Meanwhile, on a Quiet Street in Cleveland

S

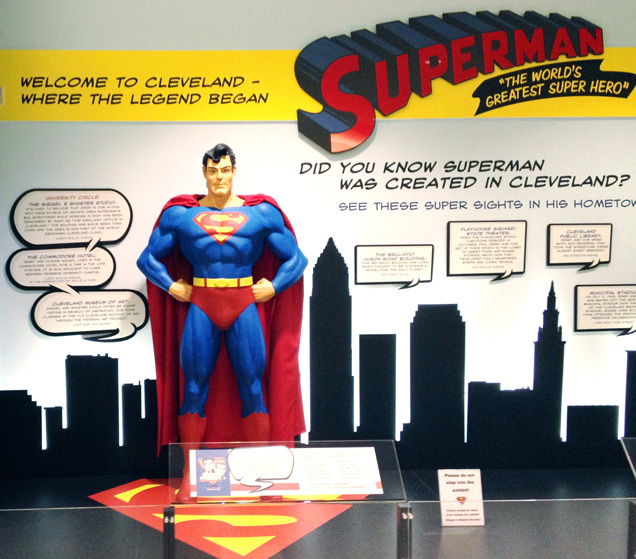

uperman was born on a hot, restless night in Cleveland, Ohio. It’s 1933 and Jerry Siegel, barely out of high school, has already been trying for years to make it as a science fiction writer, or a comic strip writer, or a writer of crime fiction, or a pulp publisher, or anything creative that could take him away from small-time retail. Dazed, he wakes up in the middle of the night with an idea. He goes to his desk and starts writing. But he’s too tired, and it’s too hot, and he goes back to bed . . . only to be compelled back to the desk! In two-hour cycles he wakes, writes, and goes back to his fitful sleep. There’s something about this idea that won’t let him go. There’s also something about the night itself that clarifies the jumble of images in his mind.

Clouds drifted past the moon. Up there was wind. If only I could fly. If only . . . and SUPERMAN was conceived, not in his entirety, but little by little . . .

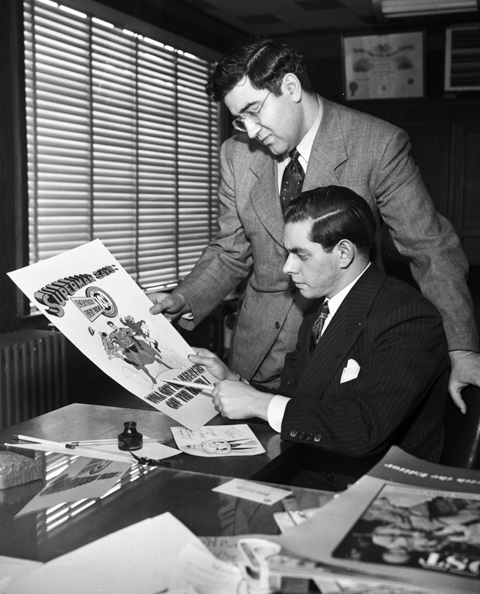

The next morning he runs to the home of Joe Shuster, his best friend and frequent collaborator. Siegel knows that the idea should be a comic, because seeing the Superman would be essential to the experience. Despite their many previous failures, Shuster believes in his friend. They start working immediately.

It’s a good story, though it is almost certainly made up. In another version, it’s 1934. Siegel had diligently worked on his Superman idea all day and awoke only to fill in the gaps. Then there is the nature of the story itself, the too-perfect elements. True, Saul Bellow once claimed that “You never have to change anything you got up in the middle of the night to write,” but few writers and artists actually compose this way, least of all Jerry Siegel. In Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman, Brad Ricca nicely describes Siegel’s story as “a magical tale about the creative process . . . After all of the failures, the one idea comes, as if from heaven, and saves him.” The truth of Siegel’s creative process is the failures, the false starts and missteps that nevertheless contained something worthwhile, interesting, maybe even new.

The actual creative breakthrough may have happened the year before, when Siegel and Shuster collaborated on an illustrated short story called “The Reign of the Super-Man.” On the surface, there’s little resemblance between “Reign” and the later Superman. The Super-Man of the early story was Bill Dunn, a Depression-era tramp who gained the ability to telepathically control others after a mad scientist secretly fed him an experimental serum. This Super-Man is a super villain! He’s used his mental powers to bring the world to the brink of war. But suddenly he gets a glimpse of a future when he won’t be able to replicate the serum and is once again destitute. The Super-Man repents in somewhat Jewish tones: “I see, now, how wrong I was. If I had worked for the good of humanity, my name would have gone down in history with a blessing—instead of a curse.”

Ricca remarks that the story contains “every single element of the superhero character that was beginning to wake,” but this understates what “Reign” actually captures. The abrupt shift in the characterization of the Super-Man marks Siegel’s real creative insight: Depression America needed a hero. Over the years, Superman has transformed into a powerful god who fights other godlike beings. In the new hit movie Man of Steel, he saves humanity from the apocalyptic Kryptonian “World Engine.” But the earliest Superman of Siegel and Shuster’s Action Comics was a social reformer: He used his super-strength to strong-arm a corrupt mine owner into investing in better safeguards and to fight the scourge of reckless driving (“The auto accident death rate of this community is one that should shame us all!” Superman correctly muses in Action #12). This was a Superman working for the good of humanity.

Yet “Reign of the Super-Man” only partially explains Superman’s origins. Siegel and Shuster’s biographers, Superman’s biographers, and comics historians are all obsessed with answering the question, “Where did the idea of a super-powered man come from?” Superman is, after all, not only the exemplary superhero, he is the first of his kind, the one whose success spawned one of the richest, most popular, most enduring, and most malleable genres in American cultural history. X-Men, The Avengers, Batman, the TV shows, the movies, the comics—none would have existed without Siegel and Shuster’s Superman.

So our biographers and historians frantically hunt for explanations. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter was a human who gained incredible jumping abilities in the lower-gravity environment of Mars. Is Superman, an alien, John Carter in reverse? Did the idea for Superman’s secret identity come from Lamont Cranston/The Shadow? Did the adventure plots come from Douglas Fairbanks movies? Did the idea for a man with super strength come from Philip Wylie’s novel Gladiator? From bodybuilding magazines like Physical Culture? From the Jewish strongman Siegmund Breitbart, who was called “Hercules” and “Superman” by the Cleveland papers? Or was Joe Shuster inspired by a different Jewish strongman, Joseph Greenstein, The Mighty Atom? It was said that Greenstein was shot between the eyes in Galveston, Texas in 1914, only for the bullet to flatten on his forehead and drop to the floor. Or maybe Superman is simply Jerry Siegel’s response to a childhood trauma.

Others have wondered if Superman can be explained by Siegel and Shuster’s Judaism. Did the idea for super-strength come from the story of Samson? Superman did threaten to tear down the pillars supporting a building in order to force a peace settlement. “A guy named Samson once had the same idea!” (Superman #2) Was super-strength a response to the insecurity that Siegel and Shuster felt as Jews in America? Or, as Harry Brod argues in Superman Is Jewish? How Comic Book Superheroes Came to Serve Truth, Justice, and the Jewish-American Way, is the combination of Superman’s super-strength and Clark’s weakness a commentary on how Jewish men were perceived? Does the way his parents saved the future savior from destruction by sending him to Earth in a small rocket make him like Moses? Others have suggested that there is something fundamentally Jewish about Kryptonite. Only the old-world past can haunt and wound the assimilated Jew.

The questions and answers simultaneously elevate and deflate Siegel and Shuster, as if the best that they could do was distill and bottle something that was already in the air. But the intensity of the questioning also shows the enduring fascination of Siegel and Shuster’s creation. It is, apparently, almost impossible to believe that Superman came through the constant writing and rewriting, drafting and redrafting, of two Jewish teenagers in Cleveland.

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster have typically Jewish American origin stories. Siegel was the youngest child of immigrants from Lithuania. His father, Michel (pronounced “Mitchell,” though he also went by Michael and Mike), owned a clothing store on Central Avenue, earning enough money to move the family to a comfortable home in Glenville, a Jewish neighborhood on the east side of Cleveland. Siegel read the comics, crime fiction, adventure, and proto-science fiction magazines such as Astounding Stories. He sent letters to the editor and tried writing his own stories. All were terrible. Shuster’s parents were also immigrants. His father, once a tailor, worked as an elevator operator at Mount Sinai Hospital. The family moved to Glenville in 1929, eventually living in a small apartment. Joe “read” the newspaper comics with his father even before he could read words. He began drawing at the age of four and began to teach himself illustration by tracing newspaper cartoons. His family encouraged his talent, and he won several contests.

Ricca’s Super Boys is at its best during Siegel and Shuster’s youth. Ricca captures the excitement of what it means for a nerdy outsider to finally meet someone similar. Ricca reads Siegel and Shuster’s earliest work in their high school newspaper, The Torch, with unusual precision and care in order to show that they were always autobiographical artists. Siegel unsubtly translated his unrequited crush on a girl named Miriam into melancholy poems and crude detective stories. It was a mode of writing he continued in Superman: Lois Lane was taken from Lois Amster, a girl Siegel admired from afar. Shuster’s sense of physical inadequacy led to an obsession with bodybuilding and strongmen. Moreover, his biggest handicap, poor eyesight, was the one Superman used to project weakness as Clark Kent: those nerdy glasses.

The most important biographical detail that inspired Superman was the death of Michel Siegel in 1932 after three men robbed his clothing store. There were reports that Siegel was shot, but it was later determined that he died of a heart attack caused by the shock. Ricca is not the first to connect Superman, the world’s ultimate crime-fighter and a man impervious to bullets, to this event. It was prominently detailed in Gerard Jones’ Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book, the best book on the creation of the comic book industry.

Ricca is unique, however, in how aggressively he seizes on this idea. Ricca finds echoes of Michel Siegel’s death throughout individual issues of Superman. In Superman #2 (1939), Superman confronts a criminal who dies suddenly of a heart attack. Superman stops to think, “Dead . . . Heart-failure! The excitement was too much for him!” To Ricca, this suggests “Siegel’s possible anger at his father for not being able to handle the ‘excitement’ of the robbery that kills him.” Later, Ricca argues that Superman’s father’s decision to send Kal-El into space rather than save himself is “perhaps a carefully constructed mythology through which the young Jerry can attempt to understand his father’s death.” While neither reading is entirely compelling (and the second is less so than the first), the underlying premise is sound. Siegel thought through comic books. Though he doesn’t quite say it, Ricca is really arguing that comic book creators draw no less from their own lives than other artists. We resist this conclusion because they write about impossibly proportioned men and women in spandex, but we shouldn’t.

Indeed, it is impossible to ignore the way that Siegel and Shuster’s frustrations with their publisher increasingly found their way into the comics. It was years from the time Siegel and Shuster created Superman until Superman’s first appearance in Action Comics #1 (1938). They extensively revised and resubmitted their Superman proposal while also developing other characters. They created Dr. Occult, Radio Squad, and Federal Men for New Fun Comics, and Slam Bradley, a tough private eye from Cleveland, for Detective Comics. Eventually, National Publications decided to publish Superman on the condition that Siegel and Shuster sold the character. For $130, Superman became National’s exclusive property. Siegel and Shuster stood to earn a percentage from later deals, such as newspaper syndication rights, but as Jones points out in Men of Tomorrow, the two never considered the creativity of modern corporate accounting.

In the lead story of Action Comics #6 (1938), “The Man Who Sold Superman,” Clark Kent meets Nick Williams, a man posing as Superman’s “personal manager.” Williams has monetized Superman: There is a Superman radio show, Superman gasoline, a Superman automobile. A nightclub siren belts the smash hit “You’re a Superman!” (“You can make my heart leap / Ten thousand feet!”) Lois sees through the scheme, and Superman stops Williams and the crook he’s hired to pretend to be Superman.

For years Siegel, Shuster, and the assistants Shuster hired to keep up with demand wrote and illustrated Superman for National. They earned a higher page rate than other freelancers, and for a time they grew rich from the Superman newspaper strip. But they never earned as much as they felt they deserved, and they received less over time. The two eventually sued National for the rights to Superman and Superboy. A court ruled that National owned Superman but not Superboy. They settled for close to $100,000 in 1948; the money almost immediately disappeared to lawyers, back taxes, and Siegel’s divorce settlement.

The ups and downs of the rest of Siegel and Shuster’s careers make for a largely depressing story: their failed comics; their legal efforts to regain their copyright; the mass public relations movement that belatedly led to Siegel and Shuster’s official recognition as the creators of Superman and an annuity from Time Warner, the current rights holder; and the continued legal struggle on behalf of Siegel and Shuster’s heirs. But it is worth highlighting two later creative achievements.

Siegel began writing Superman again in the 1950s and 1960s. Working with a number of artists, he helped create the comic’s new light-hearted, kid-centric tone and wrote some of his best Superman stories. He was even given the chance to kill Superman in 1961’s Superman #149. In the “imaginary” story (meaning, it never “happened”), Lex Luthor reforms and creates a cure for cancer. Superman testifies that Luthor should be released from prison for his work on behalf of man (shades of “Reign of the Super-Man”), and the two become friends. But it is all a charade, an elaborate scheme to catch Superman off guard! Luther traps Superman and bombards him with Kryptonite until he dies. Though it was an imaginary story, Siegel got the rare opportunity to bring a serial character full circle. He was given the right to choose what character trait would lead to Superman’s demise: his kindness or his belief in the good of humanity. (By contrast, when DC Comics decided to kill Superman in 1992 they had him lose a fight—the villain Doomsday was stronger than he was.)

Shuster’s late-aesthetic triumph is more dubious. Broke in the mid-1950s, he ended up illustrating fetish comics, drawing pictures of men and women in elaborate bondage poses, in various stages of undress. The subject may be coarse, but the art is remarkable. There is a care and surety to the line. It is unquestionably his best work in at least a decade. Even more remarkable is who he chose to draw. His men look like Clark Kent and Jimmy Olsen; his women like Lois Lane and Lana Lang. Other than the need for money, we may never know why Shuster illustrated fetish magazines. But the explanation, offered by Craig Yoe in the sumptuously produced Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-Creator Joe Shuster, that this was his retribution for mistreatment by National Publications has a certain poetic justice that makes me hope it’s true.

But, to return to Harry Brod’s question by way of Ricca, if Siegel and Shuster were autobiographical writers, does that make Superman Jewish? Arguments for a Semitic Superman are increasingly widespread. You can find them in magazine articles, in coffee table books, in Superman biographies, and in scholarly discussions of American popular culture. Yet while Superman unquestionably has Jewish elements, to argue that Superman is essentially Jewish is to misunderstand the nature of comic book narrative.

Comics are exciting, in part, because they are always moving. Comics embrace reinvention. They even birthed the beautiful term “retroactive continuity” (or “retcon”) to describe and excuse creators’ tendencies to freely change aspects of a character’s past. We can read a truly Jewish take on Superman and a completely Christological one and an atheistic sci-fi one—and sometimes find them all in the same story.

The arguments for Superman’s Jewish identity start with his Kryptonian name, Kal-El. Brod translates this as “all is God” or “all for God,” while others more convincingly read it as “voice of God.” The destruction of Krypton is sometimes alleged to have something to do with the kabbalistic creation myth of the breaking of the cosmic vessels, and Superman’s periodic homesickness a kind of survivor’s guilt. Others emphasize Superman as an Americanization narrative: The immigrant comes to America and is accepted, even becomes the symbol for America. Others see Superman’s progressive, New Deal politics as distinctively Jewish. He was a paragon of social justice, of tzedek. To others, the clearest sign that Superman is Jewish is his secret identity, Clark Kent, the weakling, the nebbish (or the man with a secret identity trying to pass as a mild-mannered WASP). Harry Brod, who once edited an anthology subtitled Explorations in Jewish Masculinity, embellishes this idea. The genius of Superman is the embodiment of the weak Jew and strong Gentile in one character:

Clark’s Jewish-seeming nerdiness and Superman’s non-Jewish-seeming hypermasculinity are two sides of the same coin, the accentuated Jewish male stereotype and its exaggerated stereotypical counterpart.

Many of these data points are compelling in isolation but less so in context. Clark Kent’s weakness is only “Jewish” when read a certain way. Jules Feiffer famously described Clark Kent as “Superman’s opinion of the rest of us.” He’s not a commentary on strength and weakness or Jew versus Gentile; he’s a hook for powerless Clark Kentish readers who wish they could reveal superpowers of their own. Likewise, few of the Jewish elements occur simultaneously. Superman was a New Deal Democrat in the late thirties, a time when Krypton was little more than a name. Kryptonite, the old world as weapon, didn’t appear in the comics until 1949.

Krypton, however, was a major part of Siegel’s second run on Superman. In Siegel’s “Superman’s Return to Krypton” in Superman #141 (1960), Superman is catapulted back in time to before Krypton exploded. He lives a life there, falling in love with a beautiful actress and growing close to his birth parents. He is ultimately forced to watch the destruction of his home world, incapable of doing anything to solve the crisis. It’s a poignant story, one that nicely illustrates that great Superman stories are about human weakness and failings as well as strength and possibilities. It can also reasonably be interpreted as a Jewish, post-Holocaust story: The old world is suddenly more meaningful to the American Jew now that it has been destroyed. But it can also be interpreted as an allegory for Siegel’s return to National and Superman. It’s exciting, but he also has no control over the character he created. He is a bystander to its fate.

Then there are the “other” Supermen. Bryan Singer’s 2006 reboot of the movie franchise, Superman Returns, gave us a second-coming story. It had a superhero who suffered for the world, and it depicted his flight as a kind of sacred weightlessness, almost an emanation of grace. By contrast, this summer’s Man of Steel crudely inserted explicit Christian references into the story: Superman is thirty-three years old, he seeks advice from a priest in front of a stained-glass window, and later falls through the heavens towards Earth in a crucifixion pose. Yet the movie also emphasized the space saga elements of the narrative. Superman is strong because he is an alien, and his flight is filmed as an explosion of kinetic energy, of the possibilities of the body. We are back to the guy who leaps tall buildings in a single bound. The movie gives us countercurrents of the sci-fi Superman and the Christian Superman. This nuance, however, was unfortunately blunted by the way the marketing emphasized Christian overtones. The studio went so far as to create a website where pastors could find sermon notes connecting Superman to Jesus.

Brod likely sees Man of Steel as an example of the continued “de-Jewification” of Superman, of the erasure of Superman’s “mischievous streak” and his transformation into a very strong saint. It’s an argument to which I’m sympathetic, but only a little. Just two years ago, writer Grant Morrison brought back Superman’s mischievousness and social consciousness in the relaunched Action Comics. Superman went after corrupt businessmen with a fervor not seen since the earliest issues of Siegel’s Action Comics version. If anything, Morrison’s secular take reminds us what a mistake it is to call Superman’s social consciousness “Jewish.” Perhaps the best way to think about the Superman story, whatever the medium, is as an unending symphony. Character traits are like musical themes waiting for variations. They are amplified or muted depending on the needs of a specific time signature.

In 1998, in a three-part story, two children of the Warsaw ghetto (who strongly resemble Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster) create stories of an “angel” in a cape and a costume with a triangular shield who comes to save them. Superman arrives, provoking the Nazi soldiers to complain to their superiors about the “Golem” they have to fight. In a sense, this is just an incorporation of the “Superman is Jewish” interpretation written into the comic itself. On the other hand, it’s completely natural. Superman is always waiting to be transformed. He is never essentially anything.

But in the beginning, it was simple. As Brad Ricca’s Super Boys reminds us, Superman was created by two Jewish teenagers who dreamed of an artistic life and who had the rare ability to continue working on an idea until it was developed, then to continue working on it until it became something larger, more poignant, more resonant, more everything. That was their superpower.

Suggested Reading

Method to Our Madness: A Response to Hillel Halkin

Hillel Halkin is the reason I moved to Israel. I read his Letters to an American Jewish Friend at sixteen, and my life trajectory was changed forever—mine and that of…

“The Cruiser” and the Jews

O’Brien himself didn’t consider his history of Zionism to be anything more than a bit of haute vulgarization, but it is much more than that. It is one of those uncommon works of political history in which a man who knows how the world works tells a great story with dazzling literary skill.

The Play’s the Thing: A Revolutionary New Haggadah

The exodus from Egyptian bondage was a good thing. What about a haggadah that is "unbound"

Exogamy Explored

Naomi Shaefer Riley brings new data and her own personal experience to the issue of intermarriage.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In