The Life of the Flying Aperçu

When I was a graduate student in English at Columbia in the early 1970s, my advisor was Steven Marcus, a marvelous teacher, a renowned authority on Dickens’ fiction and Victorian pornography, and an editor at Partisan Review. He was a protégé of Lionel Trilling, and like Trilling, he was a New York kid who had attended Columbia as an undergraduate and emerged many years later with an indefinable British accent. During the summer following my first year in graduate school, I was hit by a car while I was hitchhiking in the Bronx trying to make my way to New England. I showed up late for the fall semester hobbling on crutches. When I told Marcus what happened, he said, “I spent 18 years of my life trying to get out of the Bronx!”

Columbia, where I was also an undergraduate, oversaw the happy acculturation of young men—there were as yet no women—from all ethnic groups during the post-war generations. There was still a speech test when I was there that was aimed at smoothing out uncouth accents, but the main agent of transformation was the famous Core Curriculum, which required students during their first two years to read the great books of the classical and European tradition. The courses were small and taught by non-specialists, and the texts read in translation. The approach was thematic rather than scholarly or historical. The classroom crackled with ideas, and when students wrote their papers they were expected to confront the text head-on without relying on secondary articles or hiding behind footnotes. The college encouraged a culture of confident brilliance that set it far apart from Columbia’s graduate school, which had been modeled on German universities and had the requisite desiccation and alienation to show for it.

This heady setting is evoked in an absorbing and generous manner in Morris Dickstein’s new memoir of his “sentimental education” (the book ends in his 30th year). Dickstein is a distinguished literary critic and the author of such essential works of cultural criticism as Gates of Eden: American Culture in the Sixties and Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression. What makes his book stand out from an increasingly cluttered field of academic memoirs is the substance of the Jewish identity he brought with him to the Columbia campus.

Dickstein’s parents were not far removed from their Orthodox European origins when they raised Morris and his sister on the Lower East Side before moving to Queens. The move took place for reasons of economic survival, but the family remained loyal to Jewish observance, and their son took several subways and buses each day to continue attending the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School, a yeshiva on the Lower East Side whose curriculum relied heavily on Talmud taught in Yiddish. Dickstein remained there throughout high school, although he became increasingly disaffected from Talmud study. At Columbia he looked for connections beyond the Judaism of his parents and found them in courses in modern Hebrew at the Seminary College of JTS and in summers spent as a counselor at Camp Massad, the exemplar of Hebraist Zionism. And no matter how fraught and exciting his studies on campus, every Friday he would take the train back to his parents’ home and serve as the Torah reader for their synagogue on Shabbat morning.

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role. Nor is it a tale of the sloughing off of family and ethnic ties; the college student remained genuinely attached to his immediate family and the extended clan of his mother’s sisters and their summer gatherings at a working-class town on the northern shore of Long Island. Rather, like his week bifurcated between Morningside Heights and Queens, he sustained a compartmentalized life. Yet while the claims of family remained constant, Dickstein’s mind was being increasingly exposed to the Western tradition, high modernism, and the avant-garde, and we wonder how long he could have sustained the tension.

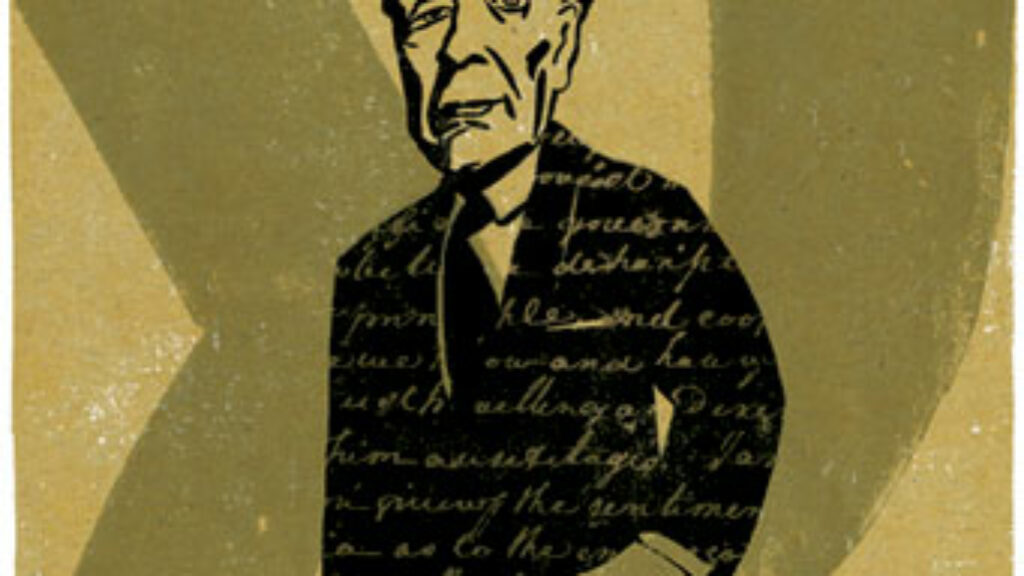

With regard to Dickstein’s undergraduate years at Columbia, the looming figure of Lionel Trilling stands out. Trilling was too ambivalent and skeptical to be a brilliant teacher, but the moral intelligence conveyed by the essays in The Liberal Imagination made a strong impression on Dickstein. The book

. . . offered a model for criticism in a subtle, personal voice that was neither ponderous nor academic but was itself a form of literature. Trilling’s seductive conversational style gave me the impression—or was it a carefully crafted illusion?—of a mind in motion, a man actually thinking things through as he weighed the alternatives and probed the issues before him. It was not the irreverent voice of the coming era but the ambivalent, ruminative voice of the more reflective decade that had just passed, a genuinely engaging voice. Despite its Anglo manner, polite and reserved, it was also a Jewish voice, rarely assertive, honeycombed with ambivalence. It conveyed a sense of the tragic; it spoke not of revolutionary change but of “moral realism.”

As an ex-yeshiva student, Dickstein identified something familiar, even talmudic, in Trilling’s careful consideration of opposing positions staged as an inner conversation. It’s unlikely that Trilling himself ever thought that his manner of thinking derived from Jewish sources or Jewish experiences, but for Dickstein Trilling’s Jewishness, as slight as it was, created a special place in which to stand within the Gentile culture of the English Department. In confronting the cultural turmoil of the sixties and seventies, Dickstein would find himself fortified by what he had absorbed from Trilling: using the tools of reason to adjudicate the claims of unreason.

Trilling figured in yet another way. When, as a college junior, Dickstein picked up a copy of Partisan Review for the first time, he discovered that some of Columbia’s faculty, like Trilling and Marcus, “led a busy and contentious life outside the classroom.” That life, as lived in Partisan Review, Commentary, Dissent, and other elite intellectual magazines of the time, was conducted under rules different from the pedantry and presumed objectivity of academic articles. “For academic work in those days—how times have changed!—you donned the mask of impersonality; for magazine writing you put on the trappings of personality, the opinionated tone of a living person actually thinking, speaking, braving discriminations.” Dickstein soon started a literary supplement to the Spectator, the campus newspaper, which gave him a chance to experiment with boldly speculative writing and “the flying aperçu.” It gave him a chance as well to look beyond the canonized texts read in class and to react to avant-garde theater and cinema taking place downtown. Only a few years later he himself became a contributor to Partisan Review—and then to Commentary newly under the editorship of Norman Podhoretz, another Trilling-influenced Columbia undergrad—and thus began what would become a career-long “double life” as a scholar and a critical essayist.

Graduate school at Yale in the early 1960s was a rude awakening to the realities of the professional study of English. There were fewer Jews and even less Jewish sensibility, though he was mentored by a young Harold Bloom, whom he describes as “the definition of a luftmensch, eloquently aloft in a cloud of his own knowing.” With continental literary theory still just massing on the horizon, the study of English literature at Yale was strung between traditional scholarship and the delicate textual procedures of the New Criticism. After the crackle of the Columbia classroom and the trafficking in big ideas, Dickstein felt constrained and isolated in New Haven. He coped with his alienation by establishing connections outside the inward-looking academic colony. He began a love affair with a young woman he would eventually marry; he began writing for Partisan Review; and, following in Podhoretz’s footsteps, he spent a year at Clare College in Cambridge University, where he studied with the great critic F. R. Leavis. When he returned to Yale, he managed to get a dissertation on Keats written in time to be offered the best job imaginable: returning to Columbia College to teach English.

Yet in the midst of all this energetic good fortune, Dickstein suffered from a variety of unexplained physical symptoms. He experienced sudden panic attacks that laid him low, and he was subject to prolonged bouts of intestinal discomfort. The ailments followed him abroad and then back home, and no amount of medication and therapy made much of a difference. In an oddly related way, he dragged something else around with him during these years: his persistent observance of kashrut. Anyone who spent time in England before the advent of vegetarian cooking knows how truly exasperating it was to navigate one’s way in a society that seemed to conspire to add lard to every foodstuff imaginable, including ice cream. Dickstein adhered to kashrut even as his intellectual and social world moved further and further away from the religious and ethnic matrix of his parents.

Something had to give. Repatriated to Columbia and married with a baby, Dickstein started five-days-a-week psychoanalysis and began to sort things out. But, in a somewhat frustrating way, Why Not Say What Happened comes to a close before the results of that wisdom can be spelled out. The reader is left to make inferences from the subsequent shape of Dickstein’s career. On the academic side of the ledger, his failure to get tenure at Columbia, as painful as it was, turned out to be a fortunate fall. Landing at Queens College of the City University of New York, and later its Graduate Center, he was able to remain part of the scene of the New York intellectuals and to extricate himself from the constraints of being a scholar of English romanticism. “I was,” he writes, “instinctively drawn to what Lionel Trilling called ‘the bloody crossroads’ where art and politics meet.”

On the Jewish side of the ledger, Dickstein seems to have come to the conviction that the love of his family, and his sense of himself as a Jew, was not dependent on his continued observance of rituals he did not believe in. Perhaps if he had come of age in the academy a decade later when the field of Jewish studies was firmly established, he might have felt the tug to turn his energies in that direction. And, indeed, he has taken the American Jewish writers as part of his professional beat, and as a working intellectual he has continually responded to developments in Israeli literature, especially in the pages of The Times Literary Supplement. His main intellectual energies, however, have been aimed at understanding American culture, especially the Great Depression that shaped his parents’ world and the turbulent 1960s that shaped his own.

Suggested Reading

Borges, the Jew

Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentinian Nobel Prize-winning writer was captivated by Judaism. In 1934, he lamented, "hope is dimming that I will ever be able to discover my link to the Table of the Breads and the Sea of Bronze; to Heine, Gleizer, and the ten Sephiroth; to Ecclesiastes and Chaplin."

Exogamy Explored

Naomi Shaefer Riley brings new data and her own personal experience to the issue of intermarriage.

Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

A Hasidic-owned, bicycle-powered tefillin factory in Krakow, Poland.

Lamed-Vovnik

André Schwarz-Bart's posthumous The Morning Star goes where no Holocaust novel has gone before.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In