Spy vs. Spy

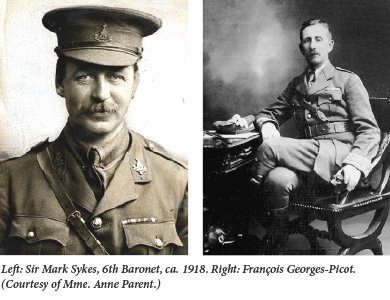

In the middle of World War I, Mark Sykes, François Georges-Picot, and a few other British and French statesmen secretly divided up responsibility for the vast Middle Eastern territories then in the possession of the Ottoman Empire. This agreement marked not just a milestone in Franco-British imperial competition but the beginning of what James Barr describes in A Line in the Sand as a veritable cold war.

British control of Palestine had its origins in the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, which provided for power-sharing with the French. It wasn’t long, however, before the British managed to exclude their wartime allies from any official role in the Holy Land. Even before the Palestine Mandate was fully in place, however, the British suspected the French of trying to destabilize it. During the Arab riots of 1920, W.F. Stirling, the governor of Jaffa, was “convinced that the trouble he had to deal with ‘was invariably instigated by the French Consulate.'” The French, for their part, believed that the British helped to subsidize the ferocious Druze rebellion that they faced in Syria in 1925–1926. In fact, the French and British overestimated each other, if not the measure of schadenfreude that each experienced upon witnessing the other’s difficulties.

Great Britain scored a victory over France in 1931 when it insured that a pipeline extending from the rich oilfields of Iraq to the Mediterranean would terminate not in French-controlled Syria but in Haifa. But France soon had its revenge, when it permitted the sinister mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, and other rebels against British authority to take shelter in Lebanon following the renewed outbreak of fighting in Palestine in 1937. When the British demanded their arrest, the French shrugged their shoulders. A new treaty with Syria limited their ability to help, they said, even though the treaty had not been ratified by the French parliament and never would be. Britain, or more precisely Gilbert MacKereth, the consul in Damascus, responded by launching a covert counter-terror campaign on Syrian soil that included bribery, spies, and hit men.

British counter-terror efforts in Palestine itself—including border fences, cordon and search operations, and house demolitions—were fairly unsuccessful until a “young, well-connected, and faintly unhinged army officer,” Orde Wingate, entered the fray. His Special Night Squads taught Haganah members, including Moshe Dayan, how to prevail over “primitive and ignorant” Arab fighters who were, he explained, “especially liable to panic” after the sun went down. Together with overwhelming conventional forces, they quashed the Arab uprising in 1939, but they could not change the larger geopolitical situation.

The approaching world war required Britain and France to repair their relations. Gilbert MacKereth was even obliged to cease his secret payments to the Syrian prime minister. The British situation worsened when the swift fall of France put the Vichy regime on the borders of Palestine. Assurances from the Vichy leaders in Syria that they would not attack the British quickly proved false as German forces landed there to assist the Nazi-backed coup in Iraq in April 1941. To shore up their own position, the Free French promised independence to the Syrians in exchange for their support. The British then countered with a statement of support for Arab independence in Syria and Lebanon, which they backed up with secret financial aid to the Druze and Bedouin.

Then, in July 1941, British and Free French forces invaded Syria from two directions and conquered it in a campaign that was not without its amusing moments. Roald Dahl, later to become known as the author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (and something of an anti-Semite), remembered a bombing raid on a Vichy airfield, in which he saw out of the window of his plane “a bunch of girls in brightly coloured cotton dresses standing out by the planes with glasses in their hands having drinks with the French pilots.” Showing off their aircraft to their girlfriends was, Dahl wrote, “a very French thing to do in the middle of a war at a front-line aerodrome.” He and his fellow gunners held their fire and watched “the girls all dropping their wine glasses and galloping in their high heels for the door of the nearest building” before destroying five French planes on the ground.

Syria and Lebanon continued to simmer throughout the remainder of the war. For lack of a better alternative, de Gaulle was compelled to reappoint hated Vichy administrators, which angered the Arabs. This, in turn, forced the British, who kept troops in the area, to pay off local tribesmen to keep the peace. To complicate matters further, Roosevelt’s Atlantic Charter was anti-imperial and pro-independence. All this intensified British efforts to muscle the French into granting greater freedom to the Arabs under their control. But if the British meddled in Syrian affairs, the French could do the same in Palestine.

Zionist cooperation with the Free French dated back to the fall of 1940, when David Hacohen, the director of the construction company Solel Boneh, allowed Free French activists to set up a secret radio transmitter for Radio “Levant France Libre” in his Haifa home. From there they were able to witness on November 25 the explosion on board the refugee ship Patria that inadvertently resulted in the death of 263 Jews.

“We stood there mouths open,” recalled one of them, Raymond Schmittlein, as Hacohen admitted that the cause of the blast had been a mine that Haganah had smuggled aboard to cripple the vessel so that it could not depart. Hacohen then asked them whether they thought that modern Jews lacked Samson’s courage. “That won us over,” Schmittlein said. “A national determination of that order could not but triumph.”

Once they were established in Lebanon and Syria, the Free French began to support not only the Haganah but also the Irgun and Lehi (better known as the “Stern Gang”) in their terror campaigns against the British. This included arms, money, and safe haven in Lebanon, as well as intelligence gleaned from spies inside the British establishment in Palestine.

Even after their exit from Syria in 1945, the French continued to meddle. By 1947 they were granting tacit permission for Jewish refugees to board ships in France bound for Palestine and indirect support for a Lehi bombing campaign against British targets in London itself, provided this was not done from French soil. Just to make sure, though, “before Princess Elizabeth—the present queen—visited [France] in 1948, the French police met the Irgun face-to-face to double-check that they would not try to kill her.”

When the question of Palestine came before the UN General Assembly in November 1947, France was initially afraid to vote in favor of partition, lest it stir up too much angry nationalism in its North African colonies. Only Bernard Baruch’s arm-twisting brought the French into line. The powerful and influential banker, then serving as the U.S. representative on the UN Atomic Energy Commission, bluntly warned France’s UN ambassador “that if France failed to support partition—a policy that he knew President Truman personally supported—French stock was bound to fall in the United States.” Three days later, France voted in favor of partition, and before long, arms from Czechoslovakia flowed through France to the new state of Israel.

Barr makes excellent use of quotations from archival materials, such as Churchill’s rather overdue advice to his Machiavellian representative in Lebanon, Edward Spears, to “try to keep your Francophobia within reasonable bounds.” However, the book is not without its faults. The Arabs who appear in its pages are mostly villains and pawns in walk-on roles. The portraits of Jews are sympathetic but shallow. Americans, Russians, Germans, and others remain largely invisible. Barr also fails to adequately set the stage by reviewing the 19th-century rivalry for the Levant. Ottoman capitulations, Napoleonic wars, European schools, missionaries, consulates, tourism, archaeology—all are missing from Barr’s account.

Other weaknesses are both narrative and structural. Barr’s detailed accounts of obsessive plots and counterplots are sometimes difficult to follow, and the larger geopolitical contexts are also almost completely absent. Still, even if he does not paint on a broad canvas, Barr does a fine job with the details of a crucial but insufficiently known aspect of Middle Eastern conflict during the first half of the 20th century.

Suggested Reading

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

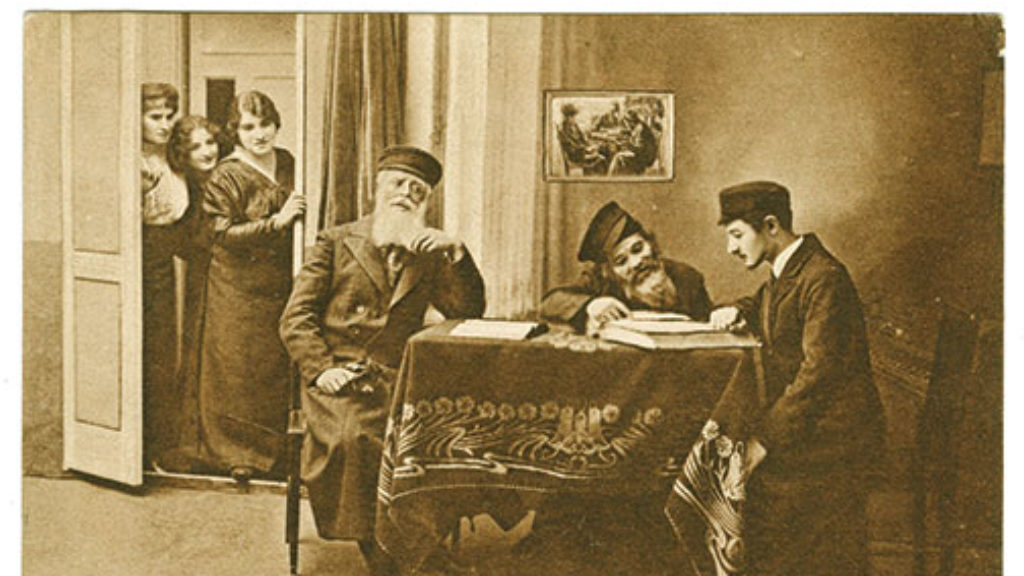

What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

Yiddish Genius in America

The great Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two autobiographical novels and envisioned a third, set in America. Why didn’t he write it?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In