The Jewish Critic and the Devil’s Point of View

“What’s your name?” That’s the first question a Jew asks when he meets a complete stranger and offers him a sholem aleichem. It doesn’t occur to anyone to reply, “Why do you need to know my name? Are you planning to become my in-law? My name is what they called me when I was born and mind your own business . . .”

No Jew objects to invasive curiosity, the author tells us, because enforced intimacy is such a natural part of Jewish life that he assumes you have the right to know everything about a fellow Jew, mooch tobacco from him, eavesdrop on his private conversation and if the subject is business throw in an unsolicited word of advice. And this Jewish custom is by no means restricted to our life on earth: “What’s your name?” is the first question you’ll be asked at the gates of heaven and it was what the Angel asked Jacob before they started to wrestle. If that’s the first question posed in the beyond, it would have to apply as well to mortals, so I know that since this is my first foray into Yiddish literature I will be asked, “What’s your name, Uncle?”

“My name is Mendele!”

What I’ve quoted above is the opening of The Little Man (all translations are my own), a novel published in 1864 that marked the literary debut of its author and what many scholars, including my teacher the late Max Weinreich, designate as the beginning of modern Yiddish literature. To be more precise, I have quoted and then paraphrased from the revised version of the novel the author issued a few years later. But the gist of it remained the same: Mendele Mokher Seforim (Mendele the Book Peddler) introduces himself as a member of the tribe and assumes on that basis that he can carry on about his fellow members. We have never met this Mendele before, but as we are intimately familiar with the culture, he expects us to trust him, appreciate his wit, catch his references, and share his attitudes. In a few deft lines, the author sets up a figure so democratic you don’t have to look up to him, so familiar you don’t have to fear him, and so appealing you won’t realize you’re being flogged.

Mendele, the generic insider, was a creation of genius. In the premodern world’s most literate community, that of the Jews of Eastern Europe, no one was more inclusive, more all-encompassing than the Jewish book distributor who picked up his merchandise at the big-city publishers and then traveled through the Jewish Pale of Settlement to towns and villages where everyone—and I do mean everyone—awaited his coming. When he listed his wares you could see the breadth of his appeal: For the men he carried sifre ruml—an acronym for books for scholars and teachers (Rabbanim Umelamdim)—and also weekday and holiday prayer books, indispensable religious items such as phylacteries and prayer shawls, and mezuzas for the doorposts. For the women there were tekhines, books of common prayer, but also racy novels that were then beginning to circulate, as well as amulets, wolves’ teeth, and other items thought to bring good luck or ward off the bad. He also carried current merchandise for the younger crowd, polemical literature, and translated works of instruction. For children he offered little shoes and yarmulkes and some copper household items, such as ewers for washing hands. Thus, everyone, from scholars awaiting the latest rabbinic commentary to pregnant women who needed protective prayers, looked forward to the arrival of the man who also traded in news and gossip, and occasionally delivered some documents from a neighboring town. Mendele was the provider for male and female, rich and poor, learned and simple, young and old, urban and rural, traditional and modern Jews—this last division being of special importance to the story.

We may better appreciate the invention of Mendele the Book Peddler as the narrator of the first Yiddish novel if we compare his literary debut with that of Robinson Crusoe in what is considered the first English novel. When Daniel Defoe published this book under Robinson Crusoe’s name as “written by himself” he was readying his readers for a highly improbable adventure story, and to shore up the premise of realism he provided commonplace information about its fictional narrator—the drier the better:

I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and leaving off his trade, lived afterwards at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a very good family in that country, and from whom I was called Robinson Kreutznaer; but, by the usual corruption of words in England, we are now called, nay, we call ourselves and write our name “Crusoe,” and so my companions always called me.

Defoe had to build trust in the reality of Crusoe’s existence so that readers would suspend their disbelief and accept his fantastic story. Our real-life Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh also had to create a sense of realism, but so as to reveal his readers to themselves in an altogether familiar environment. He was asking them not simply to believe in Mendele’s reality, but to let him make fun of them. He proved his right to joke through his joking: Only an insider could be allowed to disparage Jewish rudeness and meddling and chutzpah and other unpleasant by-products of the very intimacy that he was exploiting.

Much has been written about Abramovitsh’s Mendele—the persona that swallowed its creator, the alias that displaced the author: What has gone under-reported is Mendele’s function as a platform for criticism so secure that its purpose goes almost unnoticed. The creation of “Mendele” gave Abramo-vitsh the freedom to expose the worst of Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement.

Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh started out as one of a small group of self-styled enlighteners, maskilim, who aspired to correct Jewish behavior in everything from cheder education to treatment of animals. Like many members of the Russian and Russian Jewish intelligentsia, he based his reformist goals on Western European ideas of progress. He was by nature severe: His secure and loving childhood had been cut short by the death of his father and his mother’s remarriage, which brought a sharp fall in family status. His traumatic discharge into hardship exposed him to some of the cruelest aspects of Jewish society. He spent hard years as a poor yeshiva student and ended up travelling with an itinerant hustler who tried to sell him off as a brilliant catch for a prospective wealthy bride. Although he escaped that trap, his first unhappy marriage ended in divorce.

Young Sholem put some of this bitter experience to creative use in Hebrew articles, reviews, and fiction. And then, as he tells it, “the wish to be of use to my people”—plus the temptations of a new, much wider Yiddish reading public—lured him into the arena of Yiddish fiction that was just starting up. In 1864, two years after the publisher Aleksander Zederbaum added the Yiddish insert Kol Mevasser to his Hebrew weekly newspaper Ha-melitz, Abramovitsh submitted Dos kleyne mentshele and launched his Yiddish literary career under the cover and name of Mendele—a traditional Jew, at 52 almost twice the author’s age when he created him.

When Mendele hits town in his first appearance, the local rabbi sends for him, saying, “God has brought you here just when you are needed!” The town’s wealthiest man, Isaac Abraham “Takif,” has just died, leaving an autobiographical will with instructions that it be delivered to the rabbi for public reading. Mendele is then urged to publish Takif’s will as a public service. Mr. High and Mighty—the implied meaning of takif—has not taken any chances but has waited until after his death to tell the story of his sleazy career. The confession begins with himself as a child trying to understand the “little man,” dos kleyne mentshele, the Jewish soul that adults are always talking about.

The first time I ever laughed aloud reading Yiddish literature was when the child pounds his mother’s back as she leans over the oven because he wants to knock the little man out of her eyes where he has seen his reflection. I know it doesn’t sound like much, but the slapstick works, and the boy’s failure to expel the homunculus teaches him the difference between literal and metaphoric language. By imitating those to whom the term is applied, Isaac learns the little man’s skills of sycophancy, dishonesty, and cruelty that take him step by step to the top of the Jewish social ladder. It is hard to pull off the literary contrivance of a self-incriminating confession, and this will never rank among the author’s great works, though it is an effective exposé of the kind of religious hypocrisy and abuse of authority that this schemer represents. What is interesting is, first, that despite the harsh critique of Jewish society, the figure of Mendele stays independent of this criticism, ready for any other good manuscript that will come his way, and, second, politically, that the satire stays strictly within Jewish community bounds. The Russian government does not come under assault.

To continue sour-cherry-picking through Mendele’s canon, let us consider Fishke der krumer (Fishke the Lame), a novel more problematic today than when it appeared in 1869, or in its revised edition of 1888. The English word “lame” masks the term krumer’s harsher connotations of misshapen and deformed. At the start of the novel Mendele’s wagon gets entangled with the wagon of fellow book peddler Reb Alter, setting up an entanglement of sentimental romance (that pities deformity) with premodern satire (that equates deformity with corruption) as the two men meet up with a third character, Fishke, whose story then takes center stage.

Heroes from the lower depths of society were staples of 19th-century literary realism, and Fishke fits that bill, a bathhouse attendant conned by the town into a marriage with a blind woman, Basye, who drags him into the society of professional beggars, pimps, and thugs. Fishke’s involuntary descent from underclass to underworld subjects him to the predatory cruelty of the Jewish beggar gang, but also highlights his heroic potential as he becomes the loving protector of a hunchbacked girl whom the gang has kidnapped. This wins him the special enmity of the gang leader, the Red Bastard, who is cuckolding Fishke with his wife. Trapped by the villain in a cellar and left for dead, Fishke is discovered by the book peddlers, whose horses have been stolen by the same beggar gang. The sentimental strand of the story approaches positive resolution when Reb Alter realizes that the hunchback whom Fishke has protected is the daughter he deserted many years earlier. On the plane of sentiment, this leaves us hoping that Fishke and a repentant Reb Alter will rescue the poor girl. But on the plane of criticism, the beggar gang is still out there at the end of the book, threatening Jewish life and reputation.

Here is where the novel risks as much censure as it dispenses. If the portrait of the wicked Fagin that Charles Dickens draws in Oliver Twist is an anti-Jewish defamation, what shall we say about a Jewish gang that exploits human disfigurement, whose vicious leaders—male and female—kidnap and enslave weaker members of a Jewish society that abets this criminality? Abramovitsh far exceeds Dickens or any other Gentile writer in his negative portrayal of Jews, for his Mendele knows more about Jewish society than any other writer of his time and can penetrate its darkest corners. In fact, it is not unusual for Mendele to stumble into some dark corner or state of inebriation in which he experiences a nightmarish vision of the reality that is already bad enough by the light of day. And he has the verbal facility to get the worst of it across. In the way solo instruments take off in jazz, Mendele takes over from Fishke’s description of what it is to be a beggar to riff for a couple of pages on Jewish beggar folk, from the infantry of foot paupers through the cavalry of horse-drawn paupers and all the types of spongers and moochers and indigents, including Hebrew authors who peddle their books door to door, culminating in Reb Alter’s summation that Kol yisroel—eyn kabtsn: “All Jewry is poverty (or beggary)—and that’s it.” Mendele declares the beggar’s pouch to be the symbol of the Jew.

How did Abramovitsh get away with it? How did Jewish readers put up with so disparaging a representation of themselves? Well, they did and they didn’t. The same year that Abramovitsh published his first version of Fishke he also wrote a play called The Meat-Tax about the corrupt Jewish administrators in a certain town who artificially raise the price on kosher meat, skim profits, bilk the poor, and denounce to the government authorities anyone who stands in their way. The play is shrill and adversarial, maskilic agitprop. Abramovitsh claimed that the locals who recognized themselves in the caricatures forced him and his family to leave Berdichev, and even if this was not strictly accurate, he did leave the city at that point and thereafter redirected some of his literary focus. But it was more than fear of Jewish reprisal that affected Abramovitsh’s political adjustment. When Odessa experienced the first modern pogrom in 1871 the governor of the province, to whom Abramovitsh had dedicated The Meat-Tax, did not stop the carnage. He did not turn out to be the benevolent ally who Abramovitsh had hoped would help him and his colleagues forcibly “improve” the Jews.

When Abramovitsh revised and expanded the Yiddish and later the Hebrew versions of Fishke, he included a sequence in which Mendele goes searching at night for Reb Alter, who is looking for the missing horses. After working himself into a nervous state worrying that he might miss the deadline for his book deliveries, Mendele drinks hard liquor on an empty stomach and cries with self-pity at the memory of his mother’s love for him. In this inebriated state he strays into a vegetable patch, where he takes a cucumber and is apprehended by a constable who hauls him into police headquarters. The officer in charge, just for the fun of it, shears off one of his payes. Mendele breaks down and cries a second time, for the earlock his mother once caressed that now lies on the floor. The Russian repents of his action, tries to comfort his victim, and bawls out the constable who brought him in over the “theft” of a cucumber. This is the only time the book steps into Russian officialdom, and the narrator, Mendele himself—not Fishke—is its victim.

Mendele is driven to tears by his impotence, his author by the knowledge that over and above whatever happens within Jewish society a far more sinister power controls it from outside. In the book’s merciless critique of Jews as a top-to-bottom society of beggars, this sadistic act of the authorities is so relatively mild that the Russian censor would hardly have paid it attention, yet there it is, in full view: the repressive, malevolent, and arbitrary political context within which Jews must operate, and the larger political and moral framework within which the Jews are found wanting. Abramovitsh admits it behind the excuse of drunkenness, because it might otherwise be construed as protest. Mendele can cry only when drunk because the rest of the time he must swallow his pride and function as a fully responsible adult.

We don’t know exactly when in the 1870s Abramovitsh wrote this chapter, but by the early 1870s he was situating his criticism of the Jews within the overarching political framework of tsarist rule. In contemporary terms we would say his politics had changed. Thus, in his 1873 masterwork Di kliatshe (The Mare), Mendele brings us the story of Isrolik der meshugener, a young and wholly rational young man who is driven to madness by the real-life political constraints that prevent him from becoming the reformer he aspires to be.

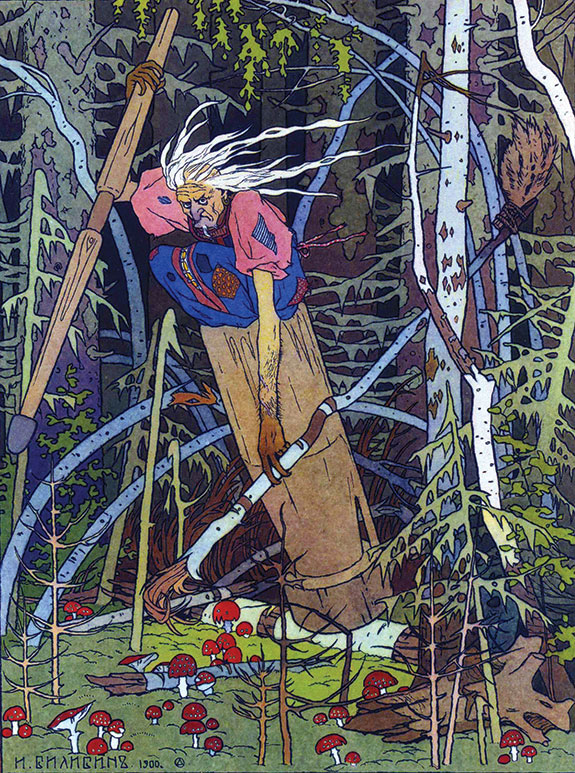

Isrolik’s mother wants him to hurry up and marry and become a dutiful Jewish householder. He wants first to study medicine, the exemplary healing profession, so that he may improve her life and the lives of Jews and Gentiles alike. He stuffs himself with required reading for the entrance exams but is foiled by the anti-Jewish examiners who require that he also demonstrate knowledge of Russian folklore—including of the witch Baba Yaga—a requirement whose only purpose is to cause him to fail. The shock of this injustice tips his fragile balance, and he suffers a mental breakdown. In that state of alleged madness, he “sees” a bedraggled mare being pursued and attacked by a gang of hooligans and yapping dogs. Isrolik vainly tries to chase them off. When the human and canine attackers tire of their sport and retreat, the Mare emits a human sigh, and surprises Isrolik by beginning to speak.

The Mare recounts how she was once a noble prince—“fine, handsome, intelligent mit ale mayles, with all the virtues”—until envious rulers had their sorcerers transform him into the Wandering Mare. Briefly restored by the great miracle worker who led her out of bondage to the Promised Land, the Mare was then transmogrified once again into her miserable state. When Isrolik asks her, “Vi lang—How long have you been in this condition?” the Mare replies, “Lang vi der yiddisher goles.” The Mare breathes life into the dead idiom: She has been in this condition for the duration of the Jewish exile, which is both the manifestation and the cause of her torment. This curse of exile—like Isrolik’s failure to pass his exams—is inflicted from the outside.

Isrolik is stirred and angered by the Mare’s desperate condition. A member in good standing with the Russian version of the Humane Society, he declares himself her loyal protector and advises her how to regain her standing: If only . . . if only . . . and he trots out the Jewish enlightenment agenda. If only she were to improve her appearance, reform her behavior, prove herself useful, and get a proper education, she would be accepted among the other steeds. But the Mare has had enough. Against her Gentile pursuers she has no recourse, but she will not submit to the false bromides of a fellow Jew. She accuses him of being disingenuous. His membership in high-minded groups did not help him drive off the dogs, so what is the real value of his goodwill? Other horses don’t have to prove their right to graze:

What do eating and basic needs have to do with education? What right do you have to prevent someone from eating, from breathing freely, until he masters some trick or other? Every creature that is born is a living thing. Nature has provided it with all the senses, all the organs, for its own use, to get everything it needs to live.

The Mare sums up her disquisition on natural rights with the phrase, “The dance performance does not precede the food”: Human rights cannot be earned.

Mendele’s Mare corrects the false premise of Isrolik’s rationalism. Jews may be in need of reform, but they cannot and should never have to prove their right to flourish. Isrolik should not be trying to whip up sympathy for the poor Jews on the one hand and blaming them for the aggression they inspire on the other. The principle of human rights for the individual citizen applies equally to minorities in the family of nations. Toleration and equal opportunity are the preconditions of citizenship, not rewards to be meted out by capricious authorities. Isrolik’s compassion for the Mare is no substitute for ensuring political equality.

“Wow!” exclaims the young man when the Mare concludes her peroration. “Why the devil’s gotten into you!” And at that point our Isrolik is whisked away by the Devil for the third and final section of the book, which constitutes the climax of his real education. Unlike Abramovitsh’s previous works, this book soars above the Jewish society it depicts.

Forget Baba Yaga, the mythical evil spirit: In the final section of the book that Abramovitsh was to expand over the next several decades, the Devil himself takes Isrolik on a flight across eastern central Europe, where mobs are attacking Jewish communities and officials and writers are disgorging rivers of ink in anti-Jewish polemics. The Devil displays the horrifying effects of the Industrial Revolution, and also of intra-Jewish rivalries. Abramovitsh had translated Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon; or, Journeys and Discoveries in Africa by Three Englishmen into Yiddish, and he adapted the perspective of that adventure story to this overview of Europe.

He had created Mendele as a narrative platform for criticism of whatever was visible at eye level in the Jewish world—socially, economically, and culturally—but here Isrolik is lifted high off the ground to reveal the surrounding landscape. The wide aerial shot from the much higher elevation provides the political context within which the action is taking place. And the Devil has a plan for Isrolik: He will drop him back down on earth so that he can ride the Mare, taking advantage of her misery and pretending always to be doing so for the common good. Lull her with soothing lullabies, put her off with false promises, and threaten her with exposure if she doesn’t obey him.

The Devil shows Isrolik how to become the kind of leader we find among minorities who exploit the weaknesses and dependencies of their constituents. When Isrolik refuses to take this advice, the Devil drops him, and Isrolik awakes from his trance. Nothing has been resolved—nothing has been improved—but at least it has been established what keeps the Jews in a state of danger.

One of my luckiest breaks in life was when my teacher Max Weinreich proposed that I begin my graduate studies in Yiddish literature with a semester-long tutorial in “all of Mendele.” Most teachers today would probably begin the study of modern Yiddish literature earlier (say, with Nachman of Bratslav), but, at the time, some teachers would not have chosen Mendele at all. They did not like the idea of studying the satire of Jews who had just been erased from the face of the earth. Did it make sense to celebrate Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh for his incisive critique of a world that was so mercilessly destroyed? By 1960 many did not think so.

The first Hebrew educators who set up the curricula for the Hebrew high schools of Tel Aviv and Haifa in the early 20th century naturally taught Mendele (as they referred to Abramovitsh) to show off the achievement of modern Hebrew fiction. But after the Shoah they no longer wanted their students to view the martyrs through this negative portrayal. Even Jacob Glatstein—the Yiddish poet who in his brilliance most resembled Abramo-vitsh—wrote a withering essay on Fishke the Lame, berating literary critics and historians who dared suggest that his beggar’s pouch was the symbol of the Jew, and taking the author to task for his heartless treatment of a destitute population.

But there are few Jewish authors as important as Abramovitsh, creator of Mendele the Book Peddler. I say this not just for his literary achievements as the founding figure of both Yiddish and Hebrew literatures, or because literary history should stay true to itself, or for many other good aesthetic, pedagogic, or national reasons, but because the work of Abramovitsh cumulatively and in some of its parts provides the most incisive analysis I know of modern Jewish politics and of politics generally. Isrolik, our would-be Jewish reformer, dramatizes the cognitive dissonance of the classic “enlightened” Jew who doesn’t want to know the Devil’s point of view, even when he is forcibly exposed to it. From Abramovitsh one learns the dangers of moral solipsism that concentrates on its own moral perfection to the exclusion of everyone else’s, and how much perspective matters in political analysis.

As the most scathing social critic Jews have ever produced, Abramovitsh came to understand the distortions of intramural satire in a polity under siege. He raised his platform of criticism up, up, up to see such corruption as a speck on the continent where the Devil holds sway.

Suggested Reading

It’s Complicated

Isaiah Berlin's influential liberalism is partly explained by his Zionism.

Ruby Sees Red

"I’m still trying to wake up from this nightmare. I walk in the streets. I see parents with babies. I can’t look. I walk in Riverside Park, I see an older man hugging his granddaughter, and I almost start crying. We have been forced back into Jewish history, into the bloody raw part of Jewish history."

Secret Chord

When the Yom Kippur War started, Leonard Cohen left the Greek island of Hydra and headed for Tel Aviv. He was coming in solidarity but he was also looking for a way to sing again.

A Sharp Word

From his intensive study of Hebrew and Jewish history to a surprisingly romantic Zionist congress in Basel, and the horrors of the Kishinev Pogrom, 1903 seems to have been a turning point for the young Jabotinsky.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In