To Spy Out the Land

“We won’t need to die . . . and when the day comes, the boys will turn into green crowned date palms and next to them their girls will petrify into statues of white marble,” wrote the young spy Avshalom Feinberg. While the letter’s recipient, Rivka Aaronsohn, would live until 1981, Feinberg, along with Rivka’s sister Sarah, would die violently within a few years. Some 100 years after the destruction of the Nili spy ring, to which they belonged, two new books tell their story. (Nili was a password taken from Samuel I 15:29, “Netzach Yisrael lo y’shaker,” roughly translatable as “The Eternal One of Israel does not lie.”)

Published shortly before his death, James Srodes’s Spies in Palestine: Love, Betrayal, and the Heroic Life of Sarah Aaronsohn grew out of a misfiled document the author happened across in the British National Archives while researching a biography of CIA director Allen W. Dulles. Alongside the initials of dozens of civil servants who read the document appropriating 10,000 British pounds (about $600,000 today) for an experimental agricultural site at Atlit, outside the town of Zikhron Yaakov, was a scrawled note, “Considering our moral responsibility for the unhappy fate of the ‘A Organization,’ this is the least we could do.” Like that mislaid government form, the history of the Aaronsohns and the Nili spy ring, which aided the British in their fight against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, has gone through many hands. As Srodes himself observes, “It is an important caution for the reader that not all histories, and certainly not all biographies, on this topic are in agreement. Contradictions of fact, disagreements over interpretation, and individual motives of the historians themselves can confuse.”

The more recent publication of The Woman Who Fought an Empire: Sarah Aaronsohn and Her Nili Spy Ring by Gregory J. Wallance shows how right Srodes was. The two writers disagree on matters both large and small, from the foundational question of whose influence was strongest in the spy ring to intimate matters of the heart. Almost from the beginning, Srodes and Wallance diverge: One names malaria as the cause of the high mortality rate among the early pioneers that almost doomed the settlement; the other points to dysentery. (A third book, published in 2005, to which I will return, clarifies the matter: Those early First Aliyah pioneers fell victim to both diseases.) They are most at odds about Sarah Aaronsohn’s character and love life. Srodes describes her marriage to Chaim Abraham, a Constantinople merchant who never followed her to Palestine, as one of convenience and links her romantically to fellow spies Avshalom Feinberg and Yosef Lishansky. Wallance calls her marriage loving and acknowledges an affair only with Lifshansky. He depicts her as a singularly cool-headed operative, who, unlike her excitable male colleagues, remained focused on the mission. (Both authors, however, discount the persistent speculation of a dalliance between Sarah and T. E. Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia,” based on his enigmatic dedication of Seven Pillars of Wisdom to “S.A.”)

After a brief prologue set in early 1917, when the shadow of the Great War fell fully on Zikhron Yaakov, Srodes backtracks to tell the story of the founding of the town by members of the First Aliyah, including Sarah’s father, Ephraim, and the genesis of the nearby Atlit agricultural station in the pioneering work of her world-famous agronomist brother, Aaron. In addition to Sarah and Aaron, their brother Alexander was also central to Nili. The little network of spies used their access to local Ottoman troop positions and intimate knowledge of the region to help the British war effort. In doing so, they were correctly betting on the British, but not everyone in Zikhron Yaakov or the Old Yishuv, more generally, agreed. Srodes usefully situates their actions within the context of competing national identities in the region and the global race for petroleum that focused the entire world on the Middle East.

Because Srodes starts his tale near the end of the Nili affair, readers know its terrible outcome in advance. On the eve of Sukkot, 1917, the residents of Zikhron Yaakov suffered along with 27-year-old Sarah Aaronsohn, unable to escape her screams as she was tortured by Turkish operatives. On Srodes’s telling, it was vital that she hold out because, unlike the other spies, not to speak of those friends and family members who were not part of the clandestine circle, “she alone . . . held a great secret”: British forces under General Edmund Allenby were poised to strike from Egypt with the goal of capturing Jerusalem.

Srodes, a prolific biographer whose prose tends to the florid, can hardly be blamed for his description of Sarah as a “hardened warrior,” in these circumstances. In this matter, Wallance affirms him: “The Turks were students of torture who applauded the discovery of a new method as though it was a scientific breakthrough; some had studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition to refine their skills.” The practice of beating the soles of a victim’s feet with rods or tubes, known as faluka, was one of the mildest forms of torment that was inflicted upon her. But she kept her secrets, even as she drifted in and out of consciousness, and even when her innocent relatives were tortured in front of her.

Spies in Palestine is an excellent resource, but it is hampered by Srodes’s unwillingness to trim details and dramatis personae. While it is important to know how Aaron’s American and British contacts opened doors to American benefactors and British military intelligence that would have remained closed even to a “self-taught prodigy in botany, geology, and hydrology” credited with the rediscovery of the “mother of all wheat,” Srodes’s exhaustive list of his important contacts burdens an already far-ranging narrative. Nor is he willing to truncate or elide any of Nili’s breakthroughs and accomplishments or its challenges and setbacks.

What largely rescues Srodes’s account is the drama of Sarah’s life and death itself. As Srodes weaves the tale of her last days of freedom, the lost possibilities for her escape are painful to contemplate. And there are the words she left behind. After one has read what she was subjected to, it is almost unbelievable that she was able to threaten her captors, saying, “Your end is nigh, you will fall into the pit I have dug for you.”

If Srodes is a popularizer, Wallance is more of a scholar. His carefully footnoted The Woman Who Fought an Empire draws more closely on the archival material, primarily from that of the Beit Aaronsohn Nili Museum in Zikhron Yaakov. Where Srodes declares the importance of Nili intelligence, Wallance demonstrates with specifics. Nili operatives, going about their work as doctors, farmers, and merchants, mapped the location of Turkish forces, as well as the state of their training and equipment. They also mapped the bridges, roads, and fortifications built by the Turks’ German engineers. Wallance tells us that a Turkish army engineer Sarah recruited as a spy produced a map of Jerusalem “on which he had marked the location of Turkish fortifications.” Another Nili intelligence coup described by Wallance provided both the number and capability—including flying speeds and machine gun capacities—of the airplanes that were being brought in to reinforce the Gaza–Beersheva front. That information gave the British time to move in additional planes and ensure British air superiority. Information from the Nili was so reliable, he explains, it was used to verify other sources. Ottoman ruler Djemal Pasha certainly believed Nili tipped the balance against him, railing, “All my friends warned me, don’t trust the Jews, and I treated them well. . . . See how Aaronsohn showed me his honesty and his trustworthiness. I allowed him to travel to Berlin for his alleged scientific purpose—and he escaped to the British and organized spying against me.”

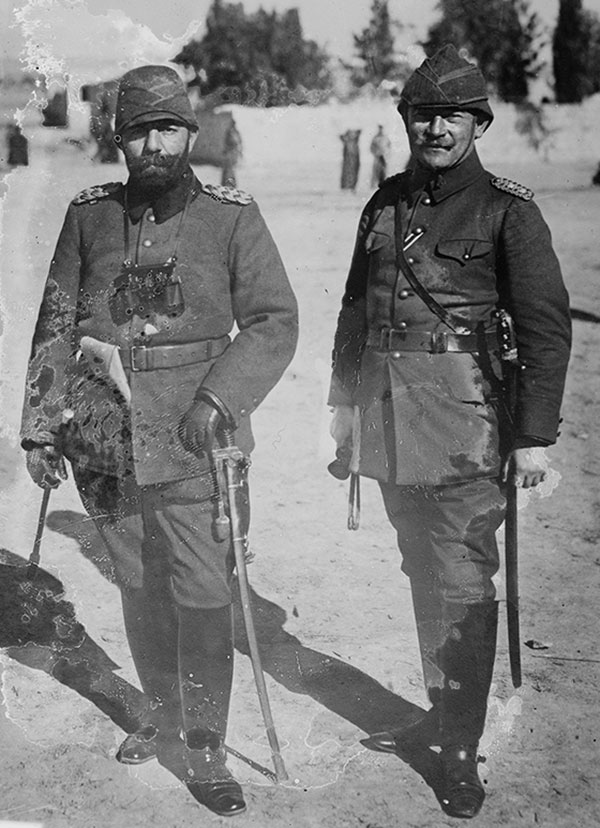

Collection, Library of Congress.)

Wallance’s narrative allows Sarah to step out of the shadow of her famous brother and her headstrong colleagues, showcasing her intense focus and sense of duty to her fellow Jews. On Wallance’s telling, Nili was not only the scientist-diplomat Aaron’s project. He describes Sarah’s horrified eyewitness reports on the Armenian genocide as just as central to Nili’s founding as Aaron, Alexander, and Avshalom’s hatching plans to aid the British for Zionist ends. Where Aaron paid bribes to and joked with Djemal Pasha, Sarah was convinced that Djemal “would match, if not exceed, the brutality of the dozens of sultans who had ruled the Ottoman Empire over six centuries.”

Although she did not, like many spies, “thirst for danger as a means of self-fulfillment,” Sarah seems to have been born for the world of clandestine operations. When she sent warnings from Constantinople to her family in the Yishuv of the massacre of the Armenians, a fate she feared would befall the Jews, she wrote in tiny handwriting covered with large postage stamps. To get the recipients to look under those stamps, “she wrote a letter to Rivka urging her to admire ‘the boule’; using the French word for tree-lined boulevard, but really a pun on the Hebrew word bul, or stamp.” It was Aaron who established contact with the British and convinced them that he was neither a double agent nor a crank, but it was Sarah who did the hands-on work of recruiting sources and reactivating those who had fallen silent. She even took risky trips to Damascus to eavesdrop on the German officers aiding the Ottoman war effort.

Unlike mercurial colleagues Avshalom Feinberg, whose rashness led to his death at the hands of Bedouins in the Sinai, or Na’aman Belkind, whose drinking habits led him to reveal the existence of Nili and the names of its members, she spent the day before her arrest burning incriminating documents. In contrast to her silence under torture, Aaron’s misgivings about using the agricultural station for espionage led him to confess the ring’s activity to his American benefactors, an admission that put everyone’s life in danger. Wallance does not mince words: Aaron’s departure from the Yishuv was for the best, “not only because his stature might finally gain the cooperation of British intelligence, but also, simply put, he was not a good spy.”

Where Aaron could be excitable and rush into decisions, Sarah was stoic. She continued to collect intelligence even when communications with—and much-needed funds from—the British failed to arrive. Frustrated with British bureaucracy in Cairo, Aaron wrote in his diary:

More than twenty times I felt like throwing up to their face what I thought of their complete and irremediable inability to understand the situation. A hundred times daily I curse the moment when we decided to work with them . . . better [to] commit suicide than to continue under such conditions with people whom we thought were our friends.

Suicide is one thing to threaten and another to do. Facing transport to Damascus where further torture and certain death awaited her, Sarah managed to convince her Turkish guards to give her a few minutes alone in Aaron’s house to change before the journey. In that time, she wrote out her final instructions to the Nili network, located a hidden gun, and shot herself.

In the early 1900s, Zikhron Yaakov was still very much a small town where rivalries and grudges grew abundantly. The Aaronsohns—people said—thought they were better than their neighbors. Aaron, in particular, drew resentment for the imperious way he directed the Atlit station and, perhaps, simply for his spectacular successes. This commonly held opinion was not helped when he convinced his younger brother Alexander to go to the United States, where Alex filed papers to become a citizen and went to work at the Department of Agriculture. Alex’s articles in The Atlantic Monthly extolling the virtues of Palestine were not relished in Zikhron Yaakov. As Srodes puts it, “Sentiment held that one Aaronsohn celebrity swanking about abroad was enough, two was too much.” Had they been more steeped in the traditions of their Romanian Jewish ancestors, the two might have given a thought to the ayin hara. As it was, they were visitors at the mansions of Secretary of State Robert Lansing, his nephews John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, and Assistant Navy Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt and hobnobbed with luminaries such as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Herbert Croly (the editor of the then-influential The New Republic), and multimillionaire Herbert Hoover.

Nor was that the only source of conflict. First Aliyah families like the Aaronsohns were scorned by Second Aliyah newcomers who wanted to work the land in place of Arab laborers and institute communal property ownership and decision-making. Second Aliyah self-defense groups like Ha-Shomer simply refused to protect First Aliyah towns such as Zikhron Yaakov and Hadera. In 1913, Alexander Aaronsohn and Avshalom Feinberg, the fiancé of Rivka Aaronsohn, formed a rival group called the Gideonites. Young men with horses and guns “joined as a brotherhood, with a sworn oath of secrecy and a pledge to match violence done to them with greater retaliation.” Their frequent and violent skirmishes with Arabs in nearby villages over destroyed crops and stolen livestock gave them confidence. Many Nili spies—including the hotheads who would play a role in the network’s discovery by the Turks—came from the ranks of the Gideonites.

Wallance points us to another book about the Nili spy ring, A Strange Death by Hillel Halkin (the death of the title is not, incidentally, Sarah Aaronsohn’s). Halkin’s 2005 book is, despite the dark subject matter, a pleasure to read, showing how small-town feuds and rivalries, past hurts, and insults intersect with historical events. Halkin underscores how, by defining a life as “historic,” historians elide much that makes a life. His Sarah is not an untouchable heroine, but rather a woman whose “heroism and passion” are “perfectly human.”

Begun after Halkin moved to Zikhron Yaakov, the writing turned him into a kind of spy, cultivating sources, digging out secrets, and surreptitiously entering deserted buildings. Halkin’s tale is full of historical rhymes, echoes between past and modern events, which afford the reader literary pleasure and historical insight that ordinary biography cannot provide.

Halkin tells us of an older book, a “thin, paperbound volume . . . barely a hundred pages long.” It was Sarah, Flame of The Nili, found in the deserted home of Tzvi Aaronsohn and signed by both Alexander and Rivka. It is a book for young readers, and Halkin dismisses it until he reaches an absolutely stunning passage:

The people of Zichron felt they would go mad if they had to hear the screams of the tortured prisoners any longer. But there were also four women who ran through the streets of the town, laughing and jeering at each scream. And though we may leave their eternal damnation to others, let it be known that each was requited in her way.

Halkin’s book was written out of an attempt to understand not Sarah’s bravery, but the laughing and jeering of such “Gorgons and Furies.”

Where Wallance and Srodes both place their trust in the established archives, Halkin shows us memorial books from small settlements, township council notes, pictures found in abandoned buildings, and the memories of those who lived through Nili and the aftermath, as malleable and unreliable as those memories might be. The established narrative is that fear of the Turks motivated those Jews who opposed Nili, even to the point of betraying it. As Wallance puts it, “The perspective of Jews in this region was that espionage was dangerous and that relations with the Turks could be managed. Why revolt against an empire when it can be bribed?” Halkin bids us to look deeper:

If you wanted to know who did what—joined the spy ring, was for it, against it, took no stand—you had to put the big things aside. The course of the war—the hopes of the Jews—the plans of the British—the right to risk lives that hadn’t asked to be risked: These were not the keys that fit the doors on [Zikhron Yaakov’s] Founders Street. To open those, you had to know other things. Who was related to whom. Who was the neighbor of whom. Who was friendly or had quarreled with whom. Who was more brave, prudent, adventurous, selfish, caring, or timid than whom.

The grave of one of the four women who was alleged to have jeered as Sarah Aaronsohn was tortured sits alone, away from her family members. Her “mitah meshunah,” her strange death, ended her life at age 50, five years after Aaronsohn’s death. Sarah’s grave is there too, not outside the cemetery proper, as is customary in the case of suicide, but next to her mother and surrounded by a fence that instead of setting her apart as shamed appears to give her a place of honor.

There had long been rumors that Yosef Lishansky and Avshalom Feinberg had not been attacked by Bedouins while attempting to cross into Egypt to reestablish communications with the British. Instead, the town gossip went, Yosef killed Avshalom in a rivalrous argument over Sarah. The falsity of this rumor “was proven after the 1967 war,” Halkin tells us, “when Feinberg’s remains were dug up by Israeli soldiers in Sinai with the help of an old Bedouin who corroborated Lishansky’s story.” Over the site grew a lone date tree.

Suggested Reading

Walking the Green Line

New books about the settlers and the settlements and depth and nuance to the discussions about their existence.

Straying from the Fold?

Are typical Jewish converts ensnared in the nets of Protestant missionaries “swindlers, thieves, drunkards, whores, schlemiels, schlemazels, nudniks, and no-goodniks”?

I Believe: A Poem

Please remember, contestants, to phrase your answer in the form of a question. —Alex Trebek, host of Jeopardy!™ I believe with a perfect faith in the coming of the messiah, though he may tarry. —Late medieval reformulation of Maimonides’ 12th Principle of Faith, Commentary to the Mishna, Sanhedrin, Perek Helek. In the days of the Messiah, each individual will…

Cognitive Dissonance

Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future. His proposal may surprise you.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In