A “New History” and Old Facts

On May 15, 1967, Israel’s long-simmering border conflict with Syria and its PLO clients came to a boil when the Soviet Union falsely warned Syria and Egypt that Israel was about to carry out a large-scale attack on the Golan Heights. In response, President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt advanced his army into the Sinai, which had been de facto demilitarized since the end of the 1956 Sinai-Suez War. A few days later, emboldened by waves of popular indignation across the Arab world, Nasser expelled the UN Emergency Force from the Sinai and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, thus blocking Israel’s maritime access to the Indian Ocean through its southern port of Eilat. Taken together, Nasser’s actions created the sense of an imminent, existential threat to the State of Israel. Prime Minister Levi Eshkol’s government regarded the actions as cause for war.

American attempts to defuse the crisis led nowhere, and, once Syria and Jordan (with the material support of other Arab states) joined Nasser, Israel had no choice but to strike first. Its surprise air attack against Egypt’s air force on the morning of June 5 lasted three hours and destroyed most of it, giving Israel air dominance as the IDF launched its ground forces into the Sinai—an offensive that lasted four days and ended with the devastation of the Egyptian army and the occupation of the entire peninsula. At the same time, and in response to shelling by Jordanian artillery, the IDF launched an attack that ended in three days with the occupation of the West Bank, including east Jerusalem. Finally, Israel took the Golan Heights, in a battle that ended six days after the war began.

This, at least, is the story that has been told and retold by the authors of both older and more recent accounts, and it is this story that Guy Laron attempts to upend by placing it in the larger context of Israel’s military plans in the late 1950s and 1960s, as well as the Cold War competition between the United States and the Soviet Union for influence in the region. The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East, which Yale University Press brought out shortly before the recent 50th anniversary of the war, is an attempt to thoroughly revise our historical understanding of the conflict.

Revisionist histories of Israeli–Arab wars are, by now, a familiar phenomenon. The 1948 War of Independence, the longest and most complicated war in Israel’s history, has received the greatest attention, and for good reason. The culmination of decades of Zionist efforts to create a Jewish state, it established the contours within which Israel would exist for the next two decades. It also marked the beginning of the Arab–Israeli conflict and the Palestinian refugee problem. The first histories of the 1948 war celebrated it as the victory of an Israeli David over a host of Arab Goliaths. But the opening of Israeli and British national archives in the 1980s allowed a group of “New Historians” to challenge the earlier narrative. They argued that Great Britain’s policy toward the Jewish community in Palestine tilted much less toward the Arabs than had been previously believed; that Israeli forces had not been vastly outnumbered by the Arabs, and may have even been the superior fighting force; that the struggle between the IDF and the Arab Legion of Transjordan (the best Arab army in that war) was not a fight to the finish but one that was circumscribed by tacit cooperation between the two sides; and, most significantly, that Israel was largely responsible for the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem. The debate between traditional and “new” historians has continued for a quarter of a century now, yielding an ongoing stream of important studies.

The Yom Kippur War of 1973 has also drawn intense scrutiny, albeit for different reasons. The most traumatic event in Israel’s history, it was a personal horror for many of those who fought in its bloody battles and yielded a great many published accounts. Some were personal memoirs, while others focused on specific battles. Recent years have witnessed a wave of well-documented historical studies. Most important among them were Shimon Golan’s semi-official 1,350-page history of the decision-making of the IDF high command during the war and Hagai Tsoref’s recent official biography of Golda Meir, Israel’s wartime prime minister.

A great deal of the controversy surrounding the 1973 war focuses on the reasons for the IDF’s catastrophic unpreparedness for the massive surprise attack launched by Syrian and Egyptian forces on the afternoon of October 6. While an official commission of inquiry, led by Israel’s Supreme Court president Shimon Agranat, concluded already in 1974 that the central failure was the lack of a timely warning from intelligence services, more recent theories lay the blame mainly at the feet of Prime Minister Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan. None of these theories—some wilder than others—is really supported by the evidence, but they continue to fuel a vigorous Israeli public debate every fall, a quasi-ritual event that coincides with the approach of the Day of Atonement.

In sharp contrast to 1948 and 1973, Israel’s incursion into Sinai in 1956 (the only occasion on which it ever joined its armed forces with those of Western powers to defeat its enemies) is an almost forgotten event. Similarly, the Lebanon War of 1982, in which Israel drove the PLO out of the country but failed to establish a new regime led by its Christian allies and ended up in a quagmire, has so far yielded only a few important scholarly studies.

The Six-Day War stands somewhere in between the most and least examined of Israel’s wars. One of the greatest military victories in modern times, it was a breathtakingly dramatic event that changed the shape of Israel and the Middle East. Inevitably, many books have been written about the weeks of crisis that preceded the war as well as the fighting itself, but most of them came out shortly after the war ended. In contrast to the reinterpretations of the 1948 and 1973 wars, the opening of the archives in Israel, Egypt, and elsewhere did not inspire reinterpretations of the 1967 war. Thus, Michael B. Oren’s Six Days of War, published in 2002, and Tom Segev’s 1967, published five years later, provided important new synthetic narratives, with their own distinctive emphases, but they did not radically change our understanding of what happened and why.

The first attempt to challenge the core narrative of the Six-Day War came on its 40th anniversary, when Dr. Isabella Ginor (who is a doctor of dentistry) and Gideon Remez, an Israeli foreign affairs journalist, published Foxbats over Dimona: The Soviets’ Nuclear Gamble in the Six-Day War. Differing with all those who maintain that the Soviets were surprised by the swift escalation of the crisis and tried to contain it, Ginor and Remez claimed that the Kremlin had planned to provoke a war in which Israel’s nuclear reactor in Dimona would be destroyed. But once the Egyptian air force was demolished in the war’s first hours, it had to abandon the plan. This quickly met with sharp criticism by experts who pointed out that Ginor and Remez had cherry-picked from largely anecdotal evidence and ignored all of the evidence and research that ran counter to their theory. Even the book’s title was sloppy: The Foxbat (MiG-25) entered operational service only in 1970, and the first Soviet reconnaissance flights over Israeli targets did not take place until 1971. As Galia Golan, a renowned expert on Soviet policy in the Arab–Israeli conflict, put it, the book “makes a great story . . . appears authoritative and will likely be believed in many circles, as often happens with conspiracy theories. That the thesis is true, or even logical, is another matter altogether.”

Guy Laron’s book is a more subtle work of scholarship than Foxbats over Dimona (and much less inventive), but it suffers from some similar flaws. Distinguishing his work from “all the books” about the war that focused on the events between May 15, when the crisis erupted, and June 10, when the war ended, Laron maintains that two key sets of developments—stormy civil-military relations in Syria, Egypt, and Israel, and the economic crises besetting Egypt and Israel—explain the lead-up to war. The first involves the growing tension in three countries between bellicose officers and more-moderate civilian leaders. The second explains why it became so hard for Nasser and Israeli prime minister Levi Eshkol to control their supposedly trigger-happy generals.

In attempting to validate his claims, Laron takes the reader down a long and winding road that includes, among other things, the history of Syria since World War II and of Egypt since the early 1950s; American monetary and foreign policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (with a baffling excursion into U.S.-Indonesia relations); the rise and fall of Nikita Khrushchev; and Soviet foreign and economic policies, including aid to Guinea in Africa. All of this is in service of Laron’s implausible contention that the global debt crisis of the 1960s, together with changing patterns of foreign aid from the United States and the USSR, created the conditions for economic crises in Egypt and Israel, which led to the crisis that preceded the war.

The first problem with Laron’s narrative is that it stands on very shaky historical ground. It is true that by 1967 Nasser had lost prestige, but the main cause for this was not Egypt’s economic crisis but a series of political failures, including the break-up of Egypt’s unification with Syria in 1961, Egypt’s endless and unpopular intervention in Yemen’s civil war, and the rising challenge of the Baathist

regimes in Syria and Iraq. His claims about Israel are also problematic, not only because most of the IDF generals identified with Eshkol’s Alignment Party, but also because they recognized the supremacy of Israel’s political echelon. This is not to say that the stormy relations between generals and civilian leaders or economic crises in Egypt and Israel had no impact, but to frame the story of the 1967 war around them is quite far-fetched.

A second problem with Laron’s narrative is the wearisome journey that he takes the reader on in attempting to prove his thesis. It involves too much information about too many irrelevant issues and haphazardly jumps from one topic to the next. The result is that he devotes the same number of pages to Nasser’s crucial decisions to advance his army into the Sinai, demand the removal of UN forces from the border, and close the Tiran Straits as he does to Israel’s 1954 Lavon Affair, which is irrelevant to the story. No wonder that we only get to a very partial 17-page discussion of the war itself at the very end of a book called The Six-Day War.

Laron’s book is also filled with factual errors. His very first paragraph claims that during the war’s first three hours, “Israeli aircraft wiped out the entire air forces of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq.” In reality, during these three hours 284 out of 419 Egyptian aircraft were destroyed, and none of the aircraft of the Jordanian, Syrian, or Iraqi air forces was engaged in those early few hours of the war. In one of the book’s last paragraphs, Laron notes that in the Yom Kippur War, “60–80 Israeli tanks were supposed to stop” the Syrian offensive, while their actual number was 177. In between the first page and the last, there are dozens of similar errors. Some, such as the claim that Syria lost seven MiG-21 fighter planes in dogfights with Israeli pilots two months before the war (it lost only six), are merely sloppy. Others show an alarming lack of expertise. Thus, for example, when Laron attempts to show that Soviet arms sales to the Arabs were mainly profitable ventures, he notes that between 1955 and 1967, the USSR sold Egypt MiG-15s, MiG-17s, and MiG-19s, which were all largely obsolete by June 1967. What he omits is that by that time, Egypt had also received more than 200 MiG-21s, the most advanced Soviet aircraft at the time.

These are trifles, however, when compared with the book’s deeper, thematic flaws. Laron’s principal contribution is to advance a narrative so poorly substantiated as to border on conspiracy theory. In essence, he claims that although Ben-Gurion realized after the Sinai withdrawal in 1957 that Israel would not be able to annex territories that it would occupy in future wars, “the [IDF] General Staff had never let go of the plan to expand Israel’s territory.” It repeatedly updated contingency plans “which envisaged the annexation of Sinai, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights.” This policy, we are told, received a boost in the early 1960s when a coalition of expansionists gained power. It consisted of generals from the Palmach (the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv) driven by Yitzhak Rabin; the Palmach commander and now leader of the Achdut Ha-avoda political party, Yigal Allon; and the kibbutzim of Achdut Ha-avoda, which wanted to both expand its farmland and demonstrate its continued indispensability to Israel’s defense. Together, they conspired to provoke the Syrians into shelling Israel. “Every barrage of artillery that landed on Ahdut Ha-Avoda settlements,” Laron writes, “seemed to prove that the kibbutzim were still Israel’s shield and armor” and provided another excuse for an attack on Syria.

This expansionist outlook was bolstered by the IDF’s military intelligence branch (Aman), whose “assessments of the intentions of Arab states,” Laron contends, “have always been politically skewed.” Aman’s director, Aharon Yariv, who owed his loyalty to Rabin, developed a paradigm according to which Nasser would avoid a confrontation with Israel as long as the Egyptian army was mired in the civil war in Yemen, which had begun in 1962. This assessment gave the IDF a free hand to escalate hostilities in the north, allegedly in order to create the conditions for a move against Syria without having to worry that it would have to fight with Egypt as well.

Levi Eshkol, the dovish prime minister who, under the pressure of his predecessor David Ben-Gurion, struggled to portray himself as a tough leader, yielded to the pressure of this group. “In December 1966,” Laron tells us, “the coalition of Palmach generals and settlers won a victory when Eshkol gave Rabin permission to breach the ceasefire” in the demilitarized zone on the Syrian border. The result was a series of escalating incidents between Israel and Syria, and the Fatah terrorists it sponsored, culminating in the crisis that led to the war.

This is a fascinating narrative. Indeed, had Laron, like the New Historians of the 1948 war, been able to base it on new evidence, his book might have deserved to become a central text in the history of the Arab–Israeli conflict. Unfortunately, he has provided nothing of the sort. Instead, his theory is based on a biased selection of previously published sources, mostly in Hebrew and thus beyond the independent assessment of most American and European scholars. Anyone familiar with the documentary evidence will instantly recognize his account as groundless.

That the IDF acted aggressively along the Syrian border in the years prior to the Six-Day War is no secret. An excellent, thoroughly researched semiofficial analysis of this policy was offered by Ami Gluska, a retired IDF colonel, in his 2004 book Eshkol, Give the Order! (published in an abridged version in English by Routledge in 2006). While Gluska acknowledges that there were some generals who talked in the 1960s about occupying the West Bank or parts of the Golan, he never provides any support for Laron’s claim that the army’s goal was to trigger an expansionist war. In fact, he maintained the opposite.

After Israel was compelled to withdraw from the Sinai in 1957, there was a consensus within the military that acquiring territory by force was no longer a viable option. Gluska quotes Rabin himself, in a meeting in IDF headquarters in July 1965, saying that, “I don’t believe in the political option of holding a territory that was occupied by our own military initiative.” As Gluska and others have shown, the IDF’s goal was simply to compel Syria to stop providing a base for Palestinian terrorists.

When Laron, for his part, quotes a senior officer who described General David “Dado” Elazar, the IDF’s northern commander during the war, as having “had a very clear plan, to liberate the Golan Heights,” he takes this comment out of context and omits the rest of the quote. Unlike Laron, Dado’s biographer, Hanoch Bartov, in his book Dado: 48 Years and 20 Days, makes Dado’s motivations clear: “Not because of love of war but because in his perception the Galilee could not survive forever under the shadow of Syrian guns.”

Gluska summarizes military deliberations in the summer of 1966 in which Dado proposed to capture the Syrian territory used by Fatah as staging areas for attacks on Israel. He also makes it clear that annexation was not raised as a topic in these discussions, and that Rabin’s position was that however far they got into Syrian territory, they would inevitably withdraw: “If we withdrew from Gaza [in 1957] we will certainly withdraw from Quneitra.”

But if Israel had no plans to occupy and annex the Golan Heights, why did the IDF prepare only offensive plans for a possible war against Syria? The answer has far less to do with territorial expansion than with Israel’s military doctrine. Due to the country’s small size and severe lack of strategic depth before the 1967 war, the doctrine called for preemptive strikes and, whenever possible, immediately taking the fight into enemy territory.

Moreover, the IDF had no war plans for the conquest of the Golan Heights as such before late 1966. Its only war plan in the north, formulated in 1964 and dubbed “Axe,” envisioned the conquest of Damascus, which, needless to say, Israel never imagined it would hold permanently. If, as Laron claims, the expansionist generals intended to expand Israel only as far as the Golan Heights, why didn’t they plan to do so well in advance?

Besides preparing an offensive doctrine, the IDF had also cultivated an aggressive esprit de corps, especially with respect to Syria, which was the only Arab state that continued to occupy Israeli territory at the end of the 1948 war. From the moment the Baath Party took over in Syria in a military coup in 1963, and even more so after February 1966, Syria became more militant, as evidenced by its radical positions in Arab forums, its anti-Israeli propaganda, its attempts to divert the sources of the Jordan River and prevent them from flowing into the Sea of Galilee, and its support for PLO operations against Israel. And, unlike other Arab armies, the Syrians were using their guns in the Golan Heights to shell Israeli kibbutzim, causing heavy damage. The crisis that erupted in mid-May 1967, it is clear, had been created not by Israel’s expansionist intentions, but by the pugnacious stances assumed by both the Syrians and Israelis.

The coalition of generals and settlers that Laron describes as the driving force behind Israel’s expansionist policy was, in fact, nothing of the kind. It was basically an informal group of brothers-in-arms. True, the Palmach had been the incubator for the IDF high command in the 1960s and the spiritual father of the IDF’s aggressive esprit de corps. But the most militant generals in the 1960s, Ezer Weizman and Ariel Sharon, never served in the Palmach. Indeed, after retiring, both joined Menachem Begin’s Likud Party, the successor of the Herut movement, which was Palmach’s historical nemesis. Laron’s claim that the coalition tried to garner support for the kibbutzim of Achdut Ha-avoda also shows very little familiarity with the subject, since the kibbutzim that suffered most from Syrian fire were Tel Katzir, Ha’on, and Ein Gev, which were all affiliated with the Mapai party, not Achdut Ha-avoda.

Finally, Laron’s claims about tendentiously distorted intelligence ignore the fact that, unlike that of the United States, Israel’s intelligence community has no tradition of skewing assessments according to its leaders’ political needs. If anything, the opposite is true. Aharon Yariv’s characterization of Nasser’s strategy represented not his own personal conclusion but the product of Aman’s Research Division, whose analysts sincerely—and not unreasonably—maintained that Egypt would not intervene militarily in the Syrian–Israeli conflict as long as a third of its army was stuck in Yemen. In fact, Egyptian accounts reveal that Nasser’s generals also believed that they were not ready for war and objected to the closure of the Straits of Tiran. Aman and Yariv erred in holding to their paradigm despite clear indications that Nasser was under pressure to help Syria, but this was a professional mistake, not a political one.

Shortly after I finished reading Laron’s deeply disappointing book, the Israeli Government Archive released a slew of important new documents on the Six-Day War in advance of its 50th anniversary, most relevantly the protocols of the security cabinet meetings before, during, and after the war. Nothing I have read in these documents supports his thesis. Good revisionist history must rely on either new documents or an original interpretation that takes into account the preponderance of existing evidence. At its best, it is based on both. Regrettably, Laron’s volume is based on neither.

Suggested Reading

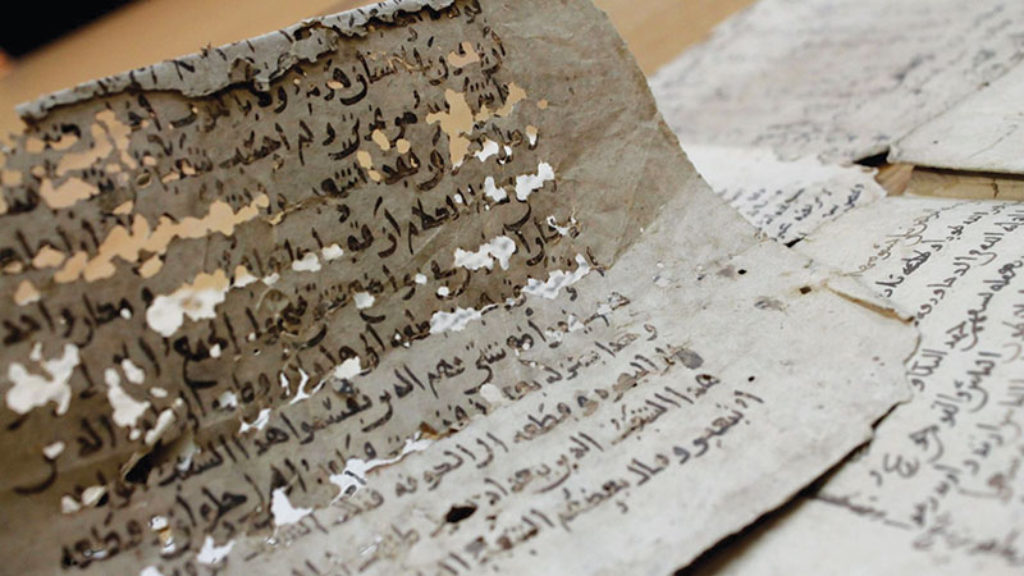

Afghan Treasure

Sometime in the 11th century, a distraught, young Jewish Afghan man named Yair sent a painful letter to his brother-in-law. Life had dealt Yair a tough hand, or maybe it was just his own bad choices.

Balm in Gilead

After reading through dozens of entries into our Reader Review Competition, we are pleased to announce that Gital Segal Rotenberg has been chosen as the winner. Her review of Dati Normali appears today. We thank all our readers who participated!

Blessing and Rebuke

Orphaned and imprisoned by the Nazis, while never ceasing as a poet, Paul Celan knew what it was to sing “above, O above / the thorn.”

Spinoza in Shtreimels: An Underground Seminar

A professor and three Hasidim walk into a bar—to study philosophy. True story.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In