Michael Chabon’s Sacred and Profane Cliché Machine

In the institution’s most controversial graduation ceremony since the infamous “Trefa Banquet” in 1883, Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Michael Chabon took the podium at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Los Angeles and exhorted his audience to “knock down the walls.” This meant, first and foremost, Israeli security checkpoints and barriers, but by the end of the talk, Chabon had extended his demolition to-do list for these future rabbis and Jewish communal professionals to seemingly all rituals and expressions of Jewish difference, and perhaps—he wasn’t quite sure—Judaism itself.

No doubt, HUC expected an edgy talk from Chabon. After all, he and his wife, fellow novelist Ayelet Waldman, recently teamed up with the far-left Israeli NGO Breaking the Silence to lead a group of writers to the West Bank, then published a book of their essays, many of which can be fairly described as gullible anti-Israel agitprop. In the inevitable damage-control statement afterward, Interim President David Ellenson and Dean Joshua Holo described the institution as an “energetic, fearless marketplace of ideas,” but they clearly weren’t quite expecting this. Nor is a commencement ceremony really the time for energetic debate. Indeed, an Israeli woman named Morin Zaray, who was celebrating her completion of an MBA in nonprofit management, appears to have been the only one who demonstratively objected to Chabon’s speech:

As I heard Chabon’s simplified takedown of my country, the room began to spin. I turned back to look at my brother, who served in a combat unit in the Israel Defense Forces. He looked sick to his stomach. I got up from my seat and approached my family. . . . I felt ashamed for being part of this gathering, ashamed that many in the audience were just nodding at this reductionist view of a multilayered and complicated country. . . . Standing outside, I was nearly brought to tears as I heard the crowd of Jews give Chabon a thunderous applause.

Watching or reading the address as published in Tablet Magazine makes it clear that his argument was not only political. Chabon took special aim at Jewish divisions and distinctions—between the sacred and the profane, the clean and unclean, and especially between Jew and Gentile. “An endogamous marriage,” he said, “is a ghetto of two,” so he no longer hopes that his children will marry Jews. Nor does he any longer find value in the many Jewish practices he mentioned from the Passover Seder to community eruvin.

As Sylvia Barack Fishman, Steven M. Cohen, and Jack Wertheimer wrote, it is tempting to ignore this all as “performance art of a personal psychodrama in a public setting,” but “Chabon’s ideas have cachet, especially in culturally and political progressive bubbles,” and these ideas undermine the viability of American Jewish life. Fishman, Cohen, and Wertheimer focused on Chabon’s indifference to, if not promotion of, intermarriage, particularly to this audience. As they noted, “only one-fifth of recently marrying Jews raised in Reform families married other Jews,” and “only 8% of the grandchildren of the intermarried are being raised in the Jewish religion.

The problem with Chabon’s ideas is more than demographic. His discomfort with Israel’s security barriers and Jewish marriage are really specific applications of a desire to erase anything that distinguishes one group from another:

I abhor homogeneity and insularity, exclusion and segregation, the redlining of neighborhoods, the erection of border walls and separation barriers. I am for mongrels and hybrids and creoles, for syncretism and confluence, for jazz and Afrobeat and Thai surf music, for integrated neighborhoods and open borders and the preposterous history of Barack Obama. I am for the hodgepodge cuisines of seaports and crossroads, for sampling and mashups, pastiche and collage. I am for ambiguity, ambivalence, fluidity, muddle, complexity, diversity, creative balagan.

This is the theme that binds Chabon’s entire address, and he riffs on it in virtually every paragraph. Interweaving his own Jewish journey with historical musings, he reaches the conclusion that Judaism has survived because of its willingness to erase “old lines and boundaries” and reinvent itself, its “opening our minds to the ideas, and our ears to the music, and our mouths to the languages, and our bellies to the kitchen-wisdom of the people living on the other side of whatever boundary line we chose, in our collective wisdom, to ignore.” Or, as Chabon’s character Archy Stallings says in Telegraph Avenue, “Creole . . . means you stop drawing those lines. It means Africa and Europe cooked up in the same skillet.”

In his commencement speech this exilic hybridity is where it’s at, though Chabon doesn’t worry much about what being “cooked up in the same skillet” meant historically for Jews (or Creoles). When he describes sitting at the Seder table thinking about how Judaism has changed and how it must change again, he thinks of “when the great Temple rose in Jerusalem, when it was destroyed and our history became a history of exile,” but our return to the land goes unmentioned. In The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Chabon’s character Meyer Landsman says:

I don’t care what supposedly got promised to some sandal-wearing idiot whose claim to fame is that he was ready to cut his own son’s throat for the sake of a hare-brained idea. . . . My homeland is in my hat. It’s in my ex-wife’s tote bag.

As the late literary critic D. G. Myers wrote, “in this view Zionism represents a betrayal of Jewish history and exile is the proper Jewish condition.” Chabon’s problem with the State of Israel goes well beyond his critique of certain state policies and settler communities. Any particular nation (but especially the Jews), any particular religion (but especially Judaism), anything that makes us uniquely us is an enduring source of shame. Chabon would rather be part of, and rather his children marry into, “the tribe that sees nations and borders as antiquated canards.”

A mishnah in Bava Batra describes two neighbors, a beekeeper and mustard farmer, who must keep the bees and plants away from one another. Honey mustard is a great flavor, but if you turn the bees loose on the mustard plant you ruin both, because they have to develop independently with their own integrity. Chabon forgets that “mashups, pastiche and collage” require difference. Hybridity is not merely about the amount of common genetic material of sexual partners. Homogeneity and heterogeneity are not literally about genetic haplotypes but are metaphors for considering sameness and difference.

Consequently, Chabon’s paean to mongrels and hybrids does not make note of something to which the Jewish tradition, with all its attention to differences, devotes a veritable library: There are different kinds of mixtures. The core of the rabbinic curriculum is all about ascertaining which ingredients retain their identities in mixtures—by imparting flavor, by stabilizing the whole, or because of their intrinsic significance—and which are batel, null, deemed to no longer exist.

This body of learning pertains first and foremost to milk and meat and pots and pans, but it is predicated on underlying ideas about individual and group identity: How does a small minority retain its identity when mixed with an overwhelming majority? How do different ingredients absorb and impart flavor to the whole? When does a mixture cease to be the sum of its ingredients and become a new entity?

Chabon expresses discomfort with “monocultural places” with “one language, one religion,” but the application of these words to Judaism is simply astonishing. Virtually every Jewish community in history has developed its own dialect. There are five Judeo-Arabic dialects alone. There is a dizzying variety of Jewish culture and multiform expressions of Jewish religiosity. Chabon, however, has no access to this amazing, diversity because he speaks no Jewish language. One is reminded of Edelshtein’s complaint about American Jewish writers in Cynthia Ozick’s classic story “Envy; or Yiddish in America”:

You have to KNOW SOMETHING! At least the difference between a rav and a rebbeh! . . . Their Yiddish! One word here, one word there. Shikseh on one page, putz on the other, and that’s the whole vocabulary!

Chabon writes “I ply my craft in English, that most magnificent of creoles,” as if speaking English, with all its layers and loan words, makes one multilingual all by itself. Perhaps sensing this, he adds: “my personal house of language is haunted by the dybbuk of Yiddish.” Alas, it is a small dybbuk (the one Edelshtein noticed) and not very frightening—or knowledgeable.

Consequently, even as Chabon celebrates even the most superficial cross-cultural fusion, the Judaism he describes is suburban, third-generation American Judaism, a monolingual, monocultural, monochromatic (but not necessarily monotheistic) sliver of the totality of Jewish experience.

Chabon singles out the Shabbat eruv for ridicule three times in his speech. For him, an eruv is just another boundary, another way for Jews to mark who is in and who is out. But the word literally means “mixture” or “combination.” The legal theory behind it is that many different private and semiprivate domains can be combined into a single household so that one can carry things from one to another on Shabbat. Creating an eruv involves negotiation with all those, including non-Jews and nonobservant Jews, who share that space. The “walls” of the eruv are, in fact, generally not walls at all. They are comprised only of posts and wires, on the premise that two posts with a lintel form a doorway. The eruv circumscribes a community with walls that are entirely doors.

Shouldn’t this be exactly what Chabon wants? Doesn’t an eruv demonstrate that a Jewish enclave can be open and permeable in either direction? The very idea of a wall made of doors undermines Chabon’s dichotomies. It reflects a different sort of boundary-making, one that is inclusive and open to mixing and merging and combining. Alas, “You have to KNOW SOMETHING!” Instead, all Chabon sees, all he wants to see, is that the eruv divides the inside from the outside and is therefore abhorrent; living in an eruv and living in Hebron—it’s all the same. No need to make distinctions.

Hebron, a small and heavily fortified Jewish community with a violent history, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, exemplifies for Chabon, all that is wrong with particularist Judaism. This, for him, is the reductio ad absurdum of Judaism’s “giant interlocking system of distinctions and divisions,”—between Jew and non-Jew, man and woman, kosher and treif, pure and impure. In fact, though he doesn’t mention it, it was in Hebron that the “sandal-wearing idiot” Abraham was commanded to mark his particularism—his particular mission, his particular covenant with God—on his body.

In one very important respect, though, Chabon makes an important point that some of his critics fail to acknowledge. He writes: “Any religion that relies on compulsory endogamy to survive has, in my view, ceased to make the case for its continued validity in the everyday lives of human beings.” He is absolutely right. Ideally, Jewish marriages should arise out of the love between two people who speak a common Jewish language, celebrate and mourn according to the same calendrical rhythm, and participate in a shared culture. Judaism survives thanks to the depth, beauty, and complexity of its traditions, not because of hysterical demands for in-marriage between indifferent Jews. Once Judaism has been watered down and thinned out, policing the boundaries of the community can only go so far.

The challenge facing American Judaism is not Chabon’s challenge, to choose openness and hybridity over closed religious borders, but it isn’t really choosing distinctiveness over assimilation either. The challenge is closer to Edelshtein’s: We must choose knowledge over ignorance. The result will be a creative, confident Judaism that is not afraid of encountering and absorbing from other cultures and is willing to influence them in turn—a robust Jewish community surrounded by walls that are doors.

Joshua Halo, dean of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, responded to Elli Fischer’s comments here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Spy’s Life

Sylvia Rafael: The Life and Death of a Mossad Spy opens not with an intrepid secret agent about to pull off a bold maneuver, as books with such titles usually do, but with nine men gathered around a table in 1977, studying a picture of an Israeli agent.

Strange, I’ve Seen that Face Before

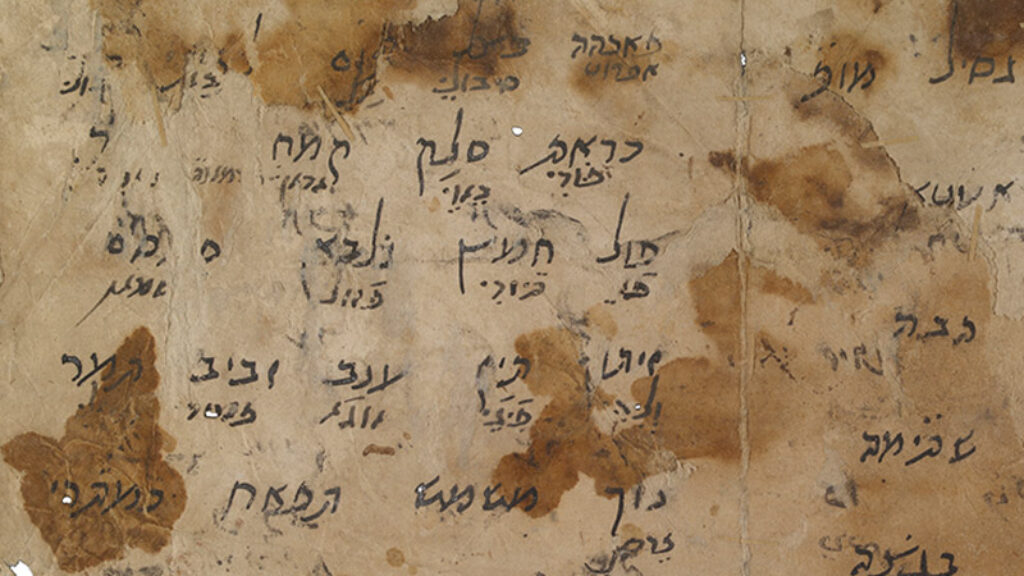

Just as I was about to close the window and move on to the next Geniza fragment, two words winked at me as if I were a friend.

Boundaries, Conversations, and the Reform Movement: A Response to Elli Fischer

Hebrew Union College dean Joshua Holo weighs in on Michael Chabon’s controversial commencement address.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

Arthur Taub MD PhD

Chabon does not seem to grasp his utter conventionality. He is a rather typical fatuously inflated poseur; in a word, a true am-ha'aretz. He does not grasp that his concept of diversity is, in fact, coerced homogeneity. He resents being Jewish. Feh!

dennis.karpf

I suggest Chabon’s ideas are not just anti-Judaism. His ideas are totalitarian. Chabon wants elimination of difference, an elimination of identity and individual conscience and enforced uniformity of free religious expression and free belief. These ideas are not just fatuous or inane. The fact these ideas are spoken at commencement of a Jewish Seminary or Yeshiva is insane.

Luftmentsch

Excellent essay and comments. I would add: once Judaism - and every other culture - has become a blanded out, grey mush with a bit of everything in general and a lot of nothing in particular, what exactly would they have to offer other cultures in this great inter-cultural exchange? How does the self-destruction of Judaism (and, presumably, every other minority culture in the world) allow anyone else to encounter, and benefit from encountering, Judaism? Chabon's "Judaism" is a taker, not a giver, by definition.

Rabbi Lord Sacks was closer to the mark when he said that if we have nothing in common, we can't communicate, but if we have no differences, we have nothing worth saying. Chabon's view of the future is a world where no one has anything worth saying, because the only thoughts anyone can think are the same as everyone else's. From that point of view, Chabon's lack of imagination and originality are hardly surprising.

watchstop

For one thing, Michael Chabon is a special, superb writer who needs counsel and coaching to speak before an audience, especially when his text is on flimsy sheets of paper and his only choice was to look deeply down at them on an insanely designed lectern. He does come across awfully terribly in the "video" of his talk. His friends should have it removed from the Internet. And thrown away, burned, torn to bits. The written text IS RICH AND FINE.

For the second thing, I think there is a formal name, though not a friendly one, for the sort of commentary (no pun or allusion to a certain other periodical is intended here) which is demonstrated now in the Jewish Review, taking up portions of his text in order to rip into his theories and ideas and ways of expressing himself. The rabbi above comes across to me as a person I want to avoid. Oh my. (I was married by a rabbi to my non-Jewish wife/bride/sweetheart of all these 54 years, going on 55.)

Meantime, I am an 84-year-old man, born to two Jews in Denver, and Michael Chabon sure as hell knows what he is talking about. For myself, on now to "Kingdom of Olive and Ash."

pmchai

I've been following Chabon's speech ever since an email went out to California Reform rabbis (which I am not-Reform rabbi, yes, from CA no). I've read the speech and watched the video. I've read much of the commentary, and I've come to the following conclusion: Intelligent people want to take this talk seriously because a) it was written by a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who has a good way with a word; and b) it was delivered at a distinguished moment in the year of one of our major rabbinical schools. So, of course, we should take Chabon seriously.

But the speech betrays remarkable ignorance. He mentions, e.g., mikvehs, married women shaving their heads on the evening after their marriage, of eruvim as examples of Jewish boundaries that we ought to cast off. These rituals point toward a Judaism—Orthodoxy--utterly foreign to his audience. It’s as though he’s been invited by an unhinged Satmar and it’s the Satmars he’s addressing, not a group of Reform rabbis and professionals who don’t give a hoot about the bride’s shaved head and consequent wig or of eruvim, and whose use of the mikveh is highly selective.

His best gaffe is toward the end. "What would happen to Judaism if all, or even most, of the world’s Jews married out of Judaism? Judaism might disappear from the face of the Earth, forever! I don’t believe that’s ever going to happen...” Well, anyone who knows his or her contemporary American Jewish sociology knows that, factoring out the Orthodox community, he already has his wish with a 70% intermarriage rate.

In the end, I suspect the folks at HUC-JIR have licked their wounds over this egregious error and likely adjusted the policy as to how graduation speakers are invited so as not to repeat this embarrassment.

jerome.hoffman

I applaud the knowledge Rabbi Fischer but what he misses is the arrogance of Michael Chabon. Perhaps he has a place in distilled American literature, but quite frankly, i have had difficulty staying with his novels because at best they are mundane. No one but an am haaretz would have the audacity to give a commencement speech to an audience far more learned than him and to display his ignorance. Sadly, he is not unique in our current culture, from the occupant of the White House to the arrogant men who have dominated much of mass media and who are shocked when they are brought to the bar of justice as harassing sexual predators.

mangold1

Let’s face it, inviting Chabon was a mistake by some well meaning Reform leaders. Chabon’s prescription for what ails Judaism, is for Judaism to disappear. Inviting him to come at another time to a forum, along with another contrasting presentation that would favor the continuation of Judaism, would have been appropriate. But to give him a platform to spew his venom at his Bar Mitzvah level knowledge of Jewish existence insults most other twelve year old Jews. I don’t believe Chabon would propose that other cultures, or beliefs, like Native Americans, or any aboriginal peoples, give up that which gives them their distinctiveness. Isn’t learning to live together while retaining that which gives us meaning, the mature adult goal? Given Chabon’s ignorance, even hatred of Judaism, religion, culture, societal organization, value of traditions and the aim to get people with differences to live together, his only value was to show us the frightening condition, that he is one of some others that we have failed. Then again maybe someone filled with such anger and hatred, may be afflicted with problems much better left to professionals.

The Chabon Problem is far greater than described by Rabbi Fischer. It’s more than an eruv, a mikve, milk and meat, a sheitel, or any other Jewish ritual. Within Judaism, going back to our beginnings, there has been a myriad of differences, even in the traditional Jewish communities. In the Talmud (b.Hullin 113a, 116a) they tell of a major difference between the Babylonian custom that chicken is to be considered meat, and may not be eaten with milk, and the custom in Eretz Yisrael where the respected Mishnaic period Rabbi, Yosei the Galilean did not consider chicken to be meat, and he ate it with milk. Ultimately the Babylonian custom prevailed. But even today, within a mile of each other there can be differences. An argument could be made that this is why Judaism survived, precisely because of the differences.

Chabon is angry about something, but it’s not about what he listed. He decided, without any training or preparation, that he is going tell the world how everything is wrong, and he knows what Judaism and the world needs to change. He is the Donald Trump of Judaism. No knowledge but with all the answers. May we be protected from the Jewish Anarchists of our day.

Rabbi Manuel Gold

stevefrankdc

Chabon should no longer be taken seriously on matters related to Judaism or Israel. He is a fake Jew: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/fake-jews_us_59623143e4b0cf3c8e8d5970