Walkers in the City

On my first trip to Jerusalem, during a summer vacation from college, I stayed with relatives in Shikkun Nayot, a planned community for “Anglo-Saxon” immigrants not far from Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus. It was one year after the Six-Day War, and I was enchanted by the Western Wall. To reach the Old City, I would walk up Gaza Road on the southern edge of the Rehavia neighborhood, stronghold of the Ashkenazi intelligentsia. At the top of the road, at the corner of Keren Hayesod Street, was the monumental, neo-Renaissance Terra Sancta College built in 1926, crowned by a statue of the Madonna. After Israeli independence, it was rented to the Hebrew University and, for a time, housed its library. For the walker in Jerusalem, it became a landmark: “To get to downtown, turn left at Terra Sancta and go up King George, till you hit Richie’s Pizza.”

Herman Melville came to Jerusalem in 1857, when there was no downtown—the Old City was all there was. He was in a dark winter of the soul, following a string of literary failures, and was not enthralled: “In the emptiness of the lifeless antiquity of Jerusalem,” he scrawled in his journal, “the emigrant Jews are like flies that have taken up their abode in a skull.” I like to imagine that his contemporary Thoreau would have liked it better, had he ever stood on a green hilltop of Terra Sancta, in the course of a country ramble, savoring the view of Suleiman’s magnificent walls. As he wrote in the 1850s in his essay, “Walking”:

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks, who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering; which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the middle ages, and asked charity, under pretence of going à la sainte terre“—to the holy land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a sainte-terrer,” a saunterer—a holy-lander. They who never go to the holy land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds, but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere . . . But I prefer the first, which indeed is the most probable derivation. For every walk is a sort of crusade, preached by some Peter the Hermit in us, to go forth and reconquer this holy land from the hands of the Infidels.

For some holy-landers, Thoreau’s last sentence may conjure the memory of pogroms in 11th-century Ashkenaz or the specter of imminent jihad. But the dedicated saunterer seizes the transcendental metaphor, laces up his or her Reeboks, and seeks to redeem the contemplative spirit from the infidelities of modern life.

David Kroyanker is a native of Jerusalem, born into a German-Jewish émigré family in 1939. He is also a London-trained Israeli architect, urban planner, and author of some twenty books in Hebrew about the city. His two latest volumes, like most of their predecessors, are verbal and visual compendia of architectural and social history. The Jerusalem Triangle takes as its subject the central business district defined by Ben-Yehuda, King George, and Jaffa Road. Yet the title may also be construed as metaphor. These three streets—named for the Zionist pioneer, the British monarch, and the historically Arab city by the sea—represent the triangular tangle of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, all calling Jerusalem holy and going about their business nonetheless. The creative intersection of these cultures forms the ongoing subtext of Kroyanker’s magisterial project.

Between 1983 and 1993, he published Architecture in Jerusalem, six authoritative studies, rich in diagrams and drawings, organized by style and period, beginning with the Islamic conquest in 638 C.E. For example, European-Christian Buildings Outside the Old City Walls, published in 1987, traverses the city from the German Colony to the Russian Compound (where the British hanged Zionist fighters) to the 11th-century Eastern Orthodox monastery in the valley below the Knesset and Israel Museum where stood the tree, believers say, whose wood became the True Cross. (A hefty one-volume version for English readers was published in 2003 as Jerusalem Architecture.)

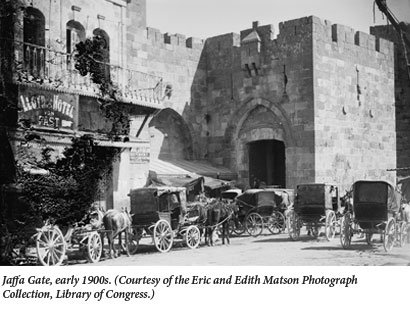

In 2000, Kroyanker began a handsome new series, describing Jewish neighborhoods in the western part of the city, street by street, building by building, showing and telling how things used to look and how they look today. These are aimed at the general reader, and most of them, like The Jerusalem Triangle, offer detailed walking tours. But this is not a book to carry in your purse or even backpack: It’s a bulky art book. You set it on a table, turn the pages, admire the many pictures, read the text, and saunter in your mind, to the Jaffa Gate, or Richie’s Pizza, or wherever. Then you take to the streets and practice the art of attentive walking.

The “Triangle” book is sixth in the series, following the volume on Mamilla, the old road to the Old City that has recently been turned into a fancy pedestrian mall. The other books have covered the Street of the Prophets, Old Katamon and Talbieh, Jaffa Road, and the German Colony, where I have lived since 1988. From Kroyanker I have learned much about the Templers, the peaceable, pious German Christians—not to be confused with the Knights Templar of the Crusades—who settled here in the 1870s. Today, original Templer homes are jewels of Jerusalem’s real-estate market. I was surprised to discover that the nondescript Mandate-era building at the end of my street, currently housing a fruit-shake bar, electrical shop, and kosher pizzeria, was once the headquarters of the Higher Arab Committee, the political organization established in 1936 by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Muhammad Amin al-Husseini. Here too are the Dajanis and other prosperous Arab families who built fine homes in the neighborhood before 1948. As I walk along Emek Refaim Street, to shop for vegetables or meet a colleague for coffee, I am able to remind myself that there was a different sort of life inside these picturesque old buildings, long before Caffit and Burgers Bar.

Overall, Kroyanker steers away from politics. For example, in The Jerusalem Triangle he quotes from Orientations, the memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs, who served as British governor of Jerusalem from 1917 to 1926: “There was not, when I took over, one single private car or telephone in Jerusalem.” He brings the same quote in his book on Jaffa Road, but in neither volume does he note Storrs’ about-face on Zionism, which he initially supported, then staunchly opposed. In the entry about the Ottoman-era house (on Shimon ben Shetach Street) where Vladimir Jabotinsky was arrested by British police in 1920, mention is made of Arab rioting and Jewish defense, but in Kroyanker’s project such matters are of secondary importance.

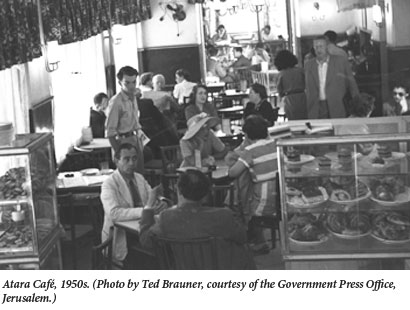

Kroyanker prefers to paint the British Mandate period in rosy tones, as an era of stylish architecture and European sophistication. He writes of the “Golden Age” of a bygone Jerusalem that outlasted the Mandate for decades, until the late 1960s. “In those days the ‘Triangle’ functioned as the beating heart of the little Jerusalem,” he writes, one-third the size of today’s in both area and population. His account, as he describes it, “attempts to awaken memories that have dimmed over the years.”

[This] naturally arouses—among many of its veteran residents as well as those who have left the city for other places—nostalgic memories of what once was; of a lively mix of cafés and cozy restaurants, elegant shops with high-quality goods, and many movie theatres, all gathered in a limited urban space. The nostalgia consists of a longing that is free of illusion, for a “Triangle” with a cosmopolitan aura and European character: without bazaars, fast food, pitzuchiyot [emporia of roasted nuts and seeds], moneychangers and shops of cheap clothing and gifts.

In other words, a Jerusalem redolent of Berlin and Vienna, an Ashkenazi preserve that flourished even after the city was divided in 1949 and dwindled when the city expanded after 1967. Kroyanker wistfully revisits the old cafés, nearly all of them gone, such as the legendary Atara on Ben-Yehuda that is today a Burger King. The Orion theatre on Shammai Street, now McDonald’s, was one of fifteen vanished movie houses (the author provides a map) that brought world culture to Jerusalem. It may have been at the Orion (or perhaps the Ron or the Zion) that in 1968 I saw The Day the Fish Came Out, an eccentric comedy about a nuclear accident by the director of Zorba the Greek. I remember fondly how the locals would signal their boredom by rolling empty bottles of grapefruit drink down the aisles.

Kroyanker’s “Golden Age” began in 1922, when the Greek Orthodox patriarchate, strapped for cash, sold large tracts of land to the Zionist Organization, enabling the development of Rehavia, Mamilla, and the area stretching from the Bezalel art school into the “Triangle.” King George V Avenue was ceremonially opened in December 1924 by the British High Commissioner for Palestine, Herbert Samuel, along with Governor Ronald Storrs and Ragheb Bey el Nashashibi, who served as mayor of Jerusalem from 1920 to 1934. Elegant apartment buildings, designed in the International or Bauhaus style by émigré Jewish architects, sprang up along King George. The Yeshurun Synagogue, also in the International style, was completed in 1936 on a plot of land purchased from the adjacent Ratisbonne Monastery, built in the late 19th century by a French convert from Judaism. Kroyanker’s tour of King George includes the “neo-Bauhaus” Beit Avi Chai cultural center, inaugurated in 2007, its design and dimensions in harmony with Yeshurun next door. Just south of these is the Jewish Agency building, completed in 1936. There were those at the time, reports Kroyanker, who regretted its modest proportions in comparison with the nearby Terra Sancta College and the gorgeous Palace Hotel, built in 1929 by the Higher Muslim Council across from the Mamilla Cemetery.

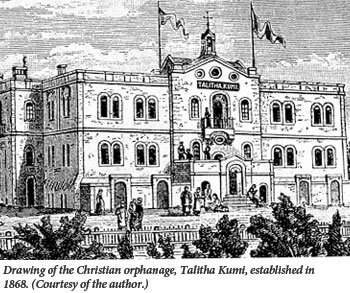

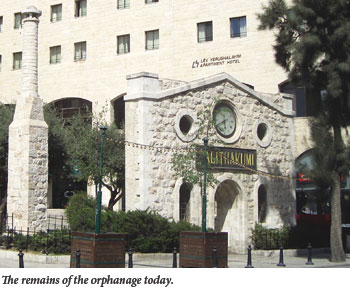

The Palace went out of business after a few years, unable to compete with the King David Hotel, which opened in 1931. The building later housed Israel’s Ministry of Industry and Trade and is currently being rebuilt as a luxury hotel, a project that has incurred the displeasure of architectural preservationists, Kroyanker included. The author was also among the city planners who opposed the destruction in 1980 of Talitha Kumi, a Christian orphanage established in 1868. Kroyanker devotes four full pages to illustrations of this splendid structure, in which the German architect and biblical archaeologist Conrad Schick combined Western and Middle Eastern motifs. (Schick’s striking home on the Street of the Prophets, now the Swedish Theological Institute, is a magnet for walkers in the city.) Today, what remains of Talitha Kumi is a fragment of its original entrance, including its clock, which stands by the bus stop near the Mashbir department store on King George—a “surrealistic composition,” in the author’s words, and “a warning signal for future generations, against the repetition of similar mistakes.”

|  |

Just prior to the book’s conclusion, in another long entry, Kroyanker addresses the Museum of Tolerance, originally designed by Frank Gehry, whose construction by the Simon Wiesenthal Center at the edge of Independence Park, on the site of a Muslim cemetery, has been delayed by a series of squabbles and budgetary problems. (Gehry quit in 2010.) Kroyanker offers an even-handed, apolitical account, noting that in 1927 the Mufti deconsecrated the site to permit the building of an Islamic university, including a medical school, intended to rival the newly founded Hebrew University. That grandiose project failed for lack of money. Opponents of the museum, writes Kroyanker, have argued that it is “inappropriate” for ethical reasons that a Jewish institution devoted to tolerance should be built on a site so fraught with inter-communal controversy. The demolition of Talitha Kumi and the continuing museum saga stand in unmistakable contrast to the general tenor of Kroyanker’s book, its amalgam of pragmatism and nostalgia that subtly constitutes a political ideal of its own: Jerusalem as a triangular city, to be shared by all.

In 1968, on my walks to the Western Wall, I would go down Agron Street alongside Independence Park and then reach the Old City’s Jaffa Gate via Mamilla Street. From the 1948 War until 1967, in the divided city, that street was truncated at the edge of no-man’s land by a concrete wall. Previously a bustling commercial area, it became a neighborhood of poor immigrant families. By 1968, the barrier was gone, but the street remained rundown. A few buildings stood out. On the left was the imposing Hospice St. Vincent de Paul, a convent and orphanage completed in 1911. Past that was a large house with impressive Arabesque windows and grillwork. It was built in 1898 by Herbert Clark, a diplomat and travel agent, who was one of the few members of the short-lived American Colony in Jaffa to stay in Palestine. (Most fled home in 1867 on the Quaker City, the ship made famous by Mark Twain in The Innocents Abroad.)

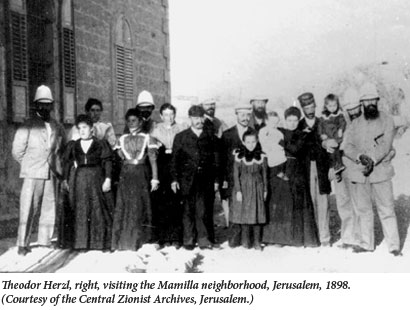

These buildings I barely remember from 1968, but the scores of photographs in Kroyanker’s Mamilla book are a prod to memory and a corrective to its tricks. There is a color picture of a faded stone wall, with graffiti that I do recall vividly: Makom kadosh/asur l’hashtin po (“a holy place/urinating here is forbidden”). The caption places the wall in the alley beside a Moroccan synagogue called Brit Shalom. Yet in my mind, the “holy place” graffiti was conflated with the adjacent Marx-Stern House, where Theodor Herzl stayed in 1898 during his one brief trip to Palestine, when he tried and failed to sell his Zionist plan to the visiting Kaiser Wilhelm II. For me, at age 20, the house was second in sanctity only to the Kotel.

It was built in the 1870s, explains Kroyanker, by the German Jewish Marx family, and was among the first homes in the Mamilla area. Herzl, upon arriving in Jerusalem, stayed for one night in the Kamenitz Hotel on the Street of the Prophets. It was filled with Ottoman officials who made him nervous; moving to the Marx house afforded greater privacy. Eventually the property was handed down to the Stern family, relatives of the Marxes. In 1950, in an official ceremony, a plaque was affixed that designated the house as an historic landmark. In 1970, it was expropriated by the city, and in 1990, following years of protest and litigation, the Israeli Supreme Court allowed the dismantling of the house as part of the massive overhaul of Mamilla. Its stones were numbered and stacked in a nearby lot. In 2007, the building was reassembled, and today, in the Alrov Mamilla pedestrian mall, it houses a café, a Steimatzky bookstore, and a meat restaurant simply called Herzl—in effect, the Herzl Bar and Grill.

Kroyanker does not elaborate on Herzl’s stay in Jerusalem; it’s not that kind of book. Interested readers may consult the standard biographies, or better yet, Herzl’s famous diaries, pages of which were penned in the Marx house. Consider these entries from October 31, 1898:

Yesterday the Sephardic Rabbi Meir was among the visitors who have been calling on me at the Marx house. He explained the attitude of the local Grand Rabbis to me: They don’t want to incur the displeasure of the Turkish government. Amused, I said: “In order not to cause the gentlemen any embarrassment, I shall also omit paying them a visit.” . . .We have been to the Wailing Wall. A deeper emotion refuses to come, because that place is pervaded by a hideous, wretched, scrambling beggary. . . . Yesterday evening we visited the Tower of David. At the entrance I said to my friends: “It would be a good idea on the Sultan’s part if he had me arrested here.”

Whether or not his friends got the hint, it seems clear that Herzl had in mind Shabbtai Zevi, who on the eve of Passover in 1666 was locked up in the fortress of Gallipoli by the Turkish Sultan Mehmet IV. Many rabbis, in Jerusalem and elsewhere, rejected Herzl as a dangerous false messiah who dared to hasten the Redemption. Yet Herzl relished the connection and understood its enduring power.

In Mamilla’s heyday, under the British, Arabs and Jews turned the area into a thriving business district. Eliyahu Shama’a, from Aleppo via South America, opened a commercial center situated just south of Mamilla Road, near the present site of Hebrew Union College; a side street today bears his name. Shama’a advertised his clothing and textiles in Hebrew under the Herzlian slogan Im tirtzu ein zo aggada (“If you will it, it is no fairy tale”). Shmuel Havilio manufactured candy, specializing in halvah. The Tannous Brothers were “Chevrolet Distributors for Palestine”; Sukri Deeb & Sons Ltd. sold Buicks and Oldsmobiles. A photo from 1935 shows Arab villagers walking down Julian’s Way—later renamed King David Street—with a flock of unsuspecting turkeys, headed for the poultry market in the Old City.

Soon after Jerusalem was unified in 1967, planning to redevelop the area began in earnest, but the planners were anything but united in their goals and intentions. The master plan submitted in 1975 by architects Moshe Safdie and Gilbert Weil called for the destruction of nearly every building in the area—including the Marx-Stern house—and the construction of underground roadways and more than 150,000 square meters of commercial and residential space. Jerusalem’s mayor, Teddy Kollek, enthusiastically embraced the plan, but was challenged by his deputy, Meron Benvenisti.

Benvenisti did not believe that Jerusalem needed urban solutions of “megalomaniacal” mega-structures, and was not prepared to risk turning a sensitive historic area into a laboratory for urban architectural experiments whose success had not been established in other parts of the world. Benvenisti therefore turned to the staff of the city’s urban planning department . . . which was headed by the author.

Benvenisti, Kroyanker writes, wanted a way to develop the area that was “more modest, conservative, and simple.” The author and his team produced an alternative proposal that would have preserved most buildings on Mamilla Road but also called for the construction of hotels, apartments, and public spaces. Kollek called the plan “a stab in the back” and dismissed it outright. Benvenisti, in response, quit his post in 1978. In a section labeled “The Return to Reality,” Kroyanker gives his version of how Safdie agreed to tone down his ambitious plan and develop a compromise solution, which included the preservation of historic buildings on Mamilla Road and its conversion into a pedestrian mall linking King David Street with the Old City. For his part, Safdie later groused that Trafalgar Square, Rome’s Piazza Navona, and even Central Park would not have come about had their creators been similarly constrained by bureaucrats and committees.

But can Kroyanker’s narrative be trusted? Not only was he a player in the drama, but Alfred Akirov, who developed the Alrov Mamilla Mall which now sits atop the street in question, was a sponsor of his book’s publication. Indeed the final chunk of the book, packed with snazzy photos of the new mall, teeters on the brink of ad copy. Yet, the fact remains that the shopping arcade that connects west Jerusalem with the Old City, which many Jerusalemites thought was a crass idea, and whose construction was held up for years by convoluted snafus chronicled by Kroyanker, has turned out to be a big hit, even among the initial doubters. Insofar as the author helped bring it about, he has a right to be proud.

Moreover, all books about Jerusalem, from the Bible onward, have an agenda. This has never impeded—and has often enhanced—their capacity to stir emotions, provoke fantasies, and inspire constructive commentary. The Mamilla book, taken as a whole, is a caution against hubris and grandiosity; indeed it challenges the messianic temptations inherent in the Zionist project. After the Six-Day War, writes Kroyanker in his conclusion, Israelis were “intoxicated.” There was a “sense that anything was possible,” in the field of urban planning as well as the field of battle. In the end, however, it’s all about compromise.

At the bottom of King David Street, you enter the Mamilla Mall at Rolex. En route to the Jaffa Gate, you saunter through a globalized mélange of Ralph Lauren and St. Vincent de Paul, Tommy Hilfiger and the Herzl restaurant, North Face and Habanos cigars, Crocs and Gali shoes and Adidas, crowded cafés with postcard views of the Old City, sprightly muzak from unseen speakers. On the left is the Clark House, its splendid façade restored, now sporting upscale shops—indirect descendants of the sort that once filled the Triangle. Few saunterers will realize that this is where the concrete divider stood before 1967, though keen-eyed shoppers may notice that from now on the structures are low and conventional, an arcade plain and simple, adorned with swooping arches. At the end, walking past the international jeweler H. Stern, you arrive at steps, more than twenty. You climb them, like a pilgrim, and the muzak fades away and your inner Psalmist hums shir hama’alot, the Song of Ascent, as the Old City walls materialize before you. Throughout the mall, on the steps, and on the great bridging plaza that stretches to the Jaffa Gate, swells a mixed multitude of tourists and locals, Arabs and Jews. No-man’s land has become Everyman’s land. Saint-terre becomes sans terre, which “in the good sense,” as Thoreau says, means “equally at home everywhere.”

Finally, you enter the Jaffa Gate, perhaps noting the mezuza that has been affixed to Suleiman’s massive portal. Across from David’s Tower is Christ Church, built in the 1840s and the first Protestant church in the Middle East. Now enter the shuk or suq, the Arab market, narrow medieval streets with arches, spices, souvenirs—a continuum, it suddenly seems, of the Mamilla arcade, a futuristic fusion. As Walter Benjamin observed in his monumental, unfinished Arcades Project: “It’s not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past: rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation.” For the walker in the city, the journey is a jolt of oxygen, a starry-eyed antidote, if you will it, to Yehuda Amichai’s poetic verdict: “The air over Jerusalem is saturated with prayers and dreams/ like the air over industrial cities./ It’s hard to breathe.”

Suggested Reading

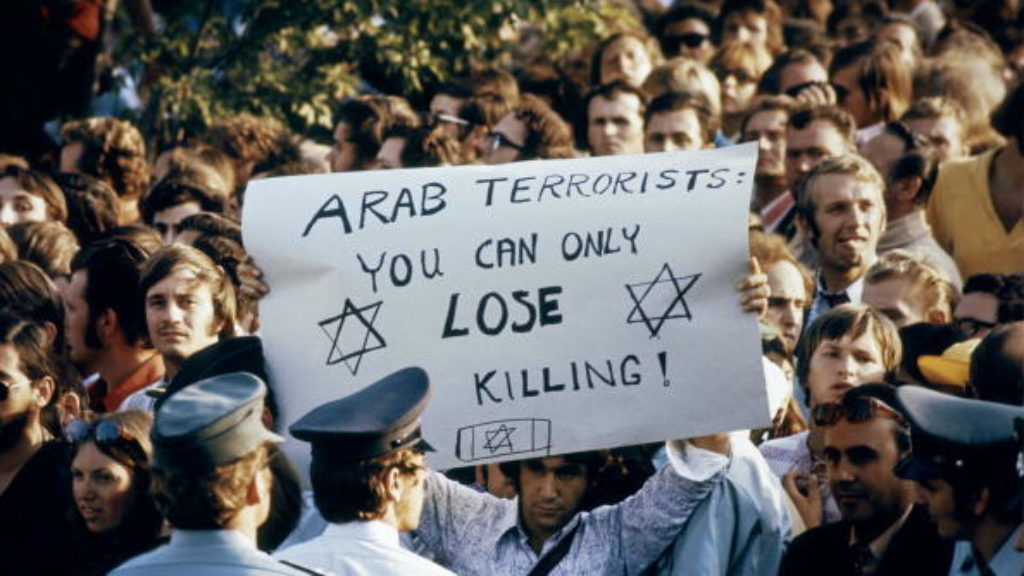

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

The Life of the Flying Aperçu

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role.

A Spy’s Life

Sylvia Rafael: The Life and Death of a Mossad Spy opens not with an intrepid secret agent about to pull off a bold maneuver, as books with such titles usually do, but with nine men gathered around a table in 1977, studying a picture of an Israeli agent.

Who Doesn’t Love Roald Dahl?

There’s nothing quite like the realization that what you thought was an empowering work of art is actually a 200-page exercise in trolling. It took me more than 30 years to figure out that I’d been trolled by Roald Dahl.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In