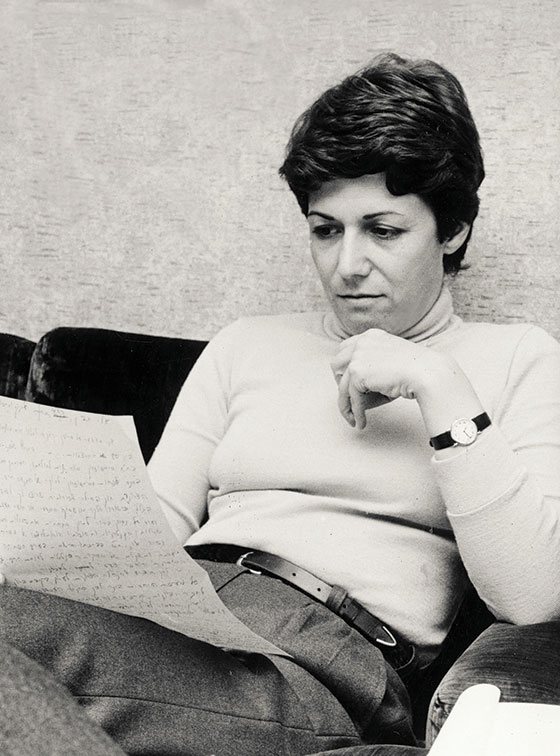

It Was Like This: Excerpts from an Academic Memoir

As a graduate student at Tel Aviv University in the late 1960s, Anita Shapira was entranced by the modern European historian Shlomo Na’aman’s seminar on Karl Marx and the Revolution of 1848. But her responsibilities as a young mother made it impossible for her to leave Israel to conduct related research, and the only thing that Na’aman could suggest to her was to work on the British Chartists, whose newspaper was accessible, in microfilm, at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. The thought of doing that left Shapira cold, but as she was leaving Na’aman’s office, she was suddenly struck with an idea: “Maybe we can apply what we learned in the seminar to Eretz Yisrael?” Na’aman agreed, and thus, as Shapira reports in her newly published memoir, Kacha Zeh Haya (It Was Like This), “almost by accident and without any prior knowledge,” she became a historian of Israel.

Much larger strokes of luck had landed her in Israel in the first place. She was lucky to be smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto as a toddler and to survive the war in a convent, and lucky to be adopted by a Jewish couple that chose, for uncertain reasons, to head for Palestine in the summer of 1947. But that was only the beginning of her good fortune. “How many Jewish babies born in Warsaw in 1940,” she asks, enjoyed a warm family life like the one she has had? She was likewise lucky to be able to “wake up every morning and pursue my hobby as a profession, to write books, to bring up generations of students, to shape a new generation in Israel studies.”

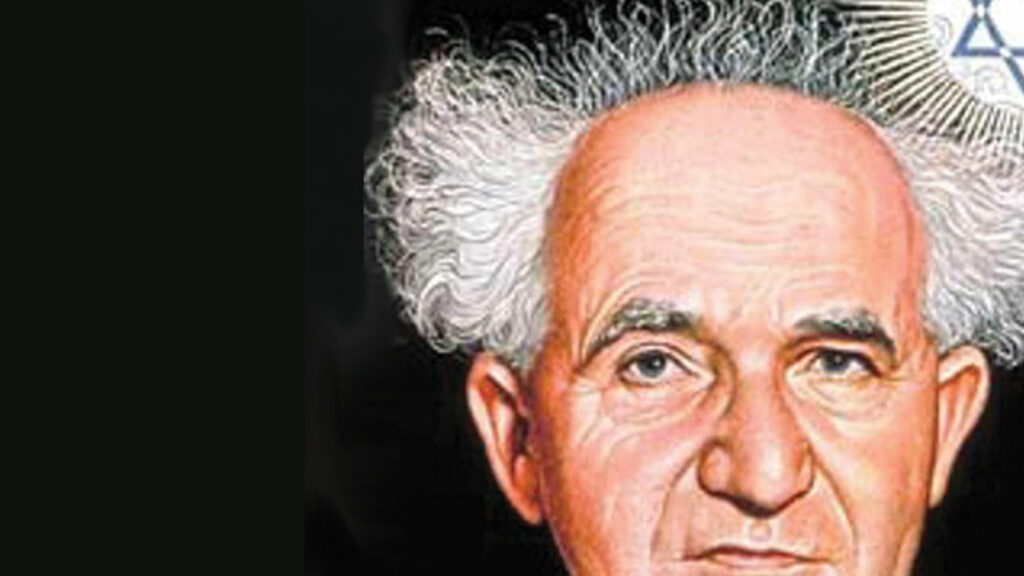

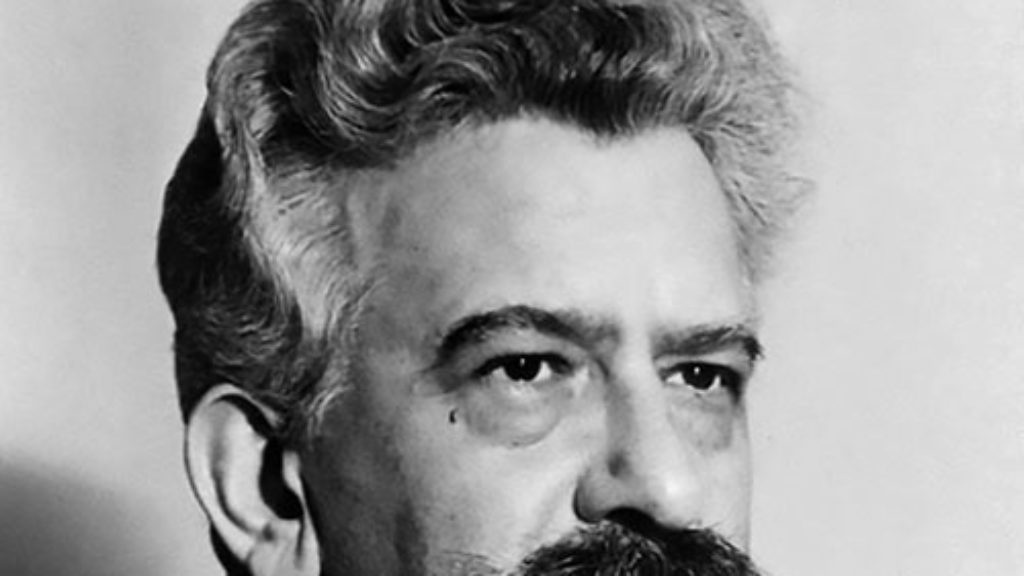

Although there are no current plans to translate Kacha Zeh Haya, most of Shapira’s historical work is available in English, including her landmark biographies of Berl Katznelson, a leading figure in the Zionist Labor movement, the novelist Yosef Haim Brenner, General Yigal Allon, and David Ben-Gurion, along with Land and Power: The Zionist Resort to Force, 1881–1948 and Israel: A History. Her memoir intertwines the story of writing these major works with that of her life, not to speak of the (academic) war stories. Below are three short excerpts that will give the English reader a flavor of Shapira’s latest book—and life.

1942

What is a two-and-a-half-year-old girl capable of remembering? She didn’t remember many things. Only a few images were etched in her memory. Her first recollection was of grandma washing her in a small wooden tub set on a table, under the light of a bare electric bulb. Was this really her grandmother or perhaps a neighbor? There’s no one to ask. Her second memory was of crossing over the wall of the ghetto: night. She is in the arms of her mother, Felicia. A wall of red bricks, and on top of them shards of glass and a strip of barbed wire. On the other side of the wall a scary person is pacing, with a flashlight in his hand. She said something and her mother then said to her: “Shhh!” and she fell asleep. When she woke up, it was already morning, and she was in something like a classroom, a wooden booth, and her mother, whose face she cannot remember and who is like a silhouette, is pushing and encouraging her to get close to a woman and to girls who were there. Did she part from her with a kiss? An embrace? She doesn’t remember.

When she herself became the mother of a girl, she would watch her and think: this is what I looked like when my mother parted with me. Would I have been able to part with my daughter? What overpowering despair and what certainty of destruction, what spiritual powers were necessary to do such a thing? This recollection also passed over to the third generation. Her daughter, too, watched her small daughter and thought: what goes on in the head of a girl like this who from one day to the next is cut off from her mother? That was lost from memory.

1984

One fine day Alexander Sand, the editor of the Ha-kibbutz Ha-meuchad Publishing House and an author in his own right, invited me to chat over a cup of coffee. This was about a year or a year and a half after the publication of Berl. As I have noted, the book was received by the Ha-kibbutz Ha-meuchad movement with mixed feelings. And now, Sand suggested to me in the course of our conversation that I write a biography of Yigal Allon. I didn’t know Allon personally. I knew of course who and what he was, but I never exchanged a word with him. A short time before Berl came out, I was at a screening of Haim Guri’s The Last Sea. The audience included many Palmach veterans. I saw the adoration that flowed from them toward Allon, who came to the screening to honor Guri, but since these were still “pre-Berl” days, none of my acquaintances at the event saw any reason to introduce me to him. A short time after that, Allon died from a heart attack. Now, the veterans of Ha-kibbutz Ha-meuchad, [Yisrael] Galili at the head of them, sought to draft the new luminary in “the world of biographies” in Israel to write about the man they adored. Thus I acquired the trust and acceptance on the part of just that sociopolitical sector that had seen me as an adversary since the publication of my article on the Labor Brigade.

Was I the right person to write about Allon? Unlike in the case of Berl, I would here have to grapple with an assigned subject, one that I hadn’t come up with myself. Did I accept the proposal simply because I was flattered that they thought it right to choose me, even though I wasn’t “one of them”? No doubt that played a part in my decision, but more than that I was enchanted by the idea of dealing with a son of the land, a sabra, who, unlike Berl and the rest of his generation, came from “there.” This was a new subject, different from the subjects with which I had dealt up to then, and it touched on the core of the sabras, an entire social group that had novels and songs composed about it. Working on it introduced me to a social and cultural milieu different from those that I had previously written about.

I was familiar with the image of Allon and his depictions in the media. I wasn’t charmed by him, but I knew that for his comrades in the Palmach, he was the object of esteem, a leader from whom others had sneakily and querulously stolen the crown that was rightfully his. When Sand saw that I doubted whether there was anything more to the figure of Allon than a handsome and daring youth, he told me about Allon’s daughter with special needs. Sand knew that I was looking for spiritual depth and therefore shared with me a secret that was unknown to the general public to render Allon appealing to me. In the end, this opened me up to him.

1994 and beyond

Of the three hallowed figures in the band of “new historians,” the most respectable was Benny Morris, but he, too, got swept up by the debate into zones that should have been off limits. For example, in a forum that took place at the University of Haifa, he argued that I only knew how to write well. I didn’t respond: what could I say? That there’s substance to what I write, not just a fluent style? Since those disputatious days, I’ve been grateful to Danny Gutwein, who rose in my defense and uttered some choice words. Avi Shlaim was hostile in his writings, and it was possible to see in the writings of this Israeli émigré his enmity toward the state he left behind.

The most revolting was Ilan Pappé. In July 1994 there was a symposium at Tel Aviv University that included Moshe Lissak of the Hebrew University, Shlomo Svirsky (a critical researcher in the social sciences), Pappé from the University of Haifa, and me, at the time dean of the faculty. The Bar Shira Auditorium was full, without an empty seat. There was tension in the air. You could cut the heavy air in the room with a knife.

The debate was mainly between Pappé and me. At a certain point, when he made the argument that the Haganah’s Plan D included a sweeping order for the expulsion of all the Arabs, an argument voiced by certain Arab researchers, I lost my composure and replied that he was lying. From the audience, of which a significant portion were members of Naki (the Communist youth movement) who had been drafted to participate in the event, there arose an angry cry. The dramatic but baseless comments of Aharon Meged, who took to the floor and spoke in defense of the generation of 1948, hurt more than they helped. Pappé tore him to pieces. I swore then and there never to appear again on the same stage as Pappé: it’s possible not to agree about interpretations, but the moment one begins to invent facts and to present them as truth, there’s no common ground on which a discussion can take place.

In retrospect, there’s no doubt that the debate with the post-Zionists gave greater exposure to the historiography of Zionism and injected it with renewed energy. The confrontation motivated many young people to take interest in the subject and brought about greater openness to innovative historiographical approaches.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Indispensable Man

In his effort to cut David Ben-Gurion down to size, Tom Segev blames him for failures that were not his and gives him insufficient credit for his achievements. A closer examination of the historical record reveals a greater man than the one Segev attempts to dissect.

Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

When the editors at Jewish Life asked the venerable civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois to speak about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, they had no idea that it would lead to a priestly blessing.

In and Out of Time

A new collection of Heschel's writings plucked from obscurity and presented with clarity to English readers adds to our understanding of the centrality of time in Heschel’s worldview.

Adventure Story

Anita Shapira's new book raises the bar for short histories of Israel.

Pedro Bilar

Anita Shapira does not mince words, and I truly commend her for that. Every nation has its Quislings, its Petains, and even its sadistic Kapos. Unfortunately, Israel seems to be no different, at least as far as self-hating academics are concerned.

Having read the excerpt, I will look out for her book, also if only be available in Hebrew.

May I respectfully point out one mistake in this article, namely in the caption of BG, Allon, and Rabin's picture? May 25, 1967 was not during but before the Six-Day War...