Secret Chord

I spent the summer of 2000 traveling the battlefields of Israel, which meant road and hiking trips in the Sinai, Negev, and Golan with my friend Michael Kovner. Michael is the son of Abba and Vitka Kovner, the Zionist firebrands who led the Vilna Ghetto underground. He had been a member of Sayaret Matkal, the famed Israeli commando unit, so he knows something about war and the meaning of Jews fighting for their own nation. At the time, I had the vainglorious idea of writing a history of modern Israel patterned on War and Peace, for what has that history been if not battle after battle with moments of reprieve?

Michael agreed with this to some extent, but warily. He spoke with pride of the 1948 war and showed me where his father had been stationed—Negba, the Negev settlement where outnumbered and undersupplied kibbutzniks held up the Egyptian army for several crucial days. He showed me the ruins of the ancient Roman road in the south, which, buried by sand and discovered by overflight recon, was unearthed, fortified, and used by Israeli armor to outflank the Egyptians. He showed the base where his unit deployed during the Suez Crisis in 1956 and the compound where he’d been on standby in 1967, in a war that came and went so fast he hardly had time to gear up. But his mood changed when he led me through the battlefields of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Working security at the Israeli Consulate in New York when he first heard of Egypt and Syria’s surprise attack, Michael went straight to JFK, where hundreds of Israelis had converged from around the country to get a plane back to Tel Aviv. Michael told me about his flight, the lights of New York vanishing, darkness out the windows over the sea. To me, it seemed inspiring: all these young men, most of whom had been born before the founding of the state, returning to defend their nation, which, had it existed a generation before, might have saved millions of Jews. But that’s not how Michael saw it.

From an American point of view, Israel’s ’73 war, though brutal, looked short and decisive, ending in a victory that created the conditions for peace with Egypt. But to Israelis, who had believed they’d won so commandingly in 1967 that there’d be no more wars for at least a generation, 1973 came as a brutal awakening. One afternoon, on the holiest day of the year, every citizen suddenly realized the war might never end. It was less a circumstance than a mood, a mournful funk that settled over the country and has never really lifted.

Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai, by journalist Matti Friedman, which chronicles the singing tour Leonard Cohen made of the front during the Yom Kippur War, does more to explain this mood and why the Yom Kippur War devastated Israel in a way that is unjustified by simple numbers than any book I’ve ever read. On its surface, it’s a portrait of the Canadian-born poet and singer. In 1973, Cohen was living with his common-law wife and child in Hydra, a Greek island. He’d had a few minor hits, including “Suzanne,” “Bird on the Wire,” and “So Long, Marianne,” but he had come to an artistic impasse. “Cohen wanted a way out of his dead end,” Friedman writes. “He was looking for a way to sing again, and might have been seeking what he’d called a ‘vertical seizure,’ a revelation like one the Israelites had experienced long ago in Sinai.”

Cohen’s family was Orthodox, his grandfather had been a rabbi, and he grew up as the son of one of the most prominent families in Montreal’s Congregation Shaar Hashomayim. His best lyrics might sound like a Jew reaching out for God (“I forget to pray for the angels/and the angels forget to pray for us), but he was far from observant. And yet, when the war came, he found himself heading for Tel Aviv, just like my friend Michael and all those Israelis at JFK. He later said it had been his plan to volunteer on a kibbutz, freeing a young worker to join the fight. But this seems like a vague justification for an irresistible impulse. The simple fact is, he felt the pull, and went.

Cohen checked into a hotel when he arrived in Israel, then began hanging out in the sort of Tel Aviv cafes frequented by singers and artists, some of whom recognized him, including the great Israeli musician Matti Caspi, who had been performing at the front as part of their military service. Cohen tagged along. No records were kept of his performances. Friedman has reconstructed the tour through the memories of other performers and the soldiers who made up the audiences at bases in Israel, the Golan, and Sinai. In the last days of the war, Cohen played for small units across the Suez Canal in Egypt, a dangerous area known to soldiers simply as “Africa.”

This was no USO tour. Cohen wasn’t like Bob Hope climbing out of a Huey with a bevy of hangers-on and showgirls. He and his fellow performers lived rough, same as the soldiers. They borrowed beds for a few hours of rest, slept in tents or out in the open, under the missiles, fighter jets, and stars. To the soldiers who had never heard of Cohen—the majority—his appearance was strange and welcome. To those who had heard one of his songs on the radio, his appearance was another one of the surreal things that happened in October 1973. Everyone who saw one of these shows remembered and was changed by the experience, including Cohen. He’d been stuck. He’d stopped performing and wondered if he’d ever write again. The weeks of the war—the constant presence of danger, the camaraderie of the soldiers (“You’re all together, and you’re here for one another, and it’s so rare and touching to see it,” he told an audience), the heroism, death and fear, being in the land of Israel—opened a new channel in him. He kept a diary, recording images and phrases that he turned into lyrics. He wrote his first new song in years—“Lover Lover Lover”—in those weeks and was performing it by the end of the war. It begins:

I asked my father

I said “Father change my name

The one I’m using now it’s covered up

With fear and filth and cowardice and shame.”

His music had always had biblical undertones, but in the decades that followed, many of his best songs were almost liturgical: “Hallelujah,” “Tower of Song,” and, of course, “Who By Fire,” Cohen’s ironic but loving and utterly serious riff on the high holiday prayer Unetanneh Tokef (“And who by fire, who by water/ . . . Who by very slow decay/And who shall I say is calling?”).

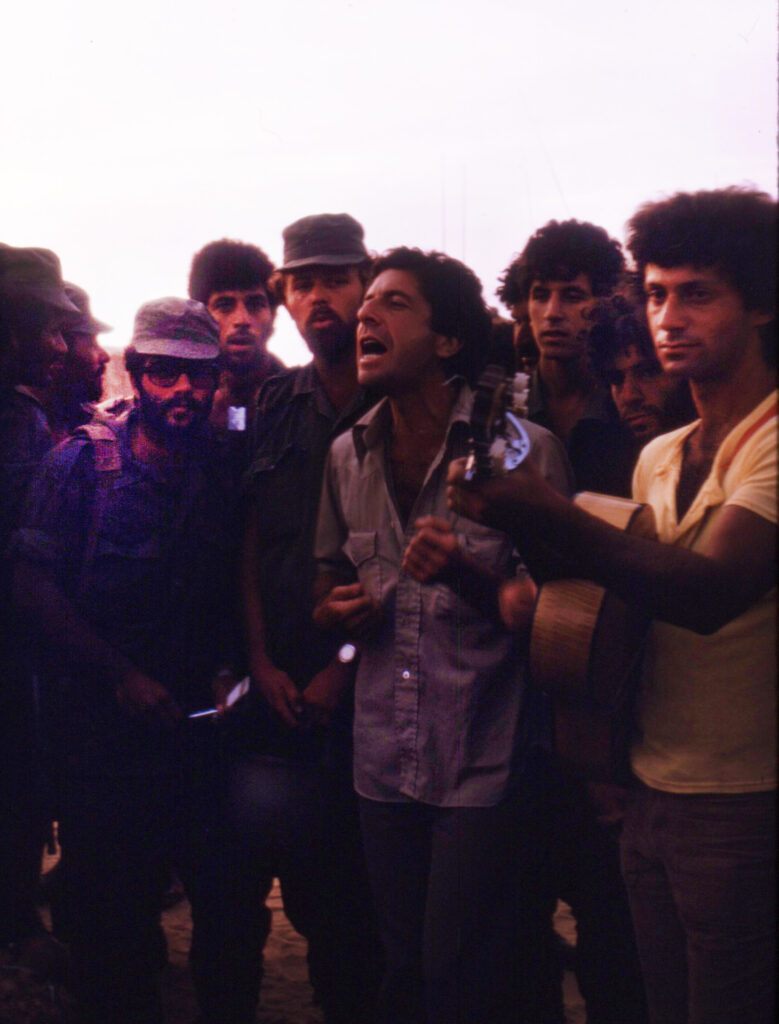

In addition to his own experience as a journalist and soldier, as well as his interviews with veterans, Friedman had access to three key sources in writing this book: Cohen’s wartime diary, the lost manuscript of an unfinished novel of the war he had tried to write, and a collection of incredibly evocative photos taken by an Israeli soldier named Isaac, who served on the bleeding edge of Sinai. Some show Cohen performing before small groups of soldiers and officers, including Ariel Sharon shortly before he defied orders, crossed the Suez Canal, and basically won the war.

Though Cohen, young and dark, playing in sandals or barefoot, is the focus of many of these images, Friedman’s book is really less about him than about the audience, the dirty unshaven grunts in fatigues, crossed-legged or on their haunches, wide-eyed, exhausted. It’s their stories that form the backbone of this beautifully melancholy book. It’s through their experiences, several of which are told in detail—how they heard, how they went; how they lived, how they died—that we come to understand why Israelis consider the short, intense Yom Kippur War as much of a turning point as the War of Independence or the Six-Day War. Cohen serves mostly as a point of focus, a ribbon running through the lives of half a dozen members of the IDF.

Cohen left Israel when the peace talks began. “As soon as the politicians are in the picture, I’m out,” he said. He hardly ever spoke of his experience in the years that followed. Part of this might have been image management. Like most Jewish artists, Cohen was looking for a big audience and didn’t want to be typecast. But most of it seems personal. If it’s important, you talk about it. If it’s very important, you don’t.

Some Jews have held this silence against Cohen—as if he was embarrassed of Israel. But to those who saw him perform at the front in 1973, or heard about the performances, this was never the case. “The fact that Israelis have always considered Cohen to be a kind of Israeli is not only because he’s Jewish,” writes Friedman. “There are plenty of Jewish artists, and almost none with that status. It is, at least in part, because of the memory that at one of this country’s darkest moments, he came.”

Suggested Reading

Like an Echo of Silence

Lea Goldberg’s poetic voice didn’t project outward; it drew the reader in, inviting intimate conversation.

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

Sharansky’s Exodus

Witnessing the modern exodus of Jews from Ethiopia to Israel—different than his own but no less stirring—reminded Sharansky of what he’d told himself in his darkest days in prison: “Your history did not begin with your birth or with the birth of the Soviet regime. You are continuing an exodus that began in Egypt. History is with you.”

Paradox or Pluralism?

Walzer’s paradox of liberation, if that is what it is, is that religion is back, or that despite the extraordinary success of secularizing revolutionaries it never quite went away.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In