Living Postcards

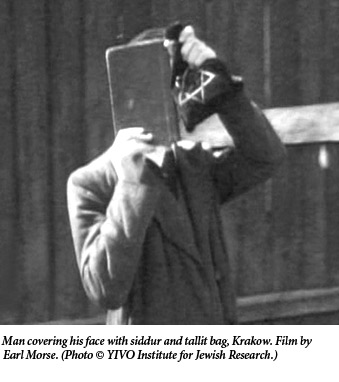

When people see a still camera, they know they are supposed to pose. When they see a movie camera, they know they are supposed to do something. Only infants and trained performers know how to act normally before the camera. The subjects of “16mm Postcards: Home Movies of American Jewish Visitors to 1930s Poland,” an exhibit at the Yeshiva University Museum, behave as they are expected to; they form into lines, wave at the camera, walk forward smiling intensely, clown around, and show off their children. A few refuse to be recorded. One covers his face with a book and a tallit bag and rapidly walks away.

There is an ethnography of gestures, and some of the performances show the differences between the natives and the visitors. Americans wave to the camera by raising their right arm and moving it from side to side; Poles wave by putting their right arm forward and flapping their hand. There seem to be differences in the way people hold themselves and move: city folk stand erect and walk briskly, while the country folk stoop a bit and do not seem to be in such a hurry.

There is an ethnography of gestures, and some of the performances show the differences between the natives and the visitors. Americans wave to the camera by raising their right arm and moving it from side to side; Poles wave by putting their right arm forward and flapping their hand. There seem to be differences in the way people hold themselves and move: city folk stand erect and walk briskly, while the country folk stoop a bit and do not seem to be in such a hurry.

The most important thing about the people caught on film in “16mm Postcards” is that they are nothing special. Not to us anyway. They may have been special to the people who took these amateur movies and to their intended audience—friends, family, Landsmannschaften—but they are displaced in this 21st-century-museum setting. It is their aura of the quotidian, however, the very sense of how ordinary they are, that makes watching them go about their paces in the stuttering movements of these simple films so fascinating.

The heart of “16mm” is four compilations, each 8 to 12 minutes long, of segments from movies taken by American visitors to Poland in the decade before the outbreak of the Second World War. The films were culled from the extensive holdings of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research by Zachary Paul Levine, assistant curator at the Yeshiva University Museum, and Jesse Cohen, YIVO’s Photo and Film Archivist. Most of the cinematographers were immigrants to America who were returning to visit their Alte Heym. (The exhibit closed in early January 2011, but the films can still be watched on the Center for Jewish History’s website.)

The films are continuously projected on the walls of the gallery so the figures appear to be about life-size. Benches are provided for the museum visitor to sit and watch, but the experience is very different from going to the movies: there is no story. It is not even like watching a documentary where there is exposition and a point of view. The compilations are ordered in loose thematic categories—Landscapes, Portraits, Candids, Panorama—but the themes tend to meld into each other. In the end, the unit of interest is the individual segment, each with its unique setting in a city, town or village, and each with its individual cast of characters.

|

|

Almost all of this is anonymous. Warsaw, Lublin, Krakow and Vilna are names with which viewers will be familiar, but how many can locate Skidl, Szedziszow, Kamionka, Skeirniewice? They are places whose existence for us depends on their having been filmed. This is even more so, and more affecting emotionally, of the people, none of whom is identified by name: they exist because on a certain day they wandered in front of the lens of a camera held by someone who had returned from America. For some of the segments, neither the cinematographer, nor the subjects, nor even the locale are known.

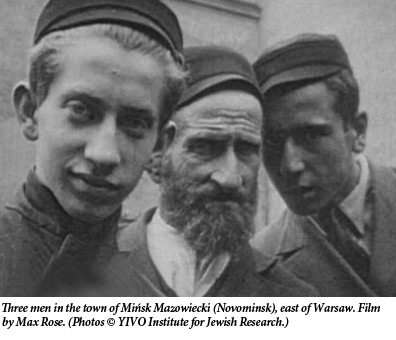

There are all sorts of Jews. Visitors to the museum who are familiar with Image Before My Eyes: A Photographic History of Jewish Life in Poland, 1864-1939 by Lucjan Dobroszycki and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, or the associated documentary by Joshua Waletzky, know how varied Polish Jewry was. There are picturesque shtetldik couples in caps and kerchiefs, and Hasidim in caftans and ankle-length skirts, but there are also city dwellers in three-piece suits and fur-trimmed coats worn with smart hats. Throughout, there are children of all varieties and in large numbers.

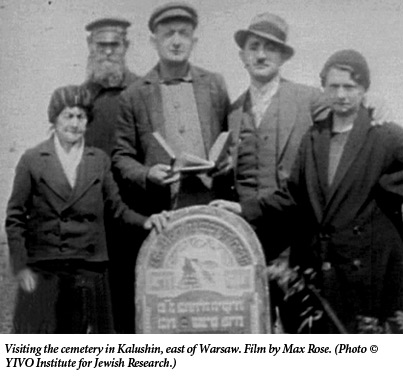

A recurring scene is a visit to the cemetery. Typically there will be a shot panning across the whole cemetery, and then close-ups so the inscriptions on particular headstones can be read. Often, there will be a sequence with the visitor saying kaddish, in one instance with tears streaming down his cheeks.

Other scenes that occur more than once are pictures of a village marketplace, children working the handle of a water pump, synagogues, horses and horse-drawn wagons, the countryside shot from the window of a moving train, the children in an orphanage or school arrayed in neat lines, the principal churches and public buildings of a city, evidences of poverty, someone being kissed, more horses and horse-drawn wagons, and, somewhat surprisingly, marching bands, some in uniform and others in civilian clothes. One wonders if they are Jewish bands, what tunes they are playing, and for what occasion.

Other scenes that occur more than once are pictures of a village marketplace, children working the handle of a water pump, synagogues, horses and horse-drawn wagons, the countryside shot from the window of a moving train, the children in an orphanage or school arrayed in neat lines, the principal churches and public buildings of a city, evidences of poverty, someone being kissed, more horses and horse-drawn wagons, and, somewhat surprisingly, marching bands, some in uniform and others in civilian clothes. One wonders if they are Jewish bands, what tunes they are playing, and for what occasion.

In one shot, a self-important chicken struts around a village. In another, a woman with only two teeth breaks into an incredible smile. And there is a shot of children surrounding a street juggler who keeps three and then four balls in the air and finally passes the hat.

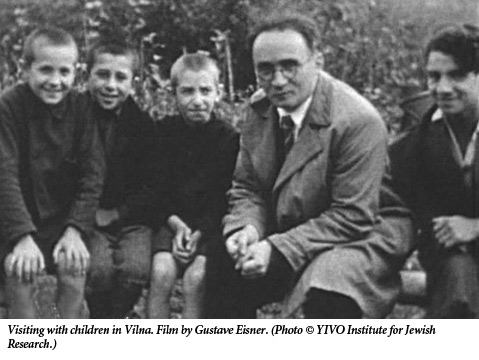

“16mm” purposely does not refer to the probable fate of the subjects of these films in the coming war. It concentrates instead on the happiness of the moment when they met up again with their American kinsman, and waved at his camera so they would be remembered to those they loved.

Suggested Reading

Give Ear O Ye Heavens

Benjamin Harshav’s lifelong engagement in the forms of poetry has been a unique—and uniquely valuable—project.

Building a Sukkah and the Call to Transcendence

David Starr says that Gordis asked the right question, but the answer may be harder than he thinks.

Discrimination and Identity in London: The Jewish Free School Case

How Britain's highest court misunderstands Judaism.

Complicated Community: A Conversation with a Jewish Chavista

What happens to a Jewish supporter of Hugo Chavez when the revolution descends into chaos?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In