Warped Fantasies

This summer, South Africa’s ruling African National Congress party, which has not a word of criticism to spare for its close human rights–violating allies, Russia and China, condemned Israel’s “barbaric attacks on the defenceless Palestinian people of Gaza.” Recalling the “atrocities of Nazi Germany,” the ANC’s statement asked “the people of Israel [whether] . . . ‘lest we forget’ [has] lost it[s] meaning.” For those too dense to get it, the ANC added that Israel has “turned the occupied territories of Palestine into permanent death camps.” Hamas, the missiles it was firing indiscriminately at Israeli population centers, and its exterminationist charter went unmentioned.

We are too used to this: the obscene comparison of the Jewish state and only the Jewish state to the Nazi regime; the morally and prudentially obtuse refusal to take seriously the claims of armed groups who say they want to kill Jews; the distorting “paradigm of Jewish power,” as Ben Cohen puts it, “that does not allow for Jewish vulnerability, only Jewish aggression.” Cohen, the author of Some of My Best Friends: A Journey Through Twenty-First Century Antisemitism, writes on Jewish matters for Commentary, Tablet, The Huffington Post, and other outlets. Some of My Best Friends is a collection of previously published writings.

Jews observing the resurgence of anti-Semitism in the 21st century may be forgiven for thinking that they inhabit “a warped fantasy.” Cohen applies this description to the movement to ban circumcision in “Germany—Germany!—less than a century after the Nuremberg Laws, Kristallnacht, and the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews.” But the cumulative effect of Some of My Best Friends should be to leave even skeptical readers convinced that a variety of anti-Semitism has warped much of our discourse concerning Israel and the Jews. This “ostensibly reasonable antisemitism” often goes under the name “anti-Zionism” and appeals to progressives, who angrily insist that the accusation of anti-Semitism is a smear designed “to blunt criticism of the State of Israel.” Cohen follows this partially disguised anti-Semitism from South Africa, to the Middle East, to Venezuela, to America’s college campuses. But let two of Cohen’s examples suffice to show that what he calls “bistro” anti-Semitism, in contrast to the crude, violent “bierkeller” anti-Semitism associated with Nazism, is both mad and, increasingly, mainstream.

In 2004, Ken Livingstone, then mayor of London, embraced the Egyptian cleric Yusuf al Qaradawi, who was already on record proclaiming that there can be no dialogue with Jews “except by the sword and the rifle.” He had also, the year before, reportedly issued a fatwa justifying the targeting of pregnant Israeli women and their unborn children, on the grounds that those children would grow up to be soldiers. In a world unwarped by anti-Semitism, Livingstone would have been compelled, in the face of the ensuing criticism, to choose between apologizing and losing his political standing. In the world we find ourselves in, Livingstone did indeed apologize—to Qaradawi! He dismissed Qaradawi’s critics as Islamophobes, fingered Mossad for participating in the campaign against Qaradawi, and called Qaradawi “the most powerfully progressive force for change and for engaging Islam with western values.” Livingstone went on to stand as Labour’s candidate for mayor in 2008 and 2012.

In 2011, Sarah Schulman, a Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at the College of Staten Island, took to the pages of The New York Times to discuss Israel’s treatment of homosexuality. Israel, Cohen observes, “is the only country in the Middle East where lesbians and gay men can live openly and safely engage with their sexuality.” But Schulman wanted to warn of “pinkwashing,” “a deliberate strategy to conceal the continuing violations of Palestinians’ human rights behind an image of modernity signified by Israeli gay life.” Anti-pinkwashing activists (yes, it’s an actual movement) think not only that Israel must receive no credit for gay-friendly policies but also that Israel is the cause of the persecution of gays in the Middle East. As a delegation of intellectuals who visited the West Bank in 2012 explained in an open letter, “heterosexism and sexism [are] colonial projects.” Indeed, it is offensive even to ask whether gays and lesbians can live openly in the West Bank and Gaza. According to the Palestinian queer activist Ghaith Hilal, “the notion of coming out . . . is a strategy that has been adopted by some LGBT activists in the global north. . . . Imposing this strategy on the rest of the world . . . is a colonial project.” The best thing we can do for gays who are persecuted in the Middle East is to boycott Israel. In a world unwarped by anti-Semitism, this campaign would be a skit on Saturday Night Live. In the world we find ourselves in, the Seattle LGBT Commission, “an official body that advises the city’s mayor and council on the gay community’s concerns,” dutifully refused to meet with a delegation of Israeli gay and lesbian activists, there to “exchange ideas on how to best manage issues like teenage suicides and HIV prevention,” because the Israeli consulate was among the trip’s sponsors.

Anti-Semitism, Cohen argues, is not “just another form of bigotry,” and it need not entail personal animosity toward Jews. We can take Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, the musical darling of the boycott Israel movement, at his word when he says, without irony, that he has “many very close Jewish friends.” Perhaps these friends even listen sympathetically when Waters explains why the boycott movement is a hard sell in the United States: The “Jewish lobby is extraordinarily powerful here and particularly in the industry that I work in.” Perhaps they nod along when he adds that he has “spoken to people who are terrified. . . . They have said to me ‘aren’t you worried for your life?’ and I go ‘No, I’m not.’” But whatever Waters’ personal relationships with Jews may be, he is without a doubt immersed in a paranoid delusion about Jewish power. His attempt to explain the complicated matter of what makes people hold different views about Israel by invoking a powerful lobby that has frightened or blinded almost everyone is a small-bore version of what Cohen takes anti-Semitism to be, “a method of explaining why the world is as it is” by means of the “genuinely held belief that our planet is in the grips of a Jewish conspiracy.” To date, no one in the boycott movement has so much as distanced himself from Waters’ remarks.

Cohen sees left-wing anti-Semitism as proceeding through two stages. In the first stage, which predates Zionism and originates in Marx, Jews move world history through their “distinctive function within a system designed for the extraction of surplus value.” In the second stage, associated with the anticolonialism of Frantz Fanon and the New Left, “the Jews—as a national collective—are integral to the maintenance of American hegemony” through the “settler colonialist” project we call Israel. The development of this stage owes “much to the Soviet Union,” for which anti-Zionism was a tool of foreign and domestic policy that mingled easily with crude anti-Semitism. Cohen argues that the Soviets are of special help in understanding the apartheid analogy that is ubiquitous in anti-Israel politics. It “was, in fact, the Soviet Union that established the analogy, by linking the Palestinian and black South African struggles in its propaganda.” Naive observers may be tempted to think the ANC’s dispatches deserve special notice because of South Africa’s experience with apartheid, but “the ANC, which always oriented itself to the Soviet bloc . . . has not discarded . . . Soviet ideological baggage. That commitment, far more than any distinctive insights generated by the experience of living with apartheid . . . explains why the country’s leaders are so willing to downplay the historic sufferings of their own people in order to batter Israel with the language of racism.”

Of course, Cohen acknowledges that criticism of Israel is not anti-Semitic. But when people more careful than Roger Waters attribute uncanny powers and dual loyalty to the “Zionist lobby” rather than the “Jewish lobby”; when the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)’s Middle East Studies Committee considers, as it did this year, 14 resolutions on the Jewish state, and none on any other country; when, in short, we notice otherwise well-meaning and decent people acting out a “warped fantasy” centered on the Jewish state, we ought seriously to consider the possibility that their politics have been warped by anti-Semitism. This proposition, hard to contest in general, should be unassailable on the left, which has made so much of latent sexism, racism, and homophobia. Yet progressives aligned with the anti-Israel movement want us to see anti-Semitism only “in the form of Mein Kampf-like screeds.” Only Jews are to be granted no deference when they think they see prejudice. As large numbers of Jews in Hungary (48 percent), France (46 percent), and Belgium (40 percent) tell the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights that they have considered emigrating “because of not feeling safe there living as a Jew,” we are still treated to brave public lectures about the suppression of brave public lectures by the well-funded lobby and its anti-Semitism smear campaign.

Although Cohen is right to point out the hypocrisies of the anti-Israeli left concerning anti-Semitism, he is in at least one instance too quick to adopt its standards. Four of the essays in Best Friends concern the demise of the Yale Initiative for the Interdisciplinary Study of Antisemitism, which Yale closed down in 2011. Cohen forthrightly concedes that “YIISA’s overall tone was highly politicized” and that “its interventions on Iran and its collaboration with Jewish defense organizations breached, in the eyes of many critics, the line between academia and advocacy.” I wish he had confined himself to observing that “the political convictions that informed YIISA’s work were no more pronounced than those prevailing” in other areas, like ethnic studies, which have explicitly sought to break down the wall between academia and social activism. That would have been enough to support his claim that YIISA was unfairly held to a standard other programs are not expected to meet. Instead, Cohen deploys precisely the argument academic boycott activists use to justify their attempts to turn our universities and scholarly associations into anti-Israel propaganda mills: Since “neutrality cannot be the point of departure” in the study of prejudice, even highly politicized programs ought not to be questioned. This argument is not only dubious—one can concede that scholarship is not “values free” without giving up on the distinction between scholarship and advocacy—but also unsound as a matter of strategy. It may have saved YIISA, which was soon replaced by the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism, but only at the cost of removing the best argument fighters against the boycott movement in academia have at their disposal, that politicizing colleges and universities undermines their scholarly and educational missions.

In this important treatment of contemporary anti-Semitism, Cohen almost always lives up to the praise he receives from Anthony Julius, a celebrated and scholarly British lawyer active in the fight against anti-Semitism. Cohen is an advocate who is “unusual in his restraint” and consequently the kind of advocate who no reader not already prejudiced beyond hope of persuasion can dismiss as a hothead. But Cohen, on rare occasions, loses his cool, most notably when he refers to an admittedly odious Jewish anti-Zionist and others like him as “collaborators.” As Cohen, a man of words, knows, collaborators are traitors and traitors, even if we spare them the most severe penalty, may just deserve to be hanged.

Let’s save that kind of language for the opposition.

Suggested Reading

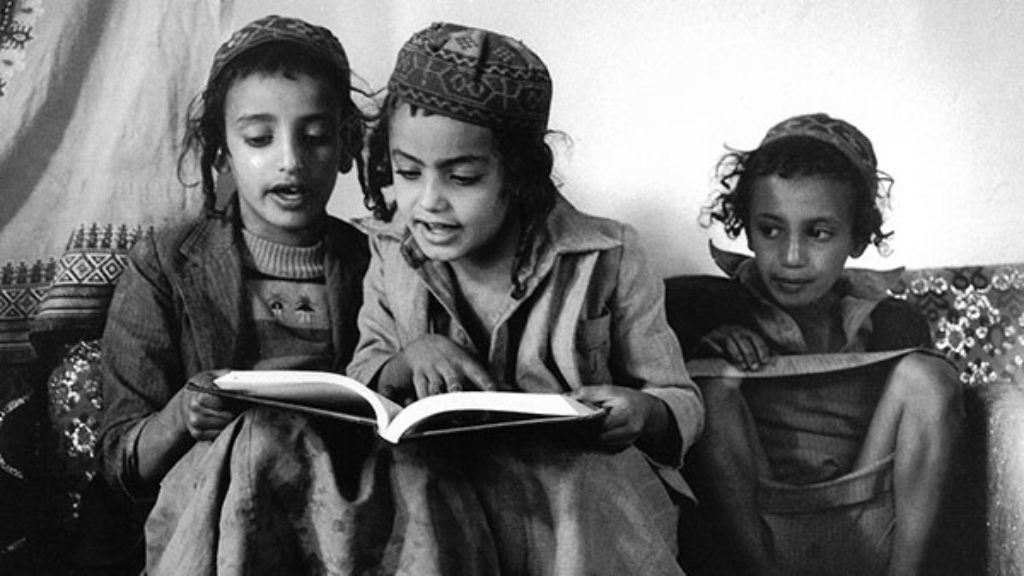

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

Melting Pot

Joan Nathan's search for Jewish cooking in France yields some surprising results.

Muddling Through

In his new book about an Upper West Side Jewish family, Joshua Henkin proves himself as a skillful writer, alternately witty and moving.

Hollywood and Jerusalem

It would be marvelous to tell you that right after the meeting I strode indignantly to my forest-green Porsche, wheeled onto the Santa Monica Freeway, sped eastward on I-10 past Palm Springs, and didn’t stop till I got to Jerusalem. But that would be untrue.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In