Talmuds and Dragons

The Inquisitor’s Tale is not a typical “Jewish kids’ book.” It does not instill Jewish identity, and most of its characters are non-Jews. Nonetheless, having stumbled upon it in my capacity as my children’s chief procurer of bedtime stories featuring magic and swordfights, I have come to view it as offering a singularly groundbreaking model, albeit a flawed one, for thinking about the possibilities of Jewish children’s literature.

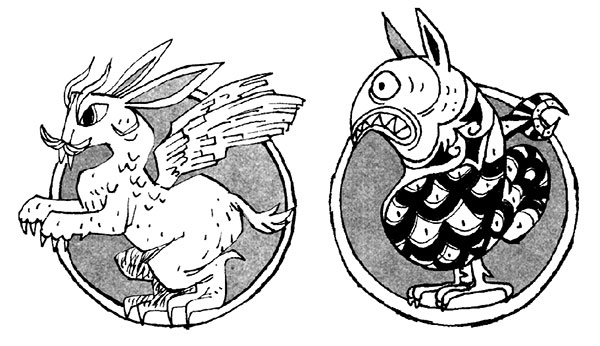

Written by Adam Gidwitz, the author of several children’s novels ranging from adaptations of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales to Star Wars spin-offs, The Inquisitor’s Tale tells the adventures of three children in 13th-century France through a cast of colorful characters gathered at an inn. Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, it weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor. It also features whimsical neomedieval marginalia by the Egyptian Canadian illustrator Hatem Aly. As I am not only a father but also a medievalist, I approached The Inquisitor’s Tale with an ambivalent mixture of excitement and trepidation. Although I love to see the distant worlds I study made available to popular audiences, and especially to children, I also wince at manipulative misrepresentations of history.

Gidwitz’s story begins with three children on the run. William, the preternaturally strong son of a crusading nobleman and an African Muslim mother, has been dumped at a monastery, where his humanism, love of theological debate, and skin color get him expelled. Jeanne, a peasant girl, has been forced to flee her village because her clairvoyant fits lead to an accusation of witchcraft. Jacob, a Jewish boy with a talent for miraculous healing, is looking for his parents, whom he hasn’t seen since his neighborhood was burned down. And let’s not forget their holy dog, whose grave became a site of popular worship and who now, having been resurrected, is wanted by the Inquisition. The children meet and, quickly overcoming their prejudices, strike up a firm friendship. Wherever the diverse trio go, they prove inspirational, leaving the reader in little doubt that they will be able to foster a harmony that their society lacks. Thus, at first glance, the story appears to be a fantasy of medieval tolerance, an edifying, anachronistic lesson on the pleasures of coexistence.

After a few chapters of this, I found myself trying to get my children to choose another bedtime story. Gidwitz’s heavy-handed moralizing about overcoming religious, racial, and sexist bigotry threatened to weigh down the story, and I found its unwitting historical mistakes grating. The ancient Maccabees are said to have fought the Romans, rather than the Greeks (let alone the Seleucids), Rashi’s scholarship is mischaracterized and shoehorned into the narrative (other rabbinic figures would have worked perfectly well), and so on. But my children wouldn’t let me stop reading. They loved Gidwitz’s humor. “Where in God’s name is my ass!?” someone exclaims as he desperately searches for his missing donkey. Then there was the chivalric chapter about “the dragon of the deadly farts”:

Jacob said, “I cured the dragon. No more deadly farts.”

“Why not?”

“See all that yellow goop down there?”

We all nodded—while trying not to actually look at it.

“That’s Époisses . . . When I first smelled the dragon, I recognized it right away. It smelled like old, digested cheese. And didn’t you say the deadly farting began when it passed through Burgundy? After attacking that inn? Cheese creates bile in some people. Makes them spend all night squatting on the dung heap. My mom is like that.”

“Does she fart fire, too?” Jeanne asked. We all laughed. Except for Georges and Robert, who actually wanted to know.

My children were also surprised and pleased to find that in a book intended for a mass audience—not one of their anodyne “Jewish books”—there was a Jewish character having Jewish experiences. This made me realize how remarkably few Jewish characters there are in books that are not expressly made and marketed for Jewish children (the exception being Holocaust literature, which, of course, is a different matter).

So, I continued reading The Inquisitor’s Tale and discovered a plot twist that I had not expected. Halfway through the book, a powerful churchman inspires the children to embark on a dangerous mission to prevent an unusual tragedy. Thousands of copies of the Talmud are about to be burned, and only the children have a hope of saving them. The heroes set out on a quest to prevent the burning. As expected, wherever they go, they convert adversaries into unlikely friends, including the king himself. Then, remarkably, Gidwitz lets them fail in their task. Their new friends do like them personally but not enough to make them rethink their prejudices more broadly, and so the Talmud is burned despite all their efforts at multicultural friendship building. In response, the children’s mission becomes not to stop evil but to sustain one another in the face of it.

The burning of the Talmud in Paris in the 1240s is, of course, a matter of historical fact. But what an odd one to choose as the centerpiece of a mass-marketed children’s book about tolerance! Medieval Ashkenazi Jews mourned the burning deeply, viscerally describing it like the death of a spouse (consider Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg’s stirring dirge, which addresses the Talmud itself, “Oh you who are burned in fire, ask how your mourners fare”), but it is difficult for most 21st-century adults, let alone children, to understand their pain. Even if one wanted to write a book for children that broached the difficult-to-convey concept of cultural loss, why focus on the Talmud, a text largely inaccessible to all but dedicated scholars, which has been marginalized within the education systems of most non-Orthodox Jews?

As counterintuitive as Gidwitz’s choice seems in theory, it turns out to be ingenious. The two non-Jewish children commit to saving the Talmud despite knowing nothing of its teachings, and it is only near the end, once their efforts have failed, that they ask what is in it. The Talmud’s survival is important to them because it is precious to their Jewish friends and to the scribes who produced it—and that is enough. Their curiosity about its contents is secondary to their commitment to each other. Moreover, their sincere participation in their Jewish friend’s grief over the destruction of his heritage prefigures their sharing in his grief over the death of his parents—and it deepens the consolation they are able to offer him. Gidwitz’s narrative thus suggests a corollary to Heinrich Heine’s famous adage about the burning of books and men: Where books are mourned, men will be mourned also.

Yes, Jacob will eventually realize that his parents must have died in the fire from which he fled. However, Gidwitz’s story is not about the horror of their death but about the living Jewish child, the support his friends offer him, and the strength he gathers from them. Together the three construct a hopeful, if sober, sense of beauty and love of life in a world that also features tragedy. The characters do not dwell on death itself. Instead, they experience Jacob’s loss in the context of the burning of the Talmud, a loss indeed, but a safely distant and nontraumatizing one for American children to contemplate. This exquisitely executed choice shields Gidwitz’s young readers (and their protective parents) from emotional overload.

What has been lost and what has been accomplished in Gidwitz’s tale? The loss is primarily located in two matters: first, the mischaracterization of the Talmud and, second, the bowdlerization of this particular episode in Christian–Jewish history. The first is a flaw that detracts from the story. The second is, I believe, a price worth paying.

Unfortunately, when Gidwitz discusses the Talmud, he offers little insight into its study as a unique intellectual venture that sustained a culture. It is valuable and hence deserving of toleration, he suggests, because it articulates the same golden rule for which Jesus also advocated. This is bad both as religious history and as ethics. Tolerating a culture because it is no different from your own is not a good test of toleration. This justification is all the more inappropriate in the context of the trial of the Talmud, which was predicated on the mutually acknowledged differences between Judaism and Christianity. Contrary to its portrayal in The Inquisitor’s Tale, the Talmud is grounded in a particularist discourse, not universalism. Jews do not make the imperialistic claim that all humanity ought to study it. The Talmud was no “Library of Alexandria”: Its burning was tragic not because humanity as a whole was hurt by this loss of knowledge—Western thought emerged unscathed—but because it injured the Jews who lived by it. But perhaps such subtlety is too much to ask of an American audience whose belief in the necessity of religious harmony outweighs their interest in religious diversity.

The liberties Gidwitz takes in reassigning responsibility for the burning of the Talmud are significant and must be considered in conjunction with the actual history. Although scholars debate the details of the burning, it clearly required considerable coordination. It began when Nicholas Donin, a disgruntled Parisian Jew, was excommunicated, then converted to Christianity and became a Franciscan friar. Donin made it his mission to denounce the Talmud, arguing that it had perverted Jews from biblical religion and impeded their conversion to Christianity. A fiery preacher, Donin spread his message widely, rousing the rabble, who burned synagogues and Jewish homes and lynched Jews. He also persuaded Pope Gregory IX to instruct authorities across Europe to impound the Talmud on the first Saturday of Lent while Jews were in synagogue. King Louis IX helped to organize an ecclesiastical trial of the Talmud at which rabbis were interrogated and the Talmud was condemned to destruction.

This history does not have the obvious makings of an American Jewish children’s story. The attempted cultural erasure of Judaism cannot be explained away as fanaticism stemming from the margins of society. It was endorsed as Christian by the highest ecclesiastical authorities, it was facilitated by a king, who was eventually canonized, and it enjoyed broad popular support. More fundamentally, many contemporary Jews are concerned that if they focus on historical Jewish suffering, they risk alienating a younger generation. Consider the planned, multimillion-dollar Jewish history museum in Tel Aviv, which is to be devoted to the celebration of Jewish accomplishments rather than tragedy and victimhood, or the suppression of tragic, or “lachrymose,” Jewish history that has for decades dominated Jewish studies in America. As Adam Teller, a critic of such approaches, has noted, it has become the norm to describe “medieval Jewish life in Germany . . . almost as a ‘convivencia’ of Jewish and Christian shared values and social experiences, the 1492 expulsion from Spain . . . as an example of Jewish migration, and the history of the Jews in late Tsarist Russia . . . largely without reference to antisemitism.”

Perhaps in deference to these considerations, Gidwitz’s story elides the most disturbing aspects of the historical record. The role of churches in impounding the books is only obliquely acknowledged, and the papal role is entirely omitted. Similarly, Gidwitz’s King Louis, perhaps because he is still revered by Catholics, largely escapes blame. He does not instigate the burning but only allows it, and he is so moved by the children that he tacitly permits them to save a handful of books. In this retelling, it is Blanche, the cartoonishly wicked queen mother, who bears ultimate responsibility for the burning (a fiction that Gidwitz himself acknowledges in his afterword). As for the mobs aroused to violence by Donin, they too are absent. In their place, Gidwitz describes Jacob’s Jewish neighborhood being burned but adds that the fire was the result of a “dare” by two “stupid boys” and that Christians were also hurt. Fanaticism, Gidwitz seems to say, is the property of unbalanced queen mothers and kids playing with matches. Neither church, state, nor society at large can be implicated.

Nonetheless, while there is much censorship and invention in Gidwitz’s retelling, there is also a poignant historical faithfulness. This is most devastatingly apparent in his description of the children’s friendship with the fictional prior of the Saint-Denis monastery. This prior fights against all forms of medieval Christian fanaticism. He rescues witches, befriends rabbis, and develops a plan to save the Talmud. He is the saving grace of Christianity, the paradigm of what a good Christian with power should be. It was this character that first struck me as taking the most liberties with history. But then, in a final twist in a book as full of miracles as the medieval literature on which it is based, we discover that this clergyman is not in fact a human product of his time but a manifestation of an archangel sent by God to change history. Thus, we learn that while Gidwitz felt at liberty to bend history to invent sometimes improbable interfaith friendships, he would not grant himself the liberty to create a human character who would anachronistically unite both Christian power and Christian compassion for persecuted minorities. Therefore, in an act that dazzlingly combines a devotion to historical fidelity and the exercise of authorial fantasy, Gidwitz intervenes with a celestial being who possesses those qualities.

The conventional wisdom of liberal American Jewish educators is that children (or at least their parents) need Jewish stories that feel relevant, speak to their own experiences, and reflect their values and goals. Too often, this attitude cuts Jewish children off from much of their heritage, which was, after all, forged in profoundly foreign environments, sometimes under terrifying pressures. It has also rendered many Jewish children’s books boring and sterile. The brilliance of The Inquisitor’s Tale lies in its use of familiar modern values as a bridge to unfamiliar historical situations. Its heroes may embody impeccable 21st-century ideals, but they inhabit a dazzlingly foreign landscape where the ideological struggles are as far removed from American life as its monasteries, taverns, and dung-heaps. Adam Gidwitz thereby shows that an obscure historical episode about a recondite text can indeed help children to thoughtfully, and even joyfully, engage with Jewish history. If it moves some older readers to do the same, so much the better.

Suggested Reading

No Jewish Narnias: A Reply

Michael Weingrad responds to readers of his essay on the dearth of Jewish fantasy literature.

East and West

In which direction should Israel orient itself?

Rashi and the Crusader: A Legend

Did the great biblical and talmudic commentator meet Godfrey of Bouilon? A fascinating excerpt from Gedaliah ibn Yahya's Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah.

Swept Up

A new documentary displays the process of conversion to Judaism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In