Who Is Man?

Saint Augustine believed that human beings constantly rebelled against God as a result of the sin of Adam and Eve. The ill-effects of that sin, Augustine famously contended, are symbolized by the male member—it rises on occasions when not desired and fails at moments when desire burns most intensely. In short, we cannot accomplish the good that we will while we find ourselves committing the evil we fear.

The rabbinic picture, we are frequently told, opposes such pessimism. In support of this a famous midrash commenting on Genesis 2:7 (“Then God formed man from the dust of the ground”) is often cited. The verb for formed (vayyitzar) is spelled here with two yuds, according to this interpretation, because God created humans with two inclinations (yetzarim): one for good and one for evil, and each person has the capacity to choose between the two. In his groundbreaking book, Ishay Rosen-Zvi argues that the rabbinic picture is optimistic, but also that it is actually far more complex than this citation would suggest. This idea of two warring inclinations did not really crystallize until the 3rd century, and it had a complex, literally demonic genealogy.

As a noun, the word yetzer appears in Genesis 6:5 in reference to the evil tendency of man’s thoughts, and in Genesis 8:2 God reflects that the yetzer of man’s heart is evil (ra) from his youth. But as Ishay Rosen-Zvi makes clear, neither of these verses nor any others in the Bible presents the yetzer as an independent entity, let alone an evil one. For that, we have to wait for the rabbis. But where did they get the notion? And at what point did they oppose it to a good yetzer?

Rosen-Zvi’s answer to the first of these questions takes us back before the rabbinic era, to Qumran, the community that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls. “My claim is that at Qumran yetzer occupies a middle ground between the biblical ‘thought’ and the reified rabbinic being.” The biblical understanding of yetzer, he shows, remained more or less unchanged as late as the early 2nd century BCE, when the Wisdom of Sirach appeared. But the sect at Qumran held to a cosmological dualism. Those on the side of good were believed to be elected by God and governed by the power of light, while the wicked were seen as the lot of Belial and constrained to do evil. This could “account for the election of the sect, but not for the depravity and sinfulness of its members.” The answer to the latter was that the yetzer tempted even the sons of light to do evil.

At Qumran, the yetzer hara fit into a demonological context, “as a counterpart of Satan, Belial, and the spirit of impurity—and in an anthropological one—as a component of human depravity.” The rabbis, for their part, refused “to accept grand cosmological models subjecting humans to external superhuman forces” and “left the yetzer alone to account for their sinfulness, thus making it the center of their anthropology.”

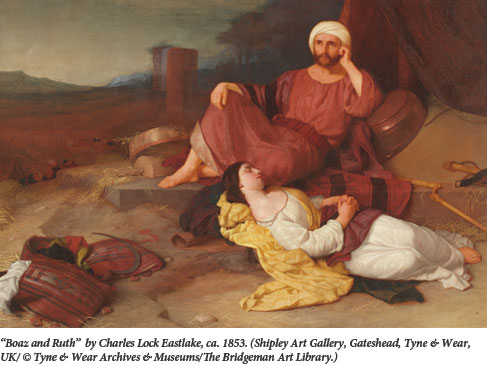

In early rabbinic literature, Rabbi Akiva preserved the biblical concept of the yetzer, while Rabbi Ishmael adopted a version with some simiarities to the Qumranic one. In Akiva’s usage, the yetzer was never qualified as “evil.” R. Ishmael, on the other hand, cast the yetzer in a darker light and frequently identified its power with the domain of the demonic. As proof of this, Rosen-Zvi cites a midrash from Sifre Numbers that describes the evil yetzer tormenting Boaz during the night that Ruth slept at his feet on the threshing floor. “Strong, sophisticated, and demonic as the yetzer may be,” Rosen-Zvi concludes, “it is still external . . . Boaz does not need a good yetzer to best his evil one; he struggles with it and defeats it himself.”

It is not Rosen-Zvi’s claim that fully developed demonic figures are at play in these texts. Satan is nowhere invoked as the one who orchestrates temptation. Rather, Rosen-Zvi uses the term in an extended sense to refer to a power that is “fully internalized” within the person. This is a subtle but crucial point. The yetzer is demonic but internal to the domain of the “self.” Unlike the pessimists at Qumran, the rabbis believed that it could be overcome with divine help. One was not at the mercy of nefarious cosmic forces operating outside the domain of one’s free will.

It is only in later stages of rabbinic literature that the notion of a good yetzer is regularly opposed to an evil one. In all of the earlier tannaitic literature there is only one text that speaks of such a competition in the sense of the midrash with which we began. In Mishnah Berakhot 9:5, we are told of the famous verse in Shema, “And you shall love the Lord your God, with all your heart and all your soul . . . ” (Deut. 6:5) that “with all your heart” means the two yetzarim, the one for good and the one for evil.

Some scholars have sought an external impetus for this innovation, but neither Qumran nor any other postbiblical source has ever been located. Others have suggested that the idea actually arose from close midrashic readings of the Bible. But these interpretations are found only much later, in amoraic sources and appear to be justifying a pre-existing idea. Moreover, such a fundamental claim about the nature of the human person is likely to have its origin in something other than intensive exegesis.

The two yetzarim of the Mishnah have to be considered in their literary context. The goal of chapter 9 as a whole is to counter any sort of dualistic cosmology. The second mishnah, for example, exhorts the reader to say a blessing for both good and bad tidings; the third mishnah rules that a benediction must be said for good and bad fortune, while the fifth mishnah provides the biblical source for these very obligations. It is within this fifth mishnah that we find our sole tannaitic reference to a two-fold yetzer. “This context makes polemic with dualistic doctrines quite fitting,” Rosen-Zvi concludes, saying:

A dual yetzer structure internalizes dualism and submits it to the free will of the person hosting the yetzarim. In this polemical, anti-dualistic context, it is quite understandable that the same homily that presents a rare dualistic model also present an exceptionally dialectic one. The evil yetzer is not necessarily an enemy, for it too can be enlisted in God’s service.”

Throughout this study, Rosen-Zvi argues against any particular linkage of the yetzer with sex, the early midrash concerning Boaz notwithstanding. Ultimately, however, in the Babylonian Talmud, especially in its latest editorial layer, the yetzer does become sexualized.

Eight out of nine narratives that mention the evil yetzer in the Bavli discuss sexual issues. Despite their variegated topics, they all present an image that is fundamentally similar: the yetzer appears as sexual desire, with which men, usually sages, are in constant struggle, and that demands external assistance or supervision in order to win.

Confirmation of the late nature of this development can be gathered from Syriac sources. As scholars have long noted, several Syriac Christian writers, who were rough contemporaries with the amoraim, utilize the rabbinic idea of an “evil yetzer.” Yet these Christian sources never identify the yetzer as having a particular role in sexual temptation, which is the domain of Satan alone. “Had the Jewish idiom any sexual connotation [in the early amoraic period],” Rosen-Zvi concludes, “it would be reasonable to expect it to [have left] traces in Syriac literature as well.” The conclusion seems inescapable—the linkage of the yetzer to sexual desire was an innovation of the final redactors of the Talmud.

Rosen-Zvi’s learned book opens up new vistas for the discussion of Jewish theological anthropology. His careful philological work traces the numerous connections between rabbinic and early Christian conceptions of human nature and sin. Ultimately, Rosen-Zvi emphatically endorses the view that the rabbinic conception of the human person is fundamentally optimistic.

Paula Fredriksen’s latest book is not a learned monograph like that of Rosen-Zvi. Rather, it is a concise and elegantly written history of how the early church understood the sinful character of humanity and the solutions it provided. Beginning with the New Testament, Fredricksen claims that Jesus is to be located securely within the Judaism of his day. His interests were focused on the restoration of Israel and its current plight as an occupied nation awaiting the fulfillment of its destiny. Paul of Tarsus radically expanded the picture by putting emphasis on the plight of the Gentiles and their inclusion in the salvation offered to Israel. In order to accomplish this, Paul developed a concept of sin and redemption that encompassed both

Israel and the nations. In Fredriksen’s account—which would be contested by many—Paul preached a universalism in which all would be saved.

Everything changed dramatically in the 2nd century when the church fully entered the Greco-Roman world and began to shape its teaching around the philosophical categories of Middle Platonism. The key players here were Valentinus, a gnostic theologian; Marcion of Sinope, an early Christian bishop whose teachings were ultimately denounced as heretical; and Justin Martyr, a “Church Father” and early defender of the Christian faith. Fredriksen’s final chapter engages two of the most brilliant thinkers of the early church, Origen and St. Augustine, who transformed this early discourse.

For Origen, humanity was created with an ethereal body that was subject to change. Before the creation of the material world, these spiritual creatures were sated with the goodness of God and yet momentarily turned from him, each in his own fashion. In order to rectify this error, God created the material world as a site for repentance and restoration. This explanation allowed Origen to explain why each person is so different despite having common origins:

Now since the present world is so varied and comprises so great a diversity of beings, what else can we assign to the cause of its existence except the diversity in the fall of those who declined from unity in dissimilar ways?

Our human bodies were not evil as the gnostics like Valentinus had asserted, they were the means through which our return to God would be won.

Origen also claimed that God intended every soul he had fashioned to be saved. But how could this be squared with free will? Clearly some persons will prefer rebellion over obedience. Origen countered that each soul was created by God and naturally tended toward the good. If that soul was re-incarnated a sufficient number of times, it would eventually come around and choose the path toward salvation. This doctrine found few followers and was eventually condemned by the Church. For this reason Origen never enjoyed the honor that his brilliance deserved.

Augustine is certainly the most important and influential figure that Fredriksen treats. What interested Augustine was the fact that human beings could know the good and yet be unable to choose it. The human will is damaged and easily conquered by the desires of the body, a condition we all inherit from Adam and Eve. (The fact that 90 percent of all diets and exercise programs go unheeded in spite of their obvious benefits would not have been a mystery to him.)

The answer to this problem, according to Augustine, was to be found in the “grace” of God. Drawing on God’s arbitrary preference of Jacob over Esau in Genesis, a choice made on the basis of no human action, Augustine argued that salvation was totally dependent on God. Humanity as a whole, he reasoned, was a “lump of perdition” and not deserving of eternal life. When God exercises his wrath, for instance in the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, it is not so much that God makes persons do evil as that he simply leaves them on their own. Their fallen nature will inevitably generate the sins.

As Fredriksen wisely observes, the question for Augustine is not how is God just in condemning the sinner, but how is God just in redeeming the elect? If both were equally culpable prior to the infusion of grace, what criteria did God use to justify Jacob but condemn Esau? Augustine’s answer is that it is a mystery known only to God.

Suggested Reading

Living Postcards

YIVO/Yeshiva University Museum's recent exhibit of pre-war home videos provides an extraordinary view into the lives of ordinary people.

Letters, Summer 2023

Outside, but Where?; Satmar Literacy; On the Interpretation of Freud, and More

History and Polemic: An Exchange

Eric Alterman and Allan Arkush have a heated exchange on Israel, American Jewry, and the role of a historian.

Orphan Soldiers

When WW II seemed all but lost, Britain knew that it had to take impossible risks, including turning Jewish refugees into crack commandos.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In