Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

Long before Jerusalem’s skyline was punctuated by high-rises and cranes, the Holy City was already a crowded place. One of the wonders of Second Temple Jerusalem, as the rabbis tell it, was that despite the throngs of pilgrims, “No one ever said to his fellow: ‘The place is too cramped for me to lodge in Jerusalem.’” Jostling for space among a sea of visitors one recent Sunday afternoon at the Met’s fall blockbuster, Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven, I could have benefited from just such a miracle.

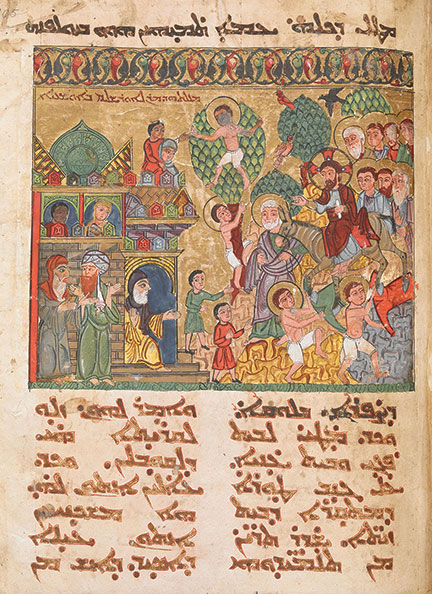

The front cover of the museum catalog is an eschatological Jerusalem scene that paints a diverse, dense urban space: Black, brown, and white people sporting turbans, togas, gowns, or just their underwear sit on stoops, converse on street corners, and cavort in the trees. The 13th-century lectionary (a selection of the Gospels to be read in church) from which the image is taken was composed in Syriac, one of many languages and scripts used in polyglot Jerusalem. Medieval eyewitness accounts frequently commented on the town’s confusing babel, and multilingual phrasebooks gave visitors the confidence to ask locals anything from “how much does it cost?” to “woman, let me sleep with you tonight.”

One of the places flooded by medieval Jerusalemites was the city’s famed vaulted marketplaces. The exhibit opens with a pile of glittering Fatimid coins surrounded by a gallimaufry of everything that money could buy: metal cooking sets, complete with pestle and mortars; serving platters inscribed in Arabic and customized with European coats of arms; medieval “selfies” with tourists’ own visages painted onto icons alongside Virgin and Child; and plenty of bling. (I overhead an enthusiastic conversation between a well-coifed mother and daughter in front of a pair of precious bracelets that could just as well have taken place down the street, in one of the luxury stores lining Fifth Avenue.) Opening an exhibit on the Holy City with a mock shopping expedition may seem like an unusual choice, but it is well-grounded in archeology and anthropology. Even Roman Jerusalem, with its colonnaded Cardo, was a shopper’s paradise, while alternating binges of prayer and procuring has always been part of religious pilgrimages.

Indeed, the crowded diversity of life in medieval Jerusalem was nothing short of remarkable, and the contemporary cliché of “Jerusalem of three faiths” does not do justice to its multiplicity. Apart from ancient tensions with the Samaritans, the city’s Jews were sharply divided into Rabbanites and Karaites—a sect of Bible “readers” (hence the name kara’im, from the Hebrew word for reading) whose sages rejected rabbinic interpretation and drafted penetrating biblical commentaries, some of which are expertly presented at the Met. From the opposing Jewish camp, major rabbinic figures came on pilgrimage. In the early 1200s several French and English rabbis actually moved to Jerusalem, and later in the century towering Catalan exegete Moses Nachmanides helped to re-establish Jewish life in the city, founding the synagogue that still bears his name. During the exhibition’s timeframe, Jerusalem was ruled by the Ismaili Fatimids, won back from the Crusaders by a Sunni of the Shafi’i school named Saladin, and led by the Sunni Mameluks, all while Sufis and other Islamic groups passed through the city gates. Christian communities were still more numerous and fractious, counting Greek, Armenian, and Syriac Orthodox, Copts, Ethiopians, and Roman Catholics, along with a large array of pilgrims, some of whom took up residence in the city. This splendid assortment, as the audio guide concretizes, was crammed into a space no larger than midtown Manhattan.

of Oxford.)

What are we to make of Jerusalem’s multitudes? Curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that the city’s crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism. There is indeed evidence of cooperation and even genuine caring across ethnic and religious borders. Muslims introduced Jewish pilgrims to some of the area’s less-known holy sites and, in an enactment of Abraham’s hospitality, dished out hot lentils from gargantuan soup pots to hungry pilgrims, regardless of persuasion. Symbols of other traditions were acknowledged and sometimes appropriated in surprisingly ecumenical ways: Christians called the Islamic Dome of the Rock “Solomon’s Temple,” Jews fittingly referred to it as Midrash Shelomo (King Solomon’s Study Hall). Even when a religious community was forcibly banned from the city, there was almost always a saving grace. Saladin’s expulsion of Christians from Jerusalem was incomplete, as he decided to allow Eastern Christians to remain. Some years later, Jerusalemites even saw a power-sharing arrangement between the two otherwise clashing faiths. And yet, the fundamental set of dynamics during the four centuries on display was one of bloody conquest, banishment, repossession, and reconstruction.

Boehm and Holcomb are trained medievalists and certainly not naïve about the brutish carnage wrought by crusade and counter-crusade. But as aesthetes, they insist on looking beyond interreligious violence toward the dazzling beauty of artifacts. The catalog makes a point of the exhibit’s arrangement, which is not chronological, confessional, or geographical, but thematic, mingling the objects of different times and faiths. It is also no coincidence that museum-goers must snake through fully five rooms before arriving at the disconcertingly beautiful “Drumbeat of Holy War” gallery.

Having worked for years in an office that overlooked some of Jerusalem’s most recent violent spasms, I am sympathetic to this act of prayerful fancy. Yet wresting medieval Jerusalem from troubling contemporary events, the city’s complex history, and, most problematically, its very physical presence in the world is purchased at the price of showing a place that is not this-worldly or other-worldly, but in no world at all. Although the show is creatively illumined by “windows” of classic Jerusalem views projected on exhibition walls, the overall lighting is dim; the actual city’s famously blinding light is essentially blacked out. This allows Boehm and Holcomb to project stirring shadows from Latin and Ethiopic crosses, but it also makes the exhibition rooms feel like an aquarium. Consistent with these aesthetics, the exhibition does not use present-day maps to explain the topography of the city, nor are there models—old-fashioned or digital—that might give viewers a peek inside a church, synagogue, or mosque.

The presentation of a crowded, medieval Jerusalem banished from time and space is disorienting as well as paradoxical, for what is a crowd if not too many people crammed into too tight a space at the same time? Isolating the city chronologically and geographically is still more awkward, since the story of Jerusalem and its art is essentially a tale of a luminous place striving to overcome the depredations of time.

The exhibit is strongest in a gallery labeled “The Absent Temple,” which confronts the city’s unique time-space conundrum by focusing on Jewish imaginings of the destroyed Second Temple. Here viewers are treated to some of the finest illuminated Hebrew manuscripts in the world, where perfectly symmetrical city gates balance on the backs of sinuous lions, and precise drawings of Temple implements push against the margins of the page. For Jewish scholars, perhaps the highlight of the entire show is Maimonides’ sketched-out visualization of the Temple plan in his own handwriting; for the more literarily inclined, an interview reflecting on the “present absence” of the Jewish Temple with Reuven Namdar, whose Hebrew novel Ha-bayit asher necherav (The Ruined House) won the Sapir prize last year, is inspiring.

Crowds don’t just mean pluralism, they mean competition—for space, resources, legitimacy. The day I attended the exhibit I passed two women in Muslim head coverings lovingly examining some of the show’s enormous Qurans, a bareheaded bearded man devoutly explaining the significance of some scenes carved onto gilded reliquaries, and an older couple complaining about the underrepresentation of Jews in the exhibit, as if debating the coverage of CNN or The New York Times. Given the relative population sizes and, to be frank, differing levels of artistic aptitude, I actually think the curators represented medieval Jewry and their cultural output honestly and respectfully. But of course, that is beside the point, since the couple was expressing the most natural of sentiments when it comes to Jerusalem. By ignoring the mysterious, profound, almost physical pull of Jerusalem the place, this expertly arranged assemblage of beautiful things never completely succeeds in explaining why crowds flocked to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages and why they continue to gather there today.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Harvard, SNCC, and an Antisemitic Cartoon

How did Harvard students end up using a decades old antisemitic cartoon in their anti-Israel activism?

Perpetual Motion

Remembering Yaakov Elman, who changed the way we study Talmud.

Ireland and the Promised Land

Why isn’t Israel more like America, Jews from that country wonder. In his ambitious new book, Alexander Kaye instructively raises the question of why Israel isn’t even less like the United States.

The Abrams Case and Justice Holmes’ Philo-Semitism

In 1919 Oliver Wendell Holmes changed his mind and in so doing transformed the law of free speech.

gwhepner

LIBERAL AND CONSERVATIVE HEARTS

Some people wear their liberal hearts upon a sleeve,

but conservatives will often wear theirs in a part

of them that's hidden, since their liberal friends believe

that views that are conservative impart

to those supporting them a character from whom

them must as they would from fiend depart,

designating him to PC doom.

Views that are not on the liberal chart

have trumped them recently, and boom.

Instead of falling from the appplecart,

they please a lot of people who consume

what liberals all reject as being far too tart.

I wish someone could find ad a modus viv-

endi between those with a liberal heart

and those who're cardiacly conservative,

so neither need be CPR'd.

Brain death has often been a problem from which both

have suffered by perhaps they could restart

their heartbeats, leading to their brains' regrowth,

if they were far less smug and far more smart.

[email protected]