Exogamy Explored

In recent years boundaries between American ethnic and religious groups have shifted and blurred. White Anglo-Saxon Protestants have officially slipped into minority status. While economic stratification remains quite real, religion and, to a large extent, ethnicity have declined as the bases for social division. Friendships and marriages across religious lines have multiplied, and culture-wide norms of endogamous marriage have passed a tipping point: Pew research data show that one-third of new marriages in the United States bring together spouses from two different religious groups. Two National Jewish Population Surveys (NJPS 1990 and NJPS 2000-01) underlined this trend for the Jewish community: Jewish intermarriage rates were somewhere between forty-three percent and fifty percent. (In the 1950s, about only seven percent of American Jewish households had included one Jewish and one non-Jewish spouse.) As The New York Times columnist David Brooks recently commented, America has become “a nation of mutts, a nation with hundreds of fluid ethnicities from around the world, intermarrying and intermingling.”

Naomi Schaefer Riley grew up in a moderately affiliated Jewish household and is married to an African American man from a Jehovah’s Witness background who has not converted to Judaism. They are happy in their marriage and in agreement on raising their children as Jews (an agreement, she reports, that she stipulated on the first date), but Schaefer Riley has not written an “I’m OK, you’re OK” celebration of interfaith marriage. In ’Til Faith Do Us Part: How Interfaith Marriage Is Transforming America, Schaefer Riley surveys Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and others married to spouses from divergent cultural backgrounds. She finds that couples sharing specific values—including religious values—report higher levels of happiness and marital satisfaction, as well as more resilient marital relationships. Intermarriages “bring less satisfaction to spouses” and “result in a higher likelihood of divorce.” Working from an Interfaith Marriage Survey that she commissioned and also from interviews “with close to two hundred members of the clergy, marriage counselors, and interfaith couples,” as well as a review of recent research on marriage across religious and cultural lines, Schaefer Riley details the manifold ways in which religious difference stimulates conflict in interfaith families. Throughout the book, she criticizes efforts to resolve such conflict through religious homogenization or syncretism, favoring instead the meaningful practice and dynamic transmission of distinctive religious traditions, and her analysis and policy recommendations are keyed to that preference.

In an effort to account for the rising number of “interfaith couples headed to the altar” these days, Schaefer Riley cites the words of David Slagle, an evangelical pastor in Atlanta: “Young people today are intentional about their education, their career, thinking through the possibilities for an occupation and where they want to live and buying a home.” However, when it comes to profoundly important personal choices—mindfully choosing one’s life partner, spouse, and parent of one’s children—“our romantic view of marriage precludes intentionality.” Fuzzy romantic ideas that obscure the very real tensions of interfaith marriage, she charges, are also at fault in the lack of realism that many couples bring to their relationships.

Life cycle changes bring with them new sensitivities to religious differences. Using a variety of suggestive interviews along with some statistical data, Schaefer Riley reveals how differences in religious training often trigger unexpected but powerful resistance to the presence of different religious narratives and rituals in the home, especially but not only where children are involved. Spouses are often surprised to discover that they care more about the rites for newborn naming ceremonies and the religious upbringing of their children than they might have imagined. Religious coming-of-age celebrations loom as children approach middle school. The death of a parent arouses not only grief but also guilt and the desire to seek out familiar religious consolations.

Money, Schaefer Riley observes, also “can be a source of great conflict in any marriage,” but it can be an especially touchy subject in intermarriages, particularly those between Jews and Christians. Non-Jewish spouses who have grown up without the custom of church membership dues—and certainly without the custom of paying for tickets in order to worship in church on the holiest days of the year—are “taken aback by the idea” that Jewish synagogues usually demand that congregants pay to pray. Some Jewish religious institutions have reacted to such objections to the high cost of being Jewish by trying to lower the financial boundaries of group membership in order to attract new adherents. However, since contemporary American Judaism does not require tithing and has no central religious financial holdings to create cushions for congregations, the elimination of paid dues or High Holiday tickets is difficult.

In some intermarried households husbands and wives find themselves engaged in a power struggle, in which each is “allowed” by the other to attend religious services in his or her own religious tradition, with one caveat: Neither should “dig their heels in” and become too much attached to a particular religious tradition. Schaefer Riley’s interviews indicated that some husbands and wives seem motivated not only by a kind of rooting for one’s home team, but also by jealousy. Maintaining a balanced but limited devotion to one’s religion is a sign that the marriage is important—more important than religion.

This deep awareness of real religious contradictions tends to make interfaith couples especially uneasy about the resonances of rituals and ceremonies. Schaefer Riley repeatedly describes spouses defining and redefining “uncrossable lines.” Many Jewish spouses report, for instance, that they can tolerate Christmas flowers, stockings, or small trees within the home, but resist, even deeply resent, outdoor Christmas lights or wreaths, which seem to advertise a Christian home to the world. Schaefer Riley is disdainful of those who obliterate or ignore the distinctiveness of religious traditions: “The notion that Hanukkah and Christmas are both ultimately celebrations of light is now common in certain settings, but it requires an extraordinary dilution of both religious occasions—the birth of the savior and a Jewish military victory over religious persecution—in order to arrive at this point.”

Intermarriage may not be good for religious particularism, and it may be associated with high rates of divorce, Schaefer Riley asserts, but it has an upside. It clearly enhances religious tolerance. Interweaving discussions of diverse religious groups and individual experiences with the findings of large national statistical studies, she cites the “Aunt Susan principle” demonstrated in Robert Putnam and David Campbell’s American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, namely that the presence of family members of different faiths liberalizes Americans. Contemporary American society has been profoundly influenced by the fact that it is harder to believe that infidels are going to hell when Aunt Susan is an infidel. Today’s demographics have created a religious ecology in which Americans are more tolerant because they intermarry more, and they intermarry more because they are more tolerant. Is this dilution of religious cultures, both a cause and an effect of increased intermarriage, a virtuous circle?

Turning to a group often perceived as being located somewhat earlier in the process of acculturation, Schaefer Riley asks whether American “Muslims will in fact go through the same process that Catholics and Jews” have experienced and “be subsumed by the melting pot” while retaining particularistic pride. Comparing the trajectory of Muslim acculturation to that of Jews, she suggests that relaxed Muslims who marry out of the faith will grow more assimilated and less attached with every successive generation, while a fervent Muslim minority will “grow in prominence” within the highly identified community, determining “the future of Muslim institutions from mosques to religious schools.” This analysis will no doubt remind many readers of the 2011 study of the Jewish population of New York, which reflected a similar polarization.

’Til Faith Do Us Part also includes illuminating discussions of individuals and couples who don’t match stereotypical perceptions of interfaith couples, including Druze, Mennonite, and Roma individuals. Schaefer Riley’s interviews bring the ritual non-exclusivity of Eastern religions into vivid light:

Daha, a Sikh, and his wife, Haimi, a Hindu, also believe strongly that their children should be exposed not only to each other’s holidays but also to those of other faiths. Haimi recalls that when she was growing up, her parents would put up a Christmas tree. “We do that for our children. We don’t ever want our children to feel isolated. Those are great holidays. Why wouldn’t we want to celebrate them? We have no problem. If it’s a holiday, we’ll celebrate it.” Daha and Haimi also typically celebrate their respective holidays with their families. Indeed, they have asked both sets of grandparents to take an active role in raising kids religiously. The religious leaders in their faiths do not generally see any incompatibility between celebrating both Sikh and Hindu traditions.

Schaefer Riley compares this pan-cultural approach with the typical exclusivity of the three Western monotheistic religions, “For the Abrahamic faiths, bringing up children in more than one tradition means you must get beyond the traditional meaning of the holidays or at least gloss over how the meanings of the holidays may contradict each other.”

Individuals who marry outside of their own ethnic and religious groups tend to marry substantially later than those who marry endogamously, a subject that Schaefer Riley—never shy about uncomfortable subject matter—enthusiastically takes on. In her penultimate chapter, “Jews, Mormons, and the Future of Interfaith Marriage,” Schaefer Riley asserts that Jews are the American ethno-religious group most likely to marry across religious cultural lines and Mormons the least likely. One Mormon habit Schaefer Riley urges Jews to adopt is earlier marriage and childbearing, which would raise Jewish fertility levels from their current low point, well under replacement level.

Schaefer Riley cherishes the American freedoms and social openness that allow Jews and others to make free personal choices, but she warns readers about potential problems that are implicit in those free choices, implying that if Jews want less intermarriage—or if they want more successful marriages no matter who the spouses are—they should support conditions that foster earlier marriage and Jewish in-marriage. She suggests that Jews can learn from the Mormons how to keep their commitment to their own particularistic values and behaviors strong, while at the same time minimizing entry obstacles. Mormon practice illustrates that “it is actually possible to advocate in-marriage—even denying the possibility of living eternally with one’s family—while at the same time welcoming intermarried couples in the community” and actively encouraging conversion, she says.

This comparison is intriguing but naive. Schaefer Riley pays insufficient attention to the important organizational, structural, and ideological differences between Mormons and Jews. For example, the hierarchical Church of Latter-Day Saints is far more centralized economically and as a polity than the highly decentralized Jewish religious groups. In contrast to the liberal and permissive upbringing of the majority of young American Jews, which expresses itself powerfully in romantic choices, young Mormons are strongly disciplined by communal expectations and are urged to give a number of years to missionary activities around the world.

Schaefer Riley makes imaginative use of a broad range of examples, but despite her eclectic incorporation of data on diverse ethnic groups, she seems to have a rather spotty grasp of the important corpus of American local, national, and international Jewish demographic research—even when those data might support, contradict, or shed interesting additional light on her major points. Her neglect of this body of writing leads to some serious misstatements with regard to her Jewish subjects. She asserts, for example, that “almost no demographic factor or childhood practice seems to change the likelihood that a marriage will be an interfaith one.” Numerous studies (most of which she does not cite) however, unequivocally demonstrate that having a Jewish education greatly enhances the probability that one will make Jewish choices. Over and over again, national and local studies have revealed the demographic factors that affect the likelihood of intermarriage: Jewish population density, Jewishness of friendship circles during high school and college, continuation of formal and informal Jewish education from childhood through the teen and college years, familial Jewish ethno-religious activities, and youth groups, camps, and Israel trips. Independently, each of these factors is highly predictive of the likelihood of in-marriage. Together they have an impact that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Schaefer Riley might have focused more on the dramatic differences between men and women in patterns of intermarried Jewish family life. Intermarried Jewish women—like the author herself—most often aim to raise Jewish children. Intermarried Jewish men, in contrast, frequently articulate ambivalent feelings about religion in general and Judaism specifically—and not coincidentally about Jewish women. These men are less likely to transmit Jewish religious culture to the next generation, and their children are much less likely to receive Jewish education or identify as Jews when they reach adulthood. The greater religious identification of American Jewish women and the lesser identification of Jewish men—a gender imbalance that turns historical Jewish patriarchy on its head—is yet another aspect of American acculturation.

In America today, the norm of endogamy has been reversed. Intermarriages may not be “for the faint-hearted,” as Schaefer Riley wryly comments, but they are an irrefutable aspect of American life. Schaefer Riley’s explorations of her complex subjects are framed by two conflicting goals: “fostering a tolerant society,” while at the same time “keeping religion strong” by advocating “the importance of forging marriages around common beliefs and behaviors.” Schaefer Riley values religious distinctiveness and believes that America will be impoverished if it declines. At the same time she celebrates the increase in tolerance that accompanies sectarian dilution. Her arguments often shift back and forth, and she appears to be ambivalent about which of these considerations should take priority. This ambivalence reflects the ultimately irresolvable tension between the goal of perpetuating substantive religious and cultural communities and the American credos of egalitarianism, self-fulfillment, and individual autonomy that Jews and others have gratefully embraced.

Some readers have attacked Schaefer Riley for her politically incorrect emphasis on the fundamental problems that emerge within many interfaith marriages. Other readers—including this one—resonate with her conviction that the individual, family, and community each represent valid concerns. Despite its shortcomings, ’Til Faith Do Us Part is fresh and even-handed, and Schaefer Riley’s countercultural willingness to challenge American Jewish liberal pieties is a decided strength of her important book.

Suggested Reading

“With a Wolf in One Eye”: Sutzkever in Israel

From his birth just outside Vilna in 1913, Abraham Sutzkever led a life that had merged, as though on a God-ordained path, with the fate of the Jewish people in the 20th century. It of course follows that that life would reach its culmination in Israel.

Summer of ’36

By 1936, Joseph Roth’s alcoholism was increasingly desperate, and his friendship with Stefan Zweig was frayed. But still that summer gave them an opportunity to recover something of their old friendship.

Problems with Authority

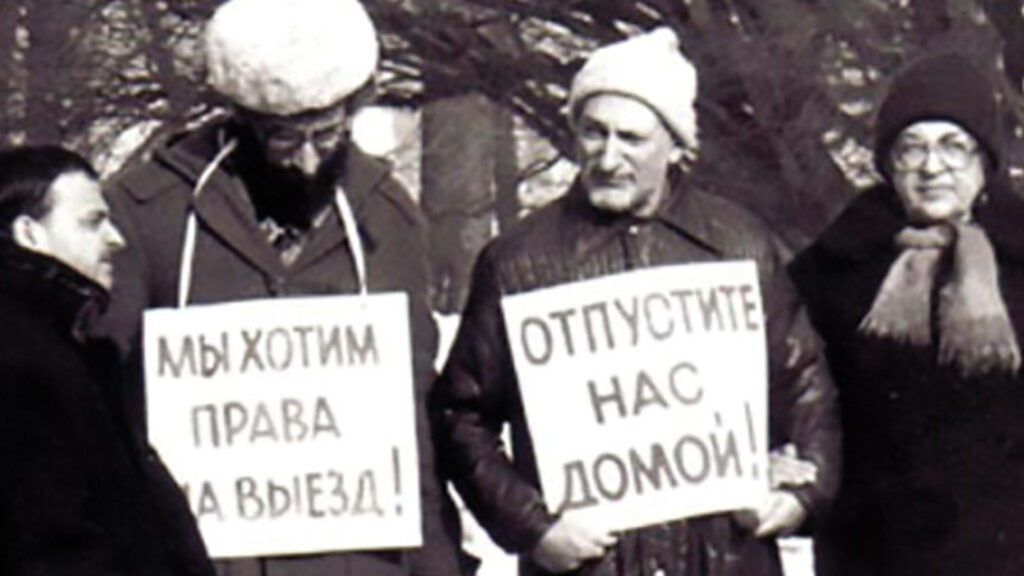

Paul Goldberg’s latest novel, The Dissident, is a narrative tour de force that plays far too fast and loose with the historical facts, leaving its readers deeply misled.

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In