Palestine Portrayed

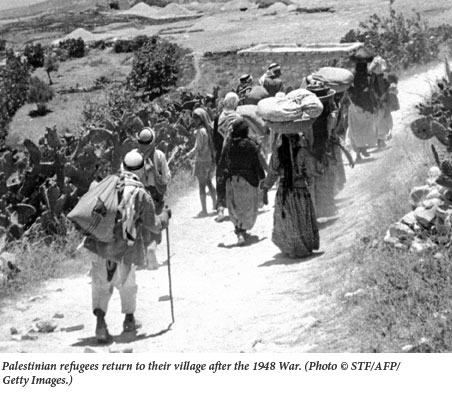

For a long time, the 1948 War was the defining event of the Arab-Israeli conflict. By the time the fighting ended in July 1949, the Jews had consolidated their control of a state with much more expansive borders than those drawn by the United Nations in 1947. The Arabs of Palestine did not fare as well. Instead of acquiring a country of their own alongside Israel, they emerged from the 1948 War stateless, fragmented, and dispersed. Since neither they nor the neighboring Arab states were prepared to accept the permanency of this situation, the Arab-Israeli conflict seemed destined to endure—until the Six-Day War in June of 1967 broke the stalemate. The swiftness and magnitude of Israel’s victory, the extent of the territories captured, the ramifications for the Soviet-American competition in the Middle East, and the blow dealt to Pan-Arab nationalism all combined to overshadow the events of 1948.

Lately, however, the 1948 War and the problems it left unresolved have returned to the top of the agenda for both diplomats and historians. It is in this context that one has to situate Palestine Betrayed, the new book about the events of 1948 by Efraim Karsh, who heads the Middle East and Mediterranean Studies program at King’s College, University of London.

To understand the renewed attention to 1948, we must first reconsider the complex outcome of 1967. With all of mandatory Palestine west of the Jordan River in its hands, Israel could conceivably have worked toward the creation of a Palestinian state along the lines of the one that was supposed to have been established in 1948. But the overall effect of the Six-Day War was to lessen the likelihood of such an eventuality. Many Israelis concluded from the crisis of May-June 1967 that it would be unsafe to return to the narrow prewar borders. A homegrown messianic movement that regarded the retention of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as a sacred duty quickly took shape, generating bitter divisions in Israeli society.

Meanwhile, Palestinian nationalism enjoyed a dramatic resurgence. The leaders of the PLO became full-fledged players in Arab politics; and Jordan, as a consequence, relinquished its claim to the West Bank, which it had held from 1948 to 1967. Israel’s Arab minority (almost 20% of the state’s population) underwent a process of radicalization as a result of its interaction with the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza and with the larger Arab world. As time went on, criticism of Israel’s continuing control of a Palestinian population and its project of settling Jews in the West Bank and Gaza mounted within Israel itself, in the Jewish Diaspora, and in the international community.

After Israel signed peace treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994), negotiated with Syria, and normalized relations with Arab countries in the Persian Gulf and North Africa, it had expected to reduce the scope and intensity of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. As Olivier Roy has pointed out, instead of diminishing it, these diplomatic breakthroughs served only to transform the conflict into an “Israeli-Palestinian one.” Striking evidence of this unanticipated development can be heard in President Barack Obama’s formulation of the issue in his 2009 Cairo speech last year. “The Arab-Israeli conflict,” he declared, “should no longer be used to distract the people of Arab nations from other problems. Instead, it must be a cause for action to help the Palestinian people develop the institutions that will sustain their state, to recognize Israel’s legitimacy, and to choose progress over a self-defeating focus on the past.”

The 1948 War had given birth to two conflicting narratives that dominated the discourse for the following two decades. For the Palestinians and the Arab world in general, 1948 was a nakba, a catastrophe. The term first appeared in 1945 as a warning against the disaster that would result from a Jewish victory in the struggle for Palestine, and gained currency after it was used by the Syrian intellectual Qustantin Zurayq. His book, Ma’na al-Nakbah (The Meaning of Catastrophe), famously castigated the Arab world for the weakness, division, and corruption of the old order that made a Jewish-Israeli victory possible.

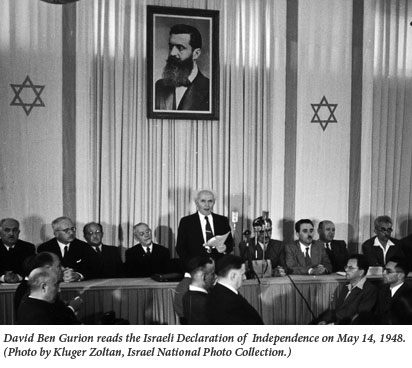

For Israel, the 1948 War was the War of Independence, the culmination of the Jewish people’s quest for statehood and “return to Zion,” and liberation from increasingly hostile British control. The war appeared to have been a miraculous victory of the few against the many, a vindication of the Jewish right to a sovereign, safe haven after the Holocaust, and a morally justified victory over Arab foes who had rejected the UN’s partition resolution, launched a civil war in Palestine, and then invaded the territory of the young Israeli state.

In their effort to boycott, isolate, and de-legitimize Israel, the Arab states made the issue of the Palestinian refugees the cutting edge of their diplomatic offensive. The most basic questions—How many? How was the problem created? Were they expelled by Israel? Did they leave? Were they encouraged to do so by their own leadership or the Arab states?—were the subject of annual debates in the UN, innumerable brochures, and book after book. In response to this propaganda onslaught, the Israeli establishment and mainstream historians dealt very guardedly with the subject. If Israeli historiography of the 1948 War during the 1950s and 1960s was largely subordinated to political concerns, Arab and Palestinian historiography of the war was quite scant.

Far more significant was the appearance of a revisionist Israeli school that set out to challenge the standard Israeli version of what happened in 1948. The first signals of change were the publication of Tom Segev’s The First Israelis in 1984 and Simha Flapan’s The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities in 1987. Segev, a journalist and popular historian, depicted the seamy side of Israel’s early history and sought, among other things, to cast doubt on the new state’s readiness to make peace with all of its neighbors. Flapan was a political activist, a member of the left-wing Mapam party and affiliated with the journal New Outlook who set out to destroy what he regarded as the seven Israeli myths about 1948: the Zionists accepted the UN partition and planned for peace; the Arabs rejected the partition and launched war; the Palestinians fled voluntarily, intending re-conquest; all of the Arab states united to expel the Jews from Palestine; the Arab invasion made war inevitable; defenseless Israel faced destruction by the Arab Goliath; Israel has always sought peace, but no Arab leader has responded.

Flapan was not a scholar and his book was full of flawed arguments and historical errors, but it was not long before three academics, Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, and Avi Shlaim, came out with books and essays that tried to inject academic substance into Flapan’s arguments. The three soon became known as Israel’s “new historians.” In an article published in the magazine Tikkun, Benny Morris explained the rationale and purpose of the group’s mission and the special emphasis put on the 1948 War:

Inevitably, the new historians focused their attention, at least initially, on 1948 because the documents were available and because that was the central, natal, revolutionary event in Israeli history. How one perceives 1948 bears heavily on how one perceives the whole Zionist-Israeli experience. If Israel, the haven of a much-persecuted people, was born pure and innocent, then it was worthy of the grace, material assistance and political support showered upon it by the West over the past forty years—and worthy of more of the same in years to come. If, on the other hand, Israel was born tarnished, besmirched by original sin, then it was no more deserving of that grace and assistance than were its neighbors.

The new historians did indeed benefit from the opening of Israeli, American, and European archives. But they also wrote in the shadow of the controversial war on Lebanon in 1982 and the first Intifada, which began in 1987. Contemporary political debates and agendas echo throughout their works. Morris’ The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem had the greatest and most long-lasting impact, for he dealt a heavy blow to the Israeli argument that the Palestinian refugees had “left” and not—except in a few minor cases—been expelled. The carefulness of his research and his measured academic tone distracted many readers and critics from his political agenda (implicit in the book and trumpeted in the Tikkun article) and his failure to put the book’s topic and findings into context. Morris left unmentioned the expulsion of most of the Jewish population from Arab countries and neglected to note that the other, much larger post-World War II refugee problems in Europe and the Indian subcontinent had long ago been resolved.

The offensive of the new historians met with a counter-offensive, led by David Ben Gurion’s biographer Shabtai Teveth and Efraim Karsh, the title of whose first book on the subject, Fabricating Israeli History, speaks for itself. Teveth, Karsh, and others accused the new historians of deliberately misrepresenting evidence, doing sloppy archival work, and politicizing history. Karsh’s attack on the new historians was particularly harsh, and was met, especially by Morris, with a strident response. Indeed, the debate at times seemed to have become a personal feud between Karsh and Morris.

As the controversy generated by the new historians subsided in the 1990s, its impact continued to be felt in two principal ways. It inspired the work of several Palestinian intellectuals who were clearly embarrassed by the fact that the nakba was being revisited and given new prominence by Israeli, rather than Palestinian, historians. More significantly, it prompted less ideological Israeli scholars to take a fresh, more skeptical look at the traditional historiography of 1948. This group included scholars such as Mordechai Bar-On (a former IDF senior officer, and a left-wing critic of Israel’s post- but not pre-1967 policies), Yoav Gelber (a University of Haifa historian), and—of all people—Benny Morris. Yasir Arafat’s conduct at the Camp David summit of July 2000 changed Morris’ mind. His recent book, 1948, diverges from his earlier work in several ways, most importantly by putting the war’s (and the controversy’s) major issues in their larger historical context.

Benny Morris’ former colleagues, however, remain unrepentant. Avi Shlaim has modified some of his views, but on the whole has continued to publish in the same anti-Israel vein. Ilan Pappé has gone further afield. He has left Israel to teach in Britain and published a book with the disgraceful title of The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. If Morris in his original incarnation failed to put the issue of the Palestinian refugees in historical context, Pappé gives it a fictional one. Not only, in his opinion, were expulsion and premeditated population transfer inherent in Zionist thought, but the founders of Israel actually put into practice Bosnia-like ethnic cleansing, including real atrocities. To support these unwarranted conclusions, Pappé makes cavalier use of the evidence at his disposal. A particularly egregious example of his methods is Pappé’s description of a secret meeting in the “Red House” building in Tel Aviv on March 10, 1948, when Ben Gurion and his cabal (“The Consultancy”) supposedly “put the final touches to a plan for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine.” Pappé leaves to the reader’s imagination what his text hints at but does not make explicit: the comparison to the Nazi conference at Wannsee.

It is against this backdrop that Efraim Karsh sets out to demolish the whole edifice of nakba literature. Unsatisfied with the balanced accounts of Gelber and the new Morris, Karsh has invested several years in archival research in order to come up with a radical, counter-revisionist reading of the 1948 war. He argues that the Palestinian people and their cause in the years 1920-1948 were betrayed not by Britain or by the Zionist movement but by their own leaders and by the Arab states.

The vast majority of the Palestinians, Karsh reports, were not opposed to the Zionist enterprise. There were even times during the Mandate years when it would have been possible to lay the groundwork for peaceful and harmonious relations between Jews and Arabs. In late 1939, for instance, after the flight of the Mufti of Jerusalem to Nazi Berlin, and the suppression of the revolt he had instigated, “ordinary Palestinians sought to return to normalcy and reestablish coexistence with their Jewish neighbors.” Jewish and Arab citrus-growers and planters collaborated on economic plans. “In April 1940, the first ever Jewish-Arab hockey match was held in Jaffa, to the cheers of a big crowd of Arab spectators.” At the same time, “Jews rented accommodations in Arab villages and opened restaurants and stores with the villagers’ consent.” Even some “former rebel commanders and fighters made their peace with their Jewish neighbors.” Unfortunately, however, this amicable spirit found no political support on the Arab side.

After World War II, the Mufti and his allies succeeded in reasserting their control over the Palestinians. They repeatedly spurned any notion of compromise with the Zionists and called for their destruction. Together with the leaders of the Arab states, who had their own designs on Palestine, they rejected the UN partition resolution and went on the warpath. In the course of the subsequent fighting, the Palestinian Arab community collapsed. According to Karsh, most Arabs left Jewish-controlled territory of their own volition, although there were also some instances of expulsion.

Karsh further argues that in the immediate aftermath of the 1948 War the Palestinians did not perceive their calamity as a “systematic dispossession of Arabs by Jews.” They understood that the blame lay with their own leadership. “It was only from the early 1950s onward,” he writes, “as the Palestinians and their Western supporters gradually rewrote their national narrative, that Israel, rather than the Arab states, became the Nakba’s main, if not sole, culprit.”

Much of what Karsh says is true and needs to be said. The Palestinian leadership, headed by the Mufti, committed a long series of moral and political blunders. Had it responded positively to British efforts to construct political institutions in Mandatory Palestine when the Palestinian Arabs constituted a large majority of the population, the course of history would have been different. Had it accepted the partition resolution, a Palestinian state would probably have been established. The Arab states and their leadership likewise committed a long series of mistakes and misdeeds, as the Palestinians themselves knew better than anyone else. And it is also true that many Palestinians were willing to cooperate and collaborate with the Yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine) and were dragged into a disastrous conflict by their leadership.

But all of this and more does not negate the significance of Israel’s own role as the other protagonist in a classic national conflict. The Zionists’ entrance into Ottoman Palestine in order to build their own state inevitably brought them into conflict with another national movement, to whose emergence they themselves made a major contribution. If the early Zionists originally believed that they were “a people without a land” coming to “a land without a people,” they discovered soon enough that this was not the case. Ever since the publication in 1907 of Yitzhak Epstein’s “A Hidden Question,” Zionism’s leaders and ideologues have had to grapple with what came to be known as “The Arab Question.” This essential dimension of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is obscured by Karsh’s emphatic and exclusive insistence on the “betrayal of Palestine” by Palestinian and Arab leaders in the events leading up to 1948.

Karsh similarly oversimplifies matters when he turns to the years after 1948 and especially to the contemporary political situation. Drawing a straight line from the Mufti to Arafat and Abu Mazen, he accuses the latter two of obstructionism and thus with responsibility for the perpetuation of the conflict and the plight of the Palestinians. He is right about Arafat; but Abu Mazen has yet to be fully tested and Salam Fayyad may well represent a new phenomenon. Yet here, too, one should remember that Israel is the other actor in the unfolding drama, and that in Israel there is a powerful political camp that is fiercely opposed to a solution based on compromise with the Palestinians.

Benedetto Croce’s dictum that “all history is contemporary history” rings particularly true with regard to the 1948 War. The events and consequences of that war continue to shape Arab-Israeli relations and the war’s historiography is a political battlefield. Efraim Karsh is a veteran of this academic combat. In Palestine Betrayed he has re-entered the trenches, his arsenal replenished with archival data. His agenda is clear: to go beyond (the new) Morris and Gelber and to destroy the entire edifice of the nakba literature. What Karsh has failed to realize is that in the battle of ideas, the surgeon’s scalpel is often more efficient than the demolition squad’s sledgehammer.

Karsh may not be a delicate historian but his book has significance beyond the genuine archival work he has done. The Middle East sections of campus bookstores and libraries are full of the works of irresponsible critics of Israel such as Pappé, whose flawed arguments and outright falsehoods slip all too quickly into the media and onto the web. A twenty-second internet search yields such gems as an op-ed piece by an English professor named William Cook, entitled “Born to Deception.” According to Cook, “[w]hat should be obvious by now, after the carefully researched and scholarly work of Ilan Pappé in his Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine and the equally well researched work of Benny Morris in his Righteous Victims . . . is the truth about the creation of the state of Israel.” The appearance of Palestine Betrayed on bookstore shelves will make it easier for inquisitive readers and web-surfers to see for themselves that the truth about the founding of Israel is not as simple as some of its professional and amateur critics would like to make it.

Suggested Reading

It Was Like This: Excerpts from an Academic Memoir

Scenes from Anita Shapira’s gripping memoir.

A Tale of Two Synagogues

Frank Lloyd Wright built a dazzling temple outside Philadelphia. Too bad he didn’t look closely at the synagogue of Gwoździec, Poland, built two hundred years earlier.

Spinoza in Shtreimels: An Underground Seminar

A professor and three Hasidim walk into a bar—to study philosophy. True story.

Perish the Thought

Bruno Chaouat dares to ask whether, given the moral autism of so many of Theory’s luminaries when facing the basic political questions of our time, his own romance with it has been a similar waste.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In