Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that might be better (or at any rate differently) discussed by someone further removed from the events it reconstructs and the time in which it took place, someone who never met any of the people who had the misfortune to be affected by these events. It begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942. The file had obviously been misplaced, for it was in the middle of his patients’ records. The letter writer was not a patient but a young doctor named Valy (Scheftel) from his native Vienna. They had been lovers. He had the good fortune to escape just in time; she was caught in the deadly trap.

Wildman, a highly accomplished journalist, wanted to find out everything she could about Valy. How did she take the separation? Could anything have been done to bring her to America? Why did Karl answer Valy’s letters so infrequently? Even the vocabulary raised questions. What exactly was a “certificate”? What did “Chamada” mean and who was Paltreu? Why did the possession of $150 make the difference between life and death in a case like Valy’s? (It was the price of a visa for Chile.) Answers to the other questions can be found in the very last Jewish book published in Germany a week before Kristallnacht: the Philo Handbook for Jewish Emigration. A primer in misery, it explained that no one wanted immigrants, especially Jewish immigrants from Central Europe. The book was reprinted in 1998, as a curiosity, no doubt.

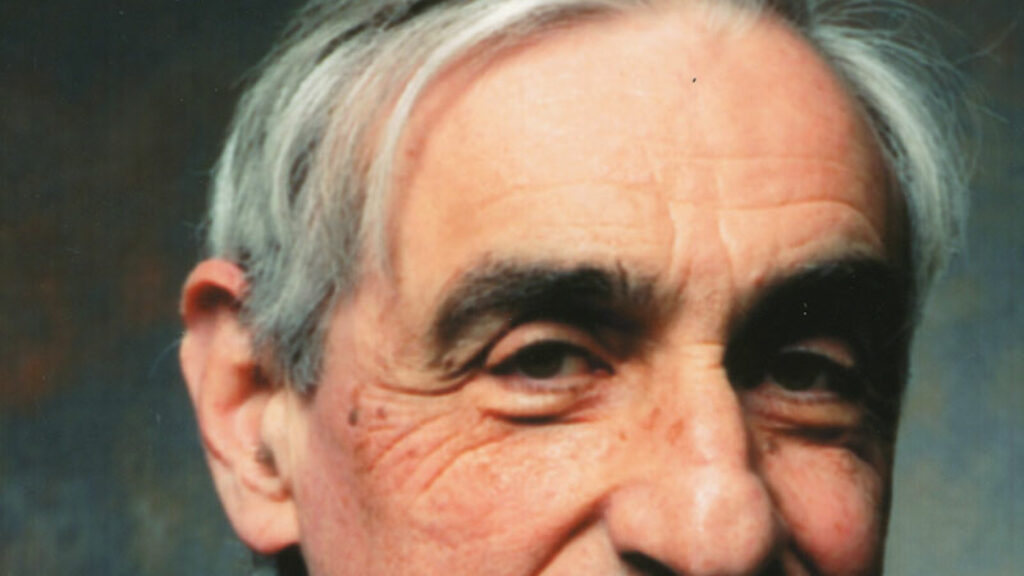

I was a witness not exactly to what Sarah Wildman relates, but to some of the events that preceded her story, and I am one of the very few still alive who knew some of those who figure in it. I may be forgiven therefore for beginning with my own recollections, which go back a long time. They do not concern Karl or Valy but a boy of my acquaintance named Hans Fabisch. I remember visiting this classmate on an afternoon in the late 1920s, in our hometown of Breslau (at that time a German city, and now Wrocław in Poland). We were exactly the same age but I was a year ahead in school, having skipped a grade. It was mainly good luck: I did not like school at that age and for this reason worked hard to get it behind me. In the end, this saved my life, for I graduated a year before the outbreak of the war and was compelled to make an immediate decision about my future. And this meant leaving Germany as quickly as possible.

Hans and I belonged to the same Jewish youth organization, whose local branch was divided into two groups. He belonged to one, I to another, and there was a friendly rivalry between us. Everyone had a nickname. Being short of stature, his was Zwerg (dwarf). But there was nothing derisive in this. He was not that tiny and was in fact rather popular, a very lively, nice boy, pleasant to talk to and to work with. The movement to which we belonged was more German than Jewish, but this was true for much of German Jewry at the time. This organization was not political; we were far more interested in camping and hiking than in intellectual, let alone spiritual, preoccupations. With Hitler’s rise to power, things began to change. Some of us became Zionists; others discovered their religious identity. One member of Hans’ family, a few years older, joined the Communists and went with several others to the Soviet Union. He seemed not to have been aware that a “purge” was in progress in Moscow. After a short time he was arrested and returned to Nazi Germany, in fact handed over to the Gestapo. (One of Martin Buber’s daughters-in-law, Margarete Buber-Neumann belonged to this group.)

The head of Hans’ group was a medical student nicknamed “Stork,” who in later life became a surgeon in New York. Stork’s father, also a physician, was one of the very few Breslau Jewish survivors. He was head of the local Jewish hospital, and it had been Gestapo policy to liquidate Jewish hospitals last. Had this very German Jew lived a few more decades he would have been surprised to learn that one of his granddaughters was to become the biographer of Isaac Bashevis Singer while another would marry a young man from Yemen.

In winter Hans’ group and mine went skiing just on the other side of the border with Czechoslovakia. We rented the hayloft belonging to a local peasant; to this day I wonder how we survived the icy nights. Recently, I received a call from members of the U.S. skiing association. It had come to their knowledge that we had been helping people who were in political trouble in Nazi Germany to escape the Reich by evading border controls. Was it true? It was true, up to a point. As groups we were not involved; we were too young to engage in political militancy. But individuals among us did assist in such escapes, and I remember one girl who paid with her life for this.

I do not recall when I last saw Hans Fabisch. In the years that followed, during the war and after, I met many members of his group in various parts of the world, often unexpectedly. But there was no word from or about him. I met his older sister, Ilse Meyer, who lived not far from our apartment in North London. She was married to “Yogi” (yet another nickname, yet another man with a variety of achievements to his credit) who had been the overall head of the youth movement mentioned earlier on. (It was banned by the Gestapo as early as 1934.) But she knew little about her brother’s last year beyond the fact that he had not survived. She knew that before the war he had trained as an agriculturist together with a group of young people on a farm near Breslau but had switched over to a school where he could study chemistry. After that, there had been occasional letters from Berlin, which had to be carefully worded because they were sent by way of neutral countries and subject to careful censorship in more than one country. She had no information at all about his last months or the date, place, and circumstances of his death.

Eventually, however, the mystery was cleared up. Following the publication of my book Generation Exodus in 2001, which told the story of young people from the German-speaking communities of Central Europe who fled from the Nazis, many survivors of this generation contacted me. One of them was Ernest Fontheim, a senior researcher in space science at the University of Michigan. He related to me in considerable detail events as he witnessed them in wartime Berlin. I put him in touch with Ilse, who found out from him what had happened to her brother. It was from a letter that he wrote to her that Sarah Wildman learned the details concerning Hans’ marriage to Valy.

From the letters she found in her grandfather’s files, Wildman knew that Valy had returned, after the German annexation of Austria in March 1938, to her home in Troppau, Czechoslovakia, both to escape the Nazis and to take care of her mother. But Hitler’s seizure of the “Sudetenland” at the end of 1938 made life impossible for the Jews there. To break loose from the “stifling, virulent, small-town racism” that surrounded them, Valy and her mother headed for—of all places—Berlin, where there was at least the prospect of employment. They settled in Babelsberg, a suburb of Berlin (and the center of the German film industry) where Valy got a job in a Jewish children’s home and hospital. Since Jews were almost completely barred from the practice of medicine, she worked as a nurse except when one of the non-Jewish doctors went on holiday or fell ill.

The letters Valy wrote to Karl make painful reading. She was very much in love and hoped that the separation would be of short duration. She had expected that he would do everything possible to help her to join him in the United States. It was this love that kept her going. There were periods of depression, and they became more frequent as time went by. But she tried to keep up a brave front. She was “dreadfully lonesome,” she wrote in one of her letters and reported the purchase of a flute. She practiced as frequently as she could, so that she would be a more accomplished player when the two of them were again reunited.

Her letters were more than just affectionate; it was “my beloved only one” and “I consider myself as belonging to you wholly and entirely and I am bound to you.” She lived in the past and the future, because the present was horrible. She wrote about how they had enjoyed the forests and the lakes in Austria, the Friday evenings at his mother’s, about trips to Dalmatia and Italy, the Viennese medical students ball: “And thus I constantly dream of how things will be when I am with you again my darling and how incredibly happy I shall be.” “In such moments I let our entire life together pass in front of my inner eyes and live through all the different phases of our life together.” And in January 1941: “Dearest, how much I had wished to be with you finally on this birthday of yours. Darling, I want so badly to say to you how I wish you all the best from the bottom of my heart. I yearn to tell you finally everything that is written only on paper, so dead, so empty and so boring. How I wish I could see you, behold your dear face.” And so she went on week after week.

But for long periods there was no reply from Karl. What had happened? Had he deserted or forgotten her? October 1941:

Beloved, I knew that I could believe in you. Once, many years ago we were walking through the Prater, it was in October and you recited the Oktoberlied [a poem by Theodor Storm] for me, about the overcast day which we wanted to make golden. We were happy then or at least I was. With you I never was quite sure how things were. This morning when I saw the overcast ugly utterly depressing day I thought in my despair that I should gild it. And just a few hours later your letter arrived and made this day golden as ever a day turned golden.

But the end of Valy’s last golden days was approaching.

There is the draft of a letter by Karl dated October 1941 in which he tries to explain why he did not answer her “sacred” letters. The only explanation he could provide for his silence was that he belonged to a generation that had been destroyed by war even if it had escaped its cannons. “I am dead because I have died mentally and morally. I cannot remember having laughed even once during the past three years.”

It would be wrong to dismiss these words as a clever but cheap way to explain his inexcusable behavior. But it was at best only part of the truth. His mental and moral death did not prevent him becoming, by his own account, a successful doctor with two practices. Nor did the fact that he had many worries prevent him having affairs with other women and getting married not long after having written this draft.

The true explanation seems to be threefold. His attachment to Valy, while probably deep at the beginning, was no longer as intense and lasting as hers. And her feeling (mentioned earlier on) “that with you I never knew” was probably right. What was by that time their three-year separation could only have been a severe trial; many, perhaps most, unmarried couples in such a situation would have drifted apart. He probably felt guilty, but how much love was left? And last and probably decisively: He was not, and could not, be aware that the issue at stake—her leaving Germany—was not a matter of love or gradual estrangement but of life and death. In the same letter, he wrote “darling I have not neglected anything regarding your immigration.” He was in debt at the time, perhaps heavily, and his ability to help her was quite limited. He could not even help to contribute to the very meager sum that might have enabled Valy, at one point in 1940, to escape to Cuba. Moral imbeciles like Breckinridge Long at the State Department who were bitterly, emotionally opposed to the immigration of even a few Jews made it exceedingly difficult for people like Valy, if not impossible. In all probability Karl would have failed even if he had tried his utmost.

Karl did not destroy the letters, but it is unlikely that he read them very often after the war. It would have been only human if he suppressed the memory of Valy. Even with all the extenuating circumstances, he must have lived with a very bad conscience.

The last letter from Valy was dated November 17, 1941. To learn her subsequent fate Wildman went to the archives in Arlosen, Germany, of the International Tracing Service, originally assembled for the sole purpose of helping governments and survivors trace the path of the Nazis’ victims but now, finally, open to outside researchers. What these files revealed was sketchy, but she now knew, at least, that Valy had survived in Berlin until she was deported to Auschwitz on January 29, 1943. And she also found out that at that time she had a husband, a man 10 years her junior and born in Breslau—my friend Hans Fabisch.

In the files there was also something that gave Wildman a shock. Someone else had asked about Valy, more than 50 years earlier, and it hadn’t been her grandfather Karl. In 1956, Ilse, Hans Fabisch’s sister, had made an inquiry about her brother and his wife. But rather than trying to locate this woman, whose last known address was in London and who, if she were still alive, would have been in her nineties, Wildman first retraced Valy’s footsteps in Vienna, Berlin, and Czechoslovakia. Eventually she placed an ad in a British publication, the Journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees, announcing that she was “looking for descendants of Ilse Charlotte Mayer.” Within two months, one of them showed up: her youngest daughter, Carol Levene. She supplied Wildman with a seven-page letter that Ernest Fontheim had written to her deceased mother after talking to me, the document that became her “key to understanding everything that happened after my letters end.”

Ernest (as I shall call him, since we became friends over the years) described Hans as his best friend during the 21 months they had known each other in wartime Berlin. He could not report how Hans and Valy first met, though it was probably at the institution in Babelsberg where Valy worked and where Hans had also found employment. Hans at that time, he says, remained a great optimist: The war would end one day and he would become a medical doctor, not of course in Germany. He was studying medical textbooks and Valy offered to coach him. The two became a couple and moved into a little apartment in one of the “Jew houses,” the new ghettoes.

At the end of 1942, however, the Babelsberg children’s institute was on the verge of closing, which meant that Valy would be deported. Hans, for his part, was safe, at least for the time being, since he had in the meantime moved to Siemens, where he was doing work that was of some importance for the war effort. Hans offered to marry Valy so as to exempt her from deportation. Valy seems to have been a little reluctant at the beginning. She was, after all, 10 years older than Hans. But she had also at long last given up any hope as far as Karl was concerned. They married on January 5, 1943. Was it a marriage of convenience? Ernest, who knew them best, says that practical reasons were of course involved, but that they were also deeply in love.

What did deportation mean? Hard labor under bad conditions in Eastern Europe—or something much worse? By mid-1942 matters became much clearer. It was a trip from which no one ever returned, nor were there any letters or other signs of life. In brief, it meant death even if it was not yet clear by what means. Ernest, Fabisch, Valy, and their circle of friends among Siemens workers did what they could to hang on, but they also discussed means of escaping a fate that seemed more inevitable by the week. They managed to buy or fabricate false identity papers. But more than forged identity papers were needed. One had to obtain money and above all contacts with local people willing to help, and this was not easy for those like Valy and Hans who were not native Berliners.

In the end, psychology was the decisive factor, and, of course, accident also played a central role. As one contemporary put it: Pessimists stood a better chance of survival than optimists for they expected the worst and were inclined to go into hiding immediately. Hans was an optimist almost to the end. He and Valy waited too long.

On January 18, 1943, when he learned that deportation vans were on Hans and Valy’s block, Ernest did his best to warn them, but he wasn’t successful. The details of his attempts and failure would be better related in a film noir than in cold prose. Hans Fabisch died, probably by suicide, two weeks after his arrival in Auschwitz; the date of Valy’s death is not known. Their married life together had lasted less than two weeks.

Ernest himself survived the next 30 months in a garden allotment in a distant Berlin suburb. He was almost caught at the very end, but good luck for once did not desert him. This is yet another amazing story which should be told one day. After the war he went to the United States where he finally received the higher education he craved and enjoyed his successful career.

The dreadful events described in this book will not come as a shock or total surprise to the few surviving members of my generation. I have witnessed similar situations in my own life and that of my contemporaries: fear, the panic of being trapped, relief at being saved owing to accident, love in the shadow of death, sacrifice and betrayal, and guilt for not having done all that one could have done to save a person close to him.

For someone like Sarah Wildman, who enjoyed what is now termed die Gnade der späten Geburt (the good fortune of being born too late), the telling of the story of Karl, Valy, and Hans Fabisch involved more than an enormous amount of research in several countries and various languages, interviewing both experts and contemporaries of Karl and Valy, persuading them to open up. It also required a measure of empathy seldom displayed by writers dealing with a period so different from their own. I thought it could not be done and half-tried to persuade her (as she relates) not to undertake the effort.

I am glad she ignored my advice. For by telling the story of three individuals from among the millions who were exiled or slaughtered she has made a major contribution towards the understanding of this whole tragic period in recent history.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Intense Listening: The Poetry of Harvey Shapiro

Harvey Shapiro, who grew up in an observant Jewish family, was a connoisseur of distances and silences.

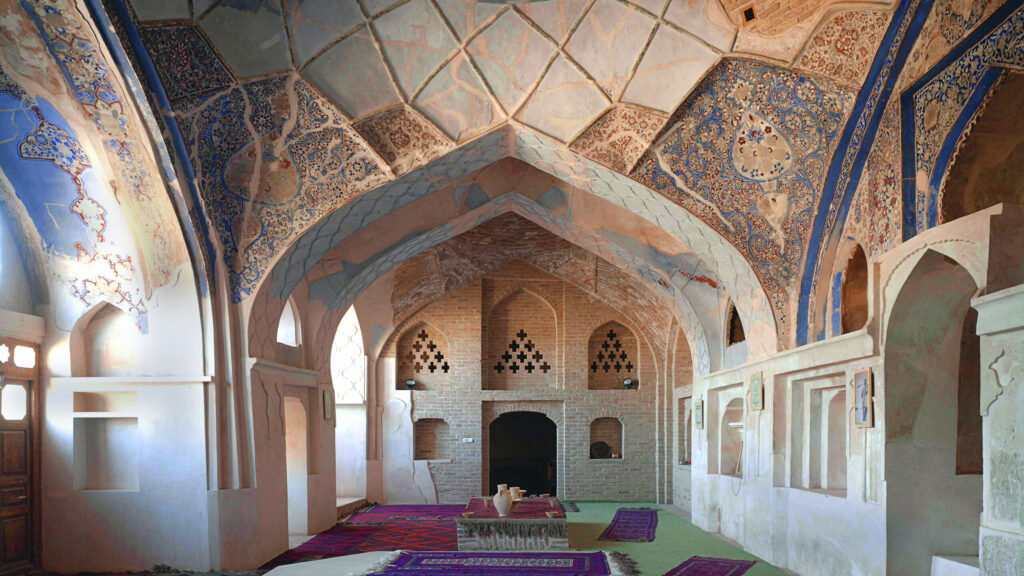

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Tradition and Invention

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled.

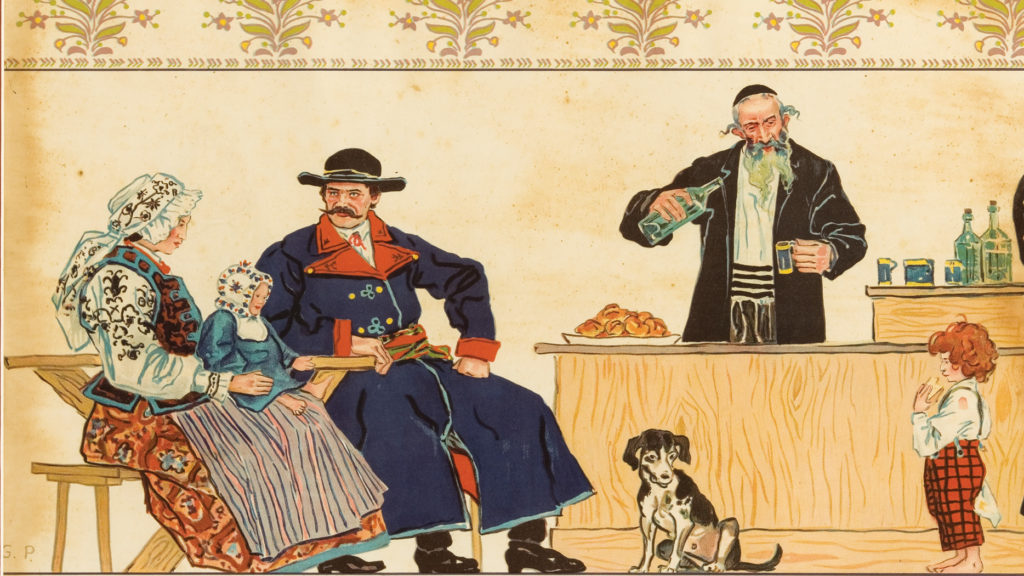

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

dorothee.lk

What a coincidence to find this extended review of a book which also had hit me by surprise. Someone had given me a personal summary from which I gathered that one of the protagonists, Hans Fabisch, could have been my old friend Yogi Mayer’s brother-in-law. Yogi had been visiting me in the town of his youth since 1988; when in London I also met Ilse – it took a long time to befriend her.

But at last we spend some time on the Rhine waterfront together. I miss them both very much - Ilse would be intrigued by the book.