A Spy’s Life

Sylvia Rafael: The Life and Death of a Mossad Spy opens not with an intrepid secret agent about to pull off a bold maneuver, as books with such titles usually do, but with nine men gathered around a table in 1977, studying a picture of an Israeli agent. “This woman must die,” orders the group’s leader, Black September terrorist Ali Hassan Salameh. Salameh had support at the highest level for this action against her, with financing personally provided by Yasser Arafat. The team had assembled in Oslo, retrieved weapons from a stash in the Libyan embassy, and prepared to launch the attack on Rafael from a public park as she left her home the following morning. The night before, the hit squad “avoided using the telephone, hid out in their rooms, made do with sandwiches, and retired early.”

After this ominous beginning, the book flashes back to the South African backwater in 1946, when a bedraggled Holocaust survivor found his way to the prosperous home of Ferdinand Rafael, Sylvia’s father, and collapsed on the doorstep as his family was enjoying tea time. In his pocket was a Soviet passport in the name of Alex Rafael and in his hand a letter, written years ago from Ferdinand in Graaff-Reinet to Alex in Kiev on the occasion of his bar mitzvah. From this newfound uncle Alex, after he was revived, young Sylvia (whose Boer mother had never converted but fasted on Yom Kippur) received the beginnings of her Jewish education. He told her both Bible stories and the tale of his own miraculous escape from the deadly pit at Babi Yar where his entire family (including his own daughter, Sylvia’s age) had been murdered. She put things in her own words in a school essay:

Our entire family in Europe was killed before we had a chance to meet them. My father told me that they were very nice people . . . They were taken from their houses and killed, just because they were Jews. The Ukrainians and the Germans had rifles and cannons, but my family didn’t even have a revolver to protect them . . . I asked my father why God didn’t protect his Jews, why didn’t He save our family, and Father only said: If the Jews don’t defend themselves, nobody else will do it for them.

History had made its mark on her.

As they tell Sylvia Rafael’s story, co-authors Moti Kfir and Ram Oren (a writer of best-selling Hebrew thrillers) also trace the life story of her eventual nemesis, Ali Hassan Salameh, cutting back and forth between the two. In 1948, as Sylvia was delving deeper into her Jewish heritage, Ali, who was three years younger, was with his father, Hassan Salameh, on the road to Jerusalem, watching a Jewish convoy approach and grind to a stop as it met the roadblock his father’s men had prepared: fallen rocks and a booby-trapped dead dog. Ali watched as Hassan ordered the attack, preventing the convoy from reaching the besieged city of Jerusalem. He stayed at the roadblock, watching more ambushes, more death on both sides, for two days. It was all part of Ali’s training to follow in his father’s footsteps. “For the Jews of pre-state Palestine, Hassan Salameh’s name was synonymous with destruction and annihilation,” Kfir and Oren write. Earlier in the decade, Salameh had been the senior aide of the exiled Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, in Nazi Germany.

When Israel declared its independence, Sylvia hoisted the flag of the new state in front of her family’s home. Wounded in the June 1948 battle at Ras al Ayn, the dying Hassan Salameh made his wife and young son promise Ali would carry on the struggle against the Jewish presence in Palestine.

When she was 22, Sylvia Rafael moved to Israel, leaving behind a family that, with the exception of her mother, neither understood nor supported her decision to abandon a promising young lawyer who wanted to marry her and a comfortable life in South Africa. For a while, she wandered, working first as a volunteer on a kibbutz and then as an English teacher in Holon, unsatisfied with the work but unable to find anything that quite suited her. Then, as is the norm in elite Israeli units, where “a friend brings a friend,” the Israeli secret service, specifically the ultra-clandestine Unit 188 that performed covert operations outside of Israel, found her:

Sylvia’s roommate, Hannah, had a friend named Zvika, who was an instructor at the unit’s School for Special Operations. During one of his visits to the flat, Zvika was introduced to Sylvia and had a long conversation with her. He was impressed by her intelligence, her native English, and her burning desire to serve the State of Israel.

“I think she could be right for us,” he told his colleague, the commander of the School for Special Operations.

Rafael soon had a cloak-and-dagger meeting with “Gadi,” an interview for a job he could only describe as “a hugely challenging job involving quite a lot of travel abroad” with an organization he couldn’t name. Gadi was in fact co-author Moti Kfir, the school commander to whom Zvika had spoken. It was an unusual dance, feeling out someone for a job you couldn’t tell her about until you were fairly sure she could do it. Kfir thought that she could and recommended she go through the unit’s initial battery of tests and psychological evaluations. She passed them all with flying colors.

Rafael continued to excel throughout her training, which covered everything from explosives to how to avoid looking like an Israeli when she peeled an orange. She mastered the business of being a spy as she began to inhabit the new persona created for her by “Yitzchak,” her mentor as she transitioned from training to operations. While at times Kfir and Oren veer close to propaganda (or hagiography) in describing Rafael’s life, their account of her mentor Yitzchak’s ability to “act any part, assume any disguise, and blend into any background” is, if anything, understated. Readers will have to turn elsewhere for the sensational details of Yitzchak’s key role in the execution in Uruguay of Herbert Zuckers, aka Herbert Cukurs, the “Hangman from Riga.”

On the other hand, they spare no superlatives as they tell how Sylvia “became” the Canadian photographer Patricia Roxenburg, charming the neighbors and making friends who could vouch for her if the need arose; how her photographic skills developed to the point where she was hired by a French photo agency and had an exhibition of her photographs from war-torn Djibouti in Paris; how she calmly withstood detention and the threat of execution in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, where she had gone, undercover, to take photographs. Although she doesn’t appear in Steven Spielberg’s Munich, readers will realize that the dramatic assassination by telephone bomb it depicts was made possible by Sylvia’s ability to get the target, Dr. Mahmoud Hamshari, out of his Paris apartment on the pretext of a newspaper interview long enough for Mossad agents to plant the bomb.

Despite his playboy ways and love of fast cars, the adult Ali Hassan Salameh made himself indispensable to Yasser Arafat and the PLO. While sources within the CIA and Black September apparently play down his importance, the Mossad was sure he had earned the moniker “the Red Prince” for his lineage and for the blood of the innocents that was on his hands. Their analysts placed him at the center of the planning not just of the massacre at the Munich Olympics in 1972, but of operations the previous year, including the hijacking of a Brussels-to-Ben Gurion Sabena airliner and coordination with the Japanese Red Army terrorist group in its deadly attack in the Ben Gurion Airport.

Sometimes Kfir and Oren strain too hard to connect Rafael and Salameh—over-emphasizing their fundamental differences as well as their similarities. It’s entirely believable that Sylvia’s Mossad file contains a note from a psychologist concerning a comment she made in one of her initial interviews: “The word ‘impossible’ doesn’t exist in my lexicon.” But do Kfir and Oren really know that, at a meeting called to plan the explosion of an El Al plane in mid-air, Ali told his incredulous co-conspirators: “The term ‘impossible’ doesn’t appear in our lexicon”? If the Mossad had either the listening capabilities to overhear such a conversation or a mole deep enough inside Fatah and Black September to report it, would Kfir, even now, reveal it? And would it have made it past “Ilan Ben David and the censorship team” or “Aryeh Zohar, Chairman of the Ministerial Book Censorship Committee,” who are thanked in the book’s acknowledgements? One wonders.

After a string of legendary successes, the Israeli hunters of the men responsible for the Munich massacre famously met with failure in Lillehammer, Norway. It was a disaster that Rafael, a member of the team, tried to avert, pointing out that the hastily assembled team had no backup plan if the operation took a bad turn. And she had her doubts, as did others, that the man they were trailing really was Ali Hassan Salameh. But her voice went unheeded, and on July 21, 1973, the Mossad murdered Ahmed Bouchiki, a Moroccan Arab, in front of his pregnant Norwegian wife as they walked home from a movie. Six of the team members were apprehended and sentenced to prison, among them Sylvia. She served two and half years of her five-year term before being released—but not back to the Mossad, and only for a time back to Israel. “Something in me broke after Lillehammer,” wrote Sylvia, who had refused an administrative position within the Mossad. “[I]t eroded my desire to continue serving with the people I respected so highly. My heroes had appeared to be men of absolute integrity, but suddenly I saw them in a different light.” Speaking some 40 years later to a Canadian radio program about Sylvia and the disaster at Lillehammer, one can hear the emotion in Moti Kfir’s voice when he says, “It was a disappointment to the state; it was a disappointment to the people who took part in it.”

After close to 200 pages of historical narrative tying Salameh and Rafael so tightly together, Oren and Kfir are left to deal somewhat awkwardly with the reality that at the end of the day Rafael was a brilliantly adept and charismatic player in a larger game that continued without her. As it turns out, Ali Hassan Salameh was something of a pawn in that “great game.” Since 1969, he had maintained, with Arafat’s knowledge, an ongoing dialogue with CIA officer Robert Ames, forming the first back-channel link between the PLO and the U.S. government. Although Salameh had never formally agreed to become a paid CIA asset, he was certainly an asset to the CIA, and the Mossad knew it.

The Mossad continued to look after Rafael, learning of and stopping the 1977 plot to kill her in Oslo, where she had moved after marrying her Norwegian defense lawyer, Annæus Schjødt. And, after inquiring whether he was under CIA protection and receiving no answer, it continued to look after Ali Hassan Salameh, tracking him down in Beirut, where on January 22, 1979, another bright, ambitious young female Mossad agent pressed the button on her explosives-packed Volkswagen, killing him. After several decades of happily married life, Sylvia Rafael died of leukemia in South Africa in 2005.

Suggested Reading

Ike’s Bet and Nasser’s Vasser

Could the hot dog-munching, movie-going young colonel named Nasser have become our man if we had tried harder to accommodate him at the very outset?

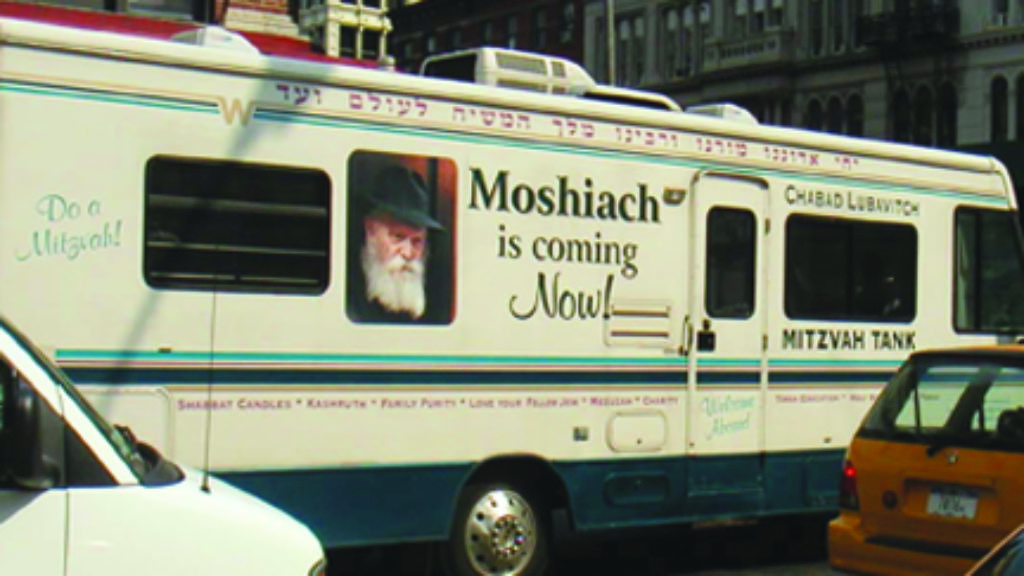

The Chabad Paradox

Despite its tiny numbers, the Hasidic group known as Chabad or Lubavitch has transformed the Jewish world. Not only the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect, it might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century. But two new books raise provocative questions about it.

Fiction and Forgiveness

Dara Horn’s novel goes down to Egypt to guide its perplexed characters through a Joseph story.

“I’m Eighty-Five Years Old, Bubba’leh”

"Feel free to also call me ‘Rabbi’ or ‘Professor.’ Neither offends me. No, not ‘Motti.’ Never ‘Motti.’ If you want to call someone Motti, why don’t you go downstairs and talk to the guy at the corner store?" An excerpt from The Ghost Editor.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In