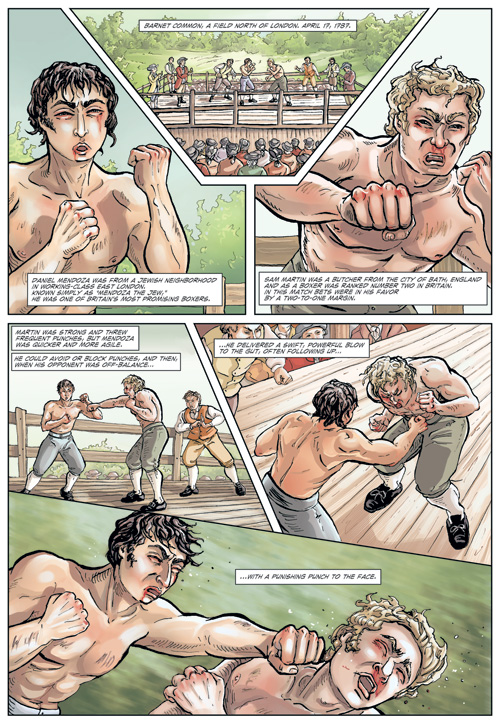

Despite the downward spiral of Mendoza’s life outside the ring, his place in the history of boxing is secure. Historians of the sport universally credit him with introducing a more “scientific” form of the sport, one emphasizing finesse and agility rather than brute strength. While opponents who were stronger than he threw punch after punch, seeking to hammer him into submission, he relied on quick footwork and exceptional balance to block or avoid their blows. Then, when his opponents were off balance, he would land a punishing blow of his own. Reporting his second contest with Humphries, the London General Evening Post described his style in this way:

The celerity with which Mendoza struck his man, exceeds all description; and was so decisive in the end that neither the superior strength and weight of Humphreys, nor the reach of his arm, could defend him from the lightning of Mendoza’s wrist.

Like Humphries, Mendoza’s opponents frequently towered over him—he stood only 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed 160 pounds. As a middleweight fighting heavyweights (there were no weight divisions then), swiftness, agility, and quick-wittedness were his most important assets.

It is easy to dismiss the career of Mendoza as just a colorful footnote in modern Jewish history, but this would be a mistake. The history of Jewish boxers in England is as central to understanding the entry of Jews into European society as the better-known and much-researched history of Jewish salonnières and intellectuals in Berlin and Vienna who were Mendoza’s contemporaries. Jewish boxers in late-Georgian London, as their accomplishments demonstrate, were as acculturated to the cultural and social norms of their time, place, and rank as Jewish salon hostesses, such as Rahel Varnhagen, were to theirs. If the entry of Jews into new spheres of activity is a hallmark of Jewish modernity, it is hard to think of a more dramatic example. More importantly, while the salonnières failed to achieve the recognition they craved—most eventually left the Jewish fold and became Christians, a testimony to the illiberality of old-regime Central European societies—the Jewish boxers were unambiguously successful even as they remained Jews. Their pugilistic skills earned them the respect and friendship of Englishmen from a wide swathe of society. The Prince of Wales (the future George IV), for one, was an enthusiastic supporter of prizefighting who bet heavily and often on Mendoza.

Prizefighting was the English national sport and Mendoza was a national hero, not just a Jewish hero, however stigmatized Jewishness was in other social and cultural contexts. One sign of his acceptance in English society is that almost all of the 300-plus subscribers to his 1816 memoir were Christians. By my count, less than 15 were Jews. (One of the few Jewish subscribers was the financier Abraham Goldsmid; another was the moneylender, political radical, and rogue “Jew” King, John King, born Jacob Rey.)

Together with artist Liz Clarke, Ronald Schechter, who teaches European history at the College of William & Mary, has produced an innovative new “graphic history” of Daniel Mendoza, which is, in more or less equal parts, a textbook for undergraduate students of British and European history, a historical novel, and a comic book. Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism also includes 50 pages of primary sources (mostly newspaper reports of boxing matches), several short essays on the historical context in which Mendoza’s story unfolded (for example, the place of boxing in 18th-century British society), and suggestions for writing assignments on related topics. It also includes an account of how Schechter became interested in Mendoza and how his collaboration with Clarke worked.

Schechter’s graphic history incorporates an interpretive argument about the path of Mendoza’s acceptance. He points out that boxing became identified with the essence of Britishness at a time when British national identity was taking shape. This occurred in the quarter century between the French Revolution and the Battle of Waterloo, when the British were almost constantly at war with the French, who became a useful foil for self-definition. The British boasted that other nations—and the effeminate French, in particular—settled their differences by dueling with pistols or swords, while the British did so in a more vigorous and manly (but less dangerous) way, with their bare fists. Britons who celebrated and befriended Mendoza considered him one of theirs because he literally embodied their ideal of masculinity.

At the same time, Schechter notes, Mendoza’s Jewishness also loomed large. When Mendoza fought, he was always billed as “Mendoza the Jew.” Gillray’s etching of the second Mendoza-Humphries match bore an inscription comparing Mendoza’s victory to the polemical triumphs of the Anglo-Jewish apologist David Levi in his exchanges with the Unitarian minister Joseph Priestley. The Christian pugilist, went the inscription, proved himself “as inferior to the Jewish Hero as Dr. Priestley when oppos’d to the Rabbi David Levi.” The Jewish prizefighters who followed Mendoza were often described similarly. When Aby Belasco met Patrick Halton in 1823, one journal referred to the match as “Pork and Potatoes, or Ireland versus Judea.” Matches like these served as a rallying point for expressions of Jewish pride. According to one report, one thousand Jews were present at the first Mendoza-Humphries fight in 1788. London’s Jewish prizefighters were, then, simultaneously British, manly, and Jewish.

One obvious downside of the graphic format is its schematic brevity. It cannot convey the messy complexity of cultural life and social behavior in the ways that conventional forms of historical narrative do. Schechter is well aware of this, which is why half of the book reads like a conventional undergraduate textbook. He is also frank about taking liberties to conform to the genre, including creating dialogue for speech bubbles. Although Schechter works to make Mendoza’s words agree with views he expressed in letters to newspapers and in his memoir and boxing manual, at times Mendoza sounds remarkably contemporary. For example, when his wife, Esther, chides him for spending money on fine clothing as quickly as he earns it, he replies: “I know, I know. I just want us to rise up in society.” Such anachronisms must have been almost impossible to avoid. Still they strike an odd note.

Graphic history must also pass muster in regard to the basic historical information it presents. Schechter’s account, while true to what is known about Mendoza, stumbles occasionally when it comes to Jewish and English history. In his treatment of the origins of the readmission of Jews to England, he mistakenly writes that Portugal expelled its Jews in 1497, when in fact it forcibly converted them en masse that year, a difference that was critical to the survival of crypto-Judaism. When he describes the Judaism of the conversos who remained in Spain and Portugal, the panel confusingly depicts a group of men, tallitot pulled over their heads, sitting at a table set with dinner plates, reading from books set before them. Perhaps they are meant to be celebrating Passover, but, if so, why are they wearing tallitot and why is there a lit hanukkiah in the corner? The Jew who peers through an opening in the window slit to check for the approach of strangers conjures up descriptions of crypto-Judaism that historians discredited decades ago. Schechter and Clarke also mishandle London’s geography. The Jews of Georgian London lived mostly in the easternmost parishes of the City of London (the square-mile, self-governing, business and financial center of London) and in adjacent neighborhoods to the east of the City. On the map of “Mendoza’s London” opposite the title page, however, the City of London and streets both north and east of the City are mistakenly labelled “the East End,” a term that was not in use at the time and that never included the City. In the Anglo-Jewish context “the East End” functions like “the Lower East Side” in America, evoking the Yiddish-speaking milieu of East European Jewish settlement in the late 19th and early 20th century.

While the East End of London (like the Lower East Side) produced its own Jewish prizefighters in the early and mid-20th century—Harry Mizler, Ted “Kid” Lewis, and Jack “Kid” Berg were the most celebrated—they were products of a very different environment than that of Daniel Mendoza. Mendoza was not an “East End” Jew, but, as Schechter shows, a third-generation English-speaking Jew, whose success in the ring earned him widespread acclaim and acceptance. In his own way, he was as much an 18th-century pioneer of the modernization of the Jewish people as Rahel Varnhagen or even Moses Mendelssohn.

Suggested Reading

The Language of Tradition

On tradition as a first language.

Faith in Princes

That FDR could have done more for the Jews in the Holocaust has long been known, but have we fully understood how much his inaction sprang from his own antisemitism?

Lucky Grossman

Vasily Grossman was one of the principal voices of anti-Nazi resistance, and a legendary journalist who spent 1000 days at the front during World War II.

The Vanishing Point

A new exhibit explores the vanished world and unseen photographs of Roman Vishniac.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In