My Father, Milton Himmelfarb

My father, Milton Himmelfarb, who died in 2006, would have celebrated his hundredth birthday this coming weekend. He spent four decades as director of research at the American Jewish Committee. He edited the American Jewish Year Book, was a contributing editor at Commentary, and taught occasional courses at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, and Yale University. He is probably best known for a pithy characterization of the distinctive voting patterns of American Jews that goes back to his analysis of the 1968 election: Jews earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans.

My father’s interest in voting patterns was hardly dispassionate. The comparison to Episcopalians and Puerto Ricans was a response to the accusation of some on the left, “undeterred by mere fact,” that Jews had abandoned their support for liberal causes in favor of a selfish conservatism. In my father’s view, however, it was not a good thing that Jewish voting patterns were “off the graph.” Jews would have been better served by abandoning their uncritical commitment to liberalism, including their unwillingness to recognize anti-Semitism on the left, and by taking more seriously their interests as Jews.

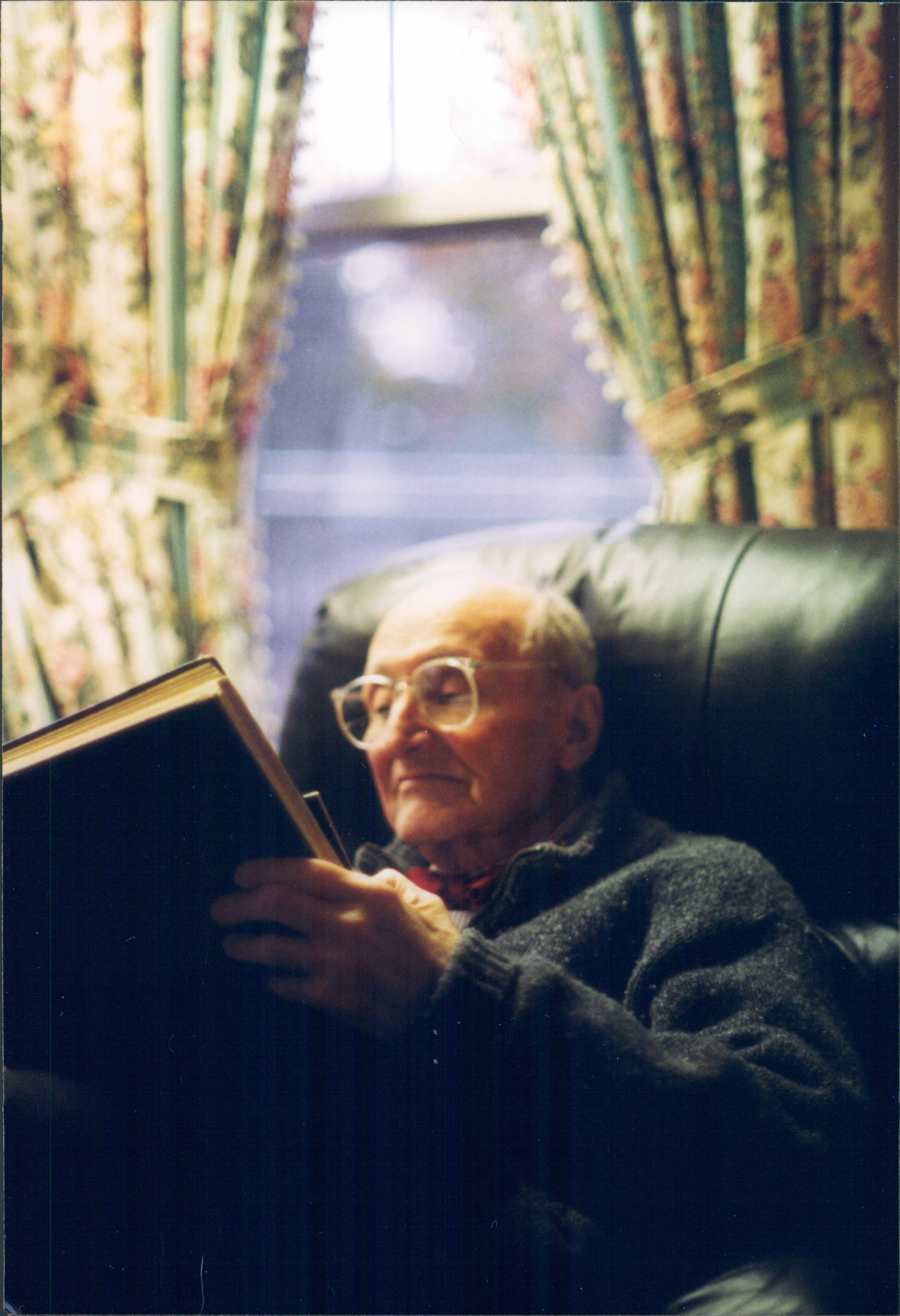

For my father, taking Jewish interests seriously meant taking Jewish tradition seriously, but his relationship to the tradition was idiosyncratically modern. His funeral took place in the Orthodox synagogue in White Plains that had been an important part of his life for more than 30 years. But, as my brother Edward pointed out in his eulogy, he had become a regular there only after resigning membership in a nearby Conservative synagogue that refused to count women in the minyan. In my father’s view, the Orthodox had a right to remain traditional on this point; Conservative Jews did not. Edward also described what was for a number of years my father’s favorite Shabbat afternoon activity: Ever interested in metrics, he would sit in a comfortable chair with the Mikra’ot gedolot (Bible with traditional commentaries) opened to the next week’s Torah portion and an electronic calculator so that he could check the gematria (the numerical values of words based on preassigned values for each Hebrew letter) in the Ba’al Ha-turim commentary. He was interested to discover the large number of instances in which the numerical value of the letters didn’t precisely add up to the theologically significant number that the commentator claimed they did. He concluded that there must have been an implicit understanding that a small deviation from the desired sum was acceptable.

Beyond the gematria, my father found the traditional commentaries on the Torah interesting, but his real passion was for modern critical Bible scholarship. He even produced some of his own: a scathing review of Mitchell Dahood’s Psalms commentary in the Anchor Bible series, in which he takes Dahood to task for an exaggerated estimation of the contribution of Ugaritic (an ancient Semitic language close to biblical Hebrew) to the understanding of the Psalms and a consequent failure to read the Psalms as Israelite literature.

My first exposure to critical Bible studies was from my father. For many years, I taught the documentary hypothesis, the theory that accounts for repetition and inconsistency in the Torah on the assumption that the text before us combines four distinct documents, as part of an undergraduate survey course at Princeton on the Hebrew Bible. (There has been significant scholarly ferment on the subject in recent decades, but I remain a supporter.) From time to time students who found their religious assumptions shaken by the documentary hypothesis would ask me if I had been similarly affected when I first learned about it. But my own experience was quite different: I had learned about it from my father in synagogue. As we sat listening to the reading of the weekly Torah portion and at greater length after the service, he would explain which sources the portion contained, how scholars had identified them, and how they fit together. I thought it was the most fascinating thing I had ever heard, and it made the Torah more wonderful in my eyes.

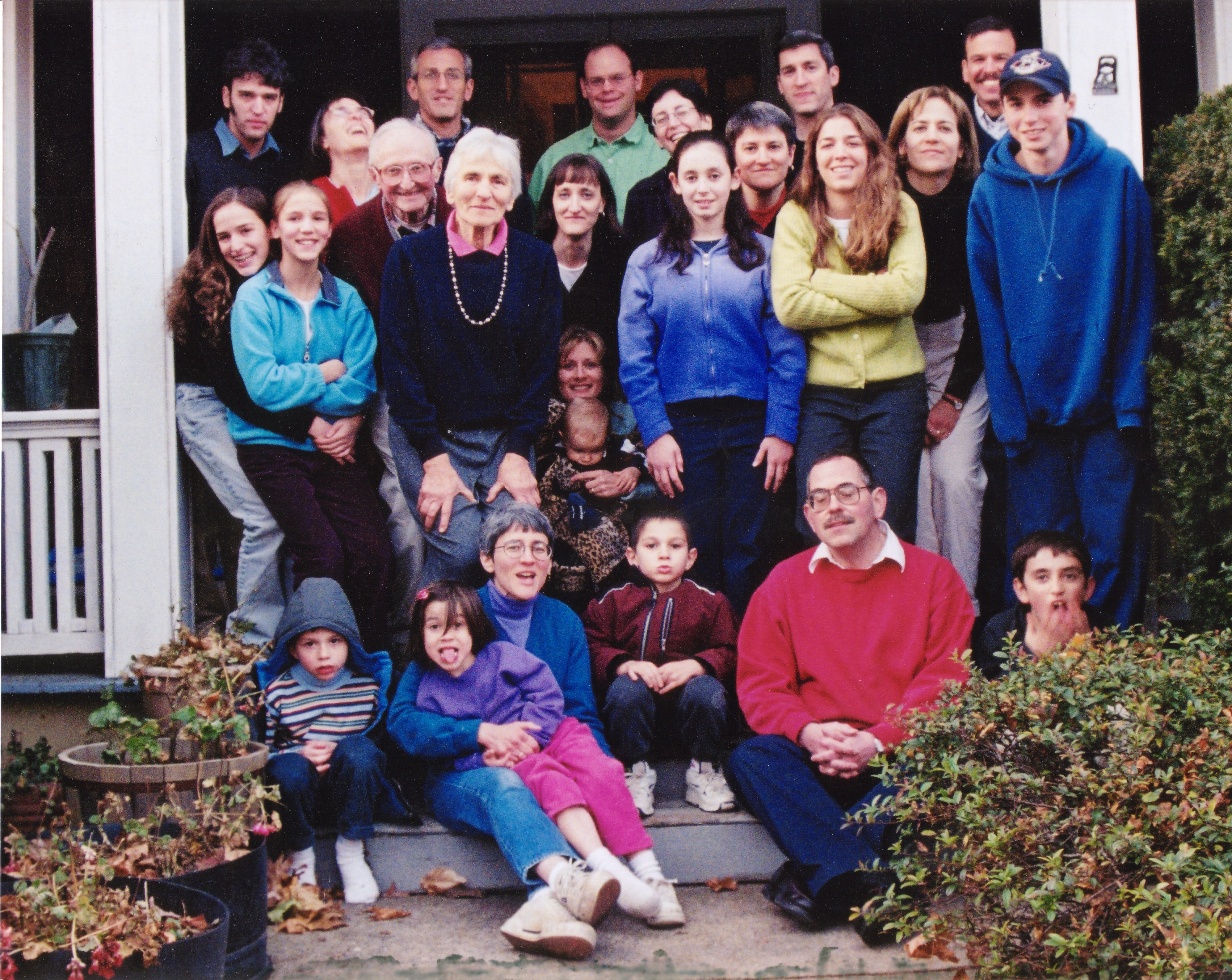

One of my father’s major preoccupations was the size of the Jewish population, or, as he titled one of his essays, “The Vanishing Jews.” I’m sorry that we will never know what he would have had to say about the remarkable statistic that, as of 2011, half of Jewish children in New York City come from haredi families. But the declining number of non-Orthodox Jews to emerge from recent studies is nothing new, and on this subject his thoughts are on record. The reasons for the mid-20th-century decline were obvious: intermarriage and an extremely low birth rate. My father argued that rabbis and Jewish communal officials were focusing on the wrong part of the problem. Instead of fighting a losing battle against intermarriage (which was still under 33 percent by 1970, very low by today’s standards), they should have encouraged American Jews to have larger families; he calculated that an average family size of 2.5 or 3 would have meant a growth in Jewish population despite the losses incurred through intermarriage. He never mentioned his seven children in making his argument, but he was delighted when my sister Naomi crocheted a kippa for him that read “av hamon,” father of a multitude, a play on God’s promise to Abraham that he would be the father of a multitude of nations (Gen. 17:4).

One obvious way to address intermarriage, my father wrote, as was often the case taking issue with the “general wisdom” of the day, would be to encourage conversion, to “get over” an aversion to proselytizing that reflects not ancient Jewish tradition but the medieval Christian prohibition of conversion to Judaism. The most likely candidates for conversion, he continued, would be the future spouses of Jews; it would hardly count as proselytizing to encourage them to become Jewish. But surely people who find the Jewish tradition rich and meaningful should not begrudge it to others. So why restrict Jewish outreach to those future spouses?

My father thought African Americans might be particularly interested in joining the Jewish people since the foundational Jewish story is so relevant to their experience in America and has already played such an important role in African American religion. Not only would it be good for African Americans—“so a Jew ought to assume”—but more black Jews would be good for the existing Jewish community, giving it a more authentic role, comparable to that of the churches, in addressing problems of race. I should add that in the same essay in which he argued that it would be good for the synagogue to have more black members, my father repeated his insistence that Jews should not make excuses for black anti-Semitism.

My father’s call for larger families went over like a lead balloon, and his suggestion about conversion was not met with enthusiasm either. While these ideas were certainly out of tune with the social realities of the time, they had the virtue of reframing the issues in a way that treats Judaism and membership in the Jewish community as inherently worthwhile and as potentially desirable to outsiders and, in so doing, treats others as potential members of the community.

If my father could be said to have had a hobby, it was reading. He was not a sports fan, and he knew almost nothing about popular culture. But in the late 1960s, when he was snowed in at a speaking engagement, his host took him to see the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine.I suspect he is the only person ever to have analyzed the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine (restored and re-released for its 50th anniversary this past summer) in relation to Matthew Arnold’s categories of Hebraism and Hellenism. Yellow, he noted, is the color of life and joy, “Hellenism” in Arnold’s terms. The Blue Meanies say no to everything; their color represents the puritanism of Arnold’s Hebraism. And while it seems unlikely that the Beatles had Arnold in mind, my father pointed to a remarkable line part way through the movie: “That’s funny, you don’t look blueish.” My father, of course, was on the side of blue, Hebraism, and saying no. The no of “thou shalt not” is the no that protects the weak from the powerful; it is the no of mercy, a distinctly Hebraic virtue.

My father went on to discuss the place of Hellenism and Hebraism in Jewish modernity: We need Hellenism, to be sure, but we need Hebraism even more. Along the way, the essay touches on the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of dry bones. My father’s generation had lived through the horrors of the 20th century: the appeasement of Hitler in the 30s, the Holocaust, and Stalin’s persecutions. But it had also seen the rise of the state of Israel, and though he rejected any attempt at theodicy, my father saw Israel’s existence as a source of profound hope. He was not impressed by Hatikva as poetry, but he embraced its transformation of the lament of the dry bones, the house of Israel, in Ezekiel’s vision. “Our hope is lost,” the prophet Ezekiel (37:11) laments. God, of course, breathes life into the dry bones, and Hatikva has us sing: “Our hope is not yet lost.” “Hope,” my father wrote elsewhere, “is a Jewish virtue.”

Milton Himmelfarb’s essays, most of which originally appeared in Commentary, are collected in two books, The Jews of Modernity (Basic Books, 1973), selected and arranged by the author, and Jews and Gentiles (Encounter Books, 2007), edited by his sister, Gertrude Himmelfarb, to honor his memory.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Kashrut and Kugel: Franz Rosenzweig’s “The Builders”

In 1923, Franz Rosenzweig wrote an open letter to Martin Buber on being bound by Jewish law in the modern age. Interestingly, he was just as concerned with minhag (custom) as halakha.

Himmelfarb, George Eliot, and the Jews

English philo-Semitism, in fiction and reality.

Journeys Without End

For some three decades Lionel and Diana Trilling shared a limelight that was not quite identical but never entirely separate.

The Court Jew Who Hated Kings

In July 1492, three months after Spain published its edict of expulsion, Abravanel sailed with tens of thousands of other refugee Jews to Italy, where the history of Sephardi Jewry and its most illustrious leader resumed on somewhat friendlier grounds.

Amy Smith

Shades of the debate over fedoras are raised by this photo.

Chava

I enjoyed this article so much because it brought back fond memories of White Plains. My family switched synagogues about the same time, more because of the politics than the actual issues. I remember your father, a"h, as being very smart and very funny - traits I am sure he passed on to his children.