Lands of the Free

Knowing that the Jews have recovered their homeland, however contested it remains, makes it almost as entertaining as it is painful to look back on the unsuccessful search for an alternative in the first half of the 20th century, when Palestine seemed unattainable or insufficient. It is still sad to watch the territorialists engage in their wild goose chases all over the globe at a time when multitudes of Jews were in need of a place, any place, to go. But it is also entrancing to read about the idealists and adventurers who prowled through chanceries and jungles in their efforts to outdo Theodor Herzl and his successors and find the Jews a refuge in a land that was “uninhabited or scarcely populated so as to avoid competition with the native population.”

Take, for instance, Dr. Isaac Nachman Steinberg, the man Adam Rovner describes in In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands Before Israel as “one of the most important Jewish figures of the twentieth century you’ve probably never heard of.” Steinberg was an anti-tsarist activist who did time in a Russian prison but who, when he was eventually exiled, earned a doctorate in Heidelberg for his study of criminal law in the Talmud. A leader of the non-Marxist Social Revolutionary Party during World War I, he became Lenin’s first commissar of justice after the Bolshevik Revolution:

He remained religiously observant during this period and would pray in the middle of cabinet meetings called by Lenin. “He had very discreet ways of doing it,” his son remembered. “He would get up as if to stretch his legs, lean, and cover his head with hand. But you knew he was silently running through the prayers, which he knew by heart. He never missed it.”

But he didn’t stick around long either. By March 1918 he was out of the government, and soon thereafter he fled the Soviet Union (taking with him the above-quoted son, who would grow up to become the legendary art historian Leo Steinberg).

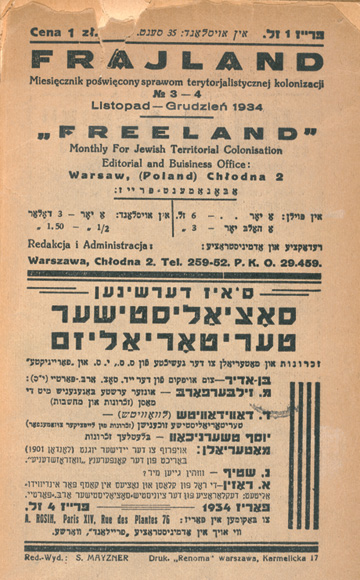

Resettled in Germany, Steinberg devoted himself to scholarship and literature (he played an important role in setting up YIVO) until Hitler took over. Fortunately, he was lecturing in London in early 1933, out of reach of the goons who were tasked with hunting down intellectuals like him. Resettled once again in the British capital, Steinberg became active in the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization, the successor to the writer-activist Israel Zangwill’s better known but by then defunct Jewish Territorial Organization (ITO), which had folded up its tent not long after the establishment of the British Mandate for Palestine.

Rovner follows in the footsteps (quite literally, with a lot of zest and a friend who took plenty of pictures) of Steinberg and the other Freelanders as they roamed large parts of Africa, Latin America, and Australia in search of a territory that would serve their purposes in the years prior to World War II, during the war, and even after the war. They achieved their greatest success in April 1947, when the Dutch governor of Suriname agreed to permit large-scale Jewish colonization “with rights of autonomy in local government” in the Saramacca district of the colony. This was too late, of course, to be of any use to the Jews threatened by Nazism, whom the Freelanders had once been desperately eager to rescue. And it was also a time when the Zionist movement, in command of world Jewry and on the brink of achieving its goals, looked askance at any plans that might divert survivors of the Holocaust from Palestine.

The prominent American Zionist leader Stephen S. Wise had played a part in helping Steinberg enter the United States in 1941 (not an easy matter for a former Soviet official). But by 1948 he regarded him as an enemy. “I personally believe,” he cabled to a friend, “that Steinberg should be lynched or hanged in quarters, if that would make his lamented demise more certain. He represents a combination of a Messiah complex and anti-Zionism, that appeals, understandably, to many Jews.” As Rovner astutely comments, “For Wise, one of the founders of the NAACP, ‘lynching’ was not an empty image.” Needless to say, nobody was strung up, but the Dutch government, apparently under Zionist pressure, seems to have compelled the local authorities in Suriname to suspend negotiations with the Freeland League at the end of 1948.

If the Zionists in fact played a part in sabotaging the Freelanders at this time, they were only fulfilling their own founder’s prophecy. He had taken notice of Freeland when it was still just a book, a utopian novel (entitled Freiland) composed by a man Rovner describes as “an educated, assimilated Jew from Budapest” and a writer for the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse with “penetrating eyes and an impressive beard.” After naming the book’s author as “Theodor Hertzka,” Rovner hastens to inform us: “That is not a typo. Improbably, Dr. Theodor Hertzka was a colleague of Dr. Theodor Herzl’s and shared with him a parallel background and professional trajectory.”

In The Jewish State, Herzl was quite eager, for obvious reasons, to distinguish his own proposals from what he considered to be the unrealistic dreams of Freiland. “Even supposing ‘Freiland societies’ were to come into existence,” he wrote, “I should look on the whole thing as a joke.” The Freeland organization that Herzl mockingly foresaw wasn’t established until the early 1930s, and although it borrowed its name from Hertzka’s novel, it did not hearken back to his specific ideas. Still, one can’t help but feel that its final defeat provided Herzl with the posthumous last laugh.

The territorialists were by no means the only Jews for whom Zion didn’t seem like an entirely adequate answer to “the Jewish Problem.” There were also the diaspora nationalists. And, as Joshua Shanes argues in his Diaspora Nationalism and Jewish Identity in Habsburg Galicia, there were Zionists who were, de facto, also diaspora nationalists. At the end of the 19th and in the early 20th centuries, the Zionism of Austrian-ruled Galicia was, he informs us:

largely a Diaspora-oriented movement, directed primarily toward national cultural work in the Diaspora (i.e., building Jewish national consciousness) and the acquisition of national minority rights, long before Zionism in either Russia or the West had begun to engage in such activity.

Galician-Jewish intellectuals came to Jewish nationalism either in the aftermath of failed attempts at integration into local, Gentile society or as part of an effort to “integrate into the modern world without abandoning their sense of authentic Jewishness.” But whatever their motives, they were not people whose lives had been shaped by the kind of pogroms or civic repression that afflicted their Russian counterparts. Living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire under a rather liberal constitution, they “felt more confident that they might achieve national rights without having to emigrate.”

The lead article published in 1895 by the young Zionist yeshiva student Mordechai Ehrenpreis (who was later to become the chief rabbi of Stockholm) in the Galician Zionists’ Yiddish-language annual is representative of the pre-Herzl period. After lamenting the extent to which Jewish children were being alienated from their own national ideals, he declared that:

We want to do what is in our power to decrease our misery, to raise our income, to multiply and increase our political rights, to improve the education of our children, to further the education and vocational training [Ausbildung] of our people [Volksmassen].

The expression of such everyday aspirations did not come at the price of building a national home in Palestine, Shanes tells us, but it definitely “tended to mean paying lip service to the settlement of the land of Israel as a long-term dream while actually focusing primarily on cultural and political work in the Diaspora.”

Just a year after Ehrenpreis published his piece—and after Theodor Herzl published his bombshell—Ehrenpreis’ colleague Adolf Korkis wrote a piece for the same journal that made “absolutely no reference to any Diaspora agenda” and declared “that the only solution to the Jewish problem in Europe was Palestine.” The Jewish State was a game-changer.

Deliverance wasn’t quickly forthcoming, however, and the older tendencies reasserted themselves, especially in the aftermath of Herzl’s diplomatic failures. Galician Zionists eventually returned to Landespolitik, Jewish domestic politics. Shanes devotes the final chapters of his book to the Zionist-led campaign to win Galician seats in the Austrian Parliament, one in which “the Zionists completely severed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine from their domestic political agenda.” His vivid account of the 1907 election campaign in which Jewish nationalist candidates competed with “assimilationists” and socialists culminates in an assessment of the nationalists’ less than grand but still impressive demonstration of political power. True, it did not result in any major victories. “The party did not succeed in achieving its major goal, the recognition of Yiddish as a legal Umgangssprache and the acquisition of national rights for Habsburg Jews.” But it did succeed in inducing sizeable numbers of Galicia’s hundreds of thousands of Jews to see themselves in the years before World War I as one of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s constituent nationalities and to demand “the rights associated with this status.”

If the Zionists of Galicia, in practice, veered toward diaspora nationalism, there were other Jews, at the same time and mostly further east, in the tsarist empire, who raised it to the level of theory. In Jews & Diaspora Nationalism: Writings on Jewish Peoplehood in Europe & the United States, Simon Rabinovitch surveys these theories. The first thinker included in this anthology, Perets Smolenskin (1842–1885), conceived of the Jews as a “spiritual nation” bound together eternally by its cultural heritage, “even if we assert that restoring sovereignty to Israel is unattainable.” While he himself was more or less prepared to make such an assertion when he launched his attack on the Haskalah in the early 1870s, Smolenskin changed his mind after the pogroms of 1881 and the emergence of the Lovers of Zion.

This change of heart did not prevent Smolenskin from being hailed as a predecessor by the leading diaspora nationalist, Simon Dubnov, who, beginning in the 1880s, presented a comprehensive picture of the Jews as a “spiritual (cultural-historical) nation” that should seek limited autonomy on the European soil where it had been so long established, as well as in countries like the United States, where it had new footholds. Like other territorial or non-territorial nations, the Jews, he maintained, “share internal connections and collective national interests”:

These mutual national interests are in practice expressed by specific forms of internal self-governance, in the independent organization of popular communal, educational, and religious institutions; in the autonomy of the school curriculum (including its linguistic autonomy); and lastly, by a united voice in parliamentary and social debates that results in distinct national policy.

Skeptical of the practicality of Zionism from the outset and irreversibly convinced that it could never provide a solution to the problems faced by the preponderant majority of Jews, Dubnov also had deeper reservations concerning the restoration of a Jewish state. He argued, as the historian Jonathan Frankel observed “that the Jewish nation, lacking a territory of its own, represented the highest form in the evolution of nationalities, dependent as it was entirely on ‘cultural-historical’ and ‘spiritual factors,’ with ‘no possibility of striving for political victories, territorial annexations or the subjugation of other peoples.’” This attempt to develop a benign nationalism is what, perhaps, makes Dubnov and his colleagues attractive to cosmopolitan idealists even today.

In addition to seminal texts of Smolenskin and Dubnov, Rabinovitch includes in his anthology excerpts from the theoretical writings of other diaspora nationalists, such as Chaim Zhitlowsky and Jacob Lestchinsky, as well as the writings of American Jewish thinkers whose work reflects Dubnov’s ideas. In his more recently published Jewish Rights, National Rites: Nationalism and Autonomy in Late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia, Rabinovitch focuses not so much on explicating theories as on attempting “to define Dubnov’s sociopolitical footprint” up to and beyond the Russian Revolution. He relates, among other things, how in 1907 Dubnov and his allies created, in a far more tumultuous environment and a much less stable state than Habsburg-ruled Galicia, the “Folkspartey,” a party that aimed to achieve three goals:

(1) a democratic Russian government with “complete equality of rights for all peoples of the empire”; (2) the legal recognition of Jewish nationality “as a single whole with rights to national self-government in all realms of internal life”; and (3) the convocation of an all-Russian Jewish national assembly, “for the purpose of establishing the principles of national organization.”

While Dubnov and his Folkspartey helped to shift Jewish politics, as Rabinovitch maintains, in the direction of increasing “Jewish collective rights,” neither they nor the other supporters of autonomism, including Russian Zionists, could achieve anything concrete in the context of a deeply anti-Semitic regime. But following the overthrow of the tsar, in February 1917, “Jews focused their political energies on creating the mechanisms of Jewish national autonomy that had been discussed in theory in the Jewish press since Simon Dubnov’s articulation of autonomism between 1897 and 1907.” The nationalist intellectuals finally had “the opportunity to turn what had been theory into action.”

In the spring of 1917 (when Isaac Nachman Steinberg still had his eyes focused on bigger things) the Jewish nationalists prepared the ground for an “all-Russian Jewish congress as the ultimate expression of Jewish autonomy in Russia,” but when elections for this congress were held in November, the Zionists won them handily. This did not necessarily represent a defeat for the Folkspartey, for, according to Rabinovitch, it is not really clear how many of its members “actually wanted power within the community rather than simply the adoption of their and Dubnov’s ideas about Jewish autonomy.” In fact, what Russian Jews did on the national level and on the level of local communal governments “must be considered a vindication of the Dubnovian worldview.” If it was a vindication, it was short-lived. Following their coup in the very month that the Russian Jewish Congress’ elections took place, the Bolsheviks, fierce opponents of Jewish nationalism, made it impossible for the Jewish people’s chosen representatives ever to assemble. What Soviet Jews enjoyed under their subsequent rule was anything but autonomy (despite the name affixed to the bogus homeland established for a few of them in the 1930s, the “Jewish Autonomous Region of Birobidzhan”). Elsewhere in Eastern Europe, after the war, the situation was better—but not much better. In Poland and Lithuania, the autonomists tried and failed to implement their program. “The idea of nonterritorial Jewish autonomy,” Rabinovitch notes in his book’s final pages, proved “incompatible with the nation-states that emerged in the post-World War I era.”

In The Tragedy of a Generation: The Rise and Fall of Jewish Nationalism in Eastern Europe, Joshua Karlip concentrates on the way in which several Russian-born supporters of autonomism, who were also secular-minded Yiddishists, came to terms with the post-war collapse of their dreams. Less than illustrious but still important intellectuals Elias Tcherikower, Isroel Efroikin, and Zelig Kalmanovitch changed from believers that the “hour of national redemption had come,” with the Russian Revolution, into people who had “largely despaired,” by the late 1930s, “of the ideologies to which they had dedicated most of their careers.” Their experiences with hostile or unsympathetic regimes, in the West as well as in the East, together with the steady “disintegration of the Jewish national collective,” led them to question not only autonomism but the benefits of the entire age of emancipation that had given rise to the idea. Breaking painfully with Dubnov, Tcherikower, for his part, issued a call in 1939 for “a return to the ghetto,” albeit a very ambivalent one.

We know that the call backward is in vain. The old sources of religious faith are very dried up, even among the common people themselves. Our generation is too far gone in skepticism, indifference, and criticism to be able to once again bind itself with tfiln straps. We long ago lost the past simplicity of religious faith, and no one has the strength to once again pour old wine into new vessels. But we also do not have the strength to free ourselves from the need for yontev; and from envy of the harmonious religious world of previous generations. We are tired of gray, rationalistic commonplaces. This is a tragedy of the generation that conducts a struggle with itself, a struggle between modernism and its own inheritance.

This perception of a tragic dilemma did not lead Tcherikower into passivity. “Although not overtly Zionist,” he envisioned a Jewish exodus from Europe that “echoed Herzl’s vision in Der Judenstaat.” He escaped from occupied France in September 1940 and settled in New York, where he continued—until his death from a heart attack in 1943—his revisionist, counter-emancipationist work in modern Jewish history.

Efroikin, who along with Dubnov played a leading role in the Folkspartey in Russia in 1917, was, Karlip writes, “more Dubnovian than Dubnov himself.” Opposing the Zionist movement on practical as well as theoretical grounds, he vaunted the Jews as a people that had “liberated its existence from the reign of a piece of land.” But the Bolshevik seizure of power in the land he considered his own soon forced him to migrate to the still-not-communist Ukraine, where the Zionists once again beat out the folkists in elections that didn’t matter for very long: “When the Ukraine fell to the Soviets in 1920, Efroikin left Russian soil forever, immigrating to Paris.”

Even as he became a wealthy businessman, Efroikin remained actively committed to diaspora nationalism. But his limited success as head of the Federation of Jewish Societies and the worsening overall situation destroyed his hopes for change. “In 1938, Efroikin visited Palestine and returned to Paris an admirer and supporter of the Labor Zionist leadership of the Yishuv” who saw Palestine as the site of a future Jewish national home. When he made his escape from France, however, in 1942, it was to Montevideo, Uruguay. In his writings from Uruguay, Efroikin developed a somewhat peculiar Zionist vision that “incorporate[d] the best elements of folkism” while repudiating the folkist argument “that understood the Jews’ status as a stateless nation as advantageous and avant-garde.”

Although he started out as something of a Zionist, Karlip’s third major figure, the philologist, translator, and editor Zelig Kalmanovitch, was for many decades a dedicated proponent of autonomism. In 1917 he dismissed the Balfour Declaration as a cynical, self-aggrandizing move on the part of British imperialists, one that would do nothing for the Jews other than embroil them in conflict with the Arabs. When Ukraine fell to the Soviets in 1920, he resettled in Lithuania. Working there, in Latvia, and ultimately in Poland (as an administrator at YIVO in Vilna) to implement the cultural program of diaspora nationalism, he eventually despaired of ever achieving any real success. After Hitler took power in Germany, he became a territorialist and joined the Freelanders. As late as 1938, he dragged Lucy Dawidowicz, then a young graduate student from America, to public meetings where he “enraptured his audience with speeches in favor of territorialism.”

Following the outbreak of World War II, Kalmanovitch “referred to the founders of the Zionist movement as ‘wise Jews and Jews with love for their people and Jews with love for their people,’ . . . [who] had predicted the possibility of such a catastrophe as early as two generations ago.” But for Kalmanovitch, it was now too late to escape to Palestine, where before the war he had been offered what he called “a spectacular position” with the National Library. His work now, under increasingly trying and eventually desperate circumstances, was to do what he could to preserve the Jewish cultural heritage. As the diary he wrote in the Vilna ghetto reveals, he found himself returning to “some aspects of biblical and rabbinic faith and theodicy.” He survived his deportation from the ghetto to forced labor camps in Estonia for only a few months. “According to survivors, Kalmanovitch went to his death addressing the following words to his German oppressors: “I laugh at you; I am not afraid of you! I have a son in the Land of Israel!”

The moral of this story might seem clear enough. As Karlip observes in his conclusion: “The State of Israel has proven Kalmanovitch, Efroikin, and Tcherikower correct in assuming that if secular Jewish national politics ever would be realized on a mass scale it would be in a future state in Palestine.”

Rabinovitch, for his part, is somewhat more tentative. “Autonomism’s greatest success,” he says, “was in the most unlikely of places: Palestine.” All the other “successes” he has in mind, in Russia and Ukraine, for instance, were admittedly very short-lived. But this, in his judgment, does not retroactively demonstrate that this is the way things had to be:

Whether autonomism and genuine national rights for Jews as a nonterritorial minority might have taken hold in Eastern Europe largely depends on how one views the historical prospects of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. The collapse of those empires, and the manner in which they collapsed, was by no means historically inevitable.

Had the Russian Revolution ended some other way, some of the abortive experiments might have proved long-lasting. To deny this, Rabinovitch argues, is “to accept the inevitability of Jewish autonomism’s failure in the remnants of the Russian Empire is to a certain extent to accept the Bolshevik historical narrative of the inevitable triumph of proletarian socialism.”

It is indeed possible, as Rabinovitch insists, to imagine a different history than the one we have had. And even for those who see little value in such counterfactual speculation, it remains interesting to discover the intricate and often surprising connections between Zionism, autonomism, and territorialism. What matters most, in the end, however, is what Rovner tells us in the very last sentences of his book: “The mythopoesis of Israel ultimately proved more potent a nationalist force than any other territory. Of all the many promised lands, only one today is real.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What’s Going On With Antisemitism?

Jonathan Karp responds to Reviel Netz

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

Talking Like That

“Their voice sounds weird, like not a Jewish voice.” How newcomers learn the language and culture of Orthodox Judaism.

A Murder in Queens

The murder conviction of Marina Borukhova in 2008 shocked the Bukharan Jewish community of Forest Hills. But many questions remain unanswered.

shimoni

As always Allan Arkush's review article is discerning and illuminating. Soon Gur Alroey's excellent book on Territorialism, "Seeking a Homeland" (in Hebrew) will appear in English translation. Hopefully, Arkush he will soon be able to add a review of that work.