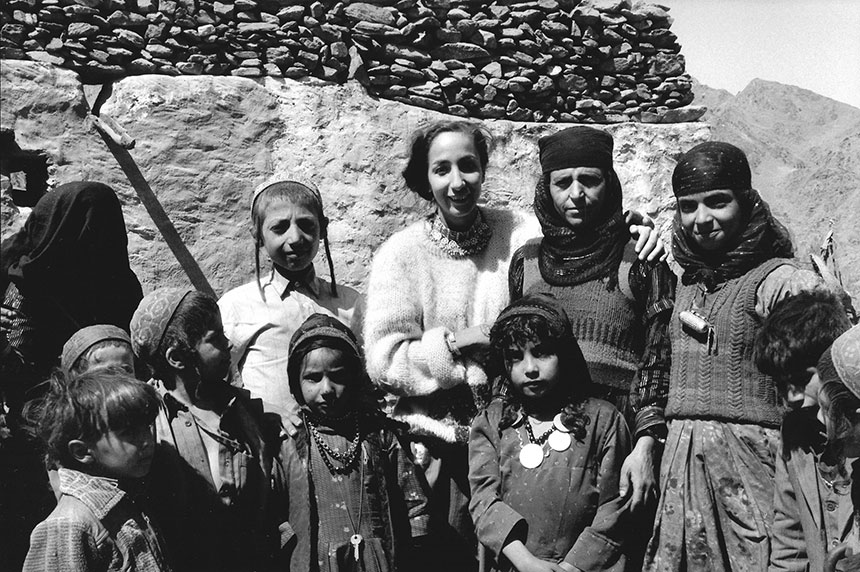

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

In 1982, I organized an evening dedicated to artists at the first Festival of Jewish Culture in France, created by the filmmaker Emil Weiss. The theme of the program was “Tradition and Modernity,” and among the artists I invited was a young photographer named Frédéric Brenner, who had just finished an as-yet unpublished series of images of Meah Shearim. Although I was primarily a painter at the time, I had already begun experimenting with photography, and I could see how extraordinary Brenner’s work was.

The next year we started traveling and

working together on what would become the 20-year “Diaspora” photography

project, which Brenner had just begun and which culminated in the Diaspora:

Homelands in Exile book and traveling

exhibition.

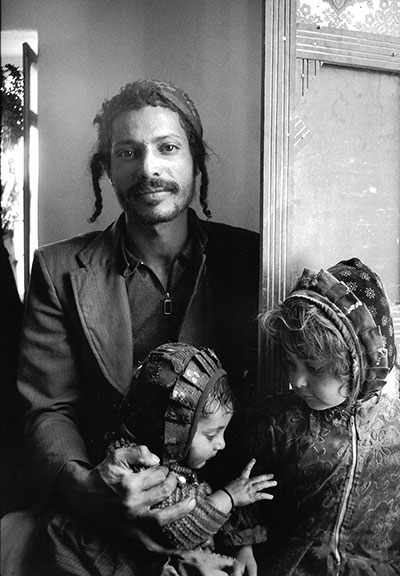

Our first trip together was to the Jewish community of Djerba, an island off the coast of Tunisia, on Sukkot in 1983. It was there that I realized that I, too, should bring my camera on these trips, first to capture Frédéric from backstage, in the act of taking pictures, but also to take photos myself. In October, when we made our first trip to Yemen, I brought my camera, as well as my paint brushes.

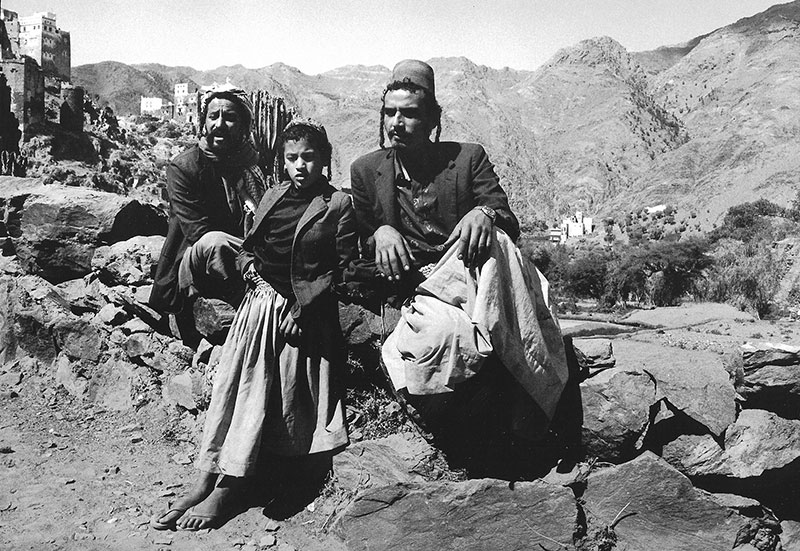

We had learned of the last Jewish communities of Yemen from the architects Pascal and Maria Marechaux, who studied the traditional earth architecture of Yemen, touring the country on a motorcycle to see the gorgeous painted houses and the unique mud-brick buildings, some of them hundreds of years old and 70 feet high. They had come across small Jewish communities here and there in their travels. These were the remnants of an ancient community that, by legend, goes back to the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon or, perhaps, to the period immediately following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. In 1949 and 1950, the vast majority of Yemenite Jews, almost 50,000 of them, had been spirited to Israel on transport planes flying out of Aden in the famous Operation Kanfei Nesharim (“On Eagle’s Wings,” an allusion to Exodus 19:4). Very little was known of those who remained, and few foreigners traveled to Yemen.

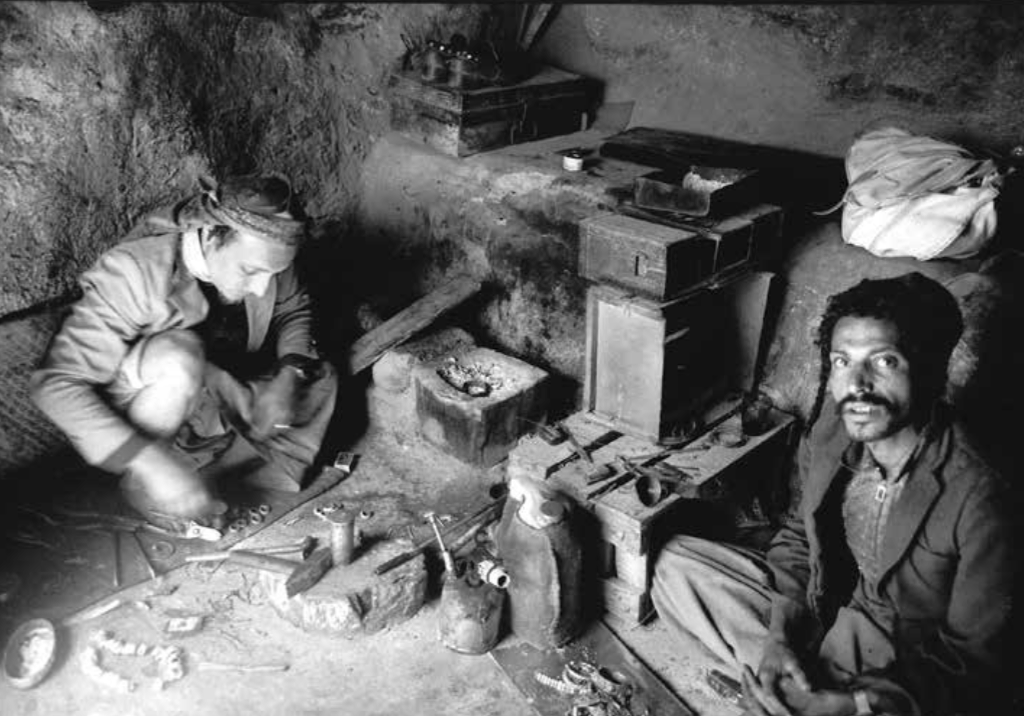

We applied for tourist visas, and, when we arrived, we made our way to different villages across the country, including Beit Sinan in the Arhab district, about an hour north of Sana’a, the capital. We could not tell our guides or hosts that we were interested in meeting Jews, both for their safety and our own. Instead, we would visit the local sheikh and ask him, through our interpreter, about his village. Since Jews were restricted to certain trades, most famously jewelry making, we would say that we wanted to buy jewelry. It was not at all surprising or suspicious that tourists would want to buy some of the exquisite silver filigree bracelets or necklaces for which these great craftsmen were famous. (Other crafts that were considered beneath Muslims and hence practiced by Jews included metalworking, leatherworking, and, among the women, basket weaving.)

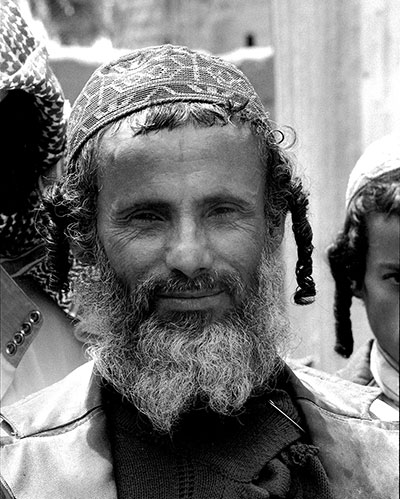

Jews had the traditional status of dhimmis, protected but decidedly second-class citizens, as non-Muslims living under Islamic law. As such, they were not allowed to own land, and, more visibly, Jewish men were not allowed to wear the janbiya, a short, curved dagger that all Yemenite Muslim men wear. Muslim men could also enter a Jewish home at any time, unannounced, except on Shabbat.

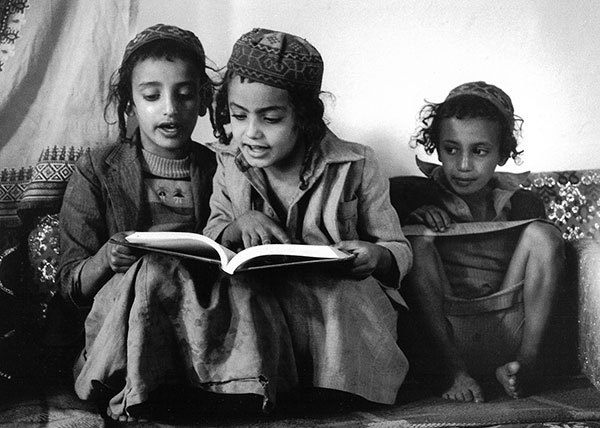

Nonetheless, the day-to-day relations between local Jews, the sheikh, and their Muslim neighbors often seemed warm, even friendly, and the pace of life was slow. From the outside, it often looked idyllic: children learning with their teacher, all sharing the same book (many learned to read upside down, a practice for which the Jewish community was apparently famous). In the long, slow afternoons, the men would talk and chew khat leaves.

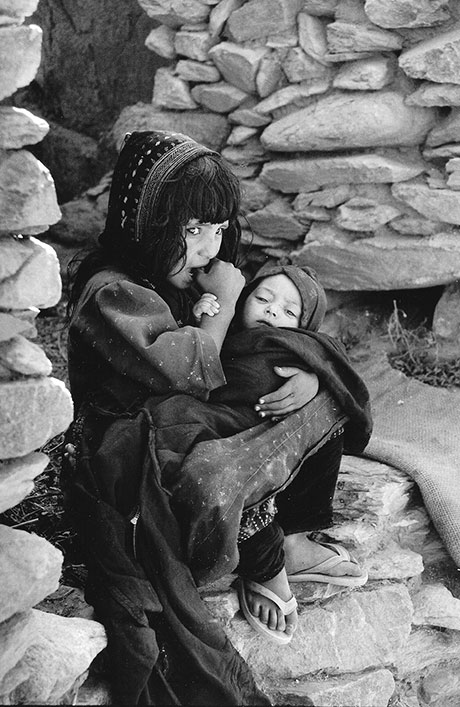

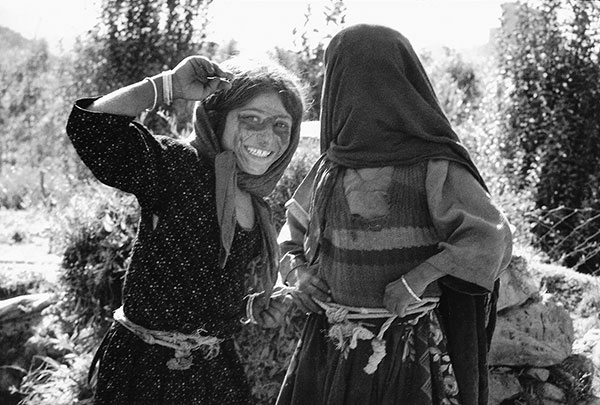

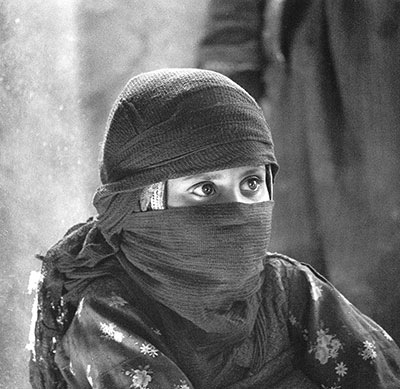

As a woman, I could spend time with the Jewish women and sometimes photograph them while they were working (cooking, sewing, making baskets) or in the home. As we traveled, we observed that the villages closer to Sana’a had stricter dress codes. The Jewish women in outlying villages did not wear a niqab, which covered the whole face, as all the Muslim women did. Instead, they wore veils that covered only their hair, but as one neared the capital, the veils grew larger.

Once, I saw a woman making a basket, and the whole scene presented itself to me, but I realized that I did not have time or space behind me to step back in order to capture both her face and her handwork in a full portrait. I quickly decided to make two linked pictures, one of her face and the other of her hands.

Unlike in Yemeni Muslim society, Jewish men and women ate together at family meals and, in general, participated more together in family life. Frédéric and I were able to share a memorable Shabbat meal with the Lewi family in “the village of the Jews,” Al Ajar. It was a four-hour drive up steep mountain roads east of the city of Saada to get there, but it was a rare and emotional moment for all of us.

After this three-week trip, we knew that we had to return. There was simply so much to see and understand of Yemenite Jewish life, its beauties and its difficulties. Moreover, photographs of this sort cannot be taken until one has established relationships, developed a rapport, and found—or failed to find—the perfect moment. Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again.

We returned during Purim 1984, and again in 1986, after our wedding. On that trip, since we did not have a translator, we decided that I would translate. I had a largely passive understanding of Judeo-Arabic from my parents, who were Moroccan Jews, and so I took a crash course in the Yemenite dialect with a professor in Jerusalem, the month before our trip. It was wonderful to speak directly with the Yemenite Jews, and since we knew the places and the people already, we spent more time just being there, waiting for the right moment to take photos. I even had time to paint.

We estimated that there were between three hundred and four hundred Jews left in Yemen when we visited. In 1992–1993, some two hundred Yemenite Jews were brought to Israel in a covert operation coordinated by the Jewish Agency. In 2016, a group from the town of Raydah and a family of five from Sana’a, in the midst of Yemen’s ongoing civil war, were also brought to Israel. It was reported that there were still some 40 to 50 Jews remaining in Yemen, living in a compound next to the American embassy in Sana’a, but it is not clear if that is still the case. The photos of Yemenite Jews that we took 30-odd years ago record a world that no longer exists.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Unfinished Rock

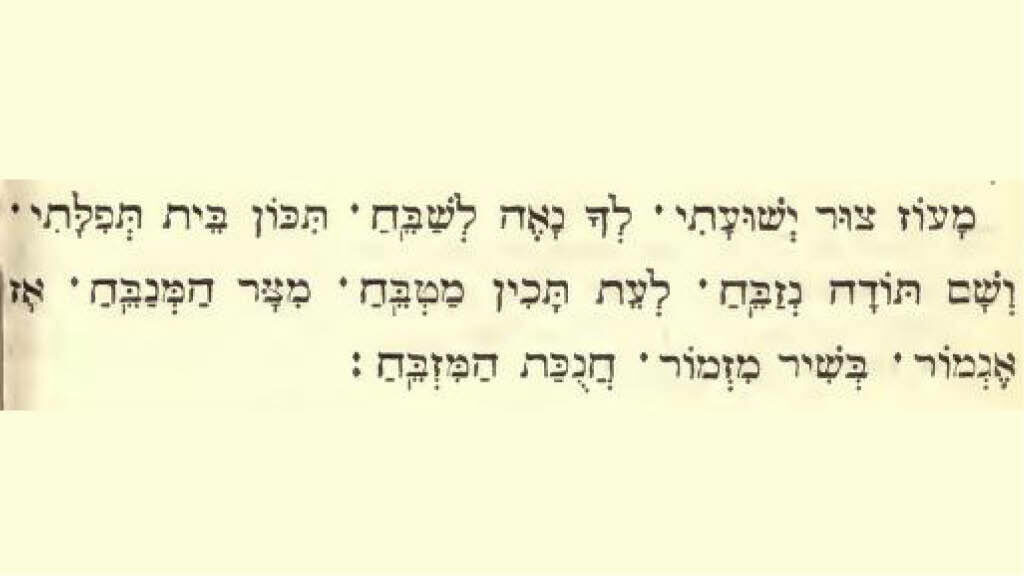

Why is the last stanza of Ma'oz Tzur unlike all other stanzas?

Welcome to Rehavia

Shababnikim, the hilarious Israeli sitcom that follows four ne’er-do-well yeshiva students, is back–and it has something serious to say too.

Her Own Creation and Pure Luck

The fraught project of becoming an American pulses through Susan Rubin Suleiman’s memoir, along with the similarly fraught project of becoming an adult.

Israel at 70: The Bonus Book List

Last week we asked 70 leading Israeli and American thinkers to recommend the best books about Israel. Here are some fascinating and quirky outtakes.

AL

Beautiful photographs. Thank you for preserving this visual record for posterity